Images of the sea in painting between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries

San Martino d’Albaro is today a crowded and densely urbanized district of Genoa, now completely incorporated into the city, and whose ancient physiognomy has become almost unrecognizable. In the late nineteenth century, however, it was a country hamlet just a stone’s throw from the sea. It had recently been annexed to the municipality of Genoa, but its life continued to remain separate from that of the capital, and it was here that, in 1890, a very young Plinio Nomellini (Livorno, 1866 - Florence, 1943), who had recently left the Florence in which he had attended the Accademia and forged solid friendships with the great Macchiaioli, above all Giovanni Fattori (Livorno, 1825 - Florence, 1908) and Telemaco Signorini (Florence, 1835 - 1901). And as the spring of 1891 drew to a close, Nomellini was joined by two colleagues who, exactly like him, were driven by a strongly innovative impulse: Giorgio Kienerk (Florence, 1869 - Fauglia, 1948) and Angelo Torchi (Massa Lombarda, 1856 - 1915). The three were moved (we know this from surviving correspondence) by the intent to conduct research into what Kienerk, in one of his letters, called the “new system” of painting: the prodromes of the manner that would go down in art history under the label of “pointillism.” In the postcard addressed to Signorini and mailed from Genoa dated June 5, 1891, Kienerk declared that “I like Genoa very much, but more than Genoa I like the sea,” and described to the experienced painter his typical day in Liguria: “I am staying in Via Minerva No. 6 interno 13, not far from Nomellini’s house. In a few steps we are in S. Francesco where we pass every morning to go to a narrow narrow street enclosed between two walls that leads us to the sea, and there from 7 to 11 (antimeridiane) in the shade of the rocks we paint. From 11 a.m. to noon we go home and eat something, and after that until 6 a.m. we work on portraits in charcoal. At 6 we have dinner and at 7 we go back to the sea and paint until we see each other. This is how I spend my days here in Genoa.” Torchi, for his part, in a missive also sent to Signorini on July 21 of that year, wrote: “our field of action is restricted to a few steps from the tower where you stay and often do not go out of the windows and terrace of the studio. From up here we enjoy the sea very well and can study it in its various manifestations from the point of view of our modern research.”

