Patronage in 15th century Florence: palaces, chapels, works

In 1472, there were more woodcarvers than butchers in Florence . We know this from the Chronicle of Benedetto Dei, in which 84 stores of “woodcarvers of tarsias and ’ntagliatori” are listed for that year, compared to 70 beccai (the butchers, precisely), 66 stores of apothecaries, and then again 270 woolen mills, 83 silk factories, 54 stores of sculptors and stone carvers, and only 8 poultry and game merchants, out of a population of 70 thousand inhabitants. Painters, on the other hand, numbered about 40, but the number could be higher, since they did not have their own guild and were therefore not officially registered. These are numbers that convey the image of a city that lives for art, where one breathes art everywhere, where art is a social practice of the highest order, where it holds an importance that can be considered equal to that of politics, economics, and the military apparatus. A walk through the streets of the historic center of the Tuscan capital is enough to realize how the great patrons of the 15th century shaped the image of the city. This is true for both public patronage (an example is that of the church of Orsanmichele, decorated with the contribution of the Arts, or professional guilds), ecclesiastical patronage, and private patronage, which, moreover, is a case in itself: towards the middle of the 15th century there were in fact few Italian cities that had a republican-type structure (despite the fact that, starting in 1434, Florence was subject to the Medici cryptocracy). In many other cities, such as Ferrara, Milan, or Mantua, artistic commissions were mainly the prerogative of their respective courts. There was, of course, no shortage of private initiative, but in cities where there was a court, the wealth and splendor of private individuals failed to match that of Florentine families (the only other city comparable to Florence in the Italy of the time is Venice).

Florentine private patronage in the fifteenth century was thus closely linked not only to the economic prosperity Florence enjoyed and other situations (for example, the literacy rate, which was unparalleled in Europe: wealthy Florentines of the time invested in schools because education was considered the fundamental basis for acquiring useful skills in business), but also to the city’s political life: Florence’s republican and relatively democratic system, where political freedom prevailed, prevented (as opposed to what happened in court-ruled cities) the development of centralized cultural policies, with the result that the city’s wealthiest and most powerful families were able to use the arts as a means of asserting their prestige. Thus a situation arises in which, alongside the important public and ecclesiastical commissions (it should be remembered that the undertaking that most catalyzed the attentions of contemporaries was the building of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, Filippo Brunelleschi’s masterpiece) or mixed (for example, the Baptistery doors executed by Lorenzo Ghiberti: the management of the Baptistery was entrusted to the Arte di Calimala, or the guild of cloth merchants), private individuals became increasingly important. Florentine patronage can also develop by virtue of a religious thinking that no longer condemns wealth (the emphasis, if anything, shifts to the hard work and sacrifices required to build one’s fortune, and the virtue that needs to be exercised in order to keep one’s money and spend it well) and, conversely, in the presence of humanistic thought, embodied by figures such as those of Leonardo Bruni and Leon Battista Alberti, which linked the image of the person to the exercise of concepts such as honor and virtue, which although changeable and often elusive since they changed shape frequently even during the 15th century, were the subject of constant debate in the Florence of the time. Leonardo Bruni, for example, considers the possession of “external goods” as proof of the exercise of virtue, although, even for Bruni himself, the axiom is not always proven (“We see that men procure or preserve virtue not by external goods, but external goods by virtue, and the very happiness of life - whether it consists in enjoyment or virtue or both - belongs more to those who are furnished in the highest degree with character and intellect, but possess more than we need, but lack character and intelligence.”). Investing in a lavish palace or works of art thus becomes not only a way to flaunt one’s social status, but also to emphasize one’s virtue.

