Van Gogh exhibition in Milan, why yes and why no: double review

Why yes. Federico Giannini

The mythographies that hover around the figure of Vincent van Gogh have long prevented the exhibition occasions dedicated to him from delving into the intricate complexity of his figure, far removed from that idea of the out-of-the-ordinary genius, mad and moved only by his pure feeling, to which the frivolities of the vulgate have always accustomed us. A talented painter yes, a disturbed man also, and also with a soul torn apart by irremediable torments: one need only read his letters to realize this. Yet, from reading what Van Gogh wrote to his loved ones (few artists wrote as much as the Dutchman, and his letters are an invaluable source for reconstructing not only his character, but also his artistic choices), there also emerges theimage of a man who was perfectly aware of what he was doing, a man full of passion and passions, a man who was anything but detached from the reality around him, a man with a vast culture and a strong interest in reading. That is why an exhibition such as Vincent van Gogh. Educated Painter, the exhibition that until January 28 occupies part of the rooms of Mudec in Milan, can be welcomed, indeed: it can be said to be a necessary exhibition.

Of course: it will be said that the material is essentially the same that innervated last year’s exhibition at Palazzo Bonaparte in Rome. It certainly could not be otherwise, since the Mudec exhibition is also organized with a block of works loaned by the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, which has by now accustomed us to this modus operandi: their collection holds dozens of Van Gogh’s works, so every now and then they lend a selection to some museum around the world, and it just so happens that in the past year it has twice been Italy’s turn. Yet despite the fact that Rome and Milan went to almost the same works, two completely different exhibitions have resulted. In Rome, with the exhibition curated by Maria Teresa Benedetti and Francesca Villanti, there was a chronological, agile, accurate and in-depth itinerary on Van Gogh, aimed at giving an account above all of his formal choices, without, however, neglecting the motives that supported them. In Milan, on the other hand, the exhibition curated by Francesco Poli, Mariella Guzzoni and Aurora Canepari turns its gaze to Van Gogh’s profound culture, the books he read, the trends he observed, looking for their feedback in figurative texts.

For those familiar with Van Gogh’s art, of course, the exhibition introduces nothing new. And we are not just talking about insiders: even an enthusiast who has not just visited a few mediocre exhibitions (such as the 2017 one in Vicenza), but has read a few books or articles about Van Gogh, will not find anything in the Mudec halls that he or she does not already know. One can, however, get away for a moment from the idea that exhibitions should only serve to present news to those who are already informed about the subject: if one imagines an exhibition that can break down the stereotypes around one of the artists most beloved by the general public, an exhibition that contributes to increasing everyone’s knowledge about him, an exhibition that succeeds in providing visitors with a more correct reading of the subject it deals with, then, even in the absence of substantial novelty, the museum hosting it will have been right to organize it.

“Recently,” Van Gogh wrote in a letter sent to his brother Theo on December 23, 1881, "I have been reading Michelet, La femme, la religion et le prêtre. Books like these are full of reality, but what is more real than reality itself, and what has more life than life itself? And we who do our best to live, why don’t we live even more!“ And even earlier, again to his brother, on November 19: ”For my part, père Michelet does me much good. Still read L’amour and La femme and, if you can get it, Beecher Stowe’s My wife and I and Our neighbours. Or Jane Eyre and Shirley by Currer Bell. Those people can tell you a lot more things much more clearly than I can.“ In his letters, Van Gogh talks about the books he reads, comments on them, recounts the insights they provide him. In the early 1980s, his interests are directed primarily toward socially engaged literature, and the first part of the tour itinerary displays paintings and drawings in which ”visual" traces, so to speak, of his readings can be found. Jules Michelet’s History of the French Revolution is one of the reasons why Van Gogh felt a strong closeness to the peasants of the Borinage, a poor rural region of Wallonia where the artist was between 1879 and 1880 to conduct activities as a preacher (at that time his activity as an artist had not yet begun). His readings, moreover, also opened up new religious ideas for him, and it was the maturing of these convictions that aroused his artistic will (in a letter to Theo, for example, he goes so far as to say that he saw in Jules Michelet and Harriet Beecher Stowe two continuers of the Gospel: “Take Michelet and Beecher Stowe, they don’t say that the Gospel is no longer valid, but they help us understand how applicable it is to this day and age, to this life of ours, for you, for example, and for me, just to name someone. Michelet even says fully and aloud things that the Gospel simply whispers to us in a germinal way, and Stowe goes as far as Michelet does.”) The exhibition illustrates this transition well: Michelet and Beecher Stowe are the main inspirers in literature, while in art Van Gogh finds a kind of ideal mentor in Millet, whom he takes to copying relentlessly (early drawings copying works by the great French painter are displayed in the first room).

