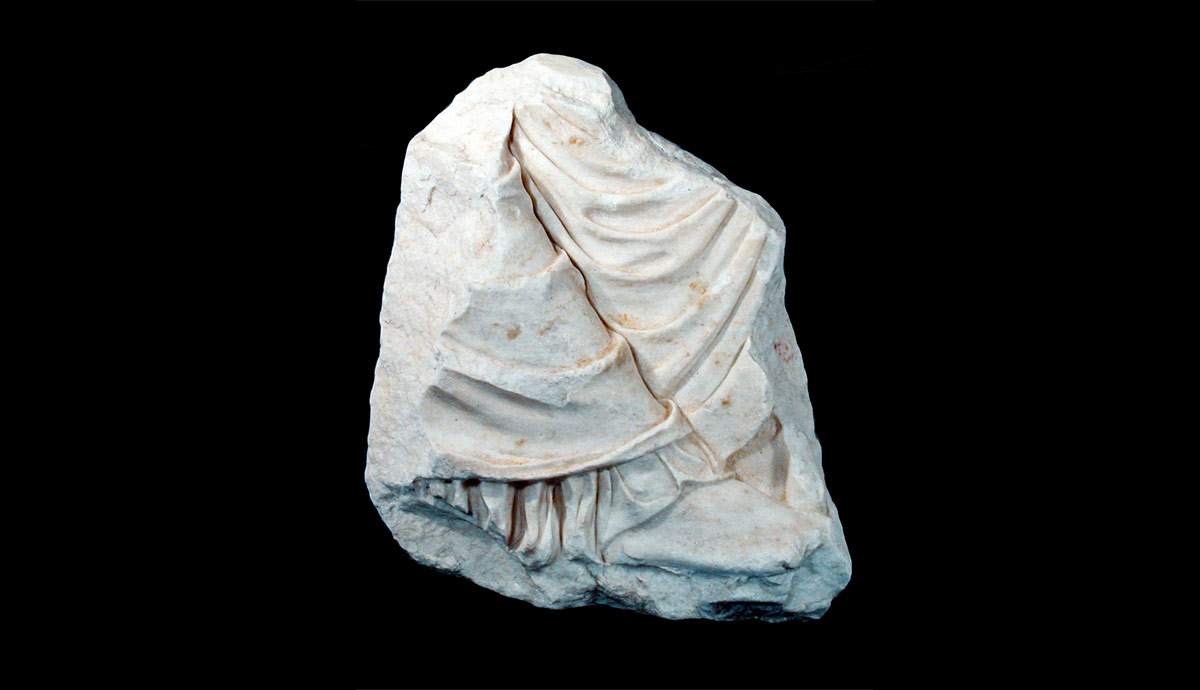

Beyond the cultural opportunities that need to be screened from time to time, how are works loaned from our museums? who authorizes? who expresses opinions? who verifies the conservation status of the goods and that their handling is done safely? The answers do not apply to all of Italy. If, instead of Giovanni Bellini’s Pieta from the Pinacoteca di Brera in Milan or Raphael’s La Fornarina from Palazzo Barberini in Rome having to be put on the move, it was one of the two Caravaggios kept at the Regional Museum of Messina or the bronzeAries from the Salinas Archaeological Museum in Palermo, the matter would definitely change. Autonomous Sicily, as usual, is a story unto itself. The recent loan of the Parthenon fragment from the very Salinas to Greece was an occasion to remind us that the Sicilian Region has given itself different rules. And not better ones.

In the island, in fact, the conditioning of politics (latent at all latitudes, let’s be clear) on choices that should be exclusively the prerogative of technicians has even been enshrined in law by the Musumeci government. At the Ministry of Culture, at least on paper, between Dpcm, decrees, circulars and guidelines, the administrative process is not polluted by undue interference. It is exclusively the technical offices that give the okay in case of a loan request for a Titian, a Caravaggio or even a lesser-known Marco dal Pino.

The issue for works owned by the Sicilian Region is now bouncing back, however, in all its gravity since Councillor Alberto Samonà declared, close on the heels of the article in which we recalled the unfairness of the agreement with the Met for the Morgantina Argenti, that he would like to “activate profitable collaborations with prestigious international cultural institutions,” as well as review that agreement. Now, if the entry of Sicily into an international circuit of cultural exchanges can only be an excellent statement of intent, quite another thing is that this can be worked on on the basis of regulatory experiments that are nothing more than a bad example of the use of autonomy. Let us see how this regional government would like to ship abroad, or even just across the Straits, the works of art housed in its museums. With a decree in 2019, it has seen fit to subordinate the pronouncement of the directors of these same museums to the councillor on duty put in the position of posing and disposing in defiance of even the opinion of the superintendencies, cut off from any decision on loans. But can one really believe that the director of a museum can freely express his or her opinion, determine, for example, whether a work is in the conservative condition to undergo a transfer or whether its absence would not result in a strong impairment to the enhancement actions implemented by the museum itself, and all this while remaining indifferent to the preliminary “appreciation” expressed by the alderman, as the aforementioned decree states?

