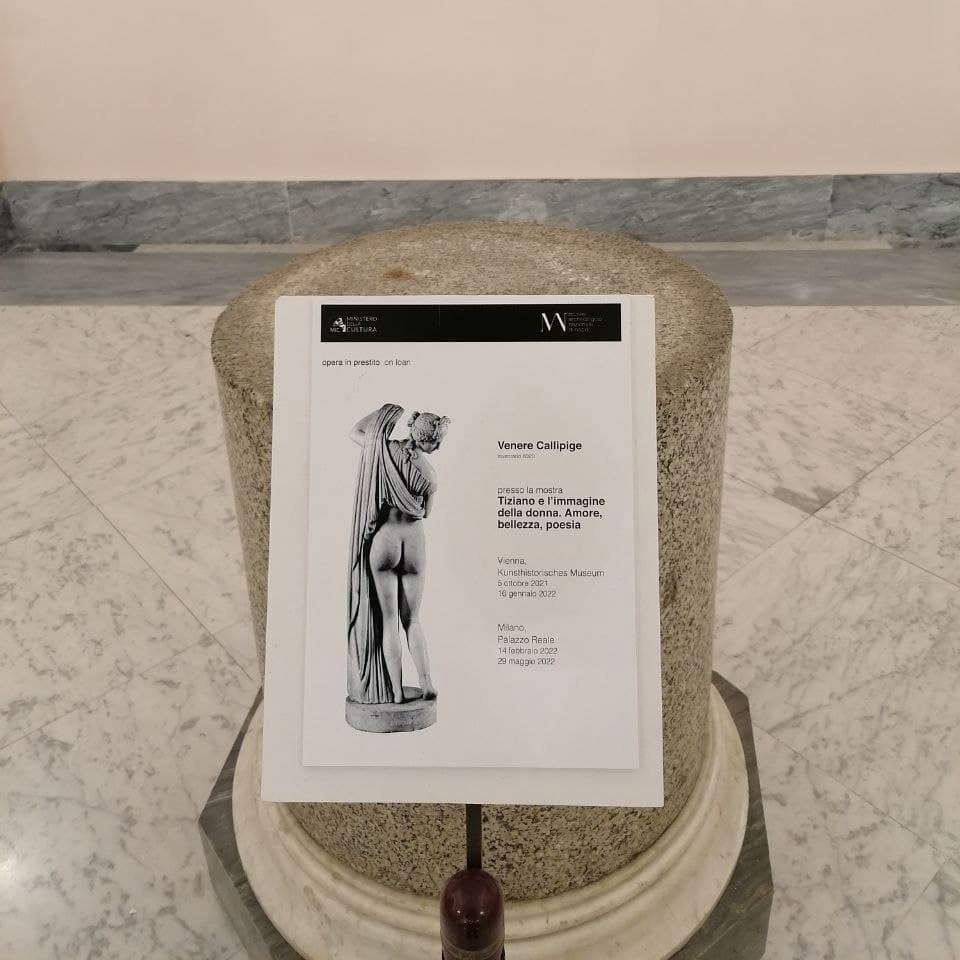

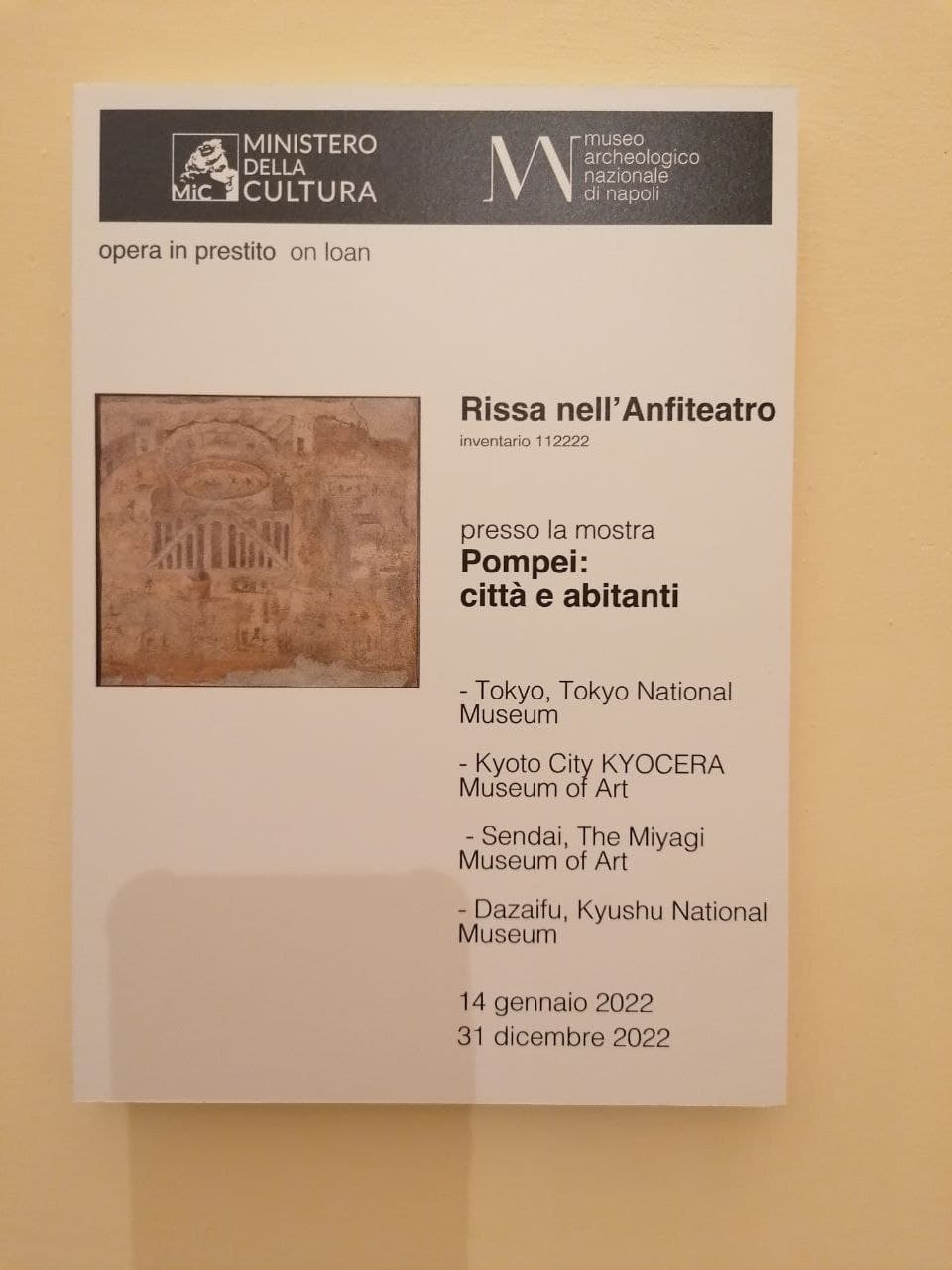

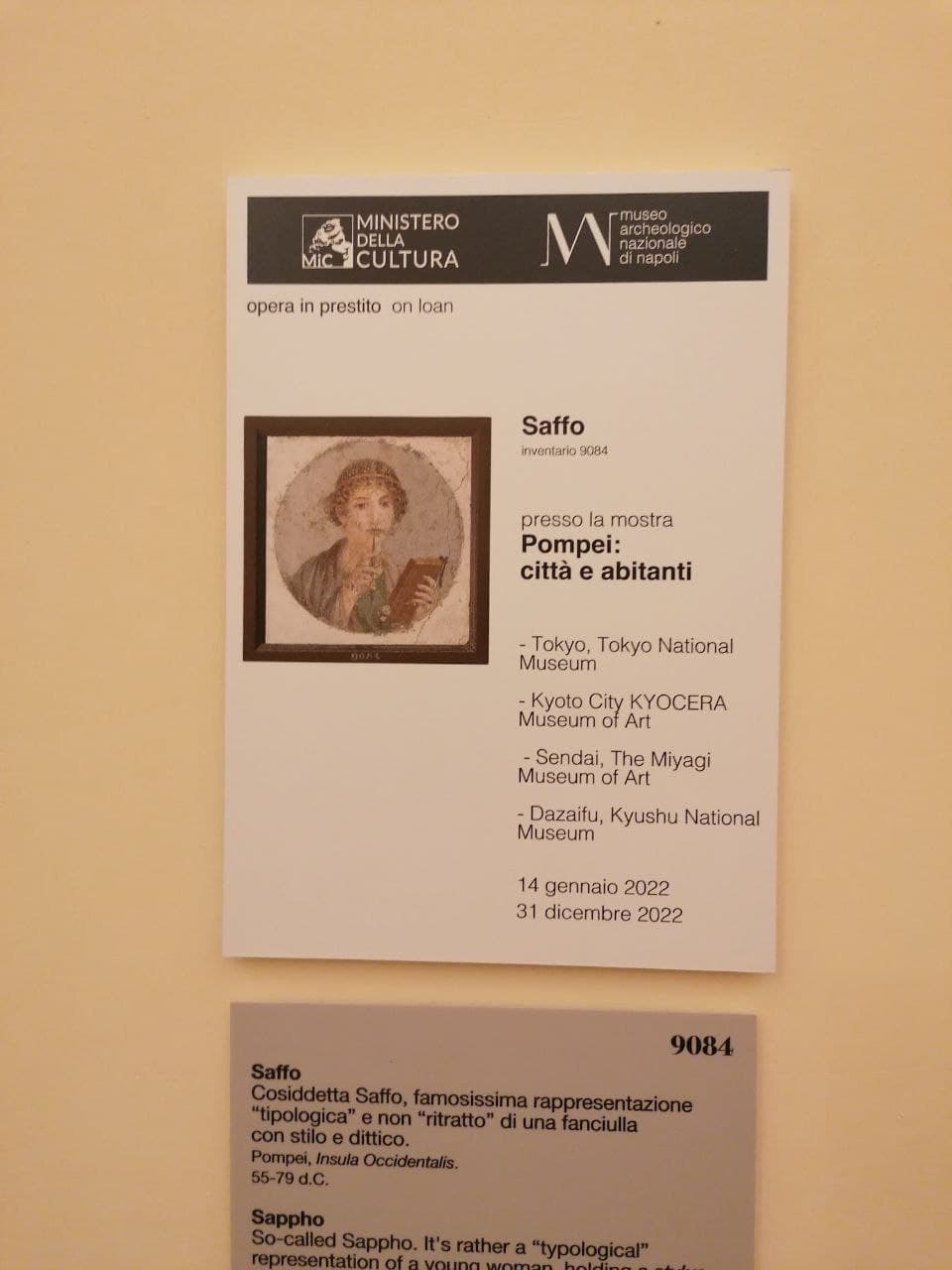

On January 16, the Pompeii exhibition opened at the National Museum in Tokyo , which after its stop in Japan ’s capital will move to other cities in the country: to Kyoto, Miyagi and Fukuoka, until December 31, 2022. Core and pillar of the exhibition are 160 artifacts from the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, which has already been without some of the works that have characterized its collections for more than 180 years for some months due to this massive move. They are in Tokyo, among others, the frescoes of Sappho, Terence Neo with his wife, Bacchus and Vesuvius; the mosaics of Plato’s academy, a famous memento mori, the Cave Canem; among the sculptures the faun from the “House of the Faun,” the Pompeian Doriforus; and then unique pieces such as the Blue Vase. Some of these moreover, such as the portrait of Sappho, have been absent from Naples since well before November 2021, because they are on loan to other exhibitions. Other iconic pieces, such as the Venus Callipige, have been absent for months for different exhibitions, but still far from Naples. An absence that users, at least those accustomed to frequenting museums, are noticing, already since December: on Tripadvisor there are very positive reviews and others that complain in no uncertain terms about closures and absences. Senator Margherita Corrado, and then the association Mi Riconosci, had already complained about the situation weeks ago.

There is a reason in this choice of the Museum. The Japanese newspaper The Asahi Shimbun, together with Nippon Hoso Kyokai - Japan Broadcasting Corporation, financed the restoration of the mosaic of the Battle of Issus, celebrated for the face of Alexander the Great, in exchange for this exhibition. And there is no doubt that the mosaic was in need of restoration. But the loan was not discussed publicly either nationally or locally. “It was known, because rumors ran, that a negotiation with the Japanese was going on,” explains a tour guide, who often works at the museum, "we were monitoring the Alexander mosaic, because there were fears it might leave. No one imagined that in its place half the museum would leave: in some rooms and some collections, the most important pieces are missing."

