Divisionism in Italy. Origins and development of painting technique.

Divisionism was an Italian painting phenomenon at the turn of the penultimate decade of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth century, fitting more widely into the international current of Neo-Impressionism, which followed and renewed the technical experimentation and research of Impressionism.As in France, also in Italy at the end of the 19th century, knowledge of theories and scientific studies on color led to pictorial procedures aimed at increasing the visual sensation of the image and overcoming historical-naturalistic painting.

Taking as their starting point the Impressionist practice of using broken color and the juxtaposition of complementaries, the Neo-Impressionists were mainly interested in depicting the effects of light and achieving maximum luminosity by juxtaposing pure colors on the canvas and unmixed on the palette, to achieve fusion in the eye of the observer. Because colors were used divided, this current of Italian painters is referred to as “pointillism.”

Similarly to what happened in France with "pointillisme" (pointillism or pointillism), theorized and adopted by Georges Seurat (Paris, 1859 - Gravelines, 1891) and taken up and spread by Paul Signac (Paris, 1863 - 1935) and followers, whereby tiny dots of selected and side-by-side colors went to merge at a distance into a dominant color, the pointillists applied a compositional method of juxtaposing small strokes or filaments of color. However, unlike the French experience, which was particularly attentive to the scientific aspects of technique, Italian Divisionism was loaded with symbolic meanings that aimed to produce correspondences between emotional states and forms that spoke of modernity in the age of industrialization.

With the growth of urban centers and technological progress, artists sought to capture people’s changing relationship with the city and the countryside, and turned to naturalistic subjects and social themes, interpreted with specific feeling by each of the painters. Pointillism spread to several parts of Italy but with its main artistic center in Milan, where it officially manifested itself in 1891, when the first pointillist works were exhibited at the First Triennale of that year held in Brera. Divisionist theories were affirmed by Gaetano Previati (Ferrara, 1852 - Lavagna, Genoa, 1920) in a number of writings from the beginning of the new century, but the current had been emerging for a few decades with works by Previati himself, Giovanni Segantini (Arco, January 15, 1858 - Schafberg, Switzerland Sept. 28, 1899), by Angelo Morbelli (Alessandria, 1853 - Milan, 1919) , Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo (Volpedo, 1868 -1907) and Vittore Grubicy de Dragon (Milan, 1851 - 1920), who was its initial animator, and to whom Plinio Nomellini (Livorno, 1866 - Florence, 1943) approached.

Origins and Italian development of Divisionism

The year 1886 was a turning point in the European art world, as the eighth and final Impressionist exhibition also marked the advent of Neo-Impressionism with the exhibition of Seurat’s newly completed painting, A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of Grande-Jatte (1884-86), in which the French painter applied color in dense fields of individual dots to imitate the vibrant appearance of natural light. It was one of the earliest examples of the artistic reaction to the Impressionist movement.

Seurat developed an avant-garde scientific painting style that attracted much attention and also that of art critic Félix Fénéon, who coined the term “neo-impressionism.” Neo-Impressionist painters relied on the viewer’s eye to blend the colors that appeared on the canvas. Nineteenth-century scientific acquisitions suggested that brightness is not an objective but a subjective product, as each human eye reunites light wavelengths received from outside through its own perceptual abilities. The discoveries had shown that light is not white, but composed in the eye by the seven colors of the iris. By 1890 Neo-Impressionism had become an international movement, adopted by many European artists linked to color theory and the use of small dots or brush strokes. Divisionism arose within these influences, centered in northern Italy. It spread mainly in Milan as a historical continuation of the Scapigliatura movement that had arisen in the city from the 1860s through the late 1870s.

Artist and art critic Vittore Grubicy de Dragon introduced pointillism to Italian artists in the very late 1880s and then spread their works abroad, including through the activities of the Grubicy Gallery he ran with his brother Alberto. He had spent 1882-1885 in the Netherlands, where he met and was influenced by the artist Anton Mauve, a cousin of Vincent Van Gogh and an advocate of Neo-Impressionist research. It was at the First Brera Triennale in 1891 that two works considered pointillist received the most attention. Giovanni Segantini exhibited The Two Mothers (1889-1890) and Gaetano Previati Maternity (1890-1891), now considered the debut work of Italian Neo-Impressionism and a turning point for modern art in Italy, given also the use of Symbolist themes and the influence it had on Art Nouveau and Italian Expressionism. Previati had knowledge of the perception of color in the viewer’s eye and advocated its emotional and spiritual resonance. He expounded his pictorial theories in several writings: from Memoirs on the Technique of Paintings in 1896, to The Technique of Painting in 1905 and Scientific Principles of Pointillism in 1906, to 1913’s Della pittura. Technique and Art.