Investment in the private sector is then complemented by investment in public enterprises, especially in the construction of churches, chapels, and altars. “The main reason for the proliferation of chapels and altars in Florentine churches,” scholar Mary Hollingsworth has well explained, “was the urgent need to atone for sins especially in the acquisition of material wealth. Like charitable donations and taxes, patronage of the arts in early 15th-century Florence was primarily an obligation imposed on the wealthy. It was not the product of a well-developed aesthetic need. But if private patronage was bound by a different set of moral codes to the corporate activities of the guilds, institutional patronage did not carry with it the stigma of vainglory attached to private display.” And with a political system “designed to avoid domination by individuals,” republican Florence also turns out to be “wary of brazen displays of personal wealth.” Florence therefore knows no excesses: there is still a legal system in place to control extravagance, both in behavior and dress, and this is another reason why even today the city’s historic center appears so balanced.

This is, in essence, the context in which the most important Florentine families constructed the city’s image, both in public and in private. It is certainly arduous to try to provide complete examples of this context, since Florence is still full of attestations of that unrepeatable season, and since everywhere, in the streets, inside the palaces and in the churches there are signs of this social phenomenon that marked 15th-century Florence. To illustrate some examples, one could follow a criterion by family, thus looking for traces of what the lineages with the most availability left around the city, or by type: it is the latter criterion that we will follow here, without of course thinking of providing an exhaustive overview, and trying to identify how private Florentine patronage in the fifteenth century was essentially expressed along three directives, namely the construction of private palaces, the building of chapels and altars or even the decoration of ecclesiastical buildings, and finally the commissioning of works of art to the leading artists of the time.