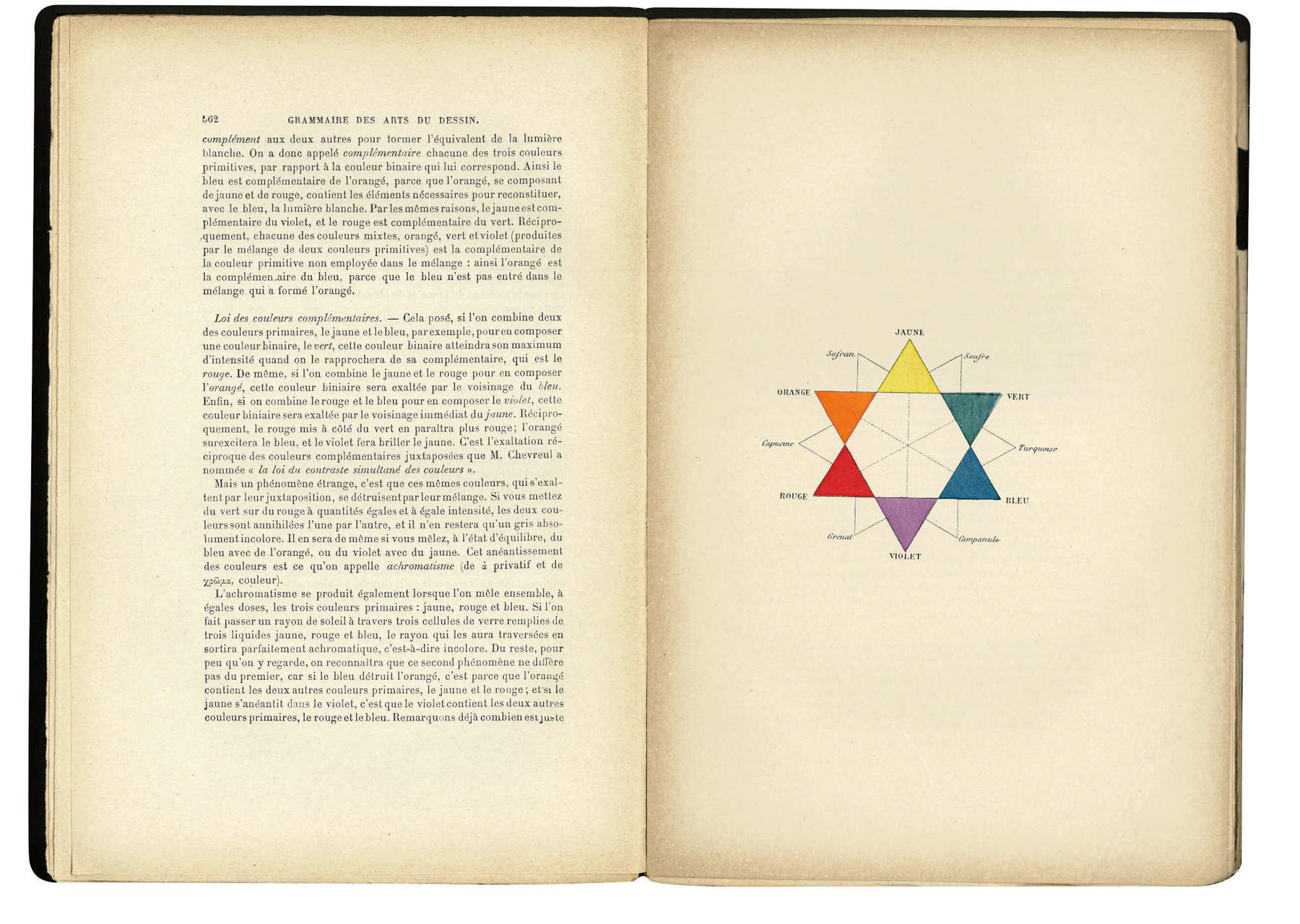

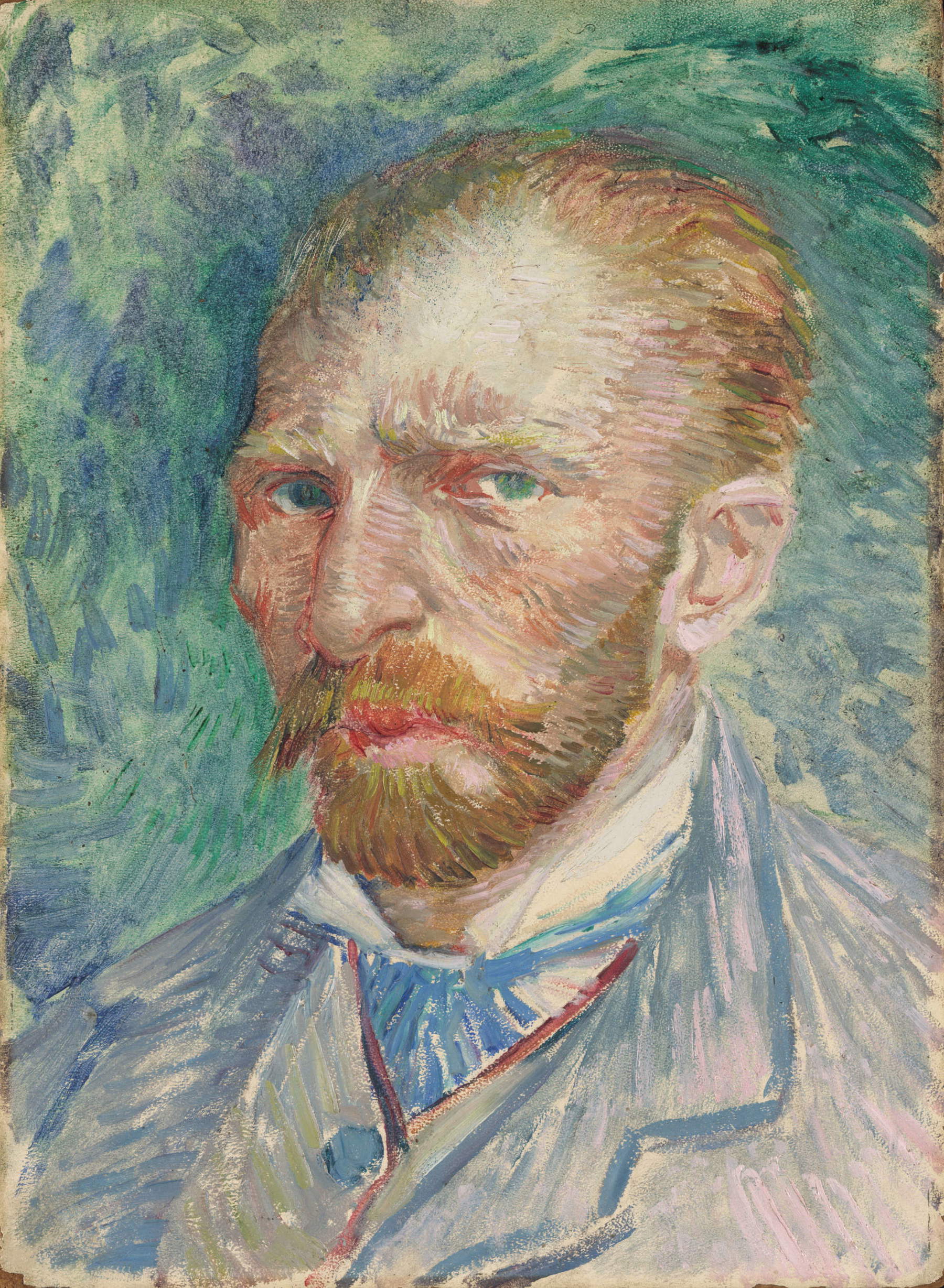

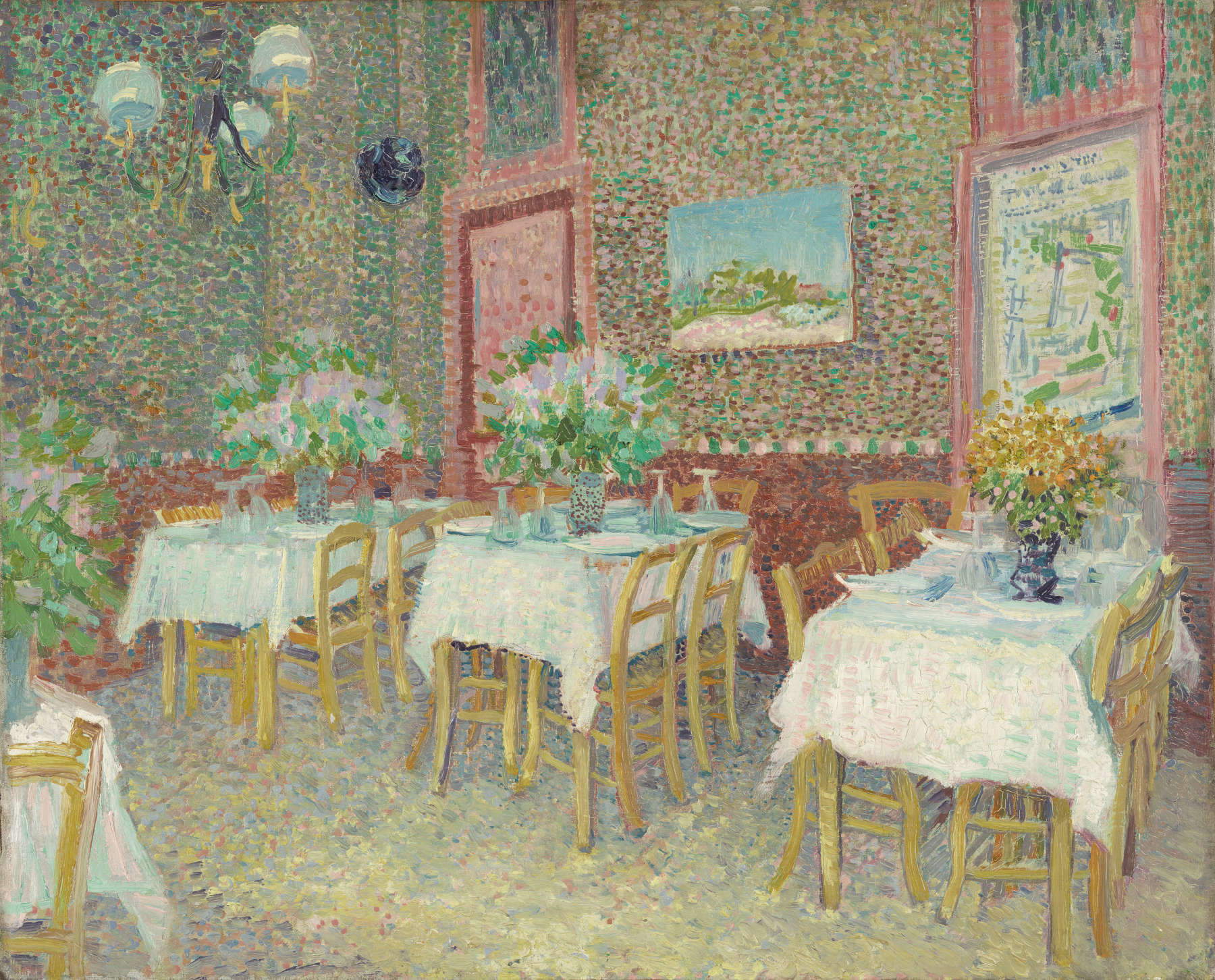

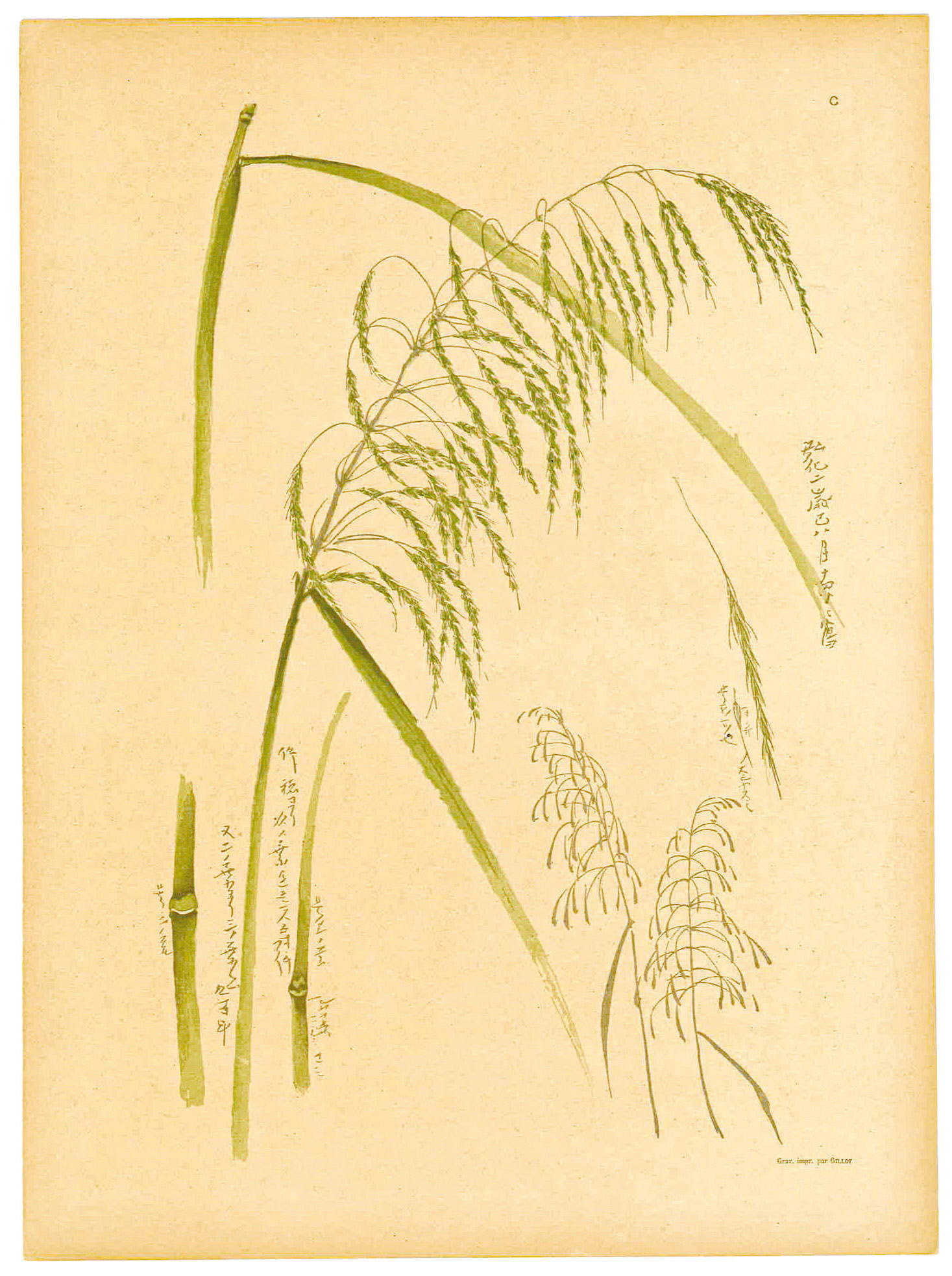

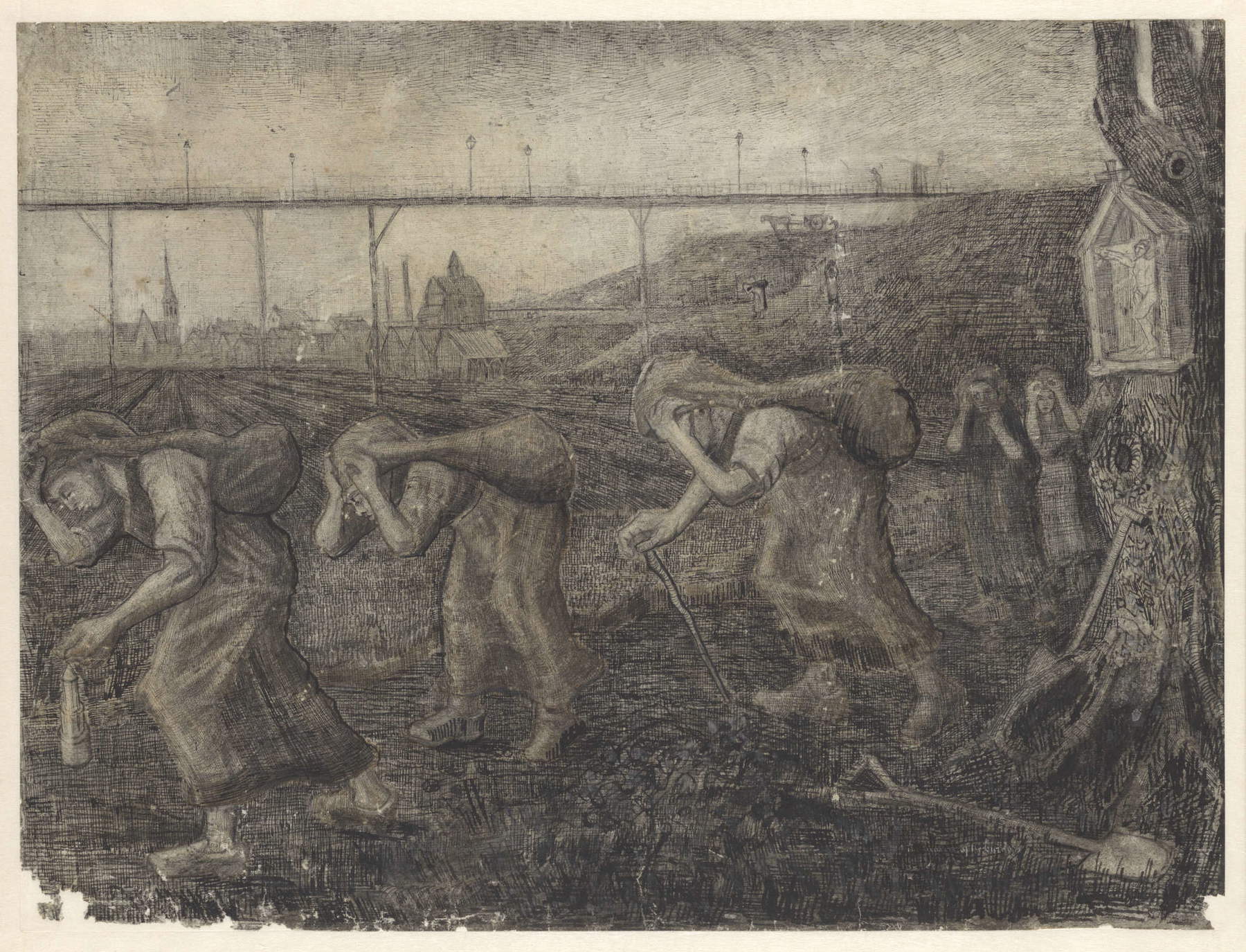

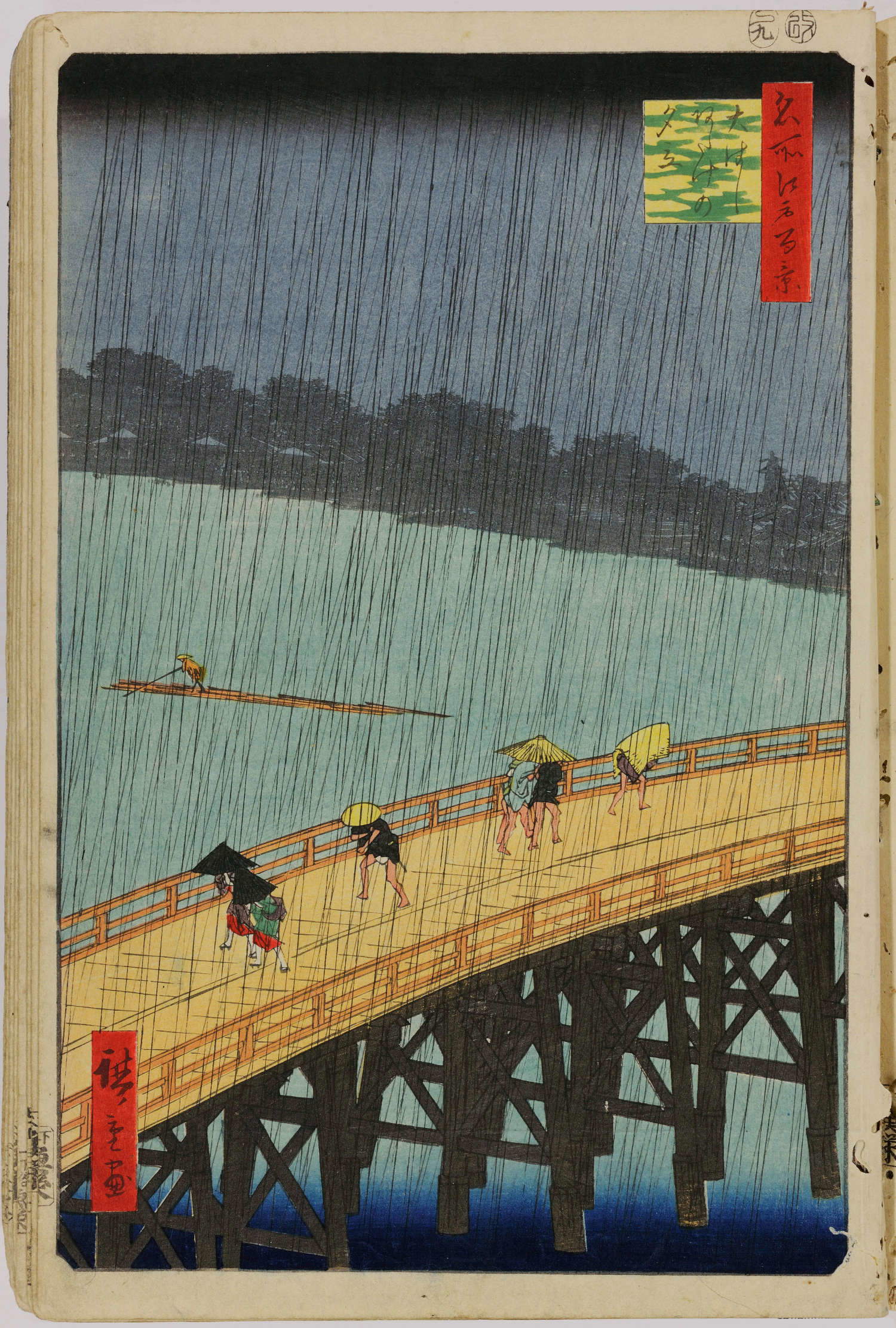

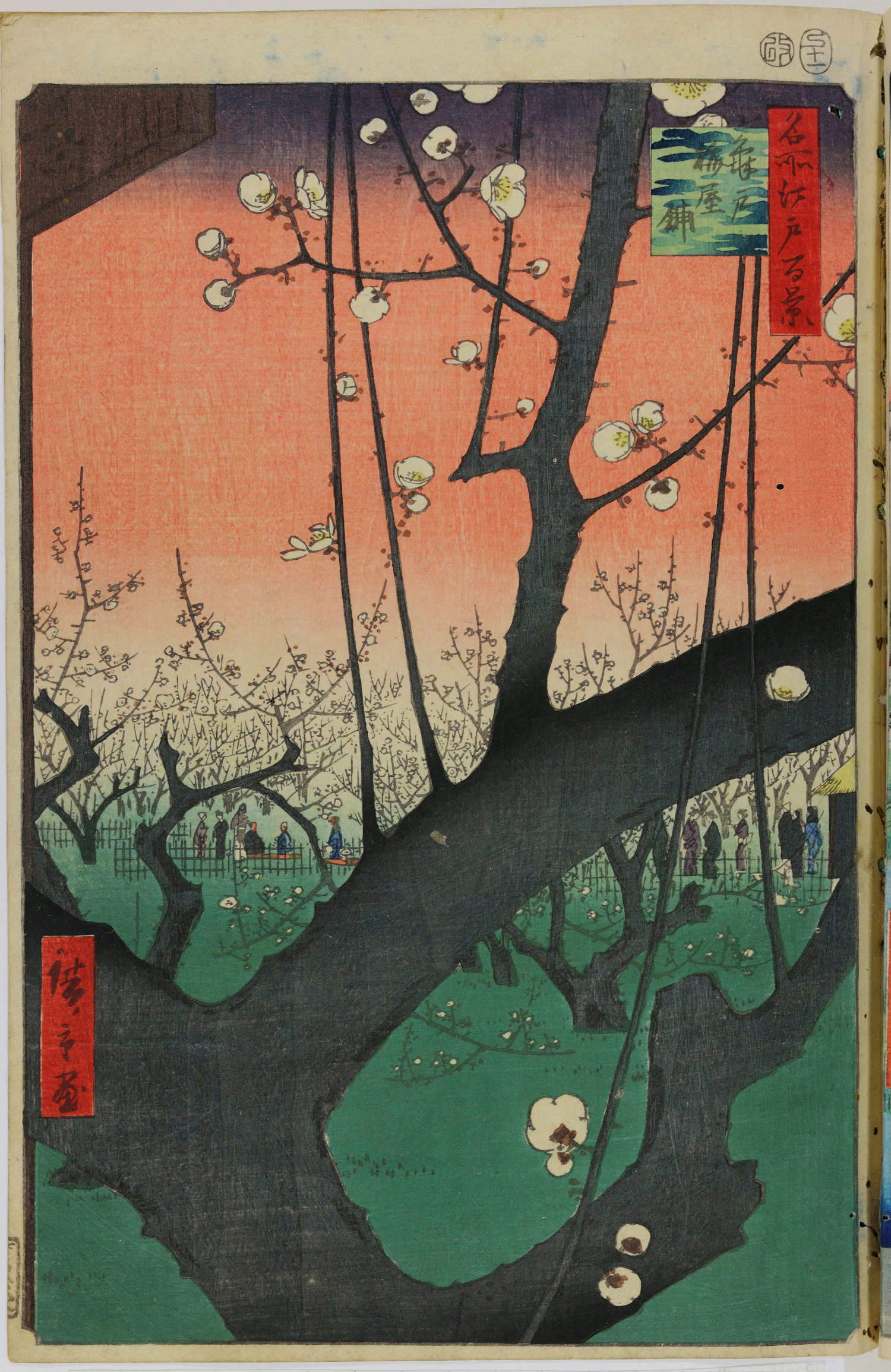

The “realist” approach that characterized Van Gogh’s work until his move to Paris is also affected by the reading of Émile Zola’s almost complete output: echoes can be felt in the drawings depicting workers and peasants or in those capturing factory interiors and workshops. But there are also precise cross-references between art and literature: the chapter on the nest in Michelet’s L’Oiseau finds its visual counterpart in Van Gogh’s Nest (the artist kept, moreover, a collection of birds’ nests, creatures he considered equal to artists: more generally, his love of nature had never waned, nor would it in the course of his career). The stay in Paris, which lasted from 1886 to 1888, signified Van Gogh’s acquaintance with Impressionist painting: the exhibition anticipates