Instead, politics should maintain and exercise policy direction, determine which policies of valorization of our heritage are first and foremost in the interest of that same heritage, and should step back from interfering with technical matters. Above all, least of all, it should exert pressure by entering into the administrative processes of loan approval.

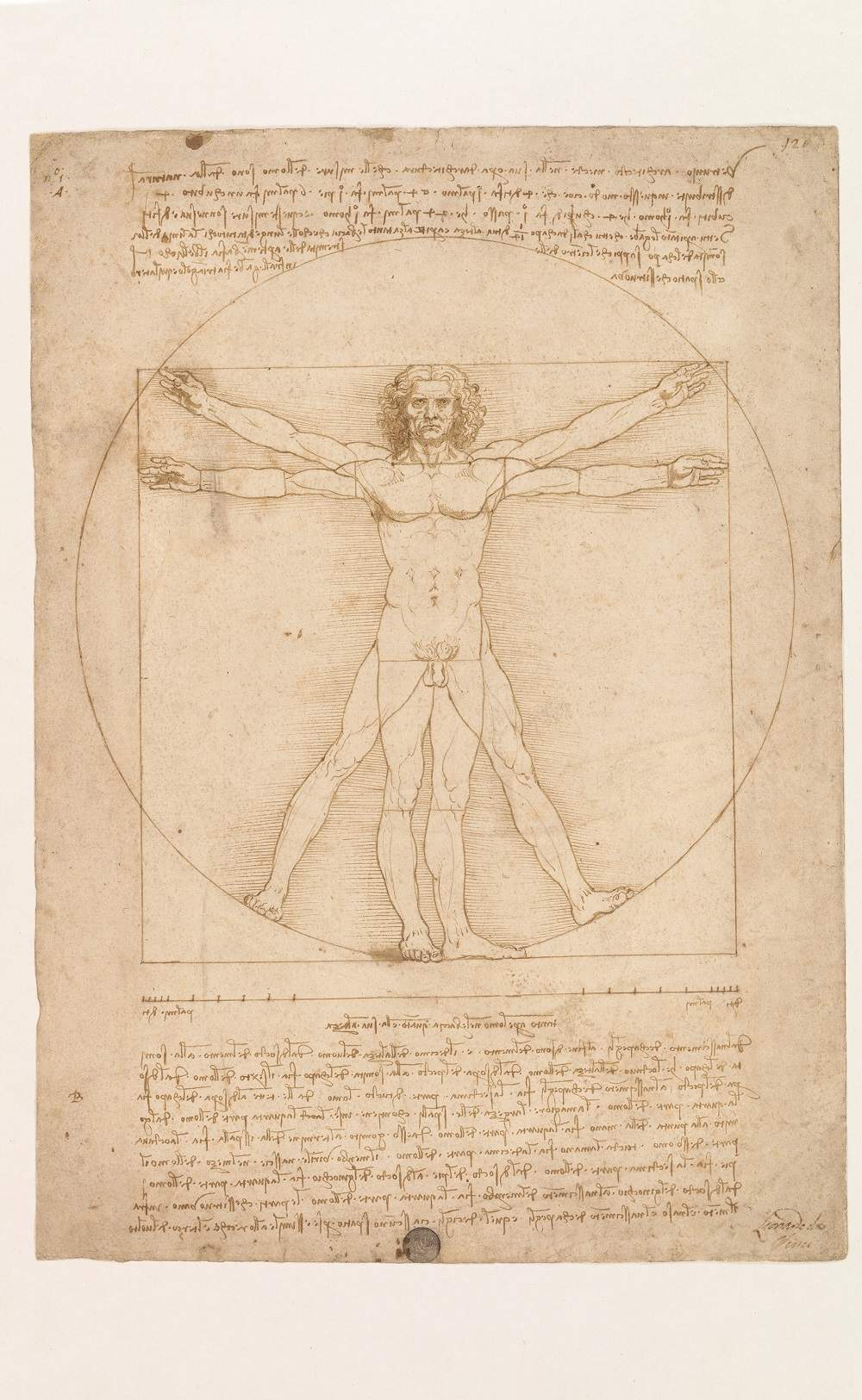

Such scenarios would have triggered an earthquake in the rest of Italy. A cultural “lynching” directed at Minister Dario Franceschini in the 2019 querelle over the loan of the Leonardo to the Louvre. A significant example for the decision by which the Veneto Regional Administrative Court rejected the appeal of Italia Nostra, which had challenged the decision on the loan: beyond the specific case, it also served to mark the boundaries between the field in which politics can move and that which remains the exclusive domain of technicians. The administrative court judges did not, in fact, object to any defect of incompetence on Franceschini’s part in having signed the Memorandum with French counterpart Franck Riester. The minister merely acknowledged decisions and acts taken by his competent technical offices. “In the face of scientific evaluation, which only experts can do, I stop,” Franceschini had commented. In Sicily, however, in the mouth of the assessor the absurd equivalent of that phrase might be this: “in front of my appreciation the scientific assessments made by the experts stop!” Italia Nostra permitting. Faced with an appeal such as that made by this or any other association, the Sicilian Assessor would hardly have found itself subject to it.