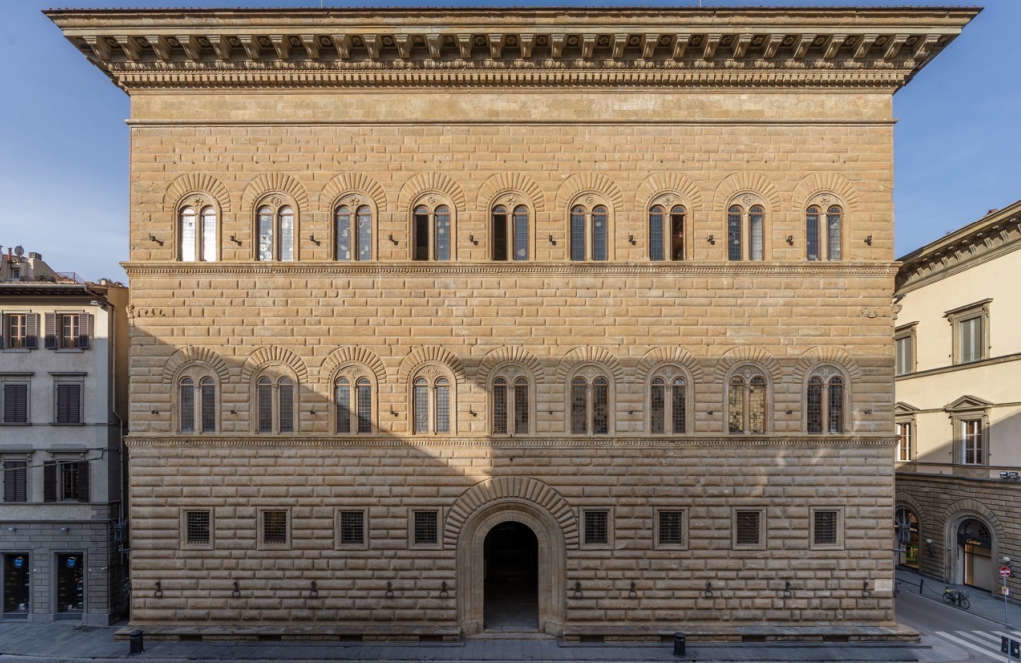

When one thinks of the palaces of 15th-century Florence, one’s mind immediately runs to the two most illustrious architects, namely Leon Battista Alberti (Genoa, 1404 - Rome, 1472) and Michelozzo (Florence, 1396 - 1472), who were responsible for designing the two palaces most exemplifying their respective artistic ideas, namely, Palazzo Rucellai, built between 1450 and 1460 on the commission of Giovanni Rucellai (Florence, 1403 - 1481), an important wool merchant who traded throughout Europe, and Palazzo Medici Riccardi, which at the time was more simply the home of the Medici (Marquis Gabriele Riccardi bought it in 1659: since then it has also been known by the name of the other great family to which the building’s history is linked), and which was commissioned from Michelozzo by Cosimo il Vecchio (Florence, 1389 - 1464), a banker, and the city’s first de facto lord (we do not know the precise date of the palace, which was built, however, between the 1540s and 1460s). Leon Battista Alberti, compared to Michelozzo, had a deeper passion for antiquity, which is why his Palazzo Rucellai appears to us to be so geometrically ordered, with regular divisions of floors both horizontally and vertically, with an appearance aimed at demonstrating that a classical order could be safely suitable not only for a Christian temple, but also for a private residence. Michelozzo, on the other hand, sought a sort of compromise between innovative and traditional elements, with the first floor characterized by heavy ashlar, the Gothic mullioned windows with two lights regulating the second floor instead (Alberti had instead abolished them), but with an inner courtyard set on a lighter, more classical loggia.

From the ideas of Alberti and Michelozzo derived the other residences of the Florentine aristocracy that can still be visited today and that have often become museum venues. Palaces played a fundamental role because they were the clearest sign of the status achieved by a family: that is why they were imposing structures, usually three-story and with an inner courtyard, with elements that could visually recall the Palazzo della Signoria, to emphasize the owner’s membership in the city’s ruling class. The best known is surely Palazzo Strozzi, designed by Giuliano da Sangallo (Florence, 1445 - 1516) or Benedetto da Maiano (Maiano, 1442 - Florence, 1497): both in fact provided a model for the client Filippo Strozzi (Florence, 1428 - 1491), a banker. The palace is exemplified on the forms of Palazzo Medici Riccardi, though larger than the latter. Next to Palazzo Strozzi can be placed Palazzo Pitti, although it underwent major transformations between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries: however, the central body of the façade still partly retains its fifteenth-century appearance, an imperious and solemn construction that recalls Roman classicism but in a way that is certainly less delicate than Palazzo Rucellai. The palace was commissioned by Luca Pitti (Florence, 1395 - 1473), a banker and rival of the Medici, although it is not clear who the architect was: perhaps Filippo Brunelleschi was responsible for the initial design, but in any case the official architect was Luca Fancelli (Settignano, c. 1430 - Florence, 1495). Then of Michelangelo-inspired design is Palazzo Antinori, perhaps designed by Giuliano da Maiano (Maiano, c. 1432 - Naples, 1490) for Giovanni di Bono Boni, also a banker, but sold as early as 1475 to the Martellis (it passed instead to the Antinoris in 1506, retaining, however, at least on the outside, its original appearance). And Palazzo Pazzi, also known as the “Palazzo della Congiura,” is also by Giuliano da Maiano, since the members of the Pazzi family responsible for the conspiracy against the Medici in 1478 resided here. Finally, Palazzo Gondi, another of the best-preserved 15th-century palaces in Florence, also deserves a mention, as it incorporates the Michellozzo idea of ashlar sloping in decreasing depth upward to emphasize the floors: it is the work of Giuliano da Sangallo (Giuliano Giamberti; Florence, 1445 - 1516) and was built between 1490 and 1498 for Giuliano di Leonardo Gondi (Florence, 1421 - 1501), an entrepreneur at the head of an important company (a leading company, we would say today) active in the production and trade of silk fabrics.

