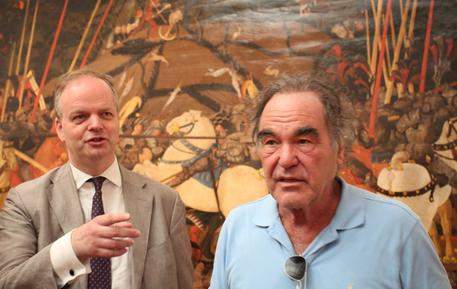

The Uffizi according to Eike Schmidt. End-of-term mega-interview with German director.

Eike Schmidt, director of the Uffizi, will leave after eight years the museum he has directed since 2015. Schmidt, a German from Freiburg im Breisgau, born in 1968, is among the first cohort of directors of autonomous institutes created under the 2015 Franceschini reform. He is thus one of the most experienced directors among those currently leading Italy’s autonomous museums. His figure has often been the focus of attention for many initiatives that the Uffizi has launched over the years. In this interview by Federico Giannini, we talk about many topics: what are the interventions he is most proud of, what is his opinion on the Franceschini reform, what is his position on free admission in museums, the issue of reproduction of cultural heritage, what still needs to be fixed and much more. Here, then, is how Eike Schmidt leaves the Uffizi.

FG. You took over as director of the museum in 2015, you have served two terms at the helm of the Uffizi so after eight years you are leaving a deeply renovated museum. In a nutshell ... how do you leave it in the eyes of those who visit it?

ES. I think the most visible element is the new arrangements, the new museum itineraries that we have brought almost to completion here at the Uffizi: more than 75 rooms that have been renovated or opened for the first time, with whole collections that were not on display or were only on display in a small part, such as Venetian painting of the 16th century that is now articulated in a whole series of rooms, painting of the Counter-Reformation, or self-portraits. Many works that used to be shown in exhibitions like “The Never Seen” are now permanently on view. So if I had to summarize one sentence, I would say that the Uffizi is a museum where you can see well-known and beloved paintings and sculptures again, but in a much quieter atmosphere, without getting elbowed by the neighbors; but at the same time it is also a museum that now offers so many discoveries. Even works that were on display before are seen differently, because we have redone the whole lighting system: when perhaps people will no longer remember my name or that of architect Antonio Godoli however people will probably say that the centuries-old problem that travelers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and again of the twentieth century were already complaining about, which is that the Uffizi has a fantastic collection but you can’t see anything because of the lack of proper lighting, has been solved. Thanks to the lighting we have now you can see, for example, even the landscape behind theEleonora of Toledo by Bronzino, you can see all the details of the famous paintings and those to be discovered-this is perhaps the most important and obvious part of the changes made.

Of all that has happened since you have been director, what is the aspect, activity, or novelty that you are most proud of?

There are many, but one is definitely the fact that we have finally, and systematically, stabilized accessibility-that is, the possibility of visiting and enjoying the museum for those with motor, sensory, cognitive, and emotional impairments-by founding a special department. Accessibility is no longer just “niche” service that is offered extra, for people with disabilities, but is the key that all of us, including the able-bodied, need to be able to appreciate the collections: it is something that affects the visit in a substantial way. Thanks to this department we also do a lot of initiatives for types of disabilities that are not even that well known to the general public: in addition to motor and sensory disabilities there are also cognitive and emotional ones, all the way to the universe of neurodiversity where the emphasis is really on diversity. For the first time we conceive and produce tactile books, for the blind and sighted together, we give Italian Sign Language courses to our officials and assistants, and so on. There’s a whole series of activities, but it’s part of a larger, more complex system that really is about access for all of us to works of art. Basically, accessibility is not just a matter of rotell chairs: it’s also, to name just one, about making our captions more readable, both through the use of a correct font and the language used. And then the signage in general.

Is there anything instead that you would have liked to do and did not do?

