All about the restoration of Rosso Fiorentino's Deposition

It was one of the most eagerly awaited restorations in recent years: the one on the Deposition from the Cross by Rosso Fiorentino (Giovanni Battista di Jacopo; Florence, 1494 - Fontainebleau, 1540), an extraordinary masterpiece of Tuscan Mannerism(here an in-depth article on the work). The intervention on the work preserved at the Pinacoteca Civica di Volterra was entirely funded by the Friends of Florence Foundation thanks to donations from John and Kathe Dyson and the Alexander Bodini Foundation and was was carried out under the guidance of the Scientific Technical Committee for the Study, Monitoring and Restoration of Rosso Fiorentino’s Deposition - Pinacoteca e Museo Civico di Volterra, coordinated by the Soprintendenza archeologia belle arti e paesaggio for the provinces of Pisa and Livorno, with the participation of the Municipality of Volterra (Pinacoteca e Museo Civico / Ufficio Cultura, Turismo ed Eventi), the Diocesi Vescovile di Volterra (Ufficio Beni Culturali Ecclesiastici), the Friends of Florence Foundation and Andrea Muzzi.

Consideration began to be given to restoring the work in 2017, following the exhibition The Sixteenth Century in Florence held that year at Palazzo Strozzi, which featured Rosso’s altarpiece as one of the featured works. On that occasion a reflection was born between art historian Andrea Muzzi then Superintendent of Pisa and Livorno restorer Daniele Rossi, the Diocese and Municipality of Volterra and Friends of Florence on the state of conservation of the masterpiece. Reflection that led shortly thereafter precisely the restorer who had already worked on Pontormo’s Deposition also supported by Friends of Florence and exhibited in the same exhibition, to present to the American foundation the project of intervention with the high supervision of the Superintendence and the agreement of the owners. The restoration began during the Covid pandemic, in September 2021, and was carried out directly in the Pinacoteca Civica in Volterra by restorers Daniele Rossi for the pictorial part and Roberto Buda for the wooden support. The “open construction site” allowed the museum not to completely take the work away from visitors and to show its complex restoration work.