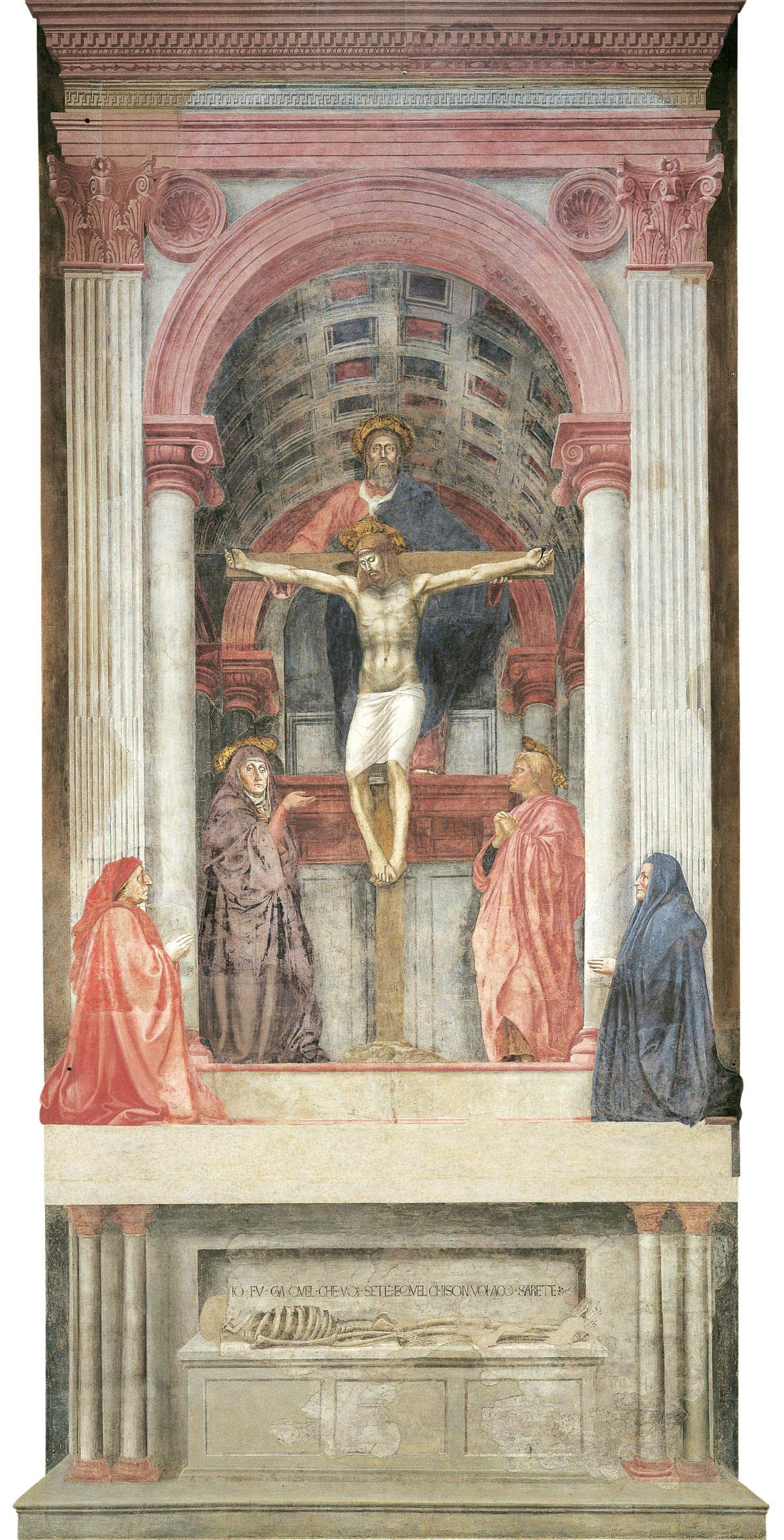

Much of the patrons’ resources, as anticipated, were invested in religious works. In fact, it was believed that financing the construction of chapels, or having them decorated, was a proper penance to atone for the sin of usury, that is, the lending of money at interest, which the Church did not allow, but which was necessary to finance the activities of many entrepreneurs of the time. Among the earliest examples of this was the Brancacci Chapel, who since the late 14th century held the juspatronage of the chapel that stands at the head of the transept of the church of Santa Maria del Carmine. It was the silk merchant Felice Brancacci (Florence, 1382 - c. 1449) who commissioned Masolino da Panicale (Panicale, 1383 - Florence, 1447), who then called the younger Masaccio (San Giovanni Valdarno, 1401 - Rome, 1428) to help him, to paint the Stories of St. Peter considered today a Renaissance masterpiece. Also Masaccio created, between 1426 and 1428, the well-known fresco with the Trinity in Santa Maria Novella, where we see depicted the two patrons, husband and wife, although we do not know their identities (this is probably a member of the Berti family and his consort, or the textile merchant Domenico Lenzi, whose burial is attested in Santa Maria Novella). It could then happen that a family secured the major chap el of even an important church: this is precisely the case in Santa Maria Novella, where the Tornabuoni family held the patronage of the major chapel. Thus, in 1485, Giovanni Tornabuoni (Florence, 1428 - 1497), a banker and one of the men most closely linked to the Medici, commissioned Domenico del Ghirlandaio (Florence, 1448 - 1494) to decorate the entire chapel with the Stories of the Virgin and the Stories of St. John the Baptist, not forgetting to have himself portrayed in a prominent position. Ghirlandaio was also employed in the decoration of the Sassetti Chapel in the nearby church of Santa Trinita between 1482 and 1485, an undertaking that contributed to the growth of the artist’s fame. Client, in this case, was Francesco Sassetti (Florence, 1421 - 1490), another banker and also a leading figure of the Medici, so much so that he had Ghirlandaio portray him, in one of the episodes of the Stories of