this passage by giving visitors an account of how, during his time in Nuenen (between 1883 and 1885), the painter had studied in depth and systematically Charles Blanc’s Grammaire des Arts du Dessin and his theory of color, a reading that would come in handy when he began to frequent the various Tolouse-Lautrec, Bernard, Signac (with Bernard and Signac he also found himself painting together, and as can be seen from the sequence of paintings the exhibition presents at this point in the itinerary, from theSelf-Portrait that marks a sort of caesura between the first and second part of the itinerary, to the Landscape of Paris as seen from Montmartre via the ever-present Interior of a Restaurant, the proximity to Signac is such that in the first months of his Parisian sojourn Van Gogh quickly assimilated his technique). Paris opened up further, new interests for Van Gogh: these were the years in which the artist developed his passion for Japanese art, known through the magazines that were being published at the time in the French capital, starting with Le Japon Artistique, which brought Van Gogh to learn about the art of Hokusai and the other greatukiyo-e artists; Van Gogh himself would become a collector of Japanese prints and his art would be profoundly affected. Missing from the exhibition are two cornerstones such as Bridge in the Rain and Plum Blossom, both from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, but there is an Orchard Surrounded by Cypress Tre es displayed next to some prints on loan from the Chiossone Museum in Genoa, which is irrevocably affected by this new interest, as are Willows at Sunset , which well convey the ’idea that a Japanese artist, as Van Gogh would have written, studies “a single blade of grass,” but “that blade of grass leads him to draw all the plants, then the seasons, the grandiose aspects of the landscapes, then the animals, and finally the human figure.” His passion for Japan is so strong that it drove the artist to leave Paris to seek Japanese light in the Midi, the south of France: The review also follows Van Gogh on his journey to Arles (works such as the View of Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer or the Green Vineyard, which were absent from last year’s exhibition in Rome, are from this period) and then briefly gives an account of his illness and subsequent period of hospitalization in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, which brought him closer to nature, partly through reading. In a letter dated July 2, 1889, Van Gogh writes to his sister Willemien as follows: “I am quite absorbed in reading the Shakespeare that Theo sent me here, where I will finally have the calm I need to tackle a somewhat more difficult reading. First I took the series of kings, of which I have already read Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V and part of Henry VI - since these plays were less familiar to me. Have you ever read King Lear? But anyway, I guess I don’t want to push you too much to read such dramatic books since I myself, coming back from this reading, am always obliged to go and look at a blade of grass, a pine branch, an ear of corn, to calm myself down.”