Along with him, Segantini, Pelizza, Morbelli and others, appreciated as the leading Divisionist exponents, were all under contract with the Grubicy Brothers Gallery. As mentioned above, Vittore was one of the first theorists and supporters of the technique, promoting works through national and Parisian shows and exhibitions, such as the “Salon des Peintres Divisionnistes Italiens” in 1907, attracting painters from other regions of Italy, from Piedmont, Liguria and Tuscany. Having abandoned commercial activity, he devoted himself to Divisionist painting.

The group’s researches were also joined by Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla, whose work Workman’s Day of 1904 is exemplary, in experimenting with ways of breaking down light and form before coming to Futurism. One can thus place the period of the Divisionist painters in pre-Futurism. In disagreement with Pictorial Realism and the experience of the Macchiaioli, who worked from the mid-nineteenth century through spot composition and effects of the real, they argued instead for the necessity of s-composition in filaments of color to give the works suspended atmosphere and impression of dynamism.

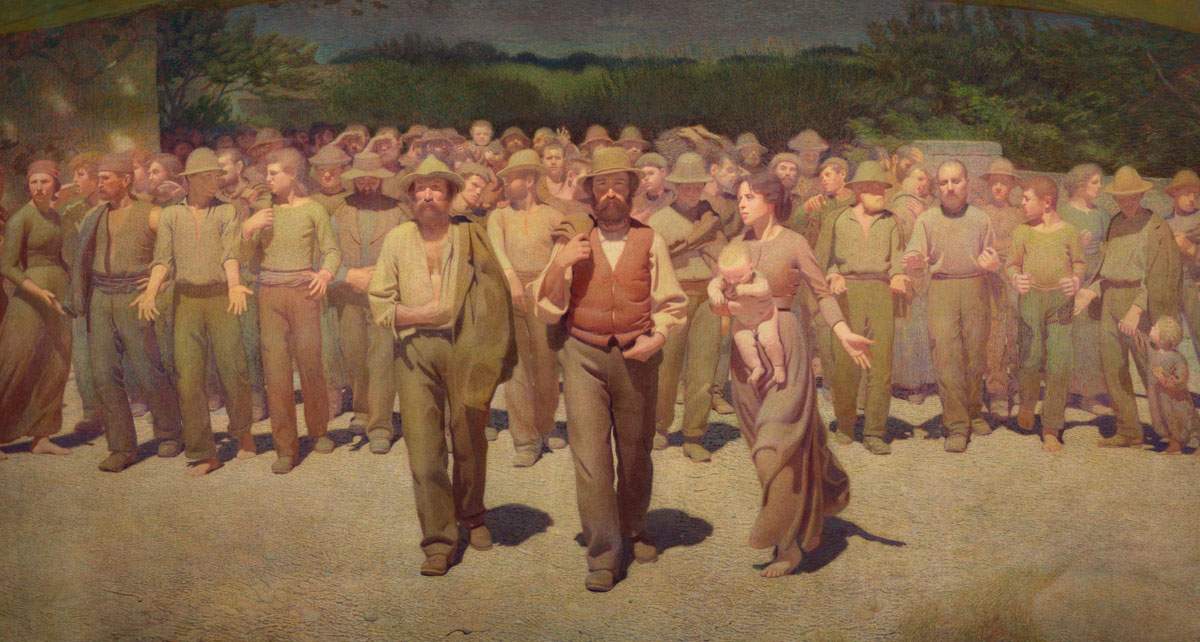

Segantini argued that art “has nothing to do with the imitation of the real, because creation is possible only through the drive of the spirit and the human soul.” So did Previati who wrote that the artist’s “task is not to copy literally everything he sees, but is an intellectual function on the forms and colors of the real....” Pointillism centered in the depiction of landscape and visions inspired by everyday life and at the same time symbolist, as interpretations of social conditions, concerning the ideas in some cases political ideas of its exponents. The most famous and representative work of the Divisionist phenomenon is by Pelizza, who was coming from a youthful experience in the Milanese Scapigliatura, entitled Il Quarto Stato of 1901. A march of striking proletariat workers headed toward their social emancipation.