St. Francis frescoed in the chapel, along with Lorenzo the Magnificent. The portraits (those by Ghirlandaio, who was one of the best portraitists of his time, are particularly valuable) point to a fundamental aspect of Florentine culture of the time: the real creator of the chapel was considered to be the patron rather than the artist, not least because it was the patron’s choices that directed the content and style of the decorations and not vice versa, of course. Consequently, credit for the revolutionary works that we now consider cornerstones of art history also goes to up-to-date patrons who were able to identify and recognize the most innovative artists of their time.

While the Brancacci Chapel, the Sassetti Chapel, and the Tornabuoni Chapel represent the most important decorative enterprises, on the constructive level the Old Sacristy of the basilica of San Lorenzo and the Pazzi Chapel, located next to the basilica of Santa Croce, stand out. The Old Sacristy is one of the masterpieces of Filippo Brunelleschi (Florence, 1377 - 1446), and was built between 1419 and 1428 to the design of Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici (Florence, 1360 - 1429), a banker, who commissioned the great architect a chapel that could rival the Strozzi Chapel that one of the Medici’s main rivals, the banker Palla Strozzi (Florence, 1372 - Padua, 1462), had had built in the church of Santa Trinita between 1419 and 1423, commissioning Lorenzo Ghiberti to build it. The Old Sacristy took on the appearance of an ancient sacellum, consisting of a large cubic room surmounted by an umbrella dome and open to a second smaller room (the “scarsella,” a kind of small apse), and set on careful and balanced geometric rhythms. Similar to the Old Sacristy is the Pazzi Chapel, another Brunelleschi project: it was most likely commissioned from Brunelleschi in 1429 by the banker Andrea Pazzi (Florence, 1372 - 1445), although the work took a long time. The modules recall those of the Old Sacristy, although in this case we are in the presence of a building separate from the body of the basilica: the graceful decorations in glazed terracotta by Luca della Robbia stand out here in particular, which also cover the surface of the small dome of the portico that leads into the chapel.

