Perugino, Italy's best master. Here's what the Perugia exhibition looks like

In the eyes of Agostino Chigi, Perugino was the “best master in Italy.” He wrote this in a letter sent to his father Mariano on November 7, 1500, discussing the possibility of commissioning him to paint an altarpiece for the family altar in the church of Sant’Agostino in Siena. The artist would later actually receive the commission, in 1502: the work, delivered four years later, is the Chigi Altarpiece that is still there today. And “best master of Italy” is the phrase the National Gallery of Umbria has chosen for the title of the exhibition(The Best Master of Italy. Perugino in his time) set up in the large Sala Podiani for the 500th anniversary of the death of the artist, who died in 1523 while at work in the Oratory of the Annunziata in Fontignano. The exhibition, curated by Marco Pierini and Veruska Picchiarelli, has the stated goal of “recovering the right perspective, to return Perugino to the role that his audience and his era had assigned him.” And in order to feel the need for this recovery, it is necessary to move away for a moment from the encomiastic tones of Agostino Chigi to see how Perugino has been treated by critics.

Obviously the starting point can be none other than Giorgio Vasari. And it certainly cannot be said that the Aretine historiographer used too many regards toward Perugino in his Lives. One should not be misled by the praise that Vasari occasionally reserves for his masterpieces, as when he says that the frescoes of the Collegio del Cambio are a “beautiful and praised” work and “held in high esteem”: that of Perugino is a portrait “as vivid as it is disliked,” as Antonio Paolucci had defined it. Read the incipit, meanwhile: Perugino is presented as a poor artist, who painted first out of necessity and then out of terror of becoming poor again, and who therefore would never have bothered to suffer cold, hunger, discomfort, or fatigue. Beyond the fact that the Vasarian account is probably untrue (from other sources we know that Pietro Vannucci came instead from a wealthy family with some possessions in Castel della Pieve, today’s Città della Pieve, his birthplace), the Perugino of the Vasarian account comes across as a painter who “did things to earn money, which he would not perhaps have looked at, if he had had to support himself.” An unflattering description, if you will, especially considering that in the lives of other artists Vasari does not spare praise already at the opening. The worst of it, however, is concentrated in the final part, in which Vasari examines the extreme phase of Perugino’s career, writing that “Pietro had worked so much and so much always abounded in him to work, that he often put the same things to work well; et era talmente la dottrina dell’arte sua ridotta a maniera, ch’e’ fare a tutte le figure un’aria medesima.” Not only that: seeing his fame tarnished by Michelangelo, Perugino “sought much with biting words, to offend those who worked. And for this he deserved, besides some ugliness done to him by the artisans, that Michele Agnolo in public told him that he was clumsy in art.”

Vasari’s Perugino is, in short, an artist capable of some sharp but money-conscious, repetitive in his later years, and even insolent. And in the Lives, where although his pupils are named, the real import of his language is nevertheless overlooked. Hence originates that “alternating-current critical tracing,” as Veruska Picchiarelli defines it in the exhibition catalog, which would accompany Perugino’s fortunes from that time on: a tracing “from which he emerges at times as little more than a clumsy craftsman, at times as an epic innovator.” The appreciation of his contemporaries is not matched by the severity of Vasari’s judgment, which would have contributed to decisive influence on the fortunes of Perugino, long considered (with a few glowing exceptions) mostly as an artist of local importance, as one of Verrocchio’s pupils, or at best as Raphael’s master. Well: the exhibition starts precisely from here, bearing in mind the results acquired with the conference of 2000 and the great exhibition of 2004, moments through which a complete and precise reconstruction of the story of Pietro Vannucci has begun. There are therefore two directives along which the Perugia exhibition is oriented, summarized with effectiveness and vivid immediacy by the title. “Best Master” and “Italy.” on the one hand, the reconstruction of the first two decades of Perugino’s activity (in fact, the exhibition ends on the first foreshortening of the sixteenth century, with two works such as the Marriage of the Virgin on loan from the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Caen, which returns to Perugia for the first time since the Napoleonic spoliations, and the Struggle between Love and Chastity from the Louvre), that is, the period in which the artist laid the foundations of his success, and on the other hand an examination of the spread of Peruginism, the affirmation of a language that would be spoken, of course with all the local inflections of the case, from the north to the south of the peninsula. It was the first time since Giotto that an artist was able to impose his own figure in almost all of Italy. And it is above all this dimension of Perugino that is intended to emerge from the exhibition.

The opening of the exhibition attempts to reconstruct the artist’s beginnings, recognizing that we are moving on complicated ground. A whirlwind start, with the display of the problematic eight panels from what was once called the “1473 Bottega.” these are the Stories of St. Bernardino, for the occasion moved from the Perugino Room of the National Gallery, where they are usually exhibited, to the corridor that opens the exhibition in Sala Podiani, and for which Perugino authorship is reaffirmed, at least as far as the overall direction and execution of two panels are concerned, those with St. Bernardino healing the daughter of Giovanni Antonio da Rieti from an ulcer and St. Bernardino restoring sight to a blind man. The diversity of styles and discontinuous quality (there are also two panels, the stiffest ones in the series, that have yet to find an attribution) has led to the identification for these panels of as many as four different authors, at least according to what the exhibition reconstructs: Perugino, Pinturicchio, perhaps Sante di Apollonio del Celandro, and as anticipated an unknown still in search of a name. The opening with the eight panels, which, if due to Perugino, are the work of a young man who had just finished his training in Florence and had just returned to Perugia, is functional in giving the visitor an account of that “early and burning Verrocchio flare-up” (so Emanuele Zappasodi in the catalog) that invested the Umbrian capital in the 1570s, precisely as a result of the innovations that Pietro Vannucci brought back from Florence. An important renewal whose origins are immediately reconstructed: that is to say, the exhibition returns to the subject of Perugino’s training, and it does so with a juxtaposition (which is proposed again a few years after the great exhibition on Verrocchio at Palazzo Strozzi) between two Madonnas of the “Verrocchio area,” the one at the Jacquemart-André in Paris given to Perugino and the one in Berlin traditionally attributed to Verrocchio. These are much-discussed paintings: in Finestre sull’Arte, for example, Gigetta Dalli Regoli gave the Berlin work precisely to Perugino, albeit placing a question mark beside the Umbrian painter’s name, and it was also attributed to Perugino in the catalog of the major 2004 exhibition. Instead, Zappasodi reads in it the products of two different authors, identifying in the Berlin panel a work of “supreme and artificial elegance” and in the Paris one a painting that reinterprets the other “in a more standoffish, ironic and charged tone” and reveals an “exuberant, almost irreverent physicality, foreign to Verrocchio’s sophisticated formalism.” A sign, according to the scholar, that we are dealing with two different authors.