The Vasari Corridor: I wasn’t able to open it for the 30th anniversary of the Georgofili massacre, and that really made me very angry. It’s nobody’s fault in particular, in the sense that we started the work at the end of 2021, but there were so many reasons why, after the Corridor was closed, very unexpectedly, overnight by the Fire Department in 2016, we still took the time to present, for the first time, a final (and then immediately afterwards executive) project and to find the money. Also with the Fire Department, we studied the future operation of the new Vasari Corridor, which must be brought in line with the regulations. In parallel we commissioned and started the work. But then when the construction site was open, static problems emerged, both in correspondence with the area affected by the 1993 bomb and also in correspondence with the area that suffered the great explosions of 1944, so there the culprits could only be Cosa Nostra and the Nazi Wehrmacht. However, we also found something good and beautiful, namely, in a way that was not expected or predictable, the original Vasari floor. So there were good and necessary reasons that slowed down the restoration work. The only thing that I don’t care about is whether I will be present when it is opened: of course I would be grateful if they invited me to the opening, but if for some reason I could not attend it doesn’t matter, there will be another director to open the Vasariano, and I’m sincerely fine with that. What I’m not perfectly fine with is that it would have been a nice symbolic thing to be able to reopen for the 30th anniversary.

The setting up of

The setting up of The setting up of

The setting up of

You were one of the first directors to enter under the Franceschini reform, and the time is now ripe for a judgment on a measure that has revolutionized the world of state museums in Italy. What is your opinion of the Franceschini reform? What has worked, what has not worked, what needs to be revised...? ?

The Franceschini reform certainly worked, as is confirmed by the very fact that now a government of a completely different political orientation is carrying it out. In particular, the reform has worked in the three areas of autonomy, namely the scientific autonomy of museums (to which one should add artistic autonomy, because the closer one gets to contemporary art, the less it becomes a purely scientific choice), then organizational autonomy, and then, most important of all, budgetary autonomy, because it makes museums more responsible, in the sense that if a peripheral office of the state is responsible for its own revenues then it can also plan and say “if I make these revenues the next year or two years from now I will have enough money to be able to spend them on a project that I care about.” After all, we who live and work in the field every day know the priorities much better than those who are in a central office at the ministry, in front of the desk. What has been missing and is still missing is the autonomy of human resources. Personally, I am not convinced that this autonomy should be total as in a foundation (it would be the simplest but also the most trivial solution to the problem), but we could also think of models in which the peripheral offices have some say, or in which the central offices are given more incentive to make inspections, to analyze the actual needs and not to draw them at the desk, with the result that, as we know, often the staffing allocations do not meet the real needs. I say this for a very specific reason, because I see a huge advantage in the systematic work of an entire ministry: in the superintendence officials, for example, there is still a knowledge, even methodological knowledge, that can only be gained by working on the ground, with churches, with private collections and so on. In fact, I am pushing Uffizi officials to serve at least one or two days a week for one of the neighboring superintendencies, because it is experience that cannot be accumulated in any other way. Conversely, I have also always been open and grateful to have superintendency officials at the Uffizi, one or two days a week, a procedure that has worked very well with some colleagues. We have collaborated or are collaborating in this way with the Superintendencies of Florence, Bologna to Pisa. Unfortunately, there are also Superintendents who unfortunately do not accept this kind of “osmosis.” Instead, it would be to be hoped for a norm that rewards officials who between superintendencies and museums collaborate a few days a week. This is a very, very useful dialogue for everyone. Let’s also think about the export office: since the beginning of my tenure, with then-Superintendent Andrea Pessina we established that the art historians and archaeologists of the Uffizi all work there in weekly commissions. Now moreover, one of our officials is also deputy director of the export office. Maybe it’s because of my experience as a director at Sotheby’s, but I judge the service at the export office as crucial for the curators so that they can deal with the movements of the art market, and every now and then this allows us to bring home a nice catch for the museum.

Here, on this very point, some of your colleagues have identified as one of the weaknesses of the reform the fact that museums cannot manage staff independently. A few years ago, for example, Peter Aufreiter, who headed the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche at the time and was at the end of his term, told me in an interview that the problem lies precisely not only in the excesses of bureaucracy, but also in the lack of flexibility that autonomous museums have on staffing (and I think that’s why he decided to leave Italy). In your opinion, should museums be autonomous in this regard as well?