One could conclude with a brief overview of the main works of art resulting from patronage. The panorama is extremely vast, not least because families commissioned works from their favorite artists for the most varied reasons. Perhaps the most typical case is that of the altarpiece to decorate a chapel: one of the most illustrious examples is theAdoration of the Magi by Gentile da Fabriano (Fabriano, 1370 - Rome, 1427), which Palla Strozzi commissioned in 1423 from the artist from the Marche region for the aforementioned Strozzi Chapel in Santa Trinita: a work that has also gone down in history because it was among the most expensive of its time, as the wealthy banker paid the artist as much as 150 gold florins. To give an idea, just think that when Brunelleschi was directing the work on the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore, he received a salary of 100 gold florins a year from the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore, while Lorenzo Ghiberti, who supervised the work along with Brunelleschi from 1420, the year both were appointed, until 1425, received three florins a month. In essence, the work cost Palla Strozzi the equivalent of a year and a half’s salary of the greatest architect of the time. Very significant is another work intended for a church, that of Sant’Egidio: it is the Portinari Triptych, a masterpiece by Hugo van der Goes (Ghent, c. 1440 - Auderghem, 1482) that the commissioner, the banker Tommaso Portinari (Florence, 1424 - 1501), director of the Bruges branch of the Banco mediceo (i.e., the Medici bank), had commissioned from the Flemish painter with the specific idea of bringing the work to Florence (where it was actually placed, in the spring of 1483, inside the church that was to house it: today it is in the Uffizi instead). The work is also of great interest for the history of the culture of the time, because it demonstrates the refined, up-to-date and open taste of its patron, one of the few Florentines who, for a work for public use, preferred to turn to a non-Tuscan and even non-Italian artist.