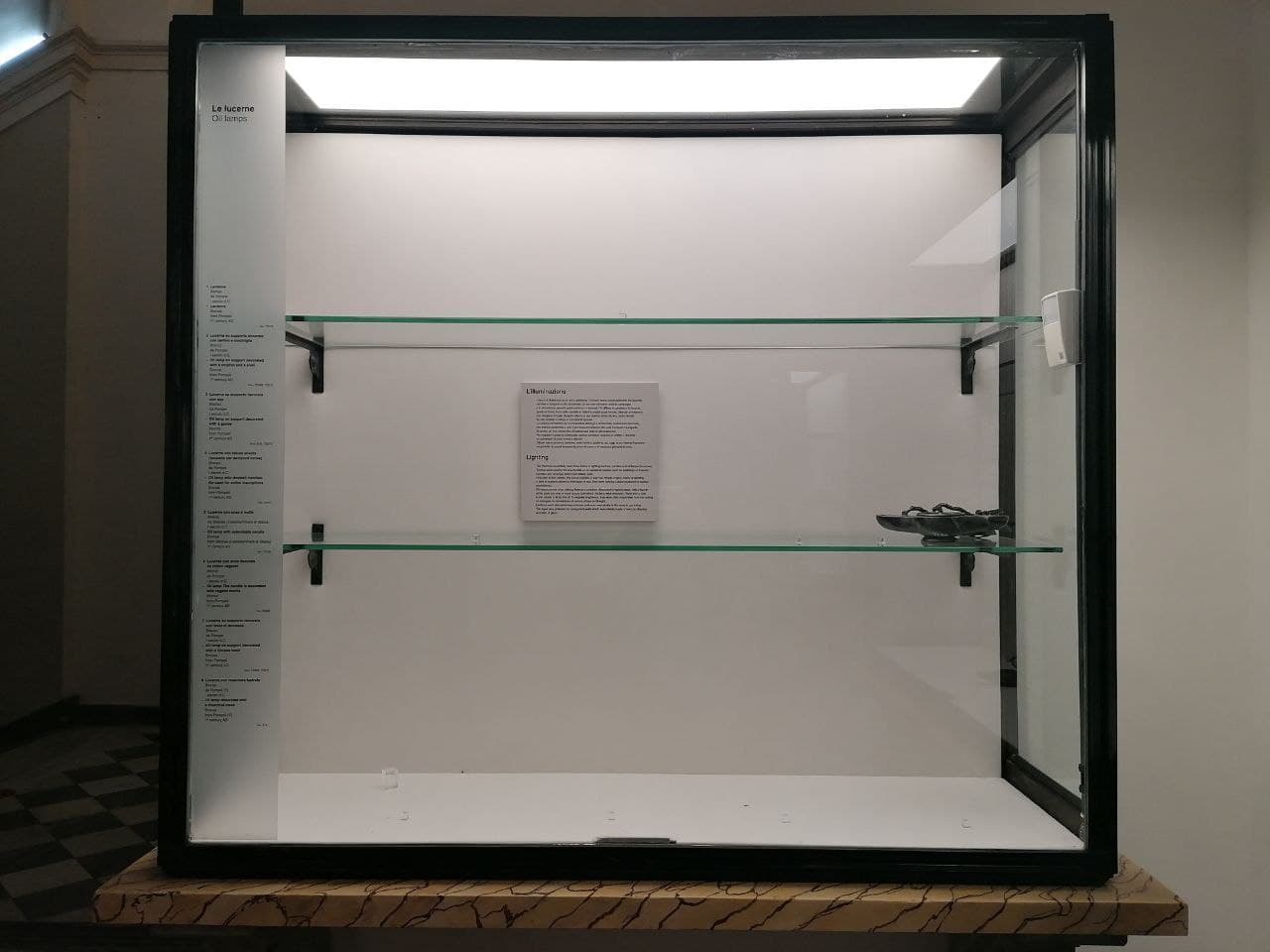

The “exchange” has produced the unfortunate consequence that these 160 artifacts are in Japan at the same time that the mosaic is not on public display because it is under restoration: in many sections the most important pieces are missing. While, for independent but parallel reasons, some sections have been closed for some time (Numismatics and Cumae), or open only on Saturdays and Sundays, or only some hours of the day: moreover, opening and closing times vary relatively frequently. “Checked from the website the closing times of the various galleries,” writes a user on Tripadvisor, “the Villa of the Papyri was listed as closing at 3:30 pm. On entry, at the ticket office no communication or sign indicating a time change. At 2 p.m. we try to cross the threshold of the Papyrus Gallery and two ladies inform us, while transfixed they lock the door that the closing time would be for 2 p.m.” To add to this, the Tyrannicides Room, which contains significant statuary, has been closed for weeks with a series of packing crates, without it being clear why.