However one feels about these specific panels, there is no doubt that Perugino’s beginnings are under the banner of adherence to Verrocchio’s syntax and grammar: compositional elegance, movement evident especially in the drapery, vigorous drawing, solid and almost statuesque volumetries, and a strong luministic sensibility. These are characteristics shared by Perugino’s contemporaries who were in Verrocchio’s workshop in that period, between the late 1560s and early 1570s: representing them in the exhibition are Ghirlandaio and Francesco Botticini, as well as the Pala Macinghi, freshly restored. And they are also found in a youthful apex such as the Pietà del Farneto, a canvas restored for the occasion, and which in the exhibition enjoys a new reading aimed at giving the work a prominent place in the path of the young Perugino: his dependence on the ways of Verrocchio is reaffirmed, but the disruptive role he had on the Umbrian school is also emphasized, with the attempt to update a master like Giovanni Boccati, who attempted a Pietà (now in the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria) looking at his very young colleague.

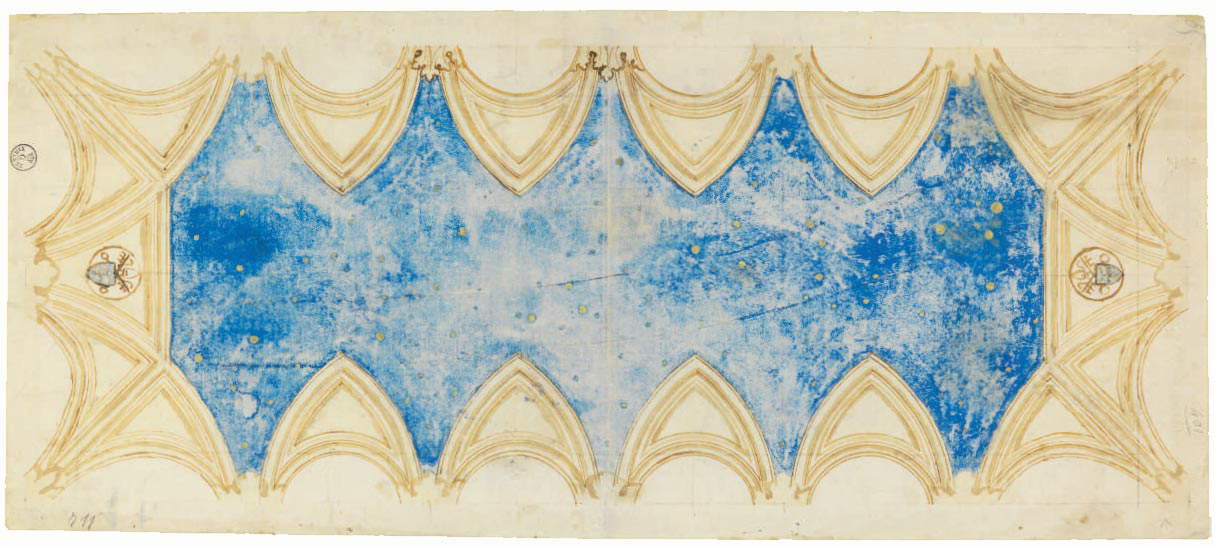

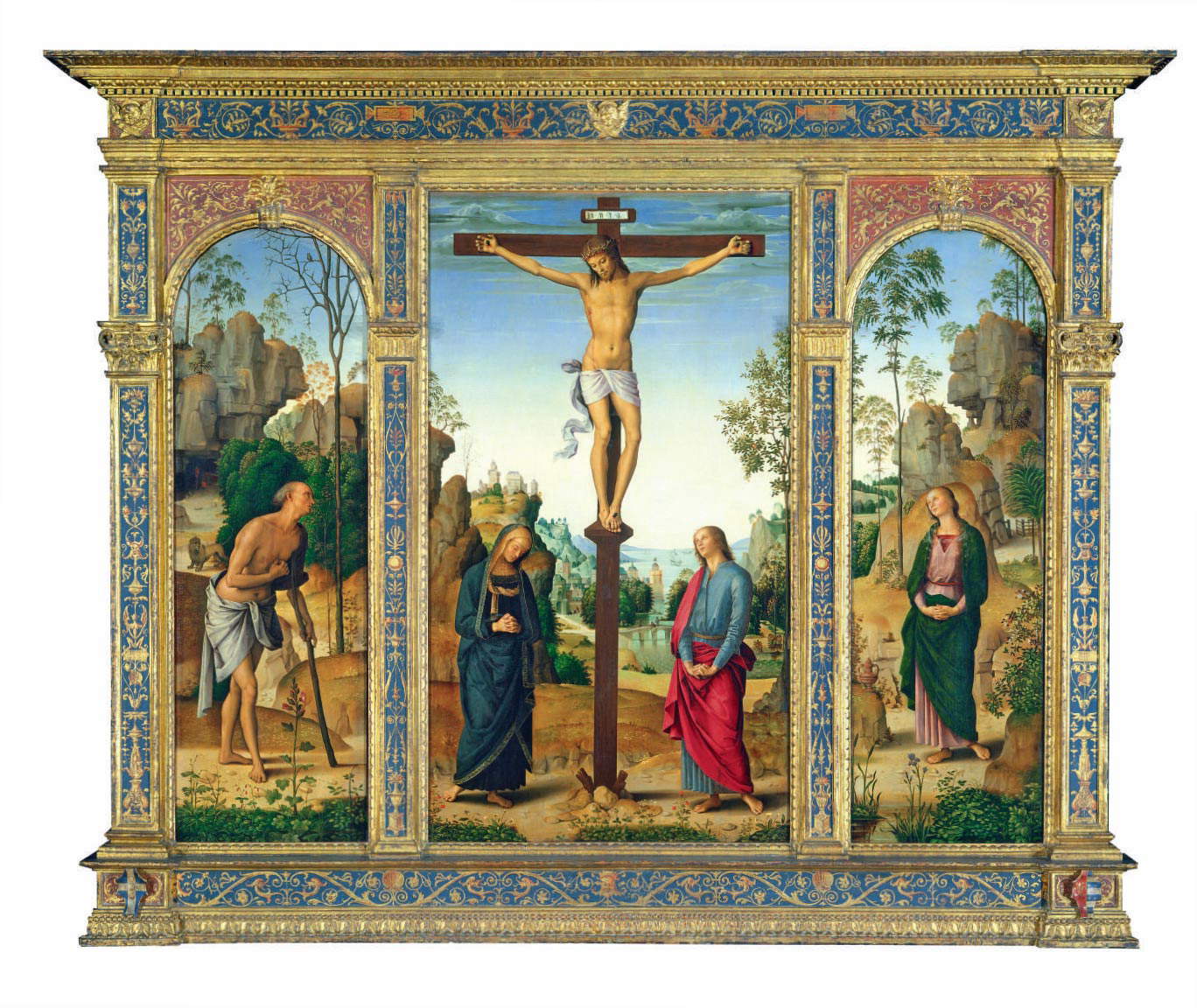

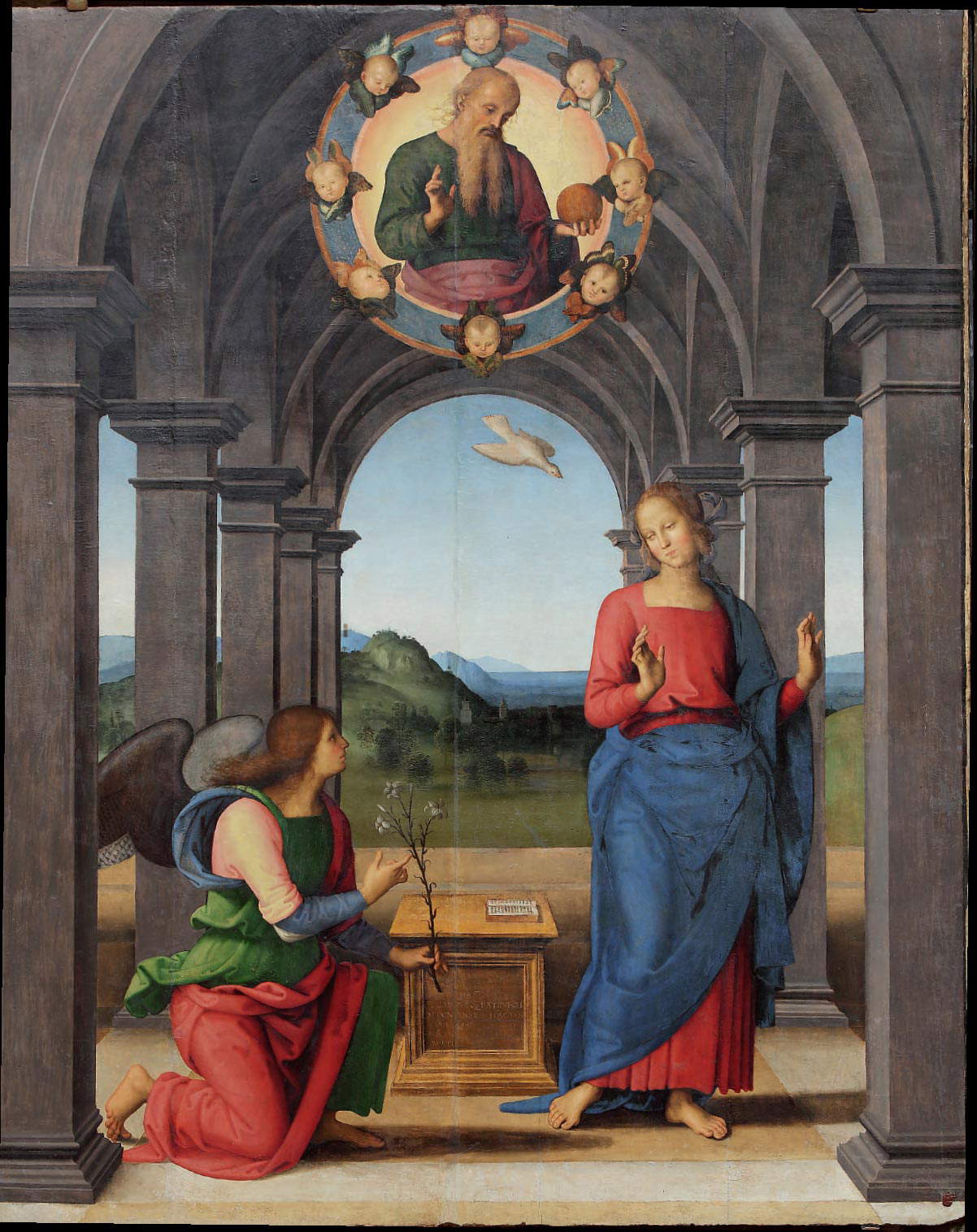

The second part of the first room delves precisely into the Umbrian masters active in Perugia at the time Pietro Vannucci returned from Florence: theAdoration of the Magi by the melancholy and delicate Benedetto Bonfigli and the Triptych of the Confraternity of Justice by the more open and impetuous Bartolomeo Caporali (the work was executed in collaboration with Sante di Apollonio del Celandro) follow one another, established artists who could be called ’transitional’, since they had no preclusions about the novelties that were coming from Tuscany, but were nonetheless reluctant to abandon traditional gold backgrounds. One can therefore imagine the upheaval that a panel such as Perugino’sAdoration of the Magi, an early masterpiece with which Vannucci shows that he had already broken away from the strict adherence to Verrocchio’s modes to seek a personal path, capable of taking into account the sweetness of the Umbrians, the solid geometrism of Piero della Francesca, and Leonardo’s sfumato (indeed: Zappasodi has proposed identifying precise references of the draperies of theAdoration in some of Leonardo da Vinci’s studies), the minuteness of the Flemish. TheAdoration also closes the first room and introduces the second, which deals with the Perugino of the 1480s, a