I fully agree. At least partial autonomy over human resources should be added to what is already there (i.e. economic and budget autonomy, internal organization autonomy, and scientific and artistic autonomy). Meanwhile, to triangulate the problem, we have worked on three points. The first is the remansions: by happy coincidence with the special autonomy of museums, there came a series of decisions by judges confirming that it is not okay to put people who have won competitions as museum assistants (and who therefore also have scientific, educational, curatorial tasks) simply as guards in the halls. So there was a great opportunity to remodel these colleagues, often with PhDs and other very high qualifications, by integrating them into existing offices and to establish new ones such as, for example, the department for accessibility and cultural mediation, or the department for digital strategies. Even, the human resources office lacked ... human resources. And it was only thanks to the reshuffles that we were able to start working at full speed again. Before, it was a disaster because they were struggling and even risked not being able to respond to Ministry circulars due to lack of staff. The second point is Ales: thanks to the hiring of the in-house company, which is paid for by the museum since it has partial autonomy, we were able to partially supplement human resources and also create 120 new jobs. With the arrival of autonomy came an end to the long era in which, with great pomp and celebration, we would open some new hall or exhibition, and then two weeks later close again because there was no staff to keep the spaces open. Since 2016 we have managed to keep all the Uffizi rooms open, even on weekends, and also to have guards for the many new rooms we have restored and opened. Unfortunately, the problem remains, because the units of the in-house company are supposed to be used only temporarily, pending state hiring. For a number of years not only did the competitions for state positions not start, even hiring through Ales was blocked, and we were not able to grow as we would have liked. This is a problem that will have to be solved at the central level. The third point is the “post-quiescence” volunteers. More than a dozen officials who have retired are serving voluntarily, without being paid (beyond their pension, of course). They are truly invaluable resources: among them is also a lieutenant of the Carabinieri who retired and now, every day, comes here and works for us also as a trait d ’union with the various forces of the Arma with which we have a very close collaboration. Our lieutenant, from the height of his many years of experience in the field, offers us suggestions and advice on the safety of both the works and also man-made safety within the museum, or when we do exhibitions elsewhere he checks, he establishes lists of activities that need to be done to adapt safety. These are experiences that are in addition to the technical experiences of our officials, though without replacing them. It also applies to former art historian officials, for example, who are active and are loved by those still in service because they take on projects and initiatives that they could not do because they do not have enough time or specific experience. They often have uncommon skills-I think of Anna Maria Petrioli Tofani, the historical director in the year of the Georgofili Massacre who coordinated heritage preservation at the time. Now that I have reactivated her, she works practically every day in the Cabinet of Drawings and Prints always in her field of academic specialization. She is currently cataloging all the donations from the 1980s and 1990s.

Closely related to this issue is that of economic management. A few days ago his colleague Christian Greco from the Egyptian Museum put forward the idea of making his museum free, for everyone, in a few years. This is a much debated issue, and I wanted to ask you if you agree with this position, and especially if Italian museums can afford free for all.

I really respect my colleague Greco, but to both questions my answer is negative. Free admission as a general rule is an entirely ideological issue, not a practical one. The cost of the ticket often has a management function as well: to give an example, at the Uffizi it has been very helpful to be able to introduce an early morning discount. Those who arrive before 9 a.m. save 6 euros, and this incentive has resulted in more visitors in the first hour, freeing up space for those arriving later in the day. In reality, in a situation of high demand pressure, which often exceeds supply capacity, management falls back to a primitive, archaic form if it lacks the regularizing cog of price and reservation. With total free admission for all and at all hours, first-come, first-served enters first, second-come has to wait, and those who arrive after 10 a.m. may not enter the museum at all. The right of the fittest, the most tenacious, prevails, and in a single day hundreds of thousands of precious hours of people’s lives are thrown away, who instead have to stand in line with great boredom. Non-management of gratuitousness also always encourages petty crime, secondary ticketing for payment even when the ticket itself is free, “line hopping” for those who have some acquaintances among the ticket controllers, or simply someone who stands in line for others. We know this even from concerts and sporting events. This is true for museums like the Uffizi or the Vatican Museums, where demand exceeds supply. Instead, for museums that have little demand, free admission can be a very useful tool, especially if used in a promotional logic and for certain demographic goals, for example, free admission for citizens or for young people. The latter is already there until the age of 18, a much higher age than in many other international museums. In addition, state museums currently offer 15 days a year of free admission for everyone. However, it should be made very clear that total and universal free admission is not economically sustainable. It costs money to produce art, but it also costs money to protect, restore, research, communicate and protect art. We often talk about free in British museums, but it is a fiction: in about 20 British state museums the permanent collection is free, instead to see an exhibition you pay, and much more than in Italy. Most English museums charge a fee, and admission costs more than in Italian museums. A very interesting finding is the fact that free museums have declining visitors, while the number of visitors to paid museums is growing. The connection between free admission and accessibility is in fact very tenuous, and in many cases nonexistent. Not coincidentally, Paola D’Agostino has put at 23 euros the ticket for just the room with drawings attributed to Michelangelo and followers in San Lorenzo, and I think the visit is already sold-out for quite some time.