The museum is probably aware of how this situation is inadmissible to the public, and on the site has chosen not to report absences, except for that (definitely justified) of the Alexander mosaic. At the same time, MANN has been opening new exhibitions with whirling frequency for months: the latest, photographic, "Sing Sing," while there have been exhibitions on gaming and gladiators (interesting fact, the exhibition on Gladiators has always been without the fresco representing the “fight in the Amphitheater,” which left the museum in March). The public in some cases appreciates despite everything, in others less so, especially given the lack of prior communication. “At least 40 percent of the mosaics, the Farnese Atlas and several other works are currently (January 2022) on loan at other museums,” writes another user on Tripadvisor. “Nothing against this, but I would appreciate being warned before paying the FULL price of the ticket. The Secret Cabinet collection moreover cannot be visited after 2 pm (why?). Again no warning prior to purchase of ticket (always full price at any time). Ditto regarding the closure of the Egyptian collection (again no warning).” Yes because despite the critical situation, the ticket price has not changed after doubling from 8 to 15 euros in the years 2016-2020.

The technical aspects related to these loans will not be discussed here: we know that practice and common sense would like iconic works characterizing a collection never to be lent, but we also know how this practice has been overtaken several times by political-economic needs. The Ministry’s guidelines clearly specify not to lend in cases where “the subject of the exhibition is too limited or too commercial for an object to travel,” but it is the Ministry itself then insists on loans, such as that of Vitruvian Man, for foreign exhibitions with works from Italy with an explicitly commercial slant (this Japanese exhibition will take off tens of thousands of tickets in a few weeks). Diplomacy is also done using cultural goods. Here, however, we want to discuss the appropriateness and credibility of our museums, given that the massive loan came at a time when other works, for various reasons, are also not on public display. A case reminiscent of the emptying of the Capodimonte Museum for a series of exhibitions in the United States a few years ago.

There is, however, one fundamental difference from the cases cited above: the MANN loans occurred in exchange for restoration. And this brings us back to the issue of what a public institution can do to obtain funds for a restoration: nowhere in the Cultural Heritage Code is there any mention of a loan of works, “sponsorship” occurs with brand association with the asset (the now-famous panels that cover palaces and churches from time to time, Tod’s on Colosseum tickets, plaques and so on), but the practice exceeds the law from time to time. Is opening to multiple loans to obtain funds, moreover without confrontation with the users, a viable and legitimate way forward? If it is, it should be discussed and possibly sanctioned through a legislative path, not left to informal practice. Because this is not an equal museum exchange, far from it. So there is a problem of disparity, of prestige, of the authority of our top cultural institutions, of bazaar museum risk: those who can pay can have. The National Archaeological Museum is not a small museum, it is an endless national museum and the most important Pompeian museum in the world: if it does not have the funds to restore the Alexander mosaic, it is a national problem. And if in order to get them it is driven to lend Japanese companies more or less everything they ask for in return (we were not at the negotiating table, but certainly it is hard to think of an exhibition richer in iconic pieces than the one set up in Tokyo) it is equally a problem of the credibility of our institutions.

And finally emerges, perhaps even more relevant, a problem of local credibility, of trust of the territory and visitors. Tour guides for months have been reinventing tours and itineraries: those who ask for a visit to the National Archaeological Museum in Naples have in mind many of the works that are not there now. And guides over the years have set their work around those works. But the same is true for visitors who choose an independent visit. Will those who paid to see things they didn’t find come back? Will those who have made the annual card, perhaps in order to repeatedly study or admire many of the things left for Japan, renew it? And above all, the “non-publics,” Neapolitans and Campanians who never or almost never enter the Museum, who have never felt MANN as their home, now that they see in the newspapers that those exhibits can stay in Naples as well as in Tokyo, what will they think, what will they perceive? In their own homes, no one lends the things they are most fond of for money. Unless they are on the verge of economic collapse and eviction: if the MANN in Naples is in this condition, it would be the case that both the city of Naples and the Italian Parliament know about it. If, on the other hand, the reasons for the loan are other, as seems evident, they should be explained and justified publicly.

The author of this article: Leonardo Bison

Dottore di ricerca in archeologia all'Università di Bristol (Regno Unito), collabora con Il Fatto Quotidiano ed è attivista dell'associazione Mi Riconosci.Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.