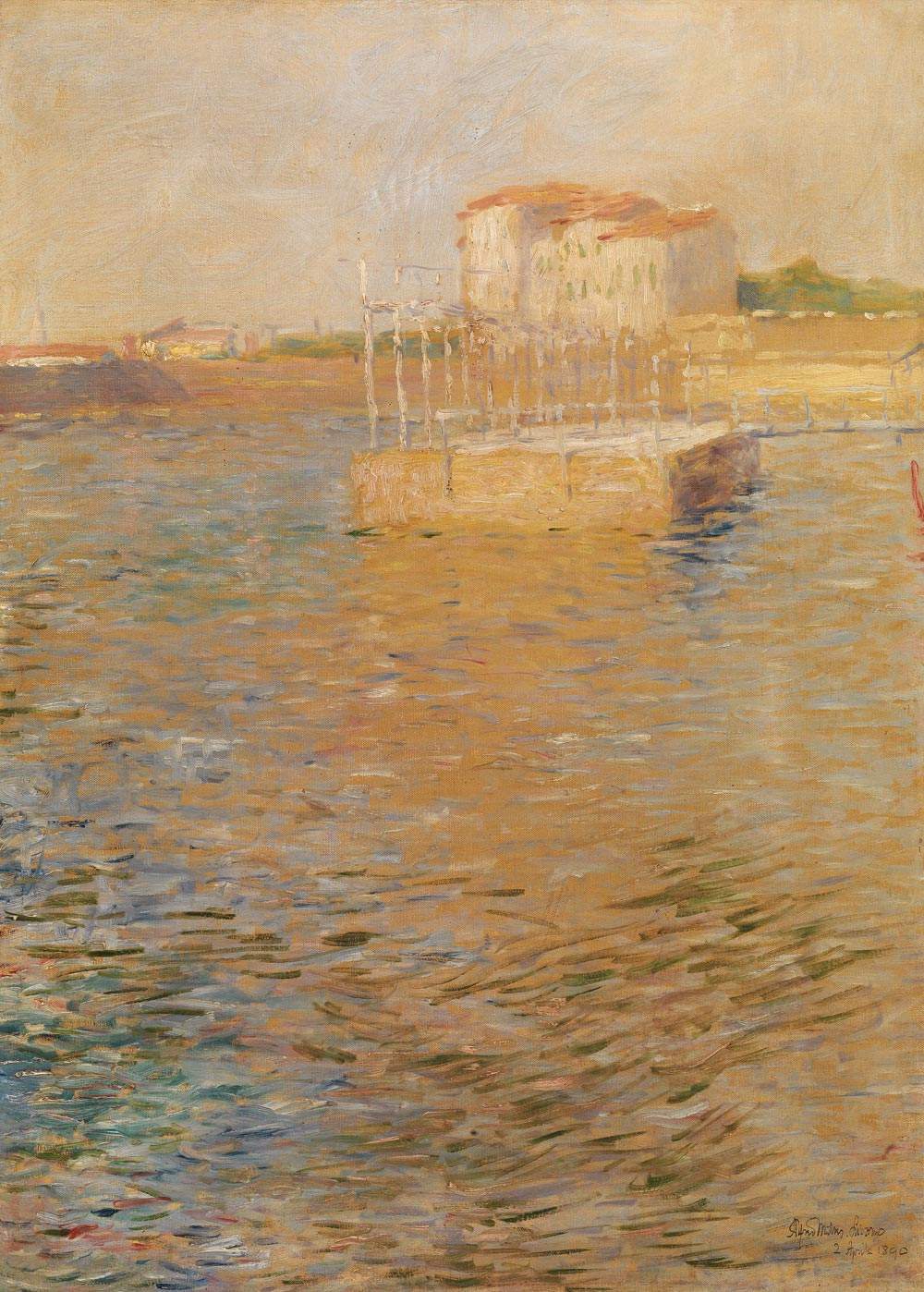

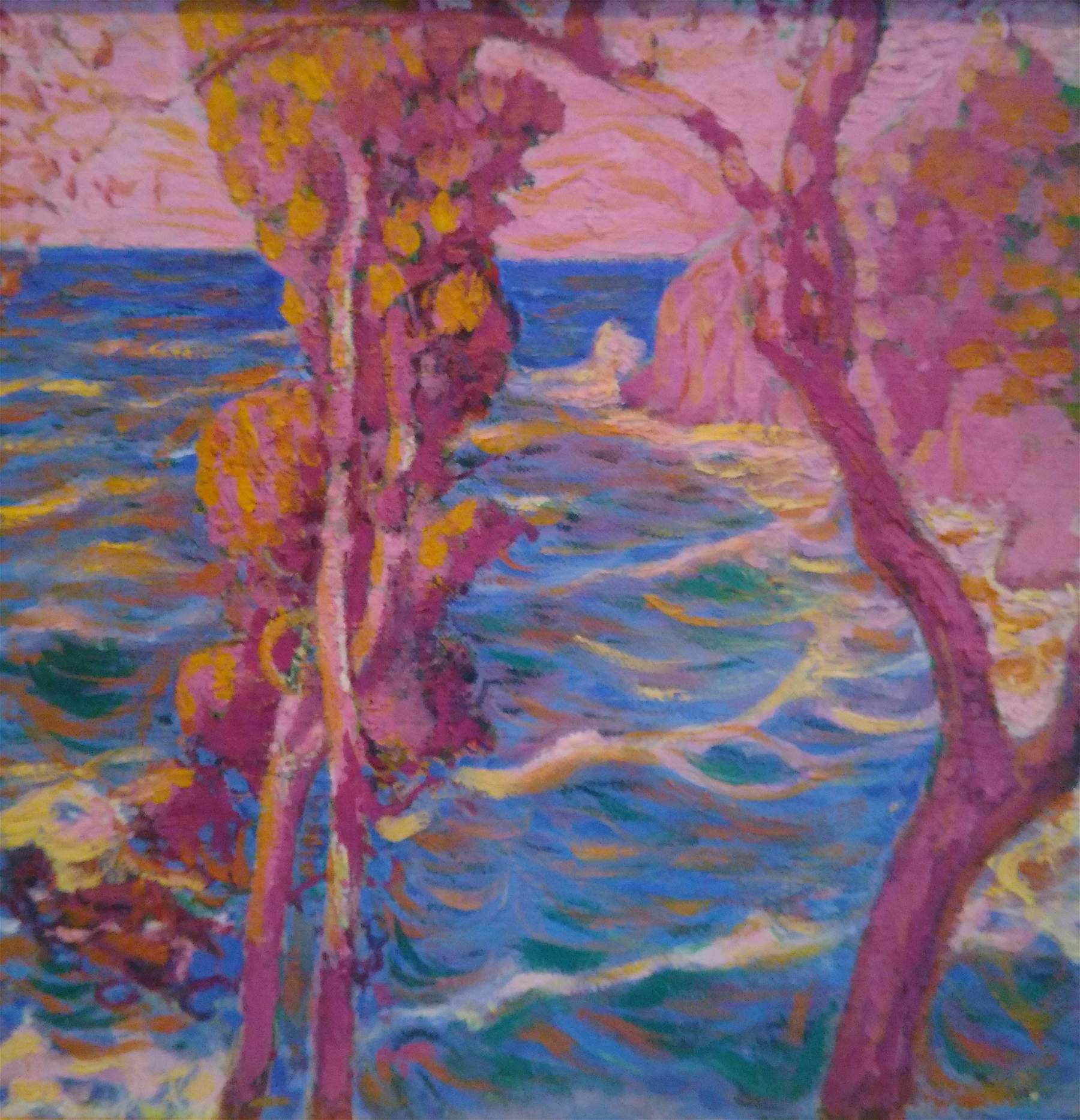

Trees by the Sea, a piece of Ligurian coastline that Kienerk breaks down under the light of the noontide that floods the foliage of the vegetation with golden rays, is one of the highest products of that Genoese sojourn and introduces, even with a certain precocity moved by the urge to experiment that animated the three young painters, a decomposition that set itself the’aim to overcome the Impressionist ascendancy still present, just by way of example, in a work such as the Bagni Pancaldi in Livorno that the Labronian Alfredo Müller (Livorno, 1869 - Paris, 1939) painted in 1890, offering observers one of the closest paintings to Monet ever seen in Italy. Kienerk, Nomellini and Torchi had other intentions: it is entirely probable, although there is no absolute certainty, that the Paris sojourns of Torchi and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo (the great Piedmontese, as is well known, was linked to Nomellini by a deep friendship that can be can easily be traced back to 1888, when the two met at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence) provided the group with the necessary cues and spurs to break away from the Impressionist verbiage and try new and bolder paths.

The one who showed immediate appreciation for the three painters’ researches was Signorini himself, who at the 1891-1892 exhibition of the Florentine Promotrice di belle arti recognized in Nomellini “the most daring researcher of the luminosity of nature,” the experimenter who had gone further ahead of the others and who manifested the most up-to-date instances ("Nomellini has done several things already, some of them before I arrived here, in which there is much good as an attempt especially of pointillé and vibration of light, and on this side it seems to me that he has somewhat progressed.") Still, Signorini preferred Kienerk to him: for his Trees by the Sea, he would lavish words of praise, emphasizing the sense of serenity and pleasantness emanating from his maritime view. Signorini had to follow with sincere interest the avenues opened in that fateful 1891, so much so that he himself wanted to try to open himself up to new things. Or at least, he wanted to try to set, on his profoundly Tuscan basis, the suggestions that came from France, as can be seen by observing, for example, the Ligurian Vegetation at Riomaggiore, works that the artist painted in 1894 during his stay in the Cinque Terre, and which he exhibited at the Venice Biennale three years later: the attempt to restore on canvas the vibrant clarity of the light of a Ligurian morning translates here into a painting that, for a moment, leaves aside the Macchiaioli synthesis and seeks the effect of atmosphere by operating, at least in the foreground, in an analytical way, and then lets the vegetation run toward the sea that merges with the sky as if it were a single entity.