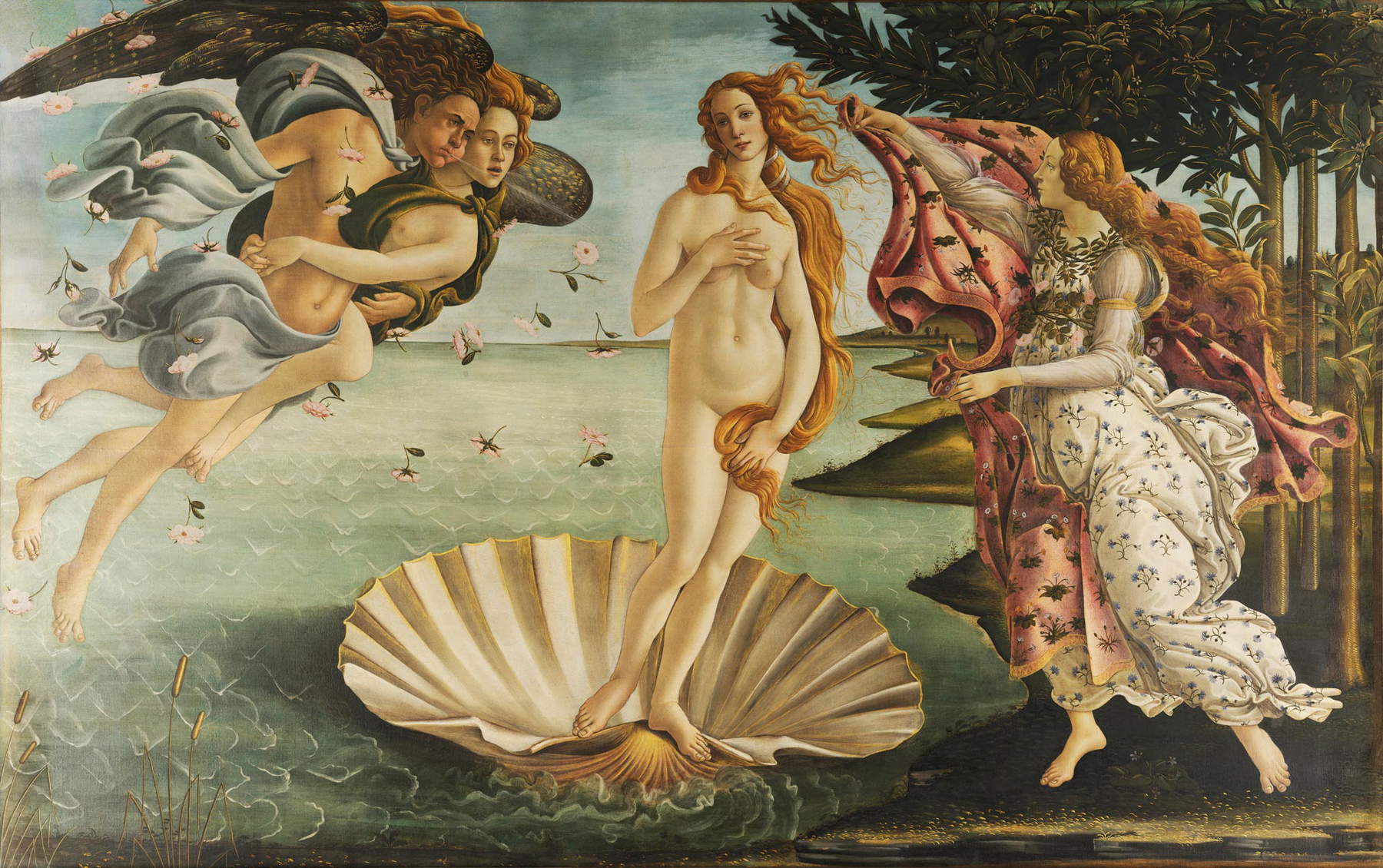

At other times, the works were intended to decorate a private residence, and the subjects could be the most diverse. Staying in Florence, it is possible to see in the Uffizi one of the panels of the Battle of San Romano by Paolo Uccello (Paolo di Dono; Pratovecchio, 1397 - Florence, 1475), likely commissioned by Lionardo di Bartolomeo Bartolini Salimbeni, a wool merchant, for the decoration of the “Camera grande” of the family palace located near Santa Trinita. And since Leonardo Bartolini Salimbeni served in military service in Florence’s campaigns against Milan and Siena, it is possible that he wanted to celebrate the event with a cycle of three works evoking one of the clashes, the battle fought at San Romano on June 2, 1432 between the Florentines and the Sienese, in which he must have participated. A work, then, with a clear celebratory intent. Works of art intended for private use could then also take on markedly educational purposes: this is the case with the Primavera and Venus by Sandro Botticelli (Alessandro Filipepi; Florence, 1445 - 1510), commissioned by the Medici. In all likelihood, the great Florentine painter’s Neo-Platonic images were intended to inspire the exercise of virtue in Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, known as the Popolano (Florence, 1463 - 1503), a cousin of the Magnifico and a member of a cadet branch of the family).

Then there are special cases such as Verrocchio ’s David (Florence, 1435 - Venice, 1488), which was commissioned from the great sculptor by Lorenzo the Magnificent (Florence, 1449 - 1492) and his brother Giuliano de’ Medici (Florence, 1453 - 1478), who then, in 1476, for the price of 150 florins, sold the bronze to the administration of the Florentine Republic with a view to placing the work at the entrance to the Sala dei Gigli in the Palazzo Vecchio: the biblical hero David was indeed seen as a symbol of political freedom. There is no shortage of bust-portraits, although these are not so frequent cases: the most famous is surely the one portraying Piero di Cosimo de’ Medici (Florence, 1416 - 1469), son of Cosimo the Elder and father of Lorenzo the Magnificent, made by Mino da Fiesole (Poppi, 1429 - Florence, 1484) between 1453 and 1454. It is also the first known Renaissance bust-portrait deliberately inspired by busts of Roman classicism. The revival of classicism had, moreover, led several patrons to commission artists to make works that directly recall antiquity, for example, portraits of the heroes of antiquity that adorned their private residences: this is the case, for example, of Desiderio da Settignano’s Olimpia (Settignano, c. 1430 - Florence, 1464), one of the best heroic profiles of the Renaissance, now preserved in Spain (we do not know the commissioner). And also with celebratory tones is the famous cycle of Andrea del Castagno’s Illustrious Men (Castagno d’Andrea, 1421 - Florence, 1457), which decorated the Villa Carducci in Legnaia: there are also effigies of the three great modern poets (Dante, Petrarch and Boccaccio).