period in which the affirmation of the painter from Città della Pieve began: it was 1478 when he was called by Sixtus IV to fresco the chapel of the Conception in St. Peter’s, a decoration that was lost but must have been much appreciated, to the point that within a few months Perugino was entrusted with directing the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel, completed in 1482. For Perugino it was a “quantum leap,” as Andrea De Marchi titles in his catalog essay on the transition from works in Perugia to thoseproduced in Rome, and to evoke the Roman enterprise the exhibition deploys a study for the decoration of the vault of the Sistine Chapel, namely Piermatteo d’Amelia’s starry sky later removed to make room for the scenes that Michelangelo would paint just under thirty years later, and a study by Sandro Botticelli, another artist employed by Sixtus IV. For Perugino it was the moment of consecration, which resulted in a season of intense work, represented in the exhibition by an exceptional loan such as the Galitzin Triptych arriving from the National Gallery in Washington: it is the work that marks perhaps Perugino’s closest approach to Flemish painting, so much so that there has been talk of a possible dependence on Hugo van der Goes’s Portinari Triptych and the works of Hans Memling that had begun to circulate in Italy precisely in the 1570s. Unusually elongated figures, a terse and diffuse luminosity, an unusual attention to detail: all elements that are not found in other Perugian paintings (so much so that in the past the Galitzin Triptych was ascribed to the young Raphael) and that make this work a hapax in the itinerary of the Umbrian painter. The work is displayed alongside Luca Signorelli’s St. Onofrio Altarpiece, which came on loan from Perugia’s Museo del Capitolo (which obtained Perugino’s Martinelli Altarpiece in exchange from the National Gallery), to demonstrate the closeness between the Cortona artist and Pietro Vannucci in the 1980s: the two worked together in the Sistine Chapel, and their proximity is evident even to a distracted eye simply by noting the poses of Signorelli’s Saint Onofrio and that of the Saint Jerome in the Galitzin Triptych, derived from the same model. At the close of the second room, the FanoAnnunciation, executed between 1489 and 1495, initiates the audience into the more delicate modes of the 1490s, to certain innovative solutions (such as the idea of setting the scenes under foreshortened loggias in central perspective), in short to perhaps Perugino’s most famous.

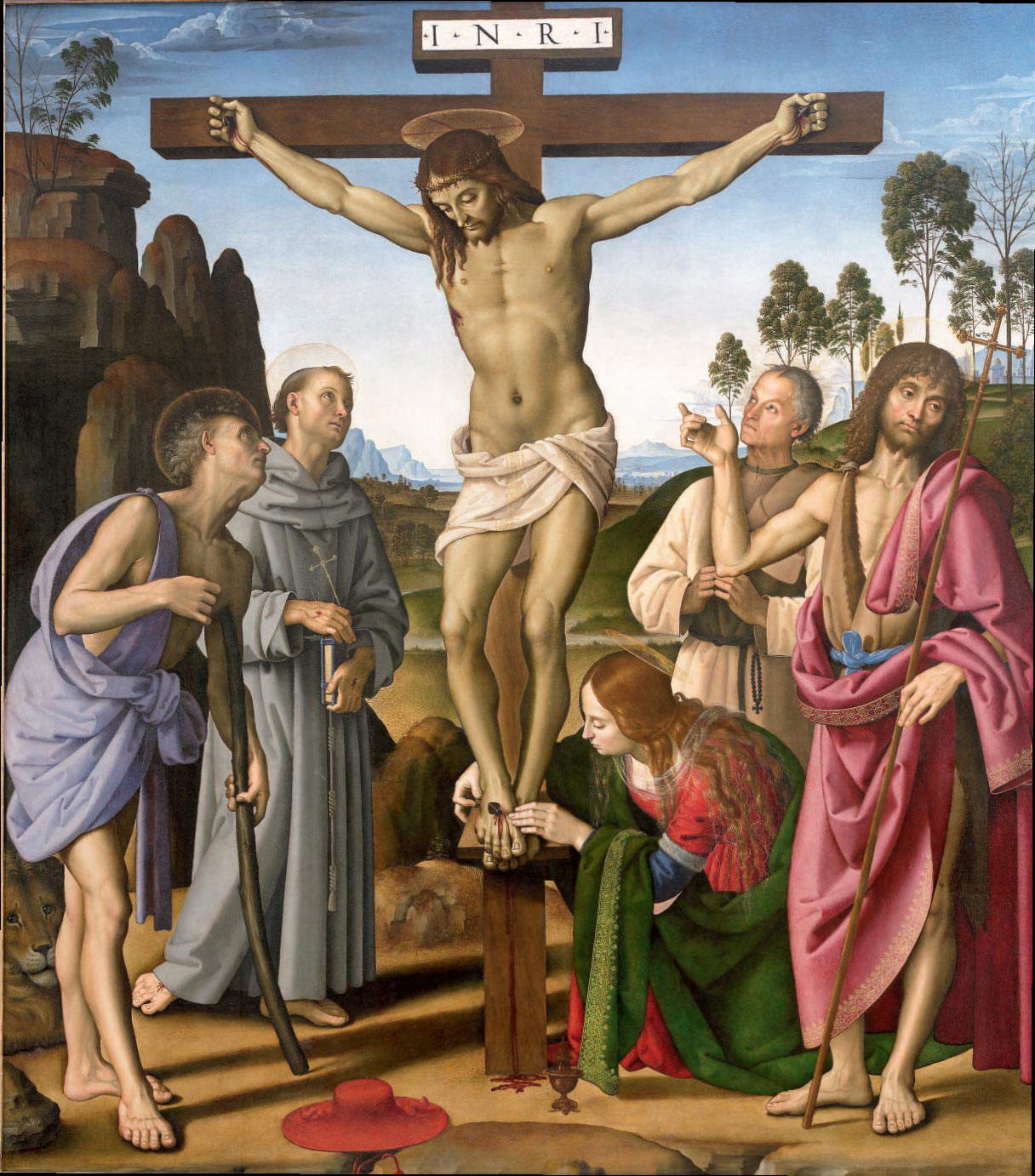

The turning point in Perugino’s career is identified by Veruska Picchiarelli in the Pietà of San Giusto alle Mura, now in the Uffizi, described as a “work of poignant beauty, highly refined execution, and thoughtful invention.” The watershed characters, which would be the basis of Perugino’s fortune and make him a much sought-after artist, are to be found in the delicacy of the figures, the extreme compositional harmony, the somewhat dreamy expressions of the characters, the fineness of the drawing, the clarity of the light, and the settings: in this case, it is perhaps Perugino’s first work in which the characters find space in a foreshortened loggia in central perspective. Anticipated by Christ Crucified among Saints (which in the catalog appears in the third section, but in the exhibition is displayed next to Signorelli’s St. Onofrio Altarpiece: a comparison nonetheless pertinent for the vigor of certain figures and, again, for the pose of St. Jerome still drawn from the same model), the Pietà is displayed alongside theOration in the Garden, which like the Pietà and Christ Crucified comes from the convent of San Giusto alle Mura and is preserved in the Uffizi. Perugino, in this section of the exhibition, is framed in the period when his success began, which would take his works beyond Umbria and beyond Florence: as evidence of how much he was in demand, the exhibition displays two important works that straddle the 1490s and the beginning of the new century, namely the Scarani Altarpiece, intended for the chapel of the family of the same name in the church of San Giovanni in Monte in Bologna, and the Polyptych of the Certosa di Pavia, whose panels, now divided between the Certosa di Pavia and the National Gallery in London, have been exceptionally brought together. In works such as these, Perugino developed formulas that he would later retrace throughout his career: characters arranged in strict symmetry, ecstatic expressions, expansive landscapes that often open onto lake views (Lake Trasimeno is perhaps the most recurring presence in Perugino’s paintings), mystical apparitions within almonds (such as the Virgin and Child in the Scarani Alt arpiece and the Padreterno in the Polyptych of the Certosa di Pavia). The comparison with Gaudenzio Ferrari’s Padreterno from the Galleria Sabauda in Turin is interesting: the Piedmontese painter clearly echoes that of the Polyptych of the Carthusian Monastery in Pavia, and the exhibition thus opens in anticipation the discourse on the spread of the inventions and language of Perugino, to whom the penultimate room is dedicated.

Alongside these works, two important “Perugian” works are also on display, such as the delightful Annunciation Ranieri, first exhibited in 1907 and painted by Pietro Vannucci for a private client, and the cymatium of the Pala dei Decemviri, an important public commission since it was destined for the chapel of the Priors of Perugia. There is no altarpiece, which is now in the Pinacoteca Vaticana, but the cymatium allows us to see a Perugino measuring himself against Venetian models (in particular, as Andrea De Marchi has found, the artist looks to Marco Zoppo and Giovanni Bellini): the artist stayed in Venice between 1494 and 1495, and the theme of the relationship between the artist and Venice is still to be explored since studies on the subject are very recent. We find ourselves before a painter who is now mature, an artist who has now established himself not only in his Perugia but also outside it, a painter at his apotheosis, “fully centered,” as Veruska Picchiarelli defines him, a Perugino who “has over the years absorbed everything that could interest him and has definitively elaborated his poetics. He established the ultimate foundations of his art” and who “carries this vision forward with a confidence entirely in keeping with that ’porphyry brain’ that Vasari attributes to him. Retracing one’s steps to reach a new goal. This is the ultimate greatness of Perugino.”

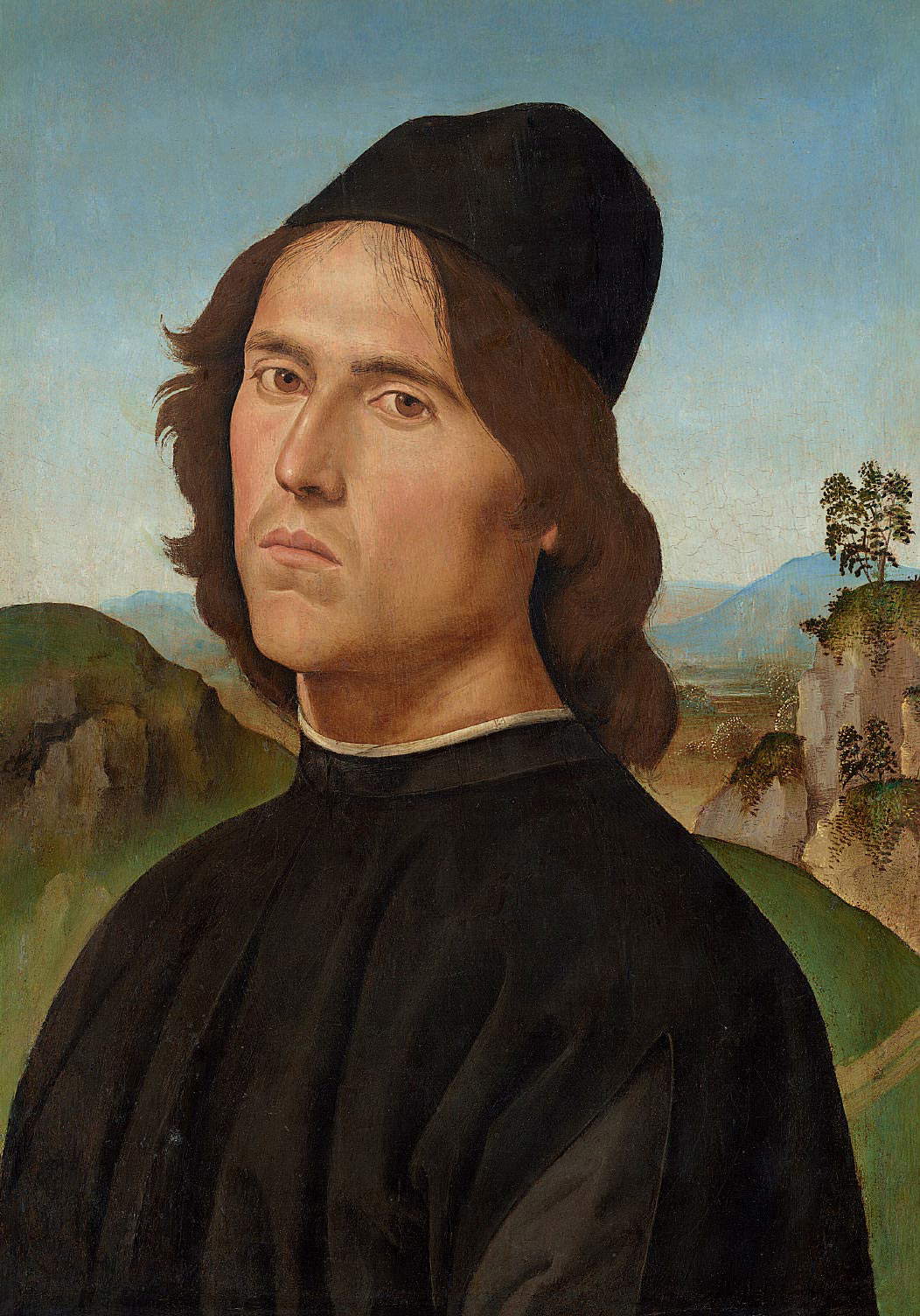

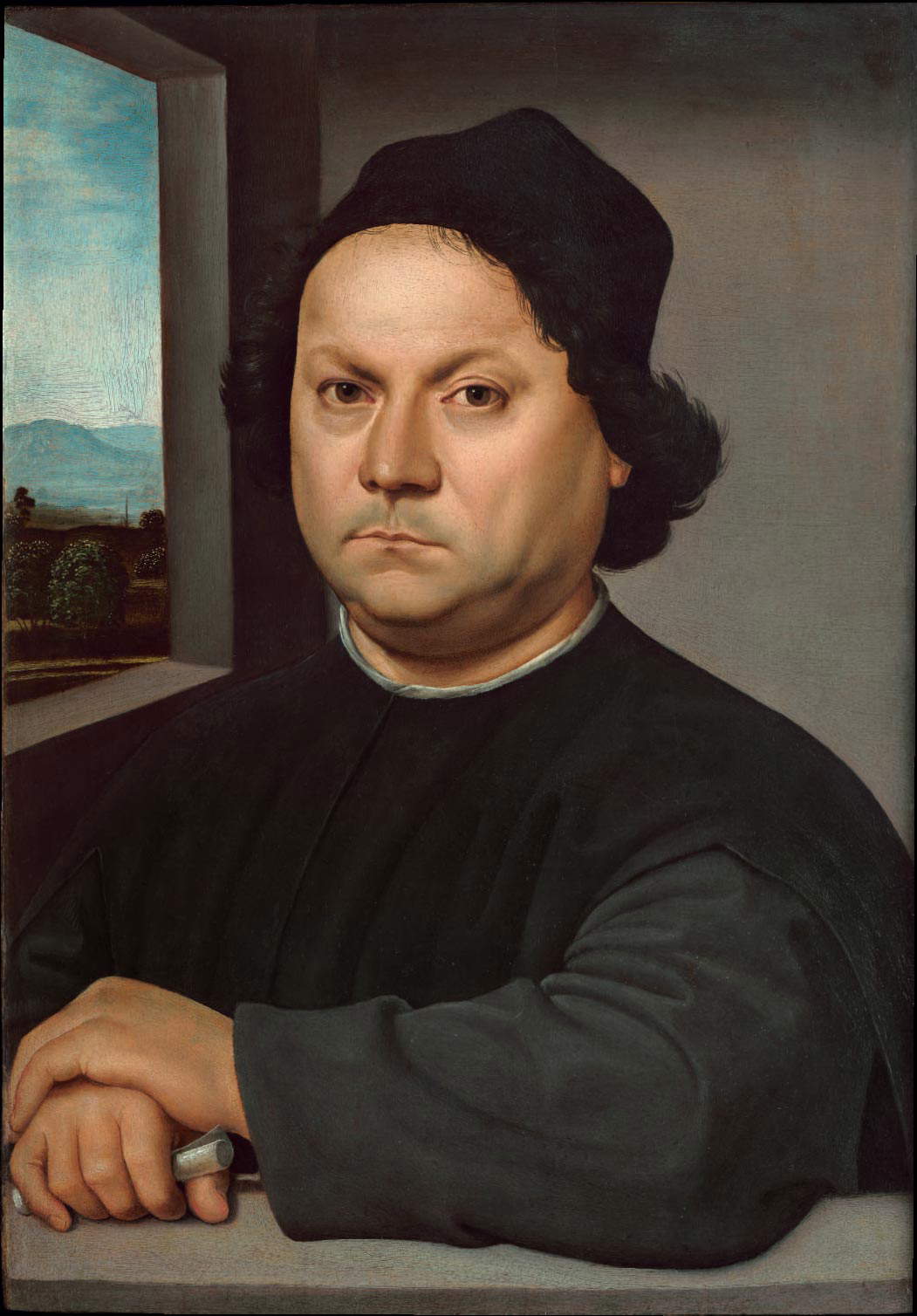

We go upstairs to learn about the portraitist Perugino, to whom the fourth section of the exhibition is devoted. There are some peaks of Perugino portraiture, such as the Portrait of Lorenzo di Credi, which arrives on loan from the National Gallery in Washington, or such as the Portrait of Francesco delle Opere, which are surprising for their very high realism, for the care with which the artist lingers on every single element of his subject’s face, for the very fine gradations of light that enhance the features of his characters: Perugino’s long reflection on coeval Flemish portraiture is evident, just as it is clear that, in this genre, the Umbrian painter at the time had very few who could equal him. One finds here, moreover, the most striking novelty of the exhibition: the Portrait of Perugino in the Palazzo Pitti, hitherto variously assigned to the young Raphael or Lorenzo di Credi, is now given to Perugino, who would therefore have self-portrayed himself using the same cartoon used for the self-portrait that stands at the center of the Sala delle Udienze in the Collegio del Cambio. The attribution to Perugino of this penetrating portrait is nothing new (already Adolfo Venturi and Ettore Camesasca, a hundred years ago, had assigned it to Pietro Vannucci, at a time when it was still unclear who the man depicted was), and it is dusted off on this occasion (after decades in which critics had leaned toward other names) by Marco Pierini, who, with the staff of the National Gallery of Umbria, took measurements on the Palazzo Pitti portrait and the Cambio portrait and found a millimeter correspondence, which would suggest the use of the same cartoon: according to Pierini there is no doubt about this. In an almost Morellian manner in the catalog, detailed images of individual elements are given for comparison: eyes, eyebrows, noses, locks of hair. The differences are mainly due to the fact that in the Cambio fresco, according to Pierini later than the Pitti Palace image, the artist “accentuates the signs of age: the corners of the mouth fold downward, the double chin becomes more prominent, the face widens,” making variations that, “like the elongation of the hair, are conducted directly on the plaster once the drawing has been transferred from the cardboard.”

The next room is followed by a section on Perugino’s Madonnas, capable of establishing a canon of beauty based on a haughty and somewhat detached grace that would have had wide fortune at the time: an example of this is the Madonna and Child with St. John lent by the National Gallery in London, where the Virgin, with her oval and delicate face, her round eyes with large eyelids and lowered gaze, finds almost a sister in that of Lorenzo di Credi’s tondo, with which she is placed in direct comparison. Of great interest is another comparison, that between the Madonna of the Confraternity of Consolation, one of Perugino’s most famous and best-documented Madonnas, and a Mule Head, which, as can be seen from the holes along the contour lines, evidently served as a cartoon, although it is not possible to know exactly for which works. One cannot help but notice, however, the very close resemblance of the face, oval, slightly recumbent, framed by hair with parting in the middle, with a small, well-proportioned nose and long, arched eyelashes. The section also offers a lunge into workshop practices, as a demonstration of which comes, again from the National Gallery in Washington, a work produced by Perugino’s atelier (it is a Madonna and Child Enthroned with Angels between Saints Rose and Catherine of Alexandria), functional in giving the public an idea of the qualitative gap between the master’s works and those of his collaborators. The section closes with a Madonna and Child by Antoniazzo Romano, the principal artist of 15th-century Rome, with whom Perugino collaborated at the time he moved to the Eternal City: Antoniazzo, as can be seen from this panel of his, was not impervious to the lessons of his Umbrian colleague.

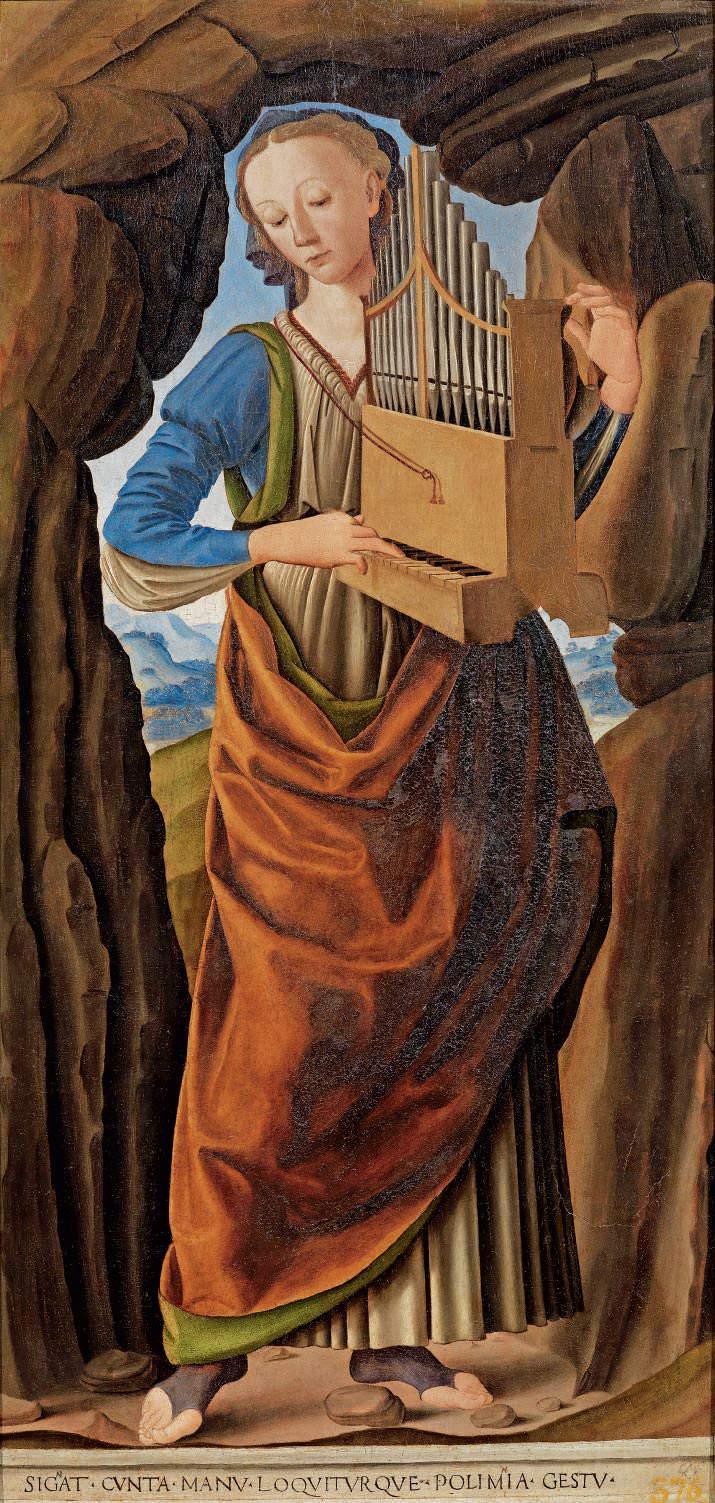

Toward the finale, the exhibition delves into one of its main themes, that of the Peruginese koine: the penultimate room lines up a long series of works by artists from all over Italy who were not insensitive to the innovations that Perugino managed to export outside Umbria and Florence. Rome, Lombardy, Tuscany, Bologna, Ferrara, Urbino, the Veneto, Naples: different areas of Italy in which Perugino’s language took root (in the catalog, essays by Massimo Ferretti, Giacomo Alberto Calogero and Orazio Lovino manage to trace a precise and rather exhaustive geography). The room opens with Giovanni Santi’s Polyhymnia, whose face shows the typical features of Perugino’s Madonnas, given also the close relationship that Raphael’s father had with Perugino (the two also had the opportunity to work together), while Macrino d’Alba is the artist who exports Perugino’s manner to northwestern Italy (the Piedmontese artist managed to see his Umbrian colleague’s works in Rome). Demonstrating clear debts to Perugino is the Neapolitan Stefano Sparano, present with the polyptych of the Madonna delle Grazie, and the suggestions exerted by the Scarani Altarpiece could not fail to appeal to the Bolognese milieu: Lorenzo Costa’sAssumption of the Virgin is a vivid witness to the spread of Peruginism in Emilia as well (the closest Emilian to Perugino is not missing either: Francesco Francia, on display with an Annunciation between Saints Jerome and John the Baptist). Francesco Verla, a “Peruginized Vicentine,” got to know Perugino during some trips to central Italy, from which he brought back a wealth of knowledge that enabled him to update his style on the basis of what Perugino was painting in Umbria at the beginning of the sixteenth century, while, at the end of the room, Domenico Beccafumi and Girolamo del Pacchia show how even in Siena people looked to the art of Pietro Vannucci. Grand finale with Perugino’s two early 16th-century summits, both painted in the same period as the artist’s other great masterpiece, the frescoes of the Collegio del Cambio: The Struggle between Love and Chastity, a painting of illustrious commission (it was executed for Isabella d’Este), although it can be included perhaps among the artist’s less happy things (thus “summit” mainly because of the importance of the client), and the Marriage of the Virgin, painted for the Chapel of the Holy Ring in Perugia Cathedral, and then sent to France during the Napoleonic occupation in 1798 (the exceptional return from Caen is one of the main reasons for visiting the exhibition). These are the works that, Rudolf Hiller von Gaertringen writes in the catalog, “confirm the claims of contemporaries that the artist was among the best Italian painters of his generation” and place him as a “character on the border of two epochs” capable of pointing “that road to the future that he had no desire to take.” Little desire, or perhaps fulfillment, or even fatigue: the fact is that his language would be destined to be short-lived, since by the end of the first decade of the sixteenth century the innovations of Raphael, Michelangelo, and Leonardo were already pressing in. But Perugino had nevertheless known how to be an original and innovative artist.

Perugino,

Perugino,How was Perugino’s style able to establish itself so widely? The reasons for the spread of Peruginism can perhaps be found in two main factors. On the one hand, the simplicity and pleasantness of the language spoken by the artist, based on idealized physiognomies, delicacy of the figures, and supreme clarity of exposition: characteristics that, Nicoletta Baldini noted in 2004, allowed Perugino’s art to assert itself in Savonarola’s Florence also because they were consonant with the instances of moral renewal of the time, and this despite the fact that the sources describe the painter as a not very religious person. But more generally, Pietro Vannucci found himself elaborating easy formulas, capable of responding to the needs of a devotion, both private and public, that demanded images of immediate comprehension, and at the same time he was able to move with dexterity even among a more demanding and more cultured clientele, which aspired to images that quoted the ancient or were based on precise iconological programs: the frescoes of the Collegio del Cambio are a blatant demonstration of Perugino’s versatility. The second reason lies in the resourcefulness of the artist, who was able to work, as we have seen, for patrons everywhere: this ability to meet requests was based on a highly organized workshop (a sort of “Renaissance Factory,” as Marco Pierini has defined it with extraordinary effectiveness) and on the entrepreneurial intelligence of Perugino, who at the height of his success was based in Perugia but kept very lively relations with Florence, where he went often, and also knew how to move wherever the situation required. Moreover, Perugino was not at all jealous of his ideas: unlike many other artists, Pietro Vannucci facilitated the circulation of his drawings and even his cartoons, thus allowing a reuse of his inventions that went even beyond his workshop. This operativeness resulted in a widespread presence of his works and drawings, throughout much of Italy: and for his contemporaries, as well as younger artists, he could not fail to become a point of reference. Of course, the ease of Perugino’s language was also at the origin of the short-lived parabola of Peruginism, which by the height of the second decade of the sixteenth century could already be said to have been outdated, but it was able to remain in vogue for some twenty years. And even in the years when the so-called “modern manner” was imposing itself, Perugino did not stop looking around and working with poetry and, sometimes, even with a certain originality: the topos of the last Perugino being boring and repetitive has now been disproved, but this is not among the aims of the exhibition.

The exhibition at the Galleria Nazionale dell’Umbria illustrates well and accurately the reasons for Perugino’s success, and it also hits the target when it dwells on Perugino’s art in the 1980s and 1990s, a period in which the artist built his success, and a period on which the 2004 exhibition had perhaps focused little, concentrating more on the beginning and the end of his career and on some important enterprises such as the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel and those of the Cambio. The merits of the exhibition, which already stands as a fundamental chapter in Perugino historiography, lie above all in having constructed a reading devoid of superstructures and capable of bringing to the public a Perugino truly cast within his own time (as, moreover, the very title of the exhibition implies), and in having avoided an unnecessary overdose that would have risked distancing the achievement of the objectives rather than facilitating it. Nevertheless, the public will not find even a meager selection at the National Gallery of Umbria: one can understand The Best Master of Italy. Perugino in His Time as a succession of milestones in the artist’s race toward fame and success. And from the exhibition, one will discover an artist who is not only fundamental, far from how historiographical reductions have often portrayed him, not only as the inventor of a new language, which blends the typically Umbrian sweetness, the rational layout of the Florentines and a terse luminosity of Venetian ascendancy, and which will later spread throughout Italy, but also as an artist who knows how to be varied and original. Against all the prejudices that affected him.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.