A great many artists in the history of art have tried their hand at the theme of the Baptism of Christ, but perhaps no painting with this subject is as singular as the one by Verrocchio (Andrea di Michele di Francesco di Cione; Florence, 1435 - Venice, 1488) and Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) that is now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. It is one of the most studied paintings of the Renaissance, a problematic painting, a painting that fascinates because it provides a way to observe the relationship between the master and his very young pupil, the almost 40-year-old Verrocchio and a Leonardo in his early twenties. It is, meanwhile, one of the very rare paintings that can be assigned with certainty to the activity of Verrocchio’s workshop, an artist whose activity as a sculptor is best known, while many questions still hang over his activity as a painter. The first to report on the collaboration between Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci was Francesco Albertini, who in his 1510 Memoriale di molte statue e pitture nella città di Firenze mentioned “in Sancto Salvi tavole bellissime et uno Angelo di Leonardo Vinci,” but the most famous ancient description is probably that of Giorgio Vasari, who mentioned the painting in his Lives, both in the one devoted to Verrocchio and the one on Leonardo: “He still painted at the Frati di Valle Ombrosa a panel at San Salvi fuor della Porta alla Croce, in which is when St. John baptizes Christ,” the historiographer writes in the chapter on Verrocchio, “and Lionardo da Vinci his disciple, who was then a young man, colored there an Angelo by his own hand, which was much better than the other things.”