It was, moreover, precisely at that juncture that the Florentine painter drafted what we can consider a sort of passionate declaration of love for the sea that bathes the Ligurian coast, made up of steep cliffs that, vertically, plunge into the blue expanse, of placid villages clinging to the tops of the promontoriesî, of crêuze and steep mule tracks that furrow the hills penetrating the dense scrub, sometimes bordered by dry stone walls, sometimes by vineyards forced to exploit the few strips of land useful for cultivation: “I owe [...] the knowledge of this country to the great desire I had [...] for a wider sea than that of the Gulf of Spezia. Not that the open sea is any less open along the Tuscan littoral, from Viareggio to Livorno, or through the Maremma, as far as Civitavecchia; but these countries, situated in plains among spacious countryside, in front of endless sea beaches, do not produce so much the effect of its vastness, as coming out of the narrow gorges of the mountains, where a country like this is planted perpendicularly on precipitous cliffs. And this Ligurian sea seen from this port of call, had such attractions for me, that most of the time I spent in admiration and desire to be able to reproduce it in its endless mass and prodigious details.”

The sea confirmed itself as a terrain in which to conduct experiments, and this could only lead also to vigorous clashes, such as the one Nomellini, in the turning year, had with his master Giovanni Fattori (Livorno, 1825 - Florence, 1908), who had tried in vain to warn his pupils against what he had defined, in a letter sent to Guglielmo Micheli, “the abyss into which they are about to fall,” namely, the initiation of a painting that looked to the Impressionists. It is a touching missive from Fattori, dated March 12, 1891, that determines the irrevocable rupture between the sixty-six-year-old master and the twenty-five-year-old Nomellini: in this very emotional and impassioned writing, Fattori regretted his pupil’s choices, and had come to the conclusion that the time had come when he could no longer consider himself his master. Nevertheless, he took care to send, to him who had been one of his most promising students, a loyal certificate of esteem, and to renew his profession of eternal friendship: “I thought it my duty to warn you and the others that you were following a path already traced 10 or 12 years ago, and that the very appreciable youthful fire made you see that the History of Art would register you as martyrs, and innovators, while the History of Art will register you as the most humble servants of Pisaro, Manet, etc. and ultimately of Mr. Muller [...]. You alone by justice I find you original as I said in the workers [...]. This is history and here I cease to say to myself your friend always, master never again! For I am with the old men, and I would know no more what to teach you-you will tell good Leghorn friends when you have occasion to write them-I shake your hand and am your affectionate friend.”