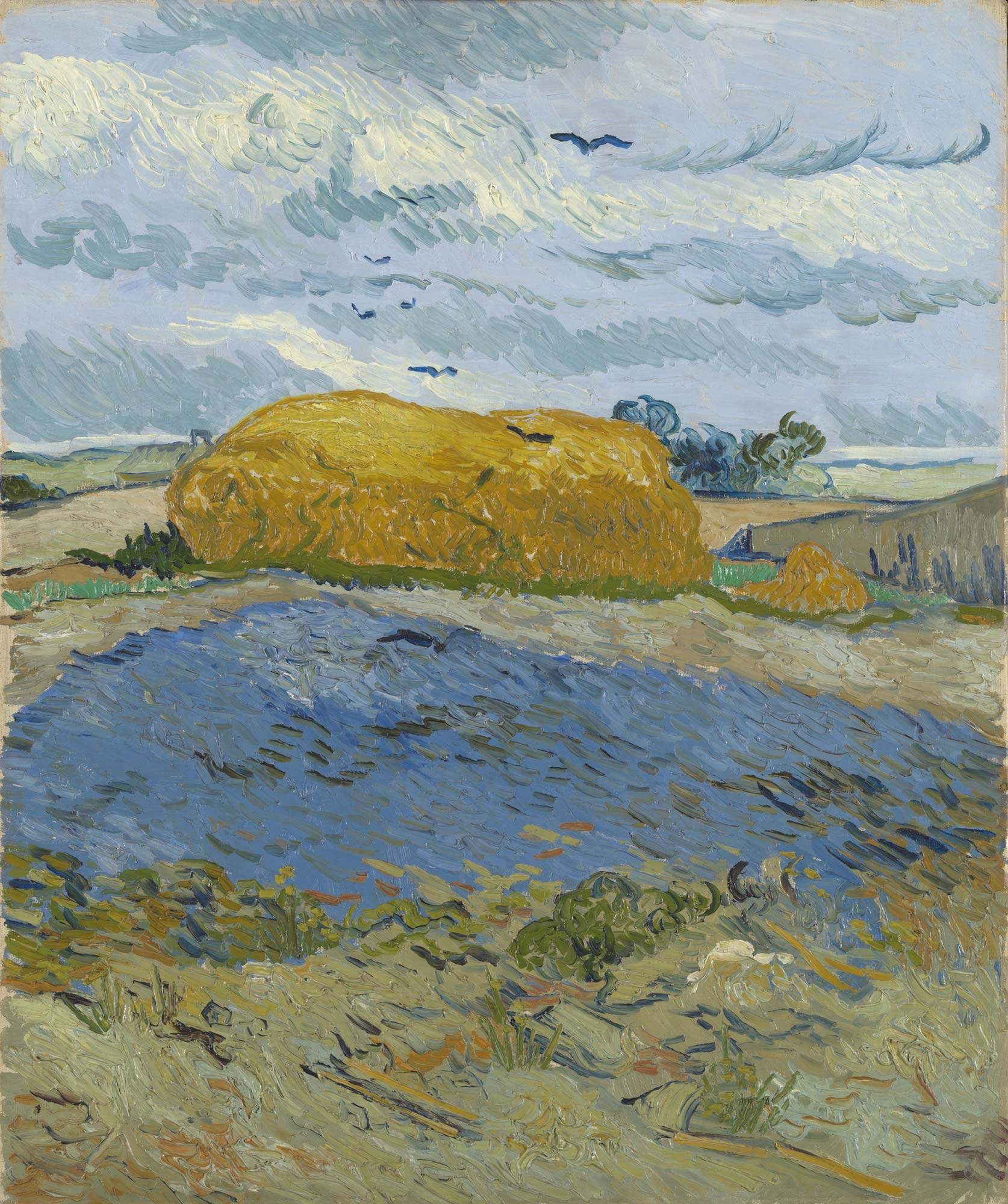

The last Van Gogh, a Van Gogh observing with an almost mystical attitude the nature around him, fell in love with Rembrandt, who suggested that he try to seek the essence of what he observed. He was convinced, as he had written to his friend Bernard in 1888, that only Rembrandt and a few others (Delacroix and Millet), in painting religious subjects, had been able to capture the metaphysical sense of Christ’s sacrifice. And looking at Rembrandt’s works, Van Gogh is spurred on to capture the metaphysical bearing of the religious subject: “If I stayed here I would not try to paint a Christ in the garden of olives, but just the olive harvest as it is still seen today, and then give in it the right proportions of the human figure, which would perhaps make people think of just that.” The closing of the exhibition is therefore for the Olive Harvest , which arrives together with the unmissable Sheaf under a cloudy sky, presaging Van Gogh’s end, and concludes the tour with an image that is the result of an intimate meditation, with a strong religious sense, but still rooted in what the artist had read or carefully observed.

An unusual, unprecedented exhibition, made from the same material that the Italian public has already seen several times in recent years. One will be able to approach it in the same spirit in which one often visits Van Gogh exhibitions: to go and be transported by the paintings of one of the world’s most beloved painters. Or one will take the opportunity to get to know him more deeply, to enter with the soul and mind inside his paintings, to understand the reasons for his choices.

Why not. Ilaria Baratta

It will be the short distance between two exhibitions dedicated to Van Gogh, the one that ended in May 2023 set up n the exhibition spaces of Palazzo Bonaparte in Rome entitled Van Gogh. Masterpieces from the Kröller-Müller Museum and the one still in progress until January 28, 2024 at Mudec in Milan, Van Gogh a cultured painter, but to be honest while visiting the latter I did not feel the same desire to continue the discovery of the exhibition path as on the contrary I felt spurred on, step by step, room by room, in the previous one. In both cases the works on display came from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, a museum whose collection of Van Gogh’s paintings and drawings ranks immediately second to that of the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, so it holds extraordinary masterpieces, such as the painter’sSelf-Portrait of 1887 featured in both exhibitions, but probably the substantial difference lies in the narrative, in that narrative continuum that accompanies the visitor along the exhibition route. And which as a visitor I perceived to be quite stringent in the Mudec exhibition. I try to explain myself better.