Eike

Eike

However, some might object that 25 euros to enter the Uffizi is not cheap. Are you thinking of introducing other discounts in addition to the existing ones?

Within a budget of a family or an individual interested in culture, where it has to be compared with spending on music events, sports, books, magazines, clothing, a night out at a restaurant, etc., even the ceiling price of admission to the Uffizi, which is currently equivalent to 25 euros in high season, is objectively very low. However, there are many ways to still spend much less. With a minimum of patience and planning one’s life, anyone can enter the Uffizi for free as many as 15 days a year. Those who come in low season pay less than half. Those who get up early in high season receive a discount of 6 euros. For true enthusiasts (who are not students or scholars of art history or archaeology, who get in for free anyway), there is the Passepartout annual pass that is valid 365 days from the date of first use, at 70 euros in the individual version, and 100 euros for families. The annual pass not only includes unlimited admission to the Uffizi, the Pitti Palace, the Boboli Gardens, the Museum of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, and the National Archaeological Museum of Florence, but also priority admission. It is the only ticket that truly cuts through the lines.

The Uffizi, however, can afford to pay its staff, to function and to operate other museums as well (remember that 20 percent of the income goes to the solidarity fund that is used to run the smaller, less wealthy museums), partly because they have significant income that comes from their two million visitors a year who, for the most part at least, come in and pay a ticket. So ticketing is a significant source of revenue for museums, right?

That’s exactly right. This year the Uffizi will provide an aid to “poor” museums of about 10 million!

Eight years after the museum reform, there are five museums and archaeological sites that not only manage to be self-financing, but also produce something extra that serves both to finance other, less fruitful museums and to be able to invest in strategic projects to improve their own reality. We have now reached a point where we could (and in my opinion should) raise the solidarity fund’s share to 25 percent or 30 percent of ticketing revenue, to give more and more museums the opportunity to develop models of self-responsibility and management with a significant portion of self-generated funds (considering the contributions to the Archaeological Museum and the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, the Uffizi is already at 24 percent). Of the 490 state museums, if managed well surely more than a third could in the medium term reach self-financing. We also need to think about consolidation of museum entities, such as that of the dozen or so museums that have been merged into the Uffizi Galleries, or now the annexation of the Gallerie dell’Accademia to the Bargello Museums. With these groupings, within the next decade more than half of the state museums will be able to be self-financing. For the others that remain, probably the best route would be to assign them to municipalities (often small towns) that could put them in synergy with their museums and other local cultural institutions. How come we cannot raise the solidarity contribution to 50 percent? The answer is very simple: extraordinary maintenance and retrofitting of buildings, infrastructure have been procrastinated for decades, and it will still take years to achieve the necessary goals. As we have seen over these eight years, the best way for us to solve this problem is to give individual museums the responsibility to identify problems and solve them. This is one of the great advantages of economic autonomy for museums.

By the way, this redistribution, if you want to call it that, the Uffizi has done it not only with the 20 percent to which the state obligates the museum, but also with a project such as the Uffizi Diffusi: there is no need to go over the history of the project today, on which we have already talked about in another interview, but a question about Uffizi Diffusi I want to ask him anyway: what are you leaving in the hands of your successor and what suggestions do you have for him to continue this project?