However, Fattori could count on a large group of artists, including young ones, who would remain artistically faithful to him. A few years before the irreparable rupture occurred, Fattori had finished one of his best-known masterpieces, Libecciata, a snapshot of a stretch of Leghorn coastline buffeted by southwesterly winds: leafy tamarisk trees with their foliage stirred by the fury of the libeccio, the shoreline shrubs bending under the violent gusts, the sand beginning to rise, the sea rippling and conspicuously white under a grayish sky, foreshadowing an imminent swell. Libecciata is from the early 1980s, and Fattori at that time had taken to cloaking his landscapes in poignant lyrical tones, inaugurating a taste for landscape unprecedented for his art, and not only. Exuding loneliness and melancholy, this painting. There is nothing idyllic about it, nothing reassuring: Fattori wanted his navy to be strongly communicative, and he evidently succeeded, if the commission that the City of Florence convened with the intention of evaluating some of the Leghorn painter’s works and then purchasing them, pointed out, in a report dated September 15, 1908, that Libecciata is a work in which the artist “even with very simple but precise means, without figures [...] has given to a short line of country the same force of expression as to a human face.”

This line, which to a certain extent anticipated the landscape-state of mind that would shortly thereafter be codified by the theories of philosophers Jean-Marie Guyau and Paul Soriau, masterfully interpreted in Italy by Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, was destined to have a certain amount of success. Guyau wrote that “to appreciate a landscape, it is necessary that in regard to that landscape one should feel harmony. To understand a sunbeam, it is necessary to vibrate with it, and the same is true for a moonbeam, it is necessary to tremble in the shadows of the evening, it is necessary to twinkle with the blue or golden stars, to understand the night it is necessary to feel passing over us the thrill of dark space, of vague and unknown immensity. [...] To understand a landscape, we must make it in harmony with ourselves, that is, we must humanize it. It is necessary to animate nature.”

Among the first to understand this identification between landscape and state of mind can be counted Eugenio Cecconi (Livorno, 1842 - Florence, 1903), who in 1903, with his Tramonto sul mare, painted a glimpse of the coast between Livorno and Castiglioncello, mindful of Fattori’s solutions, and enveloped in strong emotional intonations: here, naturalistic rendering and effects of realism combine to give the eye the impression of being on a hillside sloping down to the sea, but the vision is subordinated to a feeling of melancholy that pervades the whole atmosphere, and the eye is no longer only an instrument that, paraphrasing Guyau (who, moreover, to better explicate the assumption that our lives should merge with those of places, had cited the very example of the sea), measures the height of the hill, registers the motion of the waves, dwells on the movement of the clouds in the sky. The eye perceives, the eye makes landscape and concerning a single entity, the eye, in fact, animates nature by making the observer grasp, and perhaps experience, what the painter felt in front of the panorama: the stillness of the evening, the verdant coastline open to a silvery, calm and motionless sea, a few solitary tamarisk trees interrupting, at the center of the composition, the horizontality of the view, the clouds that do not thicken enough to prevent the last, pale glimmers of the waning sun from suavely gilding the gaps in the sky.