To better understand the Sicilian distortions we need once again a comparison with the state framework. We had already dealt with the loan issue at the time of the June 2019 Bonisoli-targeted reorganization. The scenario was then slightly changed a few months later, in December of that same year, by yet another ministerial reorganization. And while this tight rethinking of offices also has its own precedent in the more or less recent history of the Sicilian Department (which has reorganized itself punctually every two/three years since 2010, until the last time in 2019), at the Ministry it is explained by the objective need to adjust the shot of the Reform launched in 2014 on the basis of the criticalities that emerged in the implementation phase, for example for the “museum poles,” now Regional Museum Directorates, weak links in the new arrangement, or to soften the initial clear separation between protection and enhancement, putting the directors of autonomous archaeological parks also in charge of the exercise of the former in the territory of their competence.

For those from Reggio Calabria and up, we checked the procedures with Service II “National Museum System” of the General Directorate of Museums. A distinction must, therefore, be made between “the case in which the works of art and goods requested on loan belong to the state and the case in which they pertain to other territorial entities, but still subject to state protection.” For state property, a further distinction must be made between “property pertaining to museums, archaeological areas and parks, other places of culture of the Regional Museum Directorates and property pertaining to museums with special autonomy. In the former case, authorization for the loan is in the hands of the director of the Regional Directorate of Museums, with preliminary investigation of the merits of the museum, area or archaeological park in which the asset is preserved, after consulting, for loans abroad, the General Directorate of Museums. When the good belongs to an autonomous museum, the act of authorization for the loan is in charge of the director of the autonomous institute, after consultation with the General Directorate of Museums for temporary exhibitions abroad.”

Not unlike the Superintendencies, for autonomous museums, says Simone Verde, director of the Complesso della Pilotta in Parma (from which the Head of a Woman, known as La Scapiliata from the National Gallery, flew right for the Leonardo exhibition at the Louvre), “the director authorizes on the basis of an inquiry prepared by the art historian or archaeologist official depending on the type of good being requested. And to assess conservation aspects, he can rely on the Complex’s in-house ”Restorers" service.

In summary, passing the word back to the General Directorate of Museums, “insofar as it is the exclusive responsibility of the General Directorate of Museums, for all loans on the national territory of goods pertaining to the collections of state museums, whether belonging to the Regional Museums Directorates or autonomous museums, the authorization is in the hands of the directors of the respective offices (Regional Museums Directors or directors of autonomous Institutes). Likewise, for loans abroad, authorization is given by the directors of the facilities (Regional Museums Directors or Directors of the Autonomous Institutes), always after consultation with the General Directorate of Museums.”

In all other cases of loans other than those of goods from state collections, authorized directly by the entities to which they belong, that is, “in the case of so-called ’territory loans,’ that is, works and goods not owned state-owned (of civic museums, diocesan, private museums with usable collections), or in the specific case of the Fec, Fund for Buildings of Worship, of the Ministry of the Interior, the authorization for loans within the national territory is in the hands of the superintendencies by delegation of the Director General of Archaeology Fine Arts and Landscape, pursuant to Circular 29/2019 of the Dir. Gen. ABAP, while the mandatory and binding opinion for requests for exhibitions abroad or in peculiar cases provided for in the same circular is referred to that Directorate General.”

While in Sicily, we said, they have no say in any case, the superintendencies maintain, on the other hand, as we can see, a central role within a volume of movement for loans in Italy and abroad that recorded important numbers until the outbreak of the pandemic: about 9600 works, for a total of 655 exhibitions, for the year 2018; and about 4200 works, for a total of 333 exhibitions, for the first two quarters of 2019.

To fully understand how Sicily makes its own history, one has to delve into the regulatory paths. Regulating loans, even in the island, is the Cultural Heritage Code: art. 48, headed “Authorization for exhibitions and expositions,” and, in the case of extra-national loans, art. 66 (“Temporary exit from the territory of the Republic”) and 67 ("Other cases of temporary exit). But in order to define criteria, procedures and modalities of the loan, Art. 48, c. 3, refers to the issuance of a ministerial decree. It is at this point that the normative references bifurcate. In the state sphere, reference is made to the Ministerial Decree of January 29, 2008 (with Guidelines in the appendix), which has a scientific content, while it is the Dpcm Dec. 2, 2019, No. 169, which defined the latest ministerial arrangement, that indicates in whose head the authorization for lending is referred to. In the Sicilian Region, on the other hand, it is only recently that lending procedures have been regulated, with an assessor’s decree dated that same 2019, which we have already dealt with.

As can be seen, there is no provision in any case for the minister to take over from the technical offices. It is always either the director who gives the okay, after hearing other offices, or the superintendencies. In Sicily, on the other hand, not only is it the Assessore dei Beni Culturali who in fact conditions the authorization, moreover connoted by an excessive centralization, since it is put in the hands of the general manager of the BBCC Department, instead of the individual museum directors, but for the “identity” goods of the Region the entire Government Council is even called upon to express its opinion. Nothing has changed from what we wrote two years ago. Only now the game is getting big because of the Sicilian councillor’s intention to start a new course of international exchanges. On the basis, however, of these bungled assumptions.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.