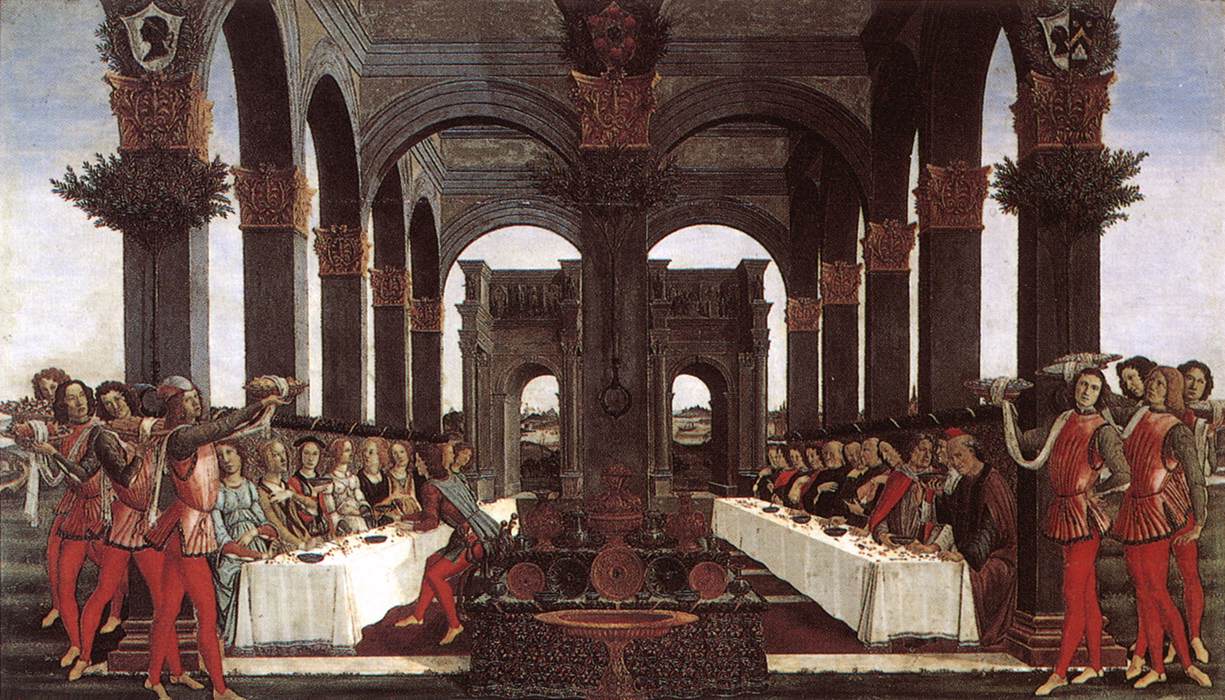

Again, the works could also be commissioned to celebrate an anniversary or holiday: perhaps the best-known example is the series of four panels with the Stories of Nastagio degli Onesti that Sandro Botticelli probably painted for Lorenzo the Magnificent, who requested the works as a gift to Giannozzo Pucci on the occasion of his marriage to Lucrezia Bini. Most of those works are now preserved in museums, but there is still something left instead, despite centuries having passed, in the availability of the descendants of the commissioners, or recipients: precisely one of the panels of the Stories of Nastagio degli Onesti is still in what was once the recipient’s family palace, Palazzo Pucci in Florence (although for some time he moved away from it). The vast majority of the works, however, have changed meaning: from expressions of economic, financial and political power they have now become witnesses to the history that produced them.

Essential Bibliography

- Maria DePrano, Art Patronage, Family and gender in Renaissance Florence, Cambridge University Press, 2018

- Michael Wyatt, The Cambridge Companion to the Italian Renaissance, Cambridge University Press, 2014

- Paul D. McLean, The Art of Network. Strategic interaction and patronage in Renaissance Florence, Duke University Press, 2007

- Sergio Tognetti, The Affairs of Messer Palla Strozzi (and his father Nofri). Entrepreneurship and Patronage in Early Renaissance Florence, in Annals of the History of Florence, IV (2009), pp. 7-88

- Mary Hollingsworth, Patronage in Renaissance Italy, John Murray Publishers, 1974

- D.S. Chambers, Patrons and Artists in the Italian Renaissance, University of South Carolina Press, 1971

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.