The various phases of the Dutch artist’s painting activity are all present in both the Roman and Milanese exhibitions: starting from the Dutch period with the Etten years, we move on to The Hague, where Van Gogh moved in late 1881, then to the village of Nuenen where Vincent moved in 1883 and where his father was a Protestant painter. He then moves on to Paris, the city where his art changes: if in the Dutch period the artist focuses his attention on the humble and their conditions in the work of the fields and mines, in France his Impressionist period begins and his works, first characterized by gray and brown tones, become more and more colorful, reaching their climax in the Arles period, when the colors on the canvas become brighter and brighter, with splendid yellows and blues, to transfer the warmth of Provence into the paintings. And it was in this Mediterranean-kissed region of France that Van Gogh found his Japan, for which the painter nurtured a strong passion: in fact, he was a great collector of Japanese prints. After the happy period in Arles, there then follows hospitalization for mental problems at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole nursing home near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where nevertheless Van Gogh did not stop painting as he realized that painting was a real cure for him. And finally the last Van Gogh, when his landscapes and in particular his wheat fields manifest with increasing evidence the signs of his existential suffering, which would soon lead him to take his own life. This profound suffering was underscored at the Palazzo Bonaparte exhibition with a painting of strong emotional impact, the Desperate Old Man, who sits on a chair and brings his hands to his face, over his eyes, in a sign of despair; the exhibition at Mudec, on the other hand, ends on a softer note, with a cloudy sky under the sheaves.