The

The

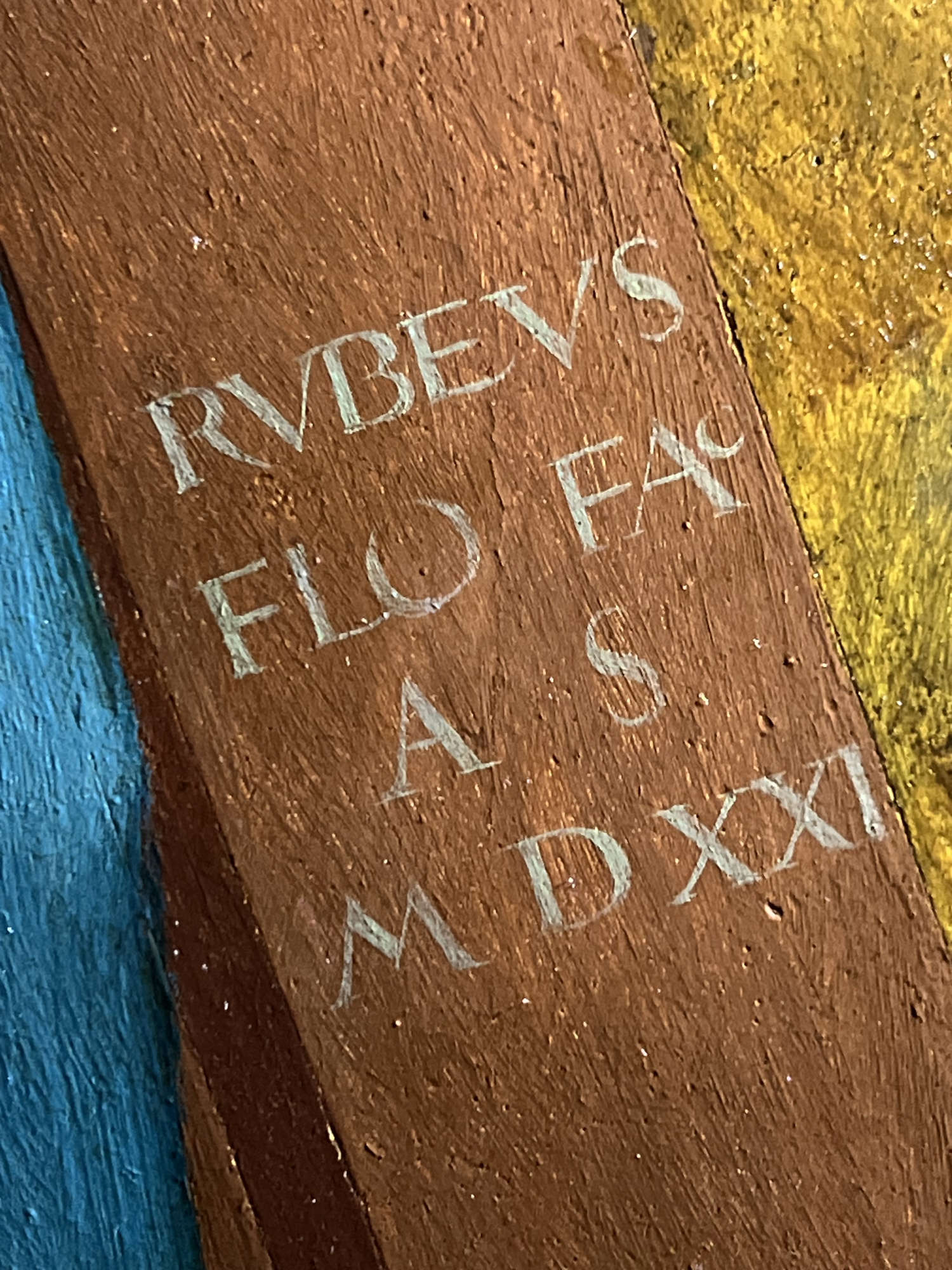

Signed and dated 1521, the Deposition was painted by Rosso Fiorentino during his stay in Volterra, which probably lasted about a year and was completed between the end of 1521 and the beginning of 1522, a period in which he also painted the Villamagna Altarpiece, now housed in the city’s Diocesan Museum. The Deposition was originally placed in the chapel of the Compagnia della Croce di Giorno, who commissioned the work, at the church of San Francesco in Volterra and remained there until the end of the 18th century. It was then placed in the chapel of San Carlo inside Volterra Cathedral and in 1905 passed to the Pinacoteca Civica, where it is still displayed today.

The delicate intervention was necessary to address two critical aspects that the panel presented following a visual examination after the 2017 exhibition: the distressed situation of the wooden structure, primarily due to the now blocked crossbeams, which was reverberating on the paint film in the form of color deadesions, and the now altered pictorial retouching attributable to previous restorations, now altered and in dissonance with the original colors.

In September 2021, five hundred years after the work was completed (finished by Rosso Fiorentino in 1521), numerous diagnostic investigations, chemical analyses and photographic documentation were carried out. The restoration was completed in October 2023. Today, with the intervention completed, we know more about Rosso Fiorentino’s modus operandi , his peculiar painting technique and the secrets behind this enormous altarpiece.

Detail of the

Detail of the

Previous restorations

Over the years the painting has undergone at least four restorations: an early restoration is documented in the second half of the nineteenth century, while in 1935, on the occasion of Italo dal Mas’s intervention, the work was transported on a bed on top of a truck to Siena, and then left, once the restoration was completed, in the direction of Paris (together with Pontormo’s Deposition in Santa Felicita in Florence) for the great exhibition commissioned by Mussolini at the Petit Palais. In 1947 a further restoration was carried out in Florence by restorers Lumini and Sokoloff exclusively to the pictorial surface. The last two restorations are recorded in 1974, by Nicola Carusi, and in 1978, by Giannitrapani, during which the wooden support underwent major intervention.

The intervention on the support

The current measurements of the planking are about 200 x 340 cm, the thickness is about 5 cm. The work has not undergone any resizing. Originally, the planking was prepared with five poplar wood planks joined at sharp angles with cold casein glue and supported by four dovetail crossbeams. The choice of planks and the cuts made with care even in thickness so that they would not board, also included a large knot in one of the planks, which over time caused a small opening.

“In the current restoration work,” explains Roberto Buda, “the (unsuitable) aluminum crossbeams and their anchoring bridges were removed. The pine wood restoration wedges (unsuitable) and some walnut butterfly inserts (unsuitable) were replaced with poplar wood wedges and dowels along the joint lines of the planks, so as to obtain, where possible, a correct alignment of the pictorial surface. Each currently inserted chestnut wood crossbeam was constrained to the substrate by gluing prepared cylindrical chestnut wood dowels, bearing a stainless steel screw and conical springs to accompany the natural movements of the planking and to ensure a degree of elasticity. Once the restoration was completed, anoxic disinfestation and subsequent treatment with woodworm biocide was carried out.”

The

The

The materials and the restoration of the surface

The preparation of the painting was made by spreading a single layer of rather unevenly mixed gesso and protein gl ue and bovine glue on top of the panel; minimal traces of egg yolk were also detected, which could be attributable either to a possible intentional addition or to residues of a not perfectly clean brush.