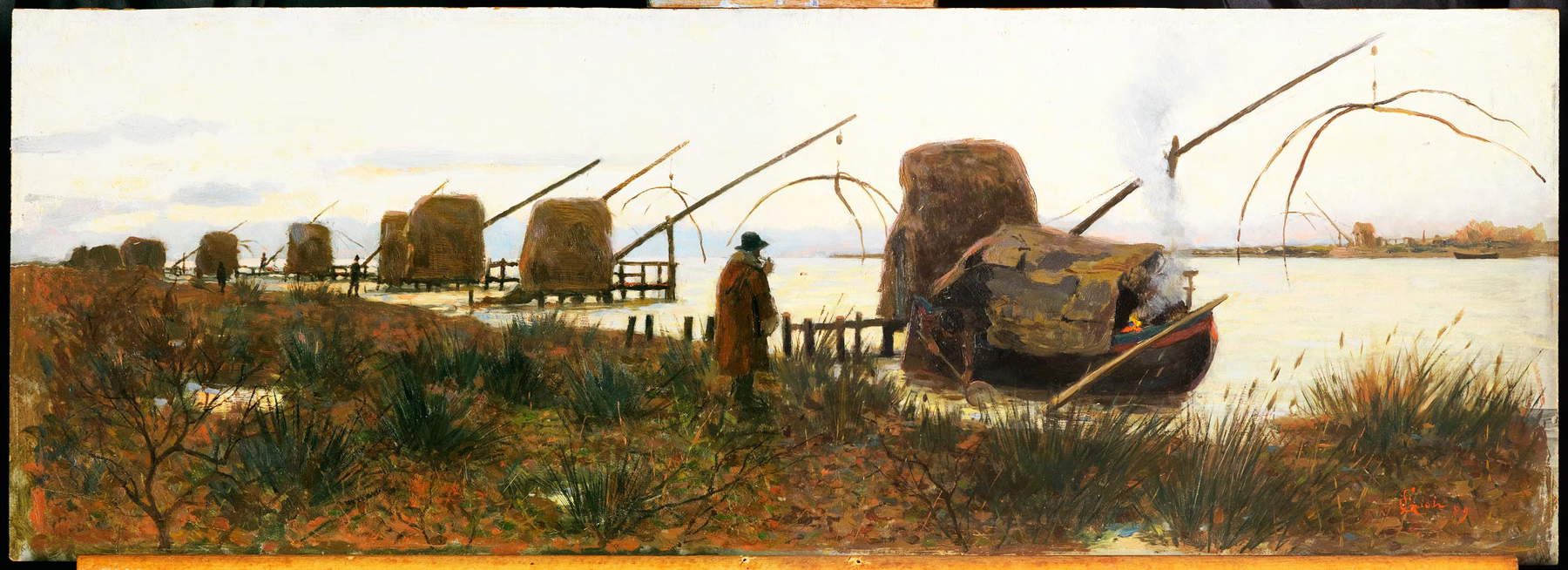

In Tuscany, the landscape-state of mind had another of its greatest interpreters in Francesco Gioli (San Frediano a Settimo, 1846 - Florence, 1922), another painter as reluctant to technical experimentalism as he was eager to test all the possibilities that could open up by merging landscape with poetry. And Gioli, too, in all likelihood considered the genre of the navy as the one that best suited his needs in terms of research into light and the expression of a feeling derived from the contemplation of a landscape, which in his artistic career knows an unstoppable evolutionary line, at least from the 1980s to the most advanced stages of his career. In contrast to the works of other landscape-state-of-mind painters, in Gioli the human figure maintains a significant relevance and is almost always present, in various capacities, in his sea views. In Bilance a Bocca d’Arno of 1889, one of his most famous paintings (not least because of the bold technical choice: a horizontal format in which the composition presents a strong oblique perspective cut, harking back to similar experiments that Fattori had attempted years earlier, with certain success), the human presence takes on the guise of a fisherman who wanders along the mouth of the river to check that the work of the scales, the large fishing nets typical of this coastal area of Tuscany, is proceeding in the right direction. And the feeling embraces all the backlighting of the scales, arranged in rows along the Arno to stand out against the pearly mass of the river that meets the sky on a gloomy day, and against the river vegetation rendered synthetically, according to the dictates of realist painting of which Gioli is an excellent interpreter. A realism that will appear secondary to the emotional accents in a late painting like the Child on the Beach of 1919: in the midst of the artistic avant-garde, Gioli, at the end of his career, was still capable of entrusting all his feeling to the romantic figure who, in a defiladed position, looks at the sea, and the painter catches her from behind. A lyricism that was also characteristic of the last Fattori: that, for example, of Sunset over the Sea, where the man standing alone and solitary in front of the sea is one of the last witnesses of the greatness of the Leghorn artist’s painting, a greatness that Ugo Ojetti (although to some extent conditioned by the preference he accorded to portraits, which he held in higher regard than to landscape painting) resolved in Fattori’s ability to give a “reasonable face of a man” to the landscape, that is, to define a piece of view that was not merely a representation of what was contained in that view, but that was also the expression of a feeling, that was a kind of photograph of the way the artist’s soul interpreted that landscape, rather than a simple, dry description of the landscape per se.