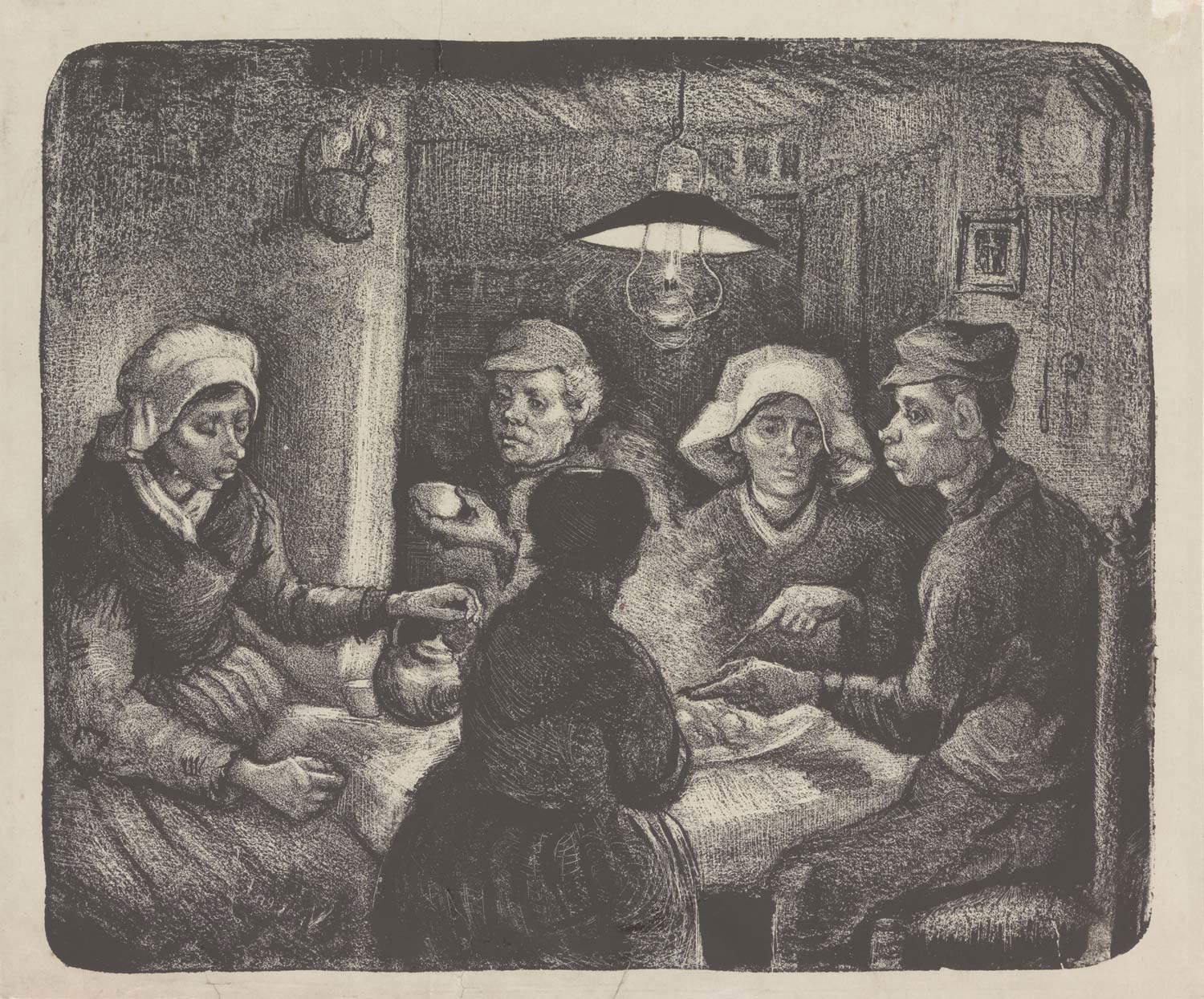

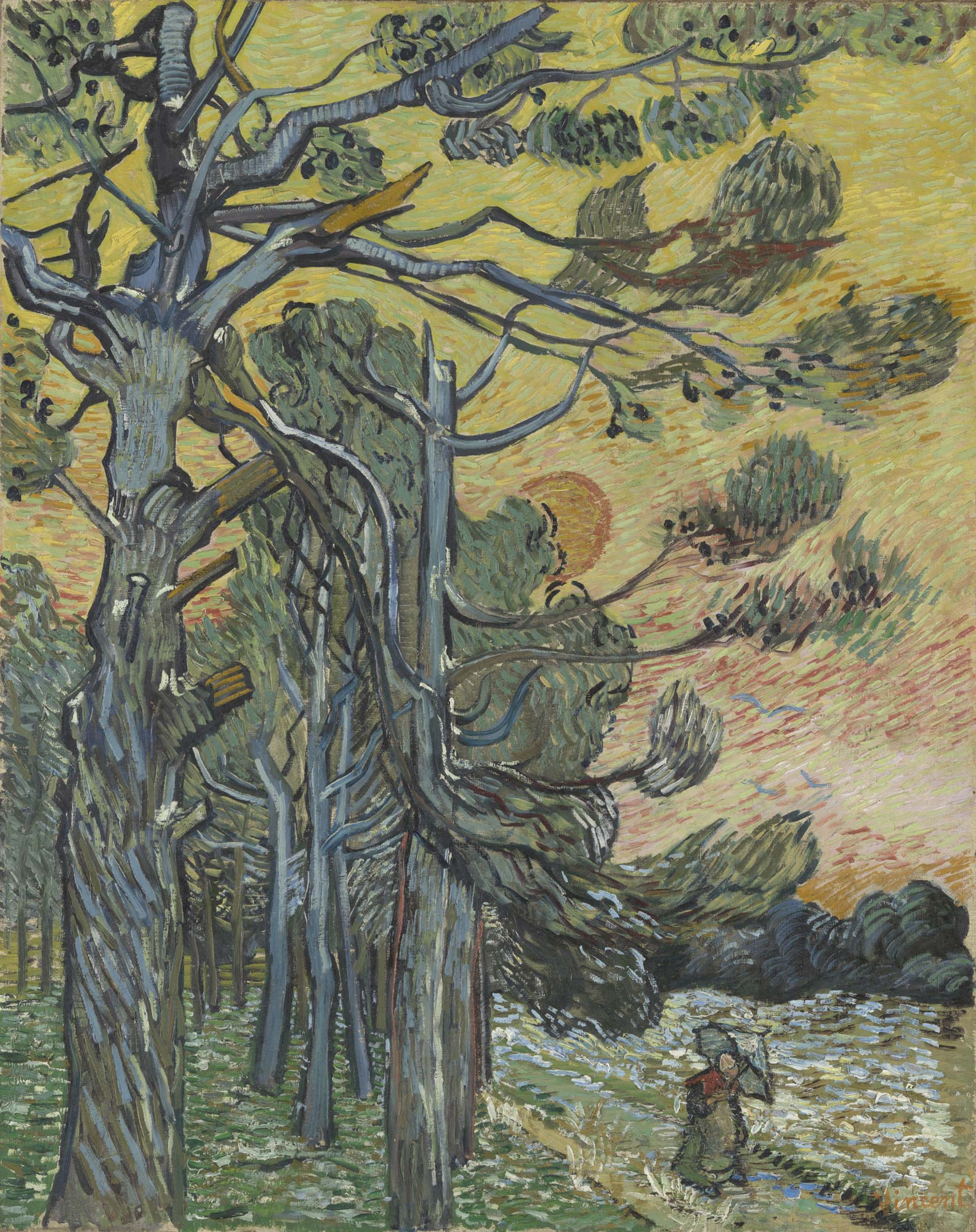

Thus, to retrace Van Gogh’s story came the works from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, about 40 for the Milan exhibition and about a dozen more for the Roman one: we find in both, as mentioned above, theSelf-Portrait, but also The Potato Eaters, The Peasant Woman Harvesting Wheat, Woman Sewing and Cat,Interior of a Restaurant, The Pines at Sunset, Sheaf under a Cloudy Sky. È true that the intent of the two exhibitions was different, to tell the human and artistic story of the Dutch painter in the one in Rome and the one in Milan to propose a novel reading of Van Gogh’s works to highlight the relationship between his pictorial vision and his cultural sources, in particular through his passionate interest in books and his fascination with Japan, to give the idea of an educated painter, going beyond the account of Van Gogh as a painter marked by suffering, his difficult character and episodes that have now entered the collective imagination, such as the cutting off of his ear following his quarrel with Gauguin. But if the former gave the impression of dealing with topics in a broader way, at Mudec we seem to be witnessing an overly concentrated succession of references, a feeling that was particularly evident in the first part, the one devoted to the period before the Impressionist Van Gogh.

It starts in the coalfield of Borinage, Belgium, where Vincent is a lay evangelical preacher in the mining community. In fact, the exhibition opens with the drawing The Bearers of the Burden, which depicts a group of women, their backs bent, carrying sacks of coal in a desolate landscape: an image that depicts the plight and suffering of the lowly workers and is considered a symbolic work of the transition from preacher to painter. Here a panel makes it known that his two “new” gospels are Jules Michelet with his History of the French Revolution, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, the author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Immediately afterwards, a comparison with Jean-François Millet, an artist who profoundly influenced Van Gogh for his religious view of nature, is presented: Vincent then practices the art of drawing by copying Millet’s works, including, as seen in the exhibition, The Hoekeepers, The Angelus, and The Sower. Also present in a display case is Lavieille’s volume of engravings with types of peasants engaged in the various labors of the countryside, which the latter produced with great fidelity to Millet’s The Field Workings , which Van Gogh also copied as an exercise. The exhibition then continues with the Etten years, where Vincent arrived in the spring of 1881 and where he made drawings of landscapes, peasants at work and people he had posing in interiors, such as Woman Sewing with Cat, offered here side by side with Thomas Hood’s Song of the Shirt . A display case is then devoted to various books intended to give insight into his immersion in “realism-realism.” one thus finds Zola, John Leech, Dickens, Luke Fildes, and next to it one sees Woman on her deathbed, through which one wants to mention the Hague period and his relationship with Sien Hoornik, a pregnant prostitute whom Vincent welcomes into his home, with whom he has an affair (he wants to marry her to remove her from her condition, but the project provokes the indignation of her family members), and who in some works serves as her model. And then Nuenen, where Van Gogh studied Charles Blanc’s Color Star , a source of new experimentation, as seen in the Peasant Woman’s Head exhibited here. Peasant women are also depicted here in drawings such as Peasant Woman Tying a Bundle of Wheat Herbs, and the Potato Eaters, also featured in the Roman exhibition, are also shown here. A parenthesis also declares Van Gogh’s passion for birds’ nests. All too concentrated, without giving space for a greater exploration of a theme, that of his book culture and cultural sources, which in itself would be very interesting.

With a new room opens the chapter of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism in which the protagonist is theSelf-Portrait already mentioned, a room where, moreover, visitors tend to crowd together, creating clutter (it would also be necessary to open a parenthesis on guided tours dedicated to children and young people, because in this very room, on the morning I visited the exhibition, the guide had made the entire group sit on the floor, occupying the entire room and thus leaving little freedom of movement for other visitors: a custom that should be more controlled, as I do not believe that small and young visitors have extreme need to sit on the floor every two by three, given also the concentration of tour groups that characterizes this exhibition).

The exhibition, however, continues with Paris, Arles and Japanism; the section on Van Gogh’s relationship with Japan is better, where the artist’s passion for the Japanese world is well understood thanks in part to comparisons with major ukiyoe artists, such as Hiroshige.

The exhibition then draws to a close with his hospitalization in the psychiatric hospital, and here in one panel it is stated that Vincent returns to his old readings, rereading Shakespeare in particular. They also find space here for the Pine Trees at Sunset that Van Gogh painted in December 1889 precisely in Saint-Rémy, when he is given the opportunity to leave the hospital to visit the countryside, during the moments when his illness gives him respite and he thus tries to obtain permission to devote himself to painting, because it cures for him. Here at last are clouds appearing on the sheaves in the last room, a sign of that existential malaise and suffering that becomes more and more pressing, until it leads the painter to his suicidal death.

Van Gogh cultured painter is therefore in my opinion an exhibition that intends to highlight a very interesting theme such as that of the artist’s connection with books, but which in my opinion could have been developed more thoroughly, dwelling more on the comparisons between the works and the artistic-literary references. Precisely because it is little known it would have deserved more space in my opinion. Still, it is worth a visit if you have not had a chance to see the exhibition at the Palazzo Bonaparte: the presence of masterpieces from the second most important museum in terms of quality and quantity of the artist’s works is definitely worth the trip.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.