On the preparation, below the pictorial layers, there is evidence of linseed oil being applied to saturate the porosity of the chalky preparation.

At some of the samplings, the presence of black carbon granules, which can be interpreted as a preparatory drawing, was evident above the preparatory layer. The pictorial layers were made using a raw linseed oil-based binder mixed with the various pigments.

Based on the results obtained through chemical analysis, it was possible to trace the preparation of the pictorial layers, the binders and the original colors of Rosso Fiorentino’s palette. His palette is very rich in valuable pigments such as lacquers (Lacca di garanza or di Robbia and Verderame), Orpimento yellow, Lead and Tin Yellow called Giallorino, Cinnabar red, Azurite and Malachite.

It has also been noted that the painter added a particular salt such as Rock Alum (a material from quarries near Volterra and possibly used as a preservative) and some glass powder to the impasti to give greater luster and transparency to the pictorial layers. Investigations in grazing light emphasize the more full-bodied brushstrokes over the more liquid and transparent ones. Rosso also uses flat brushes of various sizes, but also with very thin tips to outline the shadows on the anatomical details of the various characters.

The preparatory drawing

The preparatory drawing, revealed by reflectography, is transposed freehand onto the cast board by means of a lightly charred, “dry point” type of charcoal and a thicker one. In many areas the stroke is brushed over and is shaded, while in other areas the brush marks are repeated diagonally to indicate shaded areas.