The personalization of the divisionist technique of the major exponents

The technique of chromatic decomposition adopted by the Divisionists aimed to create luminous paintings of modern life, in its dreamy and at the same time searing aspects, related to the relationship with nature and animals as opposed to the city frenzy, work in the fields, and the conditions of the workers themselves, while renouncing the rawness of Realism. The pictorial procedure, which involved the representation of light as the foundation of vision, was innovative and saw each artist assert a different brushstroke and his own symbolic approach. A procedure that, according to Previati, author of late theoretical texts, “reproduces the additions of light by methodically minute separation of complementary hues.”

One feature, favored by the commercialization of industrial colors and hitherto unknown pigments, was the introduction of chrome yellow, viridian green, cobalt blue or violet. In common among the painters was a sentimental component that translated into a filamentous brushstroke precisely in Previati, more material in Segantini, attentive to chiaroscuro in Morbelli. In these major representatives of the movement, Divisionist technique was employed both as a tool for interpreting reality and for elaborating allegorical themes, in relation to developments in European Symbolism.

Grubicy, unlike the other Divisionists, adopted more defined and full-bodied brushstrokes, applying less rigorously the scientific dictates behind the decomposition of colors.His paintings feature soft, twilight lighting, as in Winter in the Mountains (1895), this was the title the artist originally gave to his work now known as Winter Poem, part of a cycle of all eight canvases, painted between 1894 and 1911(read an in-depth discussion of the cycle here). Grubicy used to paint with an impasto style of painting, dividing the image into planes and areas of light and shadow; only later, in some cases even years later, did he return to the first draft with a dense network of small brushstrokes of pure color. The outcomes of this process of true identification with the landscape were then brought together by the artist in triptychs or polyptychs, regarded as movements of a symphonic piece or cantos of a broad poem.

Previati, considered the most lyrical and visionary, used the Divisionist technique to give suspended effect to depictions of historical themes(The Sun King, 1890-1893) as well as vibrant rural scenes(On the Meadow, 1889-1890). The Dance of the Hours (1899, read more about the work here ) is one of his masterpieces, as much for its high symbolic meaning as for the quality of its pure light painting: the twelve Hours of Roman mythology, personifications of the different moments of the day, dance holding hands in flight over the earth while the sun floods the entire composition with golden light.

In Segantini , light predominantly permeates pristine nature scenes with an identifying style, full-bodied color and wide framing, as seen in Alla stanga of 1886 or La mucca all’abbebbeatoio of 1887 for example, transforming Divisionist theories into visions, and completely immersing himself in natural life: “I begin to storm my canvas with thin, dry or oily brushstrokes, always leaving there between each brushstroke a space, interstice, which I fill with complementary colors, possibly when the fundamental color is still fresh [...] The mixing of colors in the palette is a road that leads toward blackness: the purer the colors we throw on the canvas, the better we lead our painting toward light, air, truth.”

Also in his works, as of his Divisionist colleagues, especially in the last phase of his production, a mystical-symbolic component is accentuated(Life, 1896-1899) until The Death, of the Triptych of the Alps, interrupted by its sudden end in 1899. Segantini, like the others, demonstrated that through the representation of nature and the ’adherence to life, universal values could be illustrated. Pellizza in turn, although he also tackled natural subjects, was among the Divisionists the most convinced proponent of social themes along with Angelo Morbelli (known for works such as Per 80 centesimi, 1895-1897 and Un Natale al Pio Albergo Trivulzio, 1909: read an in-depth discussion of the works of Pio Albergo Trivulzio here).

He presented at the II Triennale di Brera in 1894 his first pointillist works of peasant inspiration Speranze deluse and Sul fienile (1893), later affirming his chromatic research in Quarto stato (1898-1901), his best-known painting to which he arrived after a decade of theoretical and conceptual elaboration. In this large canvas more than 5 meters long, he intended to depict not only a scene of social protest, but also a veritable allegory of the people advancing toward a radiant future, where the figures move toward the light, leaving behind a sunset. It would later be with The Rising Sun (1903-1904) that his universal vision of light would explode. Understanding the full range of iris colors in the form of dashes, he well described the effect on an observer’s view of a sunrise.

Nomellini also came to pointillism by addressing the theme of light, as in Sun and Frost (1896), helping to confirm that the pointillist technique was a means of both stylistic and emotional expressiveness.

|

| Divisionism in Italy. Origins and development of painting technique. |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.