Uffizi Diffusi has gotten off to an even better start than I dared hope, and it has developed such a dynamic that surely whoever may succeed me will continue on this path. With more than 40 projects in Tuscany already implemented, a few weeks ago we added the third project outside the regional borders, albeit by a few kilometers: after Ravenna and Assisi we brought the Uffizi Diffusi to Faenza, with a very concrete connection to the place since in this case the subject of Pietro Lorenzetti’s polyptych, Santa Umiltà di Faenza, today the patron saint of the city, historically traveled from Faenza to Florence and established a monastic community on the banks of the Arno as well. Adding to the historical bond between the two cities, which continued into the 15th century, is the solidarity over the flood. In fact, one of the panels of the polyptych depicts Blessed Humility walking above the Lamone, the river that flooded. This exhibition is truly an example of all the principles of Uffizi Diffusi. What’s more, the museums involved are doing visitor numbers they didn’t have before. These are all unique exhibitions for unique places that are already full of art, however, but people don’t usually visit them: they go there because they are attracted by the Uffizi Diffusi initiative and also discover what is already there.

Uffizi Diffusi also allows me to ask a question about the relationship with local communities. A few days ago on Finestre Sull’Arte we hosted a contribution by your colleague Francesca Rossi, director of the Civic Museums of Verona, who spoke on the topic of the relationship between museums and local communities. Francesca Rossi wrote that one of the main problems of museums, always in relation to local communities, is to “develop new participatory models of management in order to conquer a new space in society, where they can be perceived as engines of humanity’s journey, repositories of individual and collective memory in a broad sense, local and global, for the construction of the civilization of the future.” How have the Uffizi approached this problem thinking about the fact that they are a museum that has (we said it before) a strong tourist pressure and still remains the great museum of a great city?

At the ticketing level, the annual PassePartout subscription, in which more than 10,000 people already participate. But that’s not enough. I’m thinking of the lectures, which we offer free to all citizens every Wednesday afternoon at 5 p.m.; the many opportunities for study and insight on the website and various social channels; and above all, the educational programs for families and schools.

During the lockdown, when children were at home, we offered about 600 “virtual school field trips” to classes, with customized and non-standard connections. It was an almost heroic feat by our department, but imagine what this contact, this outstretched hand from outside, this escape into art, meant to teachers and children locked in. In the last eight years we have replenished the resources of our Education department, which together with the Brera department was the first in Italy (it was founded in November 1970) and which throughout the 1970s functioned very well. At the time there was great optimism and it was expected that within a few years all museums would be equipped with an “educational service,” as it was called at the time. But museum education suffered its first hard blow in 1982, when the House and Senate rejected a bill that would have established the professional figure of the museum educator. This rejection was completely at odds with what was happening in the rest of Europe and even in the United States. From that moment on, unfortunately, the crisis of educational services began. During the 1980s, in fact, the human and economic resources that were needed for proper functioning were taken away from this sector: a progressive and prolonged erosion over time, corresponding to a policy oriented more and more toward tourism at the expense of the education of young citizens. Suddenly, education was seen as something dispensable and, if anything, added, and not substantive. Still in the 2004 Urbani Code, educational services are counted among the “additional” services to be given in concession to private individuals. Now we provide hundreds of thousands of euros each year to hire specialized and experienced museum educators. These are freelancers. I see nothing wrong with parents contributing a few euros per child for visits, but we also have programs for those who cannot afford even that, and those for schools are heavily subsidized by us. It is even more important for kids and toddlers than for adults that the activities take place interactively and in small groups. Unfortunately, in recent years we are experiencing a great crisis in the school system, in Italy as well as in other European nations. We certainly cannot replace the schools, but we can make a fundamental contribution, with a lifelong effect, that is. Our “Art Ambassadors” program, whereby high school kids learn art history for a year and then act as guides for two weeks, including in foreign languages, has also proved to be very important from the point of view of personality development, because it is often on this occasion that young people teach adults something, and understand that they have arrived at the same level.

Earlier en passant you talked about acquisitions: can you tell us what you think is the most important one that the Uffizi has made under your management?

The most important acquisition is always the next one! However, among the acquisitions I could mention the two paintings by Daniele da Volterra from the Pannocchieschi d’Elci collection, which had always remained with the artist’s heirs. I am also very proud to have restarted, together with curator Elena Marconi and the Acquisitions Committee of the Gallery of Modern Art and our Board of Directors, the enrichment of great Italian Romantic painting, from Hayez to Bezzuoli. Of the latter we were able to purchase as many as eight paintings for the Pitti Palace, and we deepened our knowledge of the artist through a major exhibition.