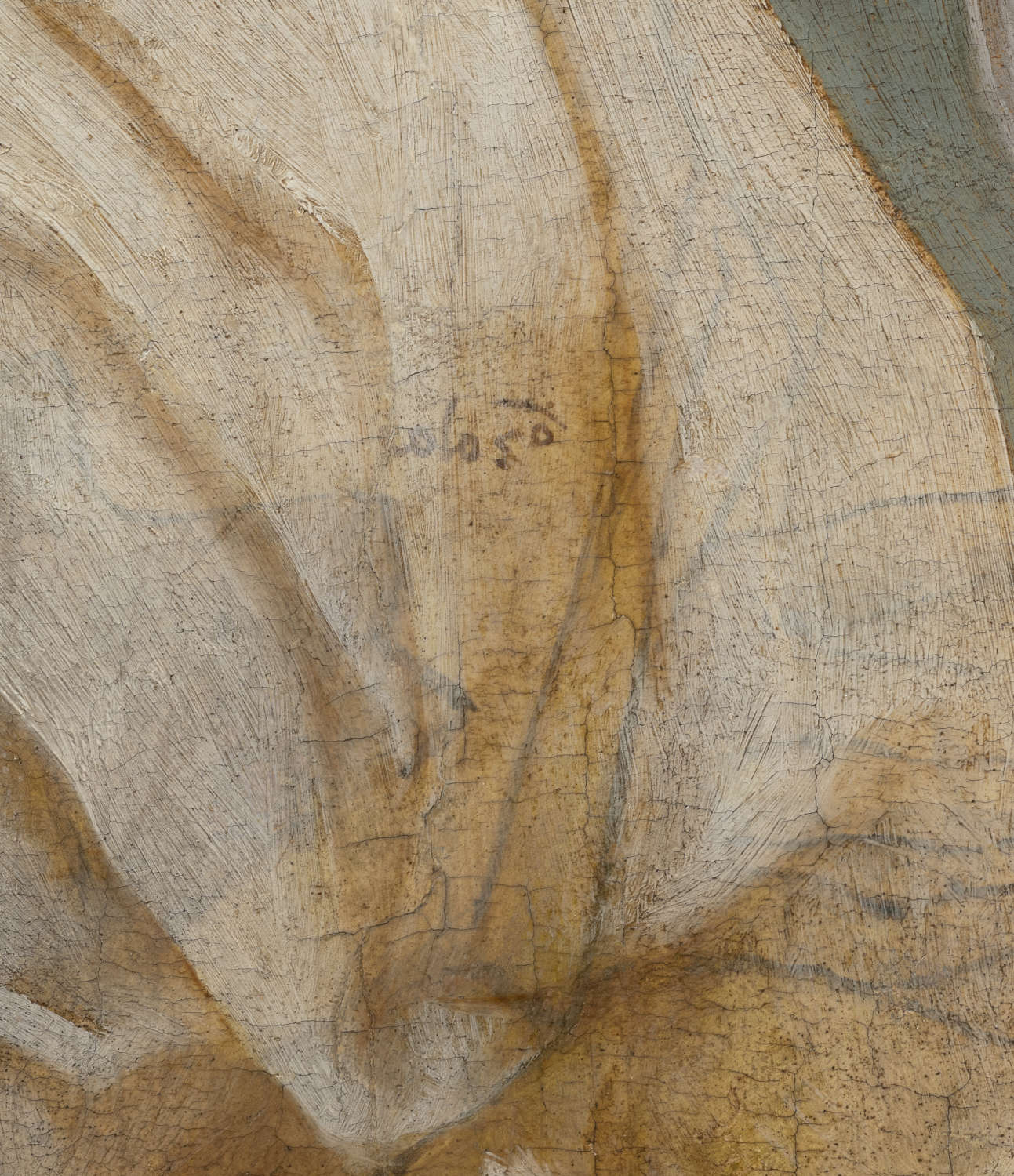

A few repentances are noted in the process such as the legs of Jesus Christ or the arm of the boy holding the ladder, but the most striking one ever revealed to date appeared on Mary’s arm and hand still present and drawn on the shoulder of the pious woman but definitively covered by the white and ochre folds of the robe. Then, at this stage of the painting’s composition, one can observe the arm of Our Lady around the neck of the left-hand Mary, whose hand was completely supporting her in aid of the other Mary’s gesture. In this way, the Mother of God appeared to be fainting, while now her severe pain shocks her but without the abandonment of her senses.

The preparatory

The preparatory

The restoration

The cleaning of the pictorial surface employed different solvents and media to allow for a gradual lightening of the restoration varnishes previously spread on the polychromes. In particular, on the red and green organic lacquers but also on the yellow-orange orpiment-based coats, the intervention was calibrated and some residues of older, but not original, varnishes were retained; while the retouches on the gaps and splits were removed punctually with the use of an optical microscope.

The cleaning brought to light some inscriptions: although these inscriptions were known to have been made by Rosso, in particular, under the color of the ribbon on Magdalene’s head (“azurra”) or on the pious woman’s robe (“coloso”), used as a reminder for the painter himself, other words emerged during the cleaning. Notably the words “biffo” on the robe of the boy holding the ladder, referring to the purple color described by Cennino Cennini in his treatise; and “biffo ciara” on Christ’s loincloth. Others were found on the drapery of the man leaning out as “azure” and “yellow.” Rosso Fiorentino remains partly faithful to his notes but on some colors he shows that he changed his mind totally, substituting at the last his initial thought. The inscriptions emerged thanks to investigations made on the basis of a ferrogallic ink used mainly in drawings on paper.

The writings of

The writings of The writings of

The writings of The writings of

The writings of The

The

On the sky, the removal of the altered varnishes has allowed the recovery of the sky-blue color, based on azurite and white lead, which is still fully appreciable, highlighting, however, the presence of diffuse stains similar to the effect of splashes, probably attributable to old fixatives altered and incorporated into the pictorial layer in such a way as to make it preferable to keep them in order not to risk affecting the original color. (As documented by some photos in the archives of the Soprintendenza (Carusi 1974).

The removal of the restorative fillings present on the gaps and inside the woodworm holes was done mainly by mechanical means and partly with solvent gel on the cracks, consistent with the preservation of the original. The restorers chose to retain the gray-colored fillers affixed in previous restorations to avoid weakening the color surrounding the gap.

“The subsequent fixings based on acrylic resin,” illustrates Daniele Rossi, "were carried out near the splits, inside which there were fillings with glue and wood sawdust that were totally removed during the plank alignment operation where possible. Much of the surface and woodworm holes were freed and cleaned with rectified gasoline, then grouted again with synthetic putty. The final stuccoes, executed with plaster and glue, were surface-treated to mimic the ductus of the relief brushstrokes, and burnishing with agate stone was performed limited to the larger gaps. Pictorial reintegration was carried out with watercolors based on stable pigments and gum arabic by the “hatching” method on the interpretable gaps previously filled in coarse strokes but following the same technique, and on some abrasions with lowering of tone. Many micro-lacunas and woodworm holes were retouched with stable gum arabic-based opaque tempera. Final brush painting was conducted with oval brushes of semi-synthetic hair and highly stable synthetic varnish. Final reintegration after painting was conducted with stable natural and synthetic powder pigments after further manual grinding using the same paint and White Spirit. Final painting was conducted with the same varnish by spraying.

The occasion was also a very valuable opportunity for in-depth study of the work: in fact, today, after the restoration is complete, there is greater knowledge about Rosso Fiorentino’s way of working, the painting’s meanings and how the artist chose to depict the Deposition of Christ from the Cross, arriving at a unique synthesis of spirituality, pain and compassion. Once the restoration was completed, the painting was relocated to Room 11 of the Pinacoteca Civica di Volterra specially set up also thanks to a partnership between the Municipality of Volterra and Iren luce, gas and services.

|

| All about the restoration of Rosso Fiorentino's Deposition |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.