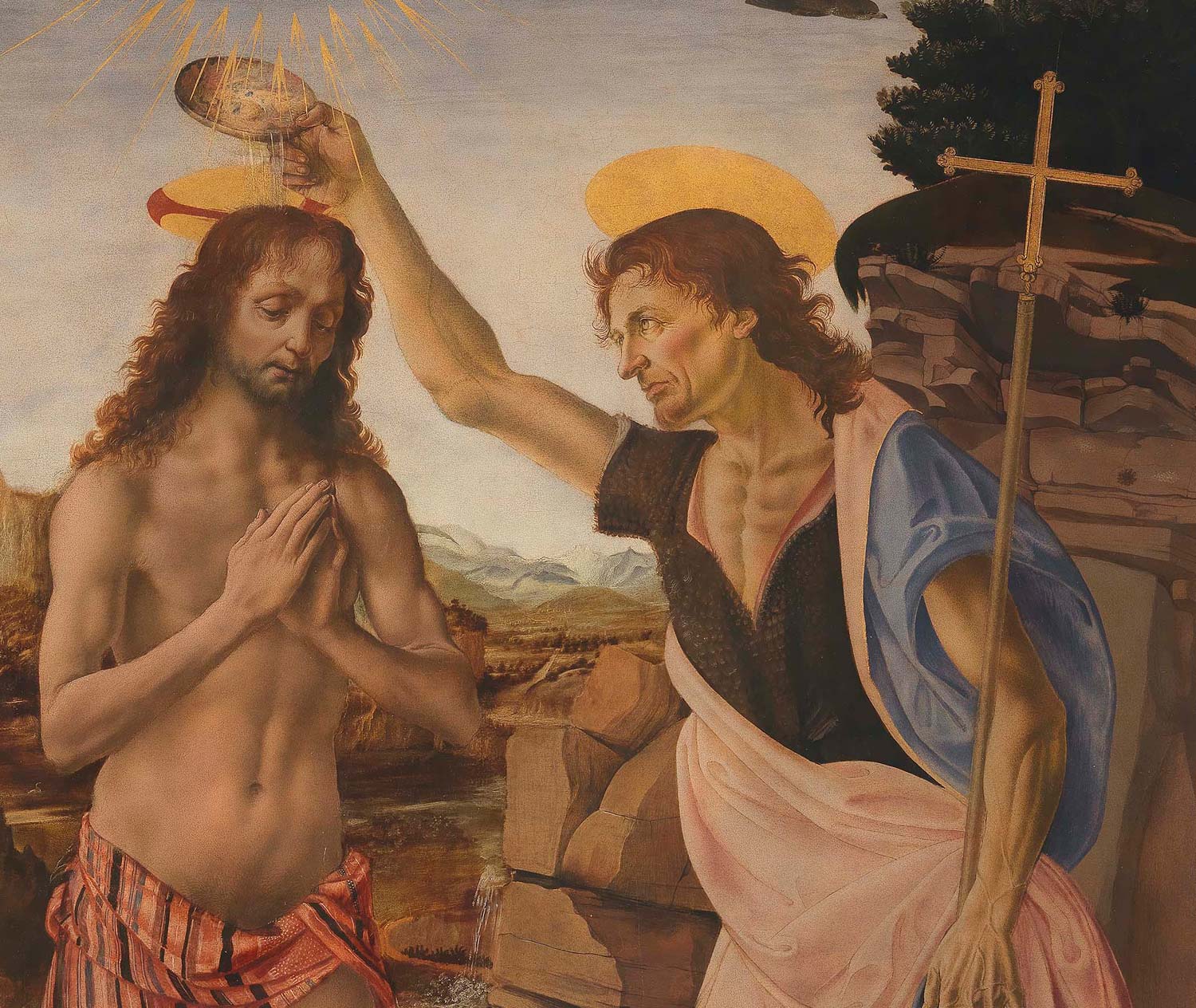

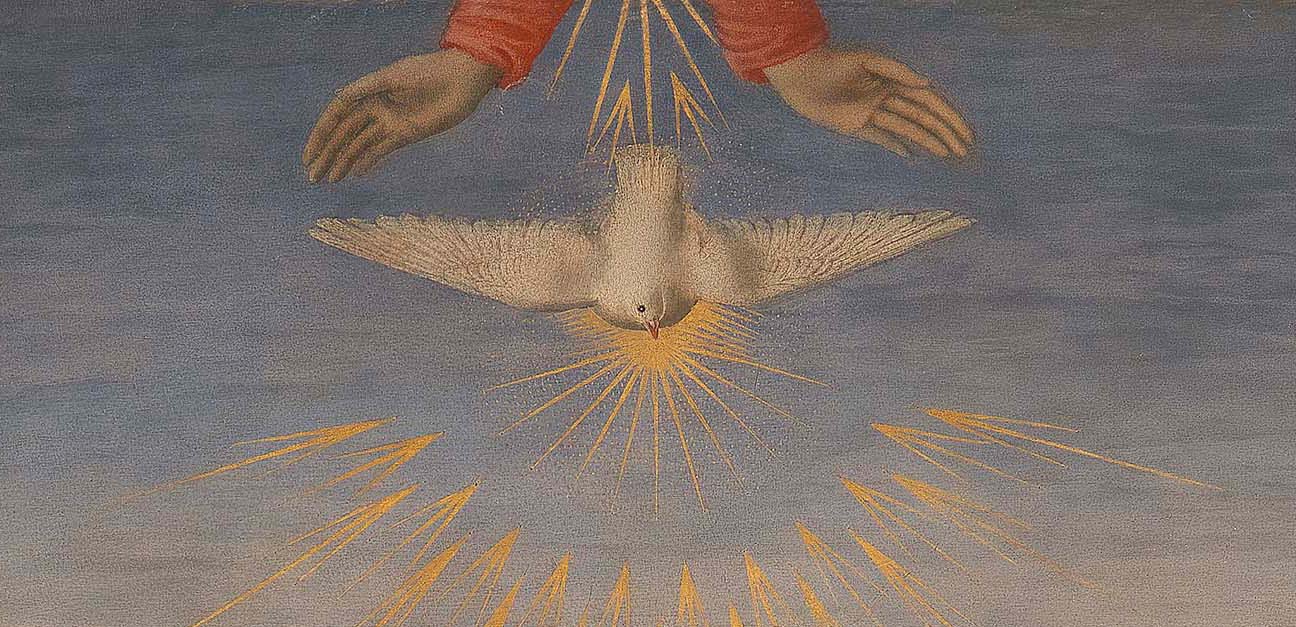

The iconography is typical of the Baptism of Christ. On the banks of the Jordan River, Jesus is receiving the sacrament of baptism from John the Baptist, according to the Gospels’ account. With his legs in slight contraposition, Christ is in the exact center of the scene, set within a triangular compositional scheme, has his hands clasped and bows his head to receive the ’water from the Baptist, who is pouring the contents of the bowl over his hair: the son of Elizabeth and Zechariah is caught leaning forward with his shoulders, balancing on his right leg firmly resting on a stone and his left leg diagonally resting on the sole of his foot, with his left arm holding the cross from which hangs the scroll with the inscription announcing the birth of Jesus (“Ecce agnus Dei qui tollit peccata mundi,” from the Gospel of John), and the right raised above the head of Jesus, over which already hovers, unfailingly, the dove of the Holy Spirit. Higher up, however, are the hands of God: the Trinity occupies the entire vertical axis of the composition and divides the scene into two equal parts. Both Jesus and the Baptist are two mature men, with hollowed faces and sculptural proportions, portrayed with realistic connotations and vigor of drawing even if, as will be seen below, Leonardo’s intervention has softened Christ’s features. More delicate are the two angels we notice on the left, and who witness the scene, one more attentive, the one who turns his gaze to the two protagonists and holds Jesus’ tunic in his hands, and the other who instead seems more distracted and averts his eyes from the event, but in fact plays a very relevant role: the group of angels in fact has the purpose of capturing the attention of the relative and channeling it toward Christ and John the Baptist. It all takes place in a rocky landscape, under a clear sky, illuminated by crystalline light, and with few plant presences: the grove on the cliff, toward which a hawk (interpreted as a symbol of evil, as opposed to the dove: we see him moving away from the scene), and a schematic palm tree, a symbol of Christ’s victory over death, on the left, an insert by a third hand to Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci, perhaps the same one that was responsible for the lesser elements in the painting (the hands of the Eternal Father, the dove of the Holy Spirