A fresh look at some famous paintings by Leonardo da Vinci. Martin Kemp's lecture

Leonardo da Vinci is a “painter of light.” This is how art historian Professor Martin Kemp, a longtime lecturer at Oxford University and one of the foremost experts on the great Tuscan artist, defined him during a lecture entitled Leonardo da Vinci. A fresh look at some very famous paintings, held last Feb. 15 at the Leonardo3 Museum in Milan on the occasion of the opening of the museum’s new interactive wall dedicated to the artist’s studies (read also here Federico Giannini’s interview with Professor Kemp).

Leonardo, it is known, is one of the most investigated, most studied, most explored figures in art history. That is not to say, however, that the research around him can be considered over: Leonardo da Vinci, by Martin Kemp’s own admission, continues to be a challenging figure: artist, scientist, philosopher, inventor, theorist, engineer, so many are the aspects of his multifaceted personality, and one of the terrains of future study, as the scholar explained in the interview mentioned above, will be precisely the transversality of his interests, since the different fields in which he worked have too often been studied separately. Considering Leonardo under multidisciplinary profiles may hold novelties and surprises in the future. Is it possible, then, to cast “a fresh eye,” as the title suggests, on Leonardo’s most famous paintings? This is what Martin Kemp tried to do during his lectio.

The early years: the study of the nature of the paintings made in the wake of Verrocchio

To get an idea of the extent to which Leonardo was a “painter of light,” it is necessary, according to Martin Kemp, to look at the fish held in Tobiolo’s hands in a painting, Tobiolo and the Angel, traditionally attributed to Verrocchio (it is preserved in the National Gallery in London), in which, however, some of the critics, including Professor Kemp himself, have wanted to recognize Leonardo’s hand, limited to certain details: in this case, the fish, painted by an artist who “is not simply a conjuror,” the professor stressed during the lecture, “but a painter of light, distinguished by an almost impressionistic technique,” would be revealing.

Leonardo’s career had begun in Verrocchio’s workshop, where the artist arrived at a very young age. “Verrocchio,” the British art historian continues, “used Leonardo as his collaborator, as he did with older artists, such as Lorenzo di Credi. But Leonardo had a special talent,” which enabled him to create masterpieces from a very early age. This is the case, for example, with theAnnunciation, a particularly elaborate work if one looks at the study of perspective, the accuracy in the rendering of natural elements, and the complex drawing. Leonardo, Kemp speculates, in these early stages of his career must have been employed in Verrocchio’s workshop as a specialist in the depiction of natural elements: this is how it appears to us in a work such as the Baptism of Christ, executed by Verrocchio together with at least two other artists in the workshop, one of whom is Leonardo, while the other (the one who executed, for example, the palm tree in the landscape) a much less talented unknown. “When Verrocchio was looking for something in his paintings that looked very much like nature,” Kemp says, “the person who was called in to deal with it was Leonardo.” Hence, then, the idea that in the National Gallery’s Tobiolo and the Angel the hand of the young Leonardo should also be discerned.

Also of Verrocchio-like character is another famous image from his younger years, the Portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci now in the National Gallery in Washington, in which Leonardo does nothing more than ’replicate’, in a certain sense, a sculpture by Verrocchio (the Lady of the Little Bouquet now in the Bargello Museum: Leonardo’s work, unfortunately, was cut at an unspecified time, otherwise we would have seen the noblewoman’s hands). The real novelty (as well as in the woman’s gaze, in the way she looks at the observer), again, lies in the already ’scientist-like’ manner in which Leonardo deals with the natural datum: Martin Kemp, in particular, draws attention to the landscape and the verisimilitude of the juniper that appears behind the protagonist.

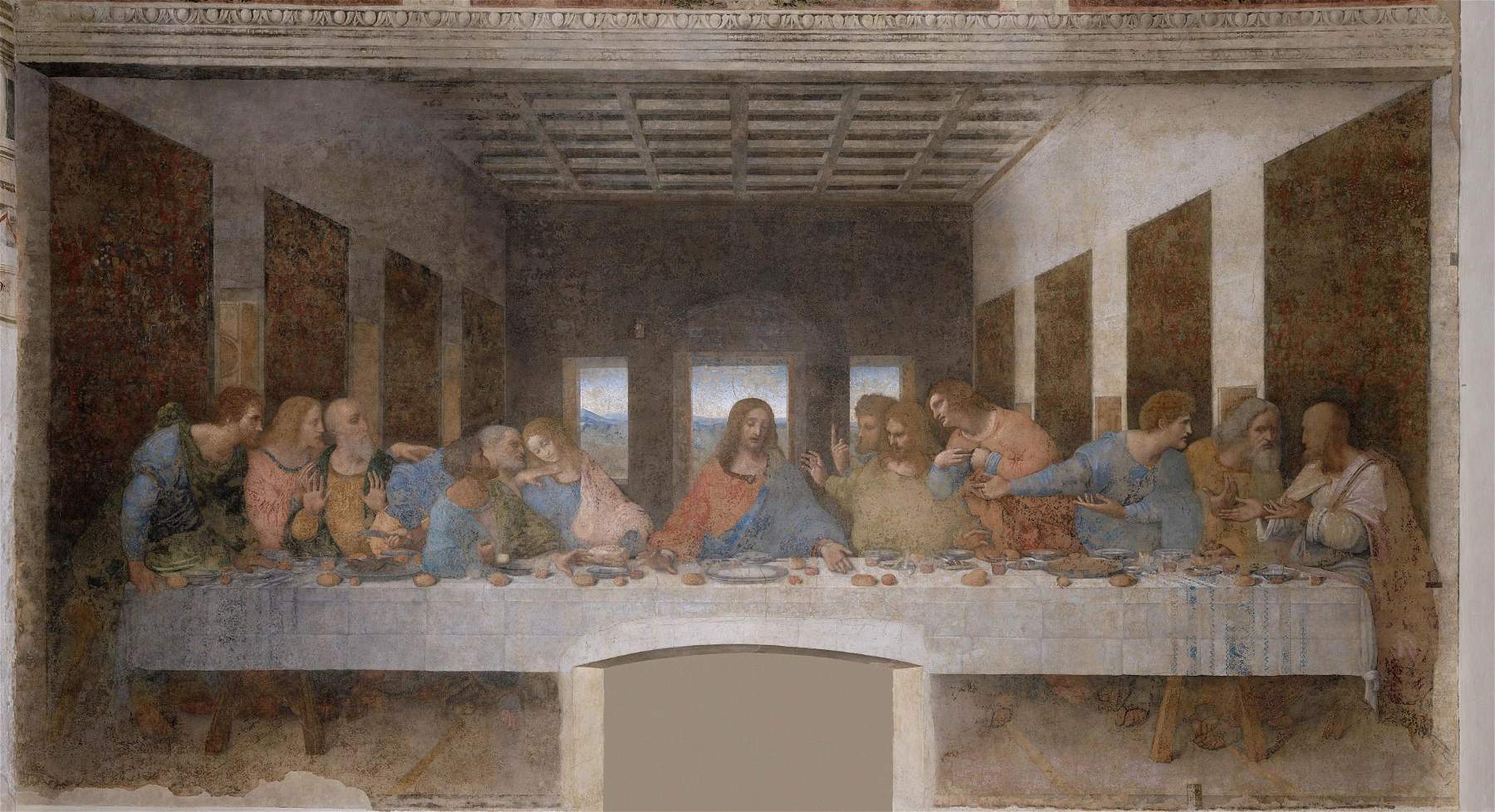

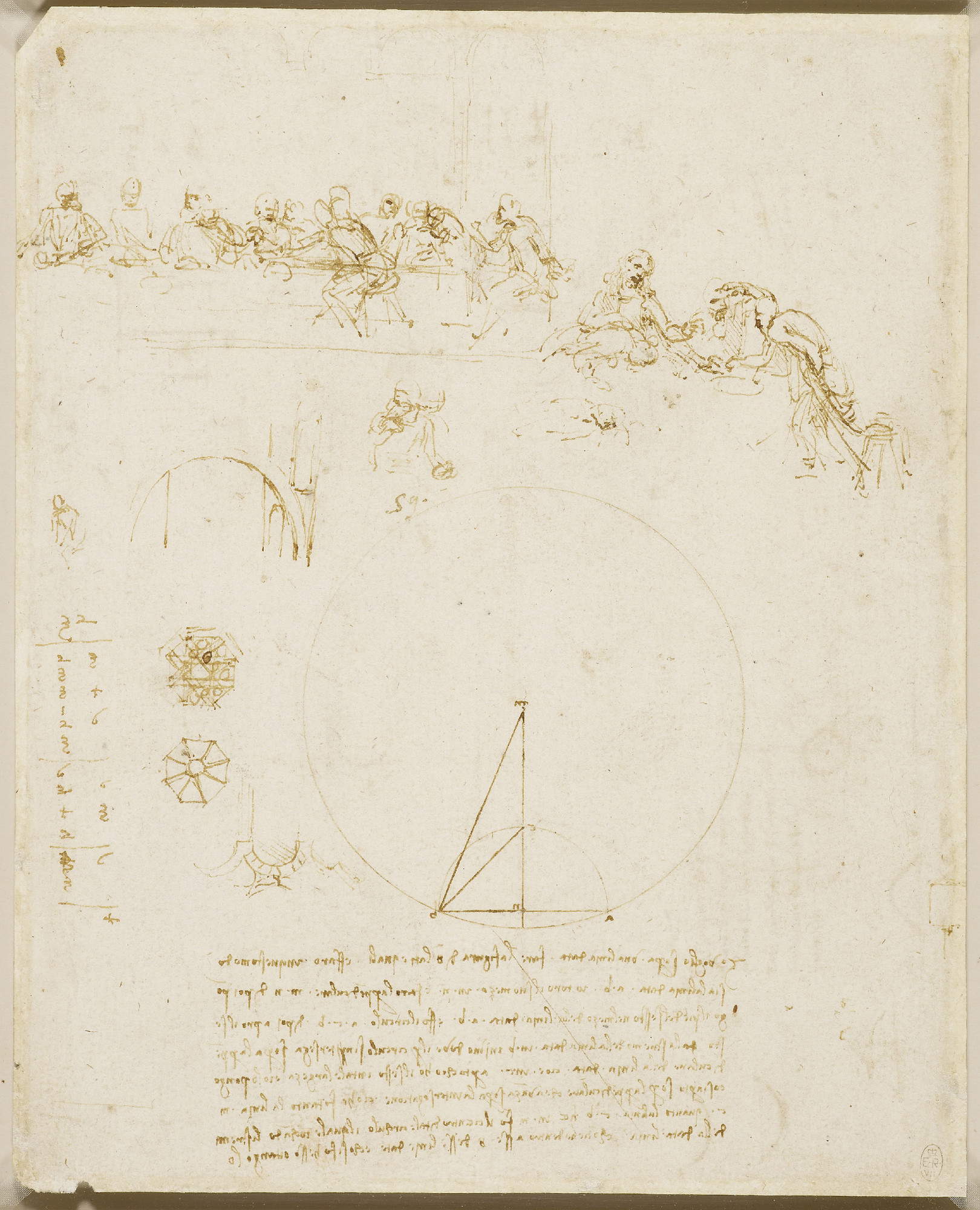

The representation of time in theLast Supper and the Battle of Anghiari

There is another phenomenon in which Leonardo is interested: time. And he would give proof of this in the celebrated Last Supper painted between 1494 and 1498 in the refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. Leonardo’s Last Supp er is now one of the most visited museums in the Lombard capital. “I have long thought,” said Martin Kemp, “about how Leonardo worked on the notion of ’time’ and how the latter is reflected in his paintings.” If one looks at the studies for theLast Supper, one can easily see how Leonardo considered the different motifs, the different moments of the Gospel episode. There is a drawing, preserved in Windsor, which can be considered a study for theLast Supper, in which we see Christ doing something he could not have done on the finished painting: he is participating in the conversation with the apostles, he is pointing to the objects on the table. “We don’t have to imagine it as a serious preparatory study for the final painting,” says Kemp, “but it’s interesting because of the way Leonardo studies the unfolding of the story, from right to left,” all following a kind of geometric diagram, with Judas standing on the right side of the table, getting up and initiating the narrative. “The fluidity of time in Leonardo is not an accident,” the scholar explains, but is an intended effect: Leonardo thinks of narrative as the telling of a story, so in his scene we see not so much a moment frozen in time, but an episode that extends in time. This is also revealed by certain details, for example St. Thomas pointing toward heaven, or St. Peter clutching a knife: details that do not embody mere symbols, but introduce elements of a very extended story. "Time, in theLast Supper, is dealt with in a very subtle way indeed, and it is related to the philosophy of Leonardo da Vinci," who regarded time as an indivisible continuum .

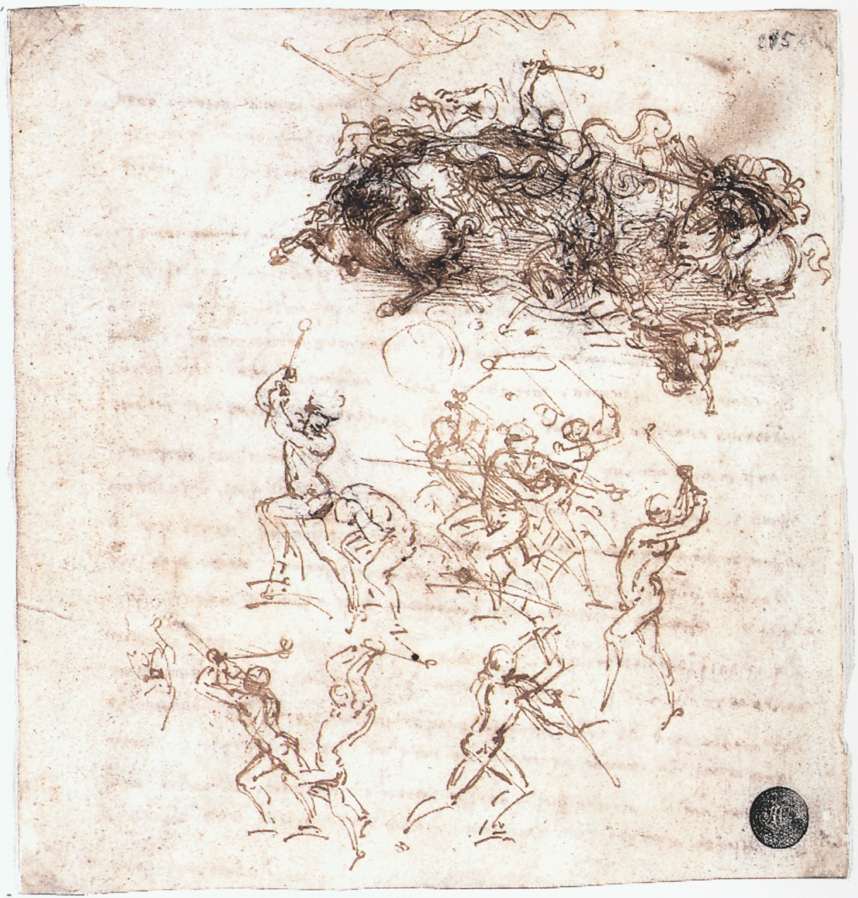

Even the Battle of Anghiari, known only through copies or derivations, since Leonardo failed to complete work on the part of the Salone dei Cinquecento in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio that was to house the painting, can be thought of as a continuous narrative. “It’s a bit like someone wrote the script for a battle scene in a movie,” says Martin Kemp. And it is Leonardo himself, in his Treatise on Painting, who provides detailed instructions on how to execute battle scenes: “You will first make the smoke of artillery mixed infra l’aria together with the dust moved by the movement of the horses of the combatants; la qual mistione userai così: the powder, because it is an earthly and ponderous thing, and although by its thinness it easily rises and mixes infra the air, nevertheless it willingly returns downward, and its supreme mount is made from the thinnest part; therefore the less it will be seen, and it will appear almost of the color of the air. The smoke that is mixed between the dusty air, when it rises higher to a certain height, will seem dark clouds, and will be seen in the summits more expediently the smoke than the dust. The smoke will hang in somewhat blue color, and the dust will draw to its color. From the side that the light comes will seem this mixture of air, smoke and dust much more shiny than from the opposite side. The combatants, the more they are within said turbulence, the less they will be seen, and the less difference will be from their lights to their shadows. Thou shalt make the faces and persons and the air near the arquebusiers redden together with their neighbors; and said redness the more it departs from its cause, the more it is lost; and the figures which are between thee and the light, being far off, shall appear dark in a light field, and their legs, the nearer they come to the earth, the less they shall be seen; for the dust is there thicker and thicker. [...] Thou shalt make running victors with hair and other light things scattered in the wind, with their eyelashes low, and they shall chase contrary limbs forward, that is, if they send their right foot forward, let their left arm also come forward; and if thou makest any fallen, thou shalt make him the sign of slipping up through the dust led in bloody mud; and around the mean liquidity of the earth thou shalt make them see printed the treads of the men and horses of there past. Thou shalt make some horses drag their lord dead, and behind that leave for dust and mud the mark of the dragged body. Thou shalt make the vanquished and beaten pale, with their lashes high in their conjunction, and the flesh that remains over them be plentiful with sore crepe. [...] You may see many men fallen in a group over a dead horse. See some victors leave the fighting, and come out of the multitude, netting with their hands their eyes and cheeks covered with mud made by the tearing of their eyes because of the dust. Seeing the rescue teams stand full of hope and suspicion, with their eyelashes sharpened, making a shadow to those with their hands, and looking about among the thick and confused fog to be attentive to the captain’s commandment; which you will be able to do with your staff raised, and running towards the rescue showing him the part where it is needed. And some river, in it running horses, filling the surrounding water with turbulence of waves, foam and confused water leaping towards the air, and between the legs and bodies of the horses. And make no place flat without the treads filled with blood.”

Vinciano begins his description by starting with science, and in particular physics, since the way he suggests painting dust and smoke is nothing but physics of dust and smoke, which is “very characteristic of Leonardo,” Kemp points out. There is, in Leonardo da Vinci’s work, a sense of time (and of speed, the scholar adds, since we have to imagine a frenzied scene rendered with extraordinary verisimilitude) that has almost a cinematic quality: the horses running, the soldiers fighting hitting each other, those falling to the ground, those disappearing behind the dust. It is a dimension that, again, emerges mostly from studies: probably the same would not have happened in the finished painting.

The Mona Lisa read through Dante Alighieri

“What could be said again about the Mona Lisa?” wonders Martin Kemp during his lecture at the Leonardo3 Museum. About the Mona Lisa, perhaps the most famous painting in history, indeed everything has been said, but that does not mean that the possibilities of adding something meaningful to the interpretation of the work are precluded. In Milan, Kemp proposes reading the famous portrait of Lisa del Giocondo in light of a passage from Dante Alighieri’s Convivio . One has long wondered about the reasons for the attraction that the Mona Lisa has exerted on the viewer for centuries. Martin Kemp responds by asserting that this celebrated painting is characterized by the reasons that Dante describes in the very Convivio, and in particular in a passage of Treatise III: “And though it may be that some may have inquired where this admirable pleasure appears in her, I distinguish in her person two parts, in which human pleasure and displeasure most appears. Hence it is to be known that in whatever part the soul more adopts of its office, that that more fixedly intends to adorn, and more subtly herein adopts. Hence we see that in the face of man, there where it does more of its office than in any part outside, so subtly does it intend, that, by subtilizing itself there as much as in its matter it can, no face to any other face is similar: because the last power of matter, which [is] in all almost dissimilar, there is reduced to act. And therefore that in the face maximally in two places the soul works - however, in those two places almost all three natures of the soul have jurisdiction - that is, in the eyes and mouth those maximally it adorns and there it sets the ’ntento all to make beautiful, if it can. And in these two places I say that these pleasures appear, saying, ’in the eyes and in his sweet laughter.’ Li quali due luoghi, per bella similitudine, si possono appellare balconi della donna che nel dificio del corpo abita, cioè l’anima: però che quivi, avegna che quasi velata, spesso volte si dimostra.”

Leonardo, Kemp explains, obviously did not intend to illustrate Dante, but this passage is well suited to the Mona Lisa since, says the English art historian, what Dante returns in his treatise is “grammar of love.” Leonardo therefore poured his attention on the eyes and mouth of the Mona Lisa because it is through these two elements, Dante argues, that a person arouses our pleasure or disgust. A beautiful smile provokes pleasure because, Dante says, the eyes and mouth are the “balconies” of the building that is the woman’s body, inhabited by the soul: and through such “balconies” the soul manifests itself.

The Salvator Mundi

The Salvator Mundi has become most famous for the price it fetched at auction at Christie’ s in 2017: $450 million, the most expensive work ever sold at auction in history. It is a painting that has also sparked huge debates over attribution, with one section of critics arguing against and another in favor. Martin Kemp has long been among those who support Leonardo da Vinci’s autography. It is, meanwhile, a highly replicated invention: indeed, there are numerous copies derived from Leonardo’s original. However, Kemp points out, in the other versions there is none of the “hair physics” found in the Salvator Mundi that went to auction at Christie’s, that is, the realistic movement of the hair, the way light reflects off it, the very way it is painted. This is evidence of an artist who understands the scientific significance of the movement of hair, studied exactly as one studies the movement of water, according to a famous image by Leonardo.

Another element that led Kemp to consider attributing the work to Leonardo is the crystalline sphere that the Savior holds in his hand: it is rock crystal, as can be seen by observing the bubbles imprisoned beneath the surface, and as was confirmed to Kemp by experts in mineralogy. In Martin Kemp’s opinion, this element, in addition to being described with a very high degree of precision, typical of Leonardo da Vinci, also introduces an iconographic novelty, in the sense that we are no longer dealing with a Salvator Mundi, but with a “Savior of the cosmos.” Finally, the fact that the work has parts that can be seen more sharply and others that are more blurred could be an allusion to that “double truth” to which Leonardo da Vinci alludes in his later paintings, and with which Martin Kemp concluded his lectio. There are essentially phenomena that we can know, and that fall within the domain of our faculty to rationally understand what is happening, and others that remain ineffable, that are beyond our knowledge. We should not think of Leonardo as a spiritual artist, not least because he himself wrote that he wished to leave the definition “in the minds of the friars, fathers of the people, who by inspiration know all secrets” not to concern himself with “the crowned letters [the Holy Scriptures] because they are supreme truth.” with his art, Kemp concludes, however, Leonardo wanted to make evident his “double truth.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.