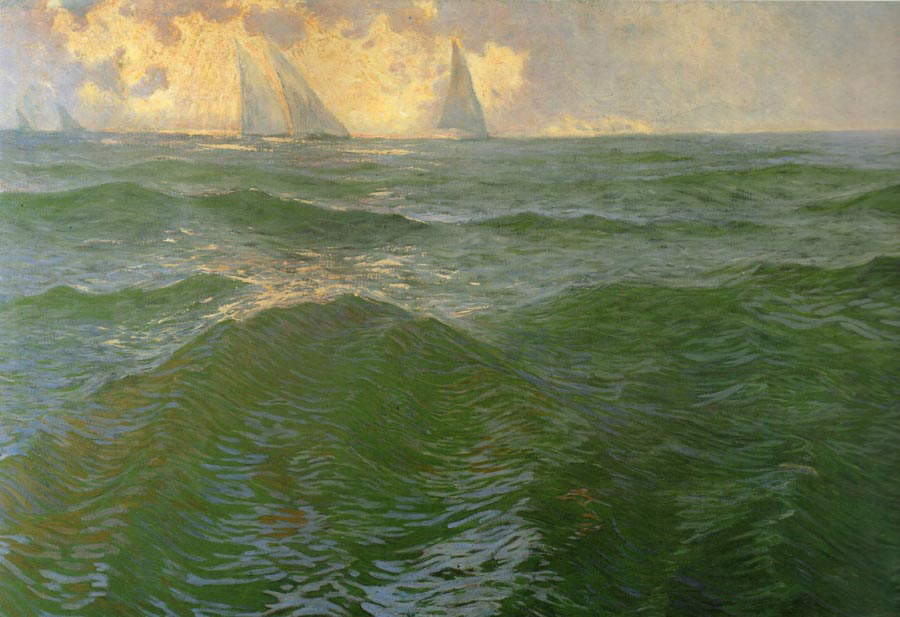

The early twentieth century were years in which Plinio Nomellini himself intensified the experimental vein of his painting, although without returning to the pointillist extremes touched in 1891 with the Gulf of Genoa, a painting that represents a kind of unicum in his artistic career and for which Nadia Marchioni, the scholar who in 2017 curated one of the most important retrospectives devoted to the great Tuscan painter, spared no adjectives or definitions, deeming it an “incredible” painting and recognizing in it the “most adventurous outcome in Divisionist experimentation,” such that it is an “impressive ’betrayal’ of the master’s graphic teaching.” The master, as mentioned, was Fattori, and the Gulf of Genoa was in line with the thunderous break with what Nomellini had learned from following him in Florence: having abandoned drawing, the search for a sharper luminosity was resolved with an unusual construction of the composition, which made use of a weave of minute taps given to the canvas with the tip of the brush. The overall impression might not appear so close to the real thing (far from it!), but the light that Nomellini had been able to infuse into his Ligurian navy was unprecedented for Italian painting and must have made a strong impression first of all on the two colleagues who had followed him in his Genoese sojourn, then on the other more attentive exponents of Italian pointillism, and then again on the artists of the previous generation who had the opportunity to admire the work at the exhibition of the Florentine Promotrice of 1891-1892, the same one in which Kienerk proposed his Trees on the Sea. But the results Nomellini caught should not have been so satisfactory if his Gulf of Genoa was criticized even by a broad-minded painter like Telemaco Signorini, who failed to appreciate the work of the young Leghorn artist: “what I frankly do not love,” he wrote in a review, “is to see Nomellini, more courageous seeker of the reality of character in every form, a mandolinata on the sea to bring back art with the fanciful romanticisms of Michetti and Fortuny.” In essence, more than the formal aspects, Signorini had clearly disliked the tone of the composition, which, with that chromatic range so clear, so terse, so dazzling, and with that female figure intent on playing the guitar, almost harked back to the experiences of southern Italian painters: interpreted by critics as a note of light-heartedness intended to evoke the climate in which Nomellini, Kienerk and Torchi were working in that short period of time, the inclusion of the girl playing the instrument is, however, also an isolated case in the production of Plinio Nomellini, who would no longer attempt to repeat the achievements of the Gulf of Genoa either on the formal level or on that of content.