Uffizi Diffusi in

Uffizi Diffusi in Uffizi Diffusi

Uffizi DiffusiAnd again en passant we said that the Uffizi is under great pressure. Let’s broaden the argument: the Uffizi is now a museum complex of more than 2 million visitors and helps move a significant part of tourism to Florence. Tourism in Florence that is an asset but also a problem, how do you think it is managed?

As the Uffizi Galleries (with visitor numbers expected to exceed 5 million this year for the first time, more than half of them in the Statues and Paintings Gallery) we obviously act in a broader context, a local, regional, national and international context. We have seen that through direct discussion, for example with hoteliers, but also with tour guides, with whom we meet regularly, we have been able to understand and address a whole range of issues but also opportunities that we would otherwise have struggled to identify on our own. It is essential to talk directly with the business community. We are aware that few other museums do this. There are still those who say, “We are the state, they are private, we have nothing to say to each other.” This is wrong. At the political level, as is well known, we are collaborating very positively and frequently with the Region of Tuscany on “Uffizi Diffusi,” thanks in part to President Eugenio Giani’s personal passion for local and regional art and history. I have also regularly made myself available to the Culture Commission of the Florence City Council. I have invited the commission several times to the museum for site visits, to explain our strategies and for updates on our many projects, but also simply to answer their questions.

Recently the Uffizi has found itself at the center of the discussion about the image of Venus being used for the Ministry of Tourism’s campaign. I won’t ask you what you think about that campaign, because the interesting topic is another, namely the use that is made of images of cultural heritage, about which likewise there has been so much discussion in recent weeks and which continues to be discussed; moreover, the topic will be the focus of the next issue of our print magazine. I’ll come straight to the point: do you think there is an image right on cultural property, and therefore works should be protected from purposes that have little or nothing to do with art, or should we move in the direction of liberalization along the lines of what so many American museums do, for example the Metropolitan?

In the meantime, it should be considered that there are huge differences as far as laws are concerned: situations are very different between states that rely more directly on Roman law, and those that have instead constructed their law based on the accumulation of individual cases decided by judges, that is, the Anglo-Saxon tradition in particular. The United States of America, England but also Holland tend to completely liberalize the use of images in their museums, and in those countries it is difficult to justify a public right of images. In France, Spain, Italy and even Greece and Germany it is different. In systems of the Roman law tradition, art is not considered just any object, marketable without limits, like a bicycle, a monitor or anything else, but it is considered a cultural good, that is, an object that never belongs to the individual alone but also to the community. Publicly owned cultural goods are res extra commercium. This fact also determines the derivative use of the cultural good. At this moment in history we are seeing great technological revolutions in the reproduction but also in the computerized recomposition of images, and this is causing new laws to be born all over the world to regulate these phenomena. It is difficult to predict what the prevailing solution will be from a legal point of view, and whether there really can be a universal or at least predominant solution in international law. However, I would like to emphasize how much the Italian norm protecting the purposes of free expression of thought, educational or even promotional purposes (although the meaning must be specified) is in truth very good, compared to those of other countries. As in the case of free access to museums, great care must be taken in the case of liberalization of image rights, because free use is by no means equivalent to accessibility to all. If our ideal is the accessibility of works of art, total liberalization might seem the easiest solution, but in fact it is not. We see this already now with photographs from large agencies, which charge 600 euros or even more just to download and view an image. The more images there are, the more important (and necessary) the intermediary, platform, catalog, or algorithm that connects the user with the image becomes. Upstream liberalization per se does not guarantee improved accessibility at all if it is not accompanied by legislation that also guarantees it downstream for specific purposes.

Before we head to the conclusion--any suggestions to give to your successor?

I will give them to the successor at the time, if he would like to hear them. It’s only fair that everyone comes with their own perspectives, and new ideas and great strength in putting them into practice are also needed to continue and increase the big projects that have been started such as the “Uffizi diffuse” and “Boboli 2030.”

Clear. So I ask you in one line: where will we have the pleasure of seeing you once your tenure at the Uffizi is over?

Apart from on the pages of Finestre Sull’Arte, on which I hope to continue to see myself, my home is here in Florence and I maintain it, I am not planning any move. Of course professionally I could also be active in another city, but that of course is not up to me alone.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.