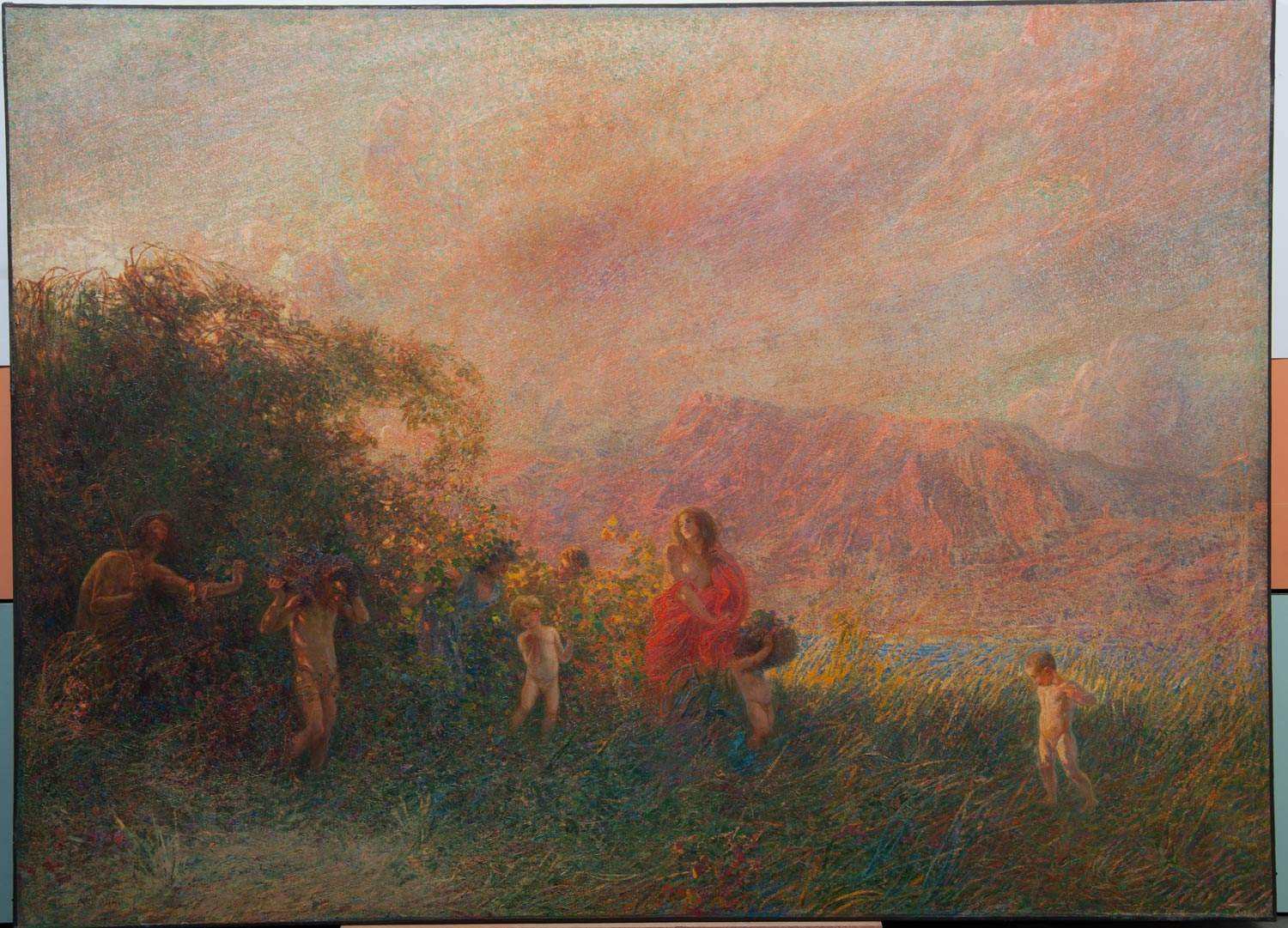

Nomellini’s painting went through different seasons and, as the scholar Silvio Balloni has rightly pointed out in a recent essay, few other artists like him were able to become admirable interpreters of the cultural climate of the time, almost offering a pictorial transposition of literary images and imaginations: it is in the paintings executed in the early twentieth century, dense, luminous, sometimes sunny and full of life, sometimes heroic and restless, always pervaded by a sensitivity poetic sensibility and a panic lyricism that knew no equal, that comes to life, in all its magnificent splendor, in all its immortal fusion of man and nature, the “cerula e fulva estate” that Gabriele D’Annunzio eternalized in the lofty verses ofAlcyone. In the lands of Versilia, so dear to both poet and painter, Nomellini settled from 1907, and here he produced some of the most admirable masterpieces that almost seem to give substance to D’Annunzio’s imaginative poem: this is more than a suggestion, since it is well known that Nomellini used to frequent poets and men of letters, and that he and D’Annunzio knew each other. And in a painting made around 1905, the reference to D’Annunzio’s lyrics appears explicit: Dithyramb, now kept at the “Paolo and Adele Giannoni” Gallery of Modern Art in Novara, is admired for the twilight light that gives reddish accents to the landscape, for the unrealistic view of the Apuan coastline that gathers, on one side, the fruit-filled land, and on theother the mountains laden with snow-white marbles that “reign over the bitter realm,” rendered in a splash of blue under the “threatening peaks” of the Luni alps, for the personification of the “wild, libidinous, vertiginous” summer. So much so that the painting almost seems to want to return in images theincipit of the third dithyramb ofAlcyone (“O great summer, great delight between the alps and the sea, / amidst such snow-white marbles and waters so dulcet, / naked the aerial limbs that line thy blood ofgold / smelling of aliga of resin and laurel, / lauded be you, / O great voluptuousness in the sky in the earth and sea / and in the faun’s flanks, O Summer, and in my singing, / lauded be you / you who filled with your richest gifts our day / and prolong on the oleanders the light of the sunset / to miraculous show!”). Paintings such as Ditirambo, or such as Baci di sole, a little later (its execution dates back to 1908), moreover inaugurate a new season in Nomellini’s art, coinciding with his stay in Versilia: a season in which the vitalistic impetus becomes almost the generating principle of his compositions, and where the fruitful union between man and nature is a founding element. Baci di sole, an intimate portrait of the artist’s wife and son, is an extraordinary and joyous poetry of light, a swarming vortex of flashes of light that flash through the shadows of the trees: Nomellini’s vibrant brushstrokes, at certain points mellow, at others stringy, and at still others rapid and given by small touches, give us back a moment of play in the shade of the leafy elms, which catch the sun’s rays without, however, preventing the star from reaching the limbs of the two protagonists, kissing them here and there with its furtive flickers.

Nomellini’s legacy would be picked up, in the Liguria from which everything started, by a painter born in the mountains but raised on the sea, Rubaldo Merello (Isolato Valtellina, 1872 - Santa Margherita Ligure, 1922), who was among the most singular Italian Symbolists and who interpreted the Livorno artist’s Divisionism “in the most complete way and with almost mystical faith” (so Gianfranco Bruno). It has been said of Merello that he eschewed both the scientifically controlled pointillism that was widespread in northern Italy and an excessively idealistic or spiritual vision, preferring to approach divided painting as Nomellini had done: with spontaneity and lyricism. His updating on Symbolist painting, however, had led him to feel, toward the views he painted, an intimate and deep emotional participation. Alongside certain postcard landscapes (images of pine trees silhouetted against the sea abound in his production, as do those of his beloved abbey of San Fruttuoso) are views where the colors, as Cesare Brandi pointed out, escape the control of theartist, weaving themselves autonomously over the painting and creating images endowed with an extraordinary strength, where the colors do not merge, but maintain their independence, almost as happens in van Gogh’s works. Of course: in all likelihood, Brandi pointed out, Merello never had the opportunity to learn about van Gogh’s art, and perhaps he did not even need to, having found his points of reference in Italy. But if one can advance a comparison with a great of the time, then it is “with certain landscapes of Munch, and because of the truly imaginary and dissident color he often manages to achieve.” So then, those paintings where Merello’s “chromatic madness” takes over, where “a yellow no longer calls out for its blue, but meets in a coral pink, and the shadows and reflections of the sea incite strange colors to perch, like birds of passage,” let them stand “next to the best Munch and some Bonnards”: Brandi assured that they would hold up to comparison.

In the same turn of the year, there were also those in other areas of Italy, insensitive to the novelties that were emerging between Liguria and Tuscany, who continued to retrace the furrow of tradition, albeit renewing it with ideas of certain interest and updated according to the prevailing international taste. In the Venetian lagoon, in the very years in which all of Tuscany was debating around the works of Nomellini, Kienerk, and Torchi, one of their Neapolitan contemporaries, who had, however, moved to Venice as a child, namely Ettore Tito (Castellammare di Stabia, 1859 - Venice, 1941) revisited the great Venetian painting according to unprecedented keys. Luglio, a work depicting “the Lido of Venice with a brood of beautiful children led by their janitors to take a sea bath” (as the critic and journalist Raffaello Barbiera described it when he saw it exhibited at the Brera Triennale in 1894, the year in which the painting was executed), offers the viewer the scene of a festive sea bath on a summer morning. The outstretched brushstrokes, the reflections of the sunlight filtered by the cloud cape, and the warm tones help create an extraordinary effect of diffused light that almost offers the viewer the sensation of mugginess permeating the air. The subject matter and the way it is approached, a snapshot of everyday beach life, hark back to the contemporary experiences of Joaquín Sorolla, Peder Severin Krøyer and the Skagen painters, Anders Zorn. Tito, however, had on his side a certain Tiepolesque lightness, a colorism rooted in the Venetian tradition from the sixteenth century onward, a natural inclination to construct his compositions with typically photographic framing, so much so that Roberto Longhi spoke of him as a “Paolo Veronese with Kodak.”

Tito was certainly not the only artist fascinated by modern photographic techniques: evidence of this are certain paintings by Francesco Lojacono (Palermo, 1838 - 1915), among the greatest landscape painters of the south, in whose art the sea often plays a major role. In many of his views of Palermo made at the turn of the century, photographic cuts and a tendency to emphasize foreground elements while leaving the city and mountains in the background to take on ill-defined contours are features from which Lojacono’s frequent use of photography leaks out: a use that the Palermo artist had made his own for several reasons, which included research on light (Lojacono, in particular, was attracted to the luminous relationships that the objects in the composition wove with the rest of the scene), the desire to freeze moments of daily life in the places he frequented, and the attempt to set, with the help of the photographic medium, the lines of the composition before moving on to the realization of the painting.

Lojacono, since 1895, was almost always present at the Venice Biennale: of the first four editions he missed only one. His participations were in a context in which the debate on overcoming the veristic view was alive, and it is worth noting in this sense how, in 1901, the great international exhibition in Venice saw the participation, for the first time, of a young Galileo Chini (Florence, 1873 - Florence, 1956), who with his work La Quiete, a view of the Tuscan hills caught in a moment of autumnal calm, was the interpreter of a divisionism mindful of the fusion of man and nature of his friend Nomellini (who had made his debut in Venice two years earlier, and was also present at the 1901 edition) but at the same time attracted by Central European symbolism. This tendency would emerge even more markedly in one of Chini’s youthful masterpieces, the 1904 Maestrale sul Tirreno, a work that reinterpreted the connection between landscape and emotion by effectively declining “the symbolist language of dazzling light” and reinforcing “the enigmatic undertones in the artist’s monogrammed signature” (so Maurizia Bonatti Bacchini). The artists of the new generation had decreed the definitive disengagement from veristic veduta, and shortly thereafter others would sever ties with Divisionist poetics as well. And for the genre of the navy a new season was opening, which would have its protagonists in painters such as Giorgio Belloni, Ludovico Cavaleri, Llewelyn Lloyd, Moses Levy, and Renato Natali. In the years when the fire of the avant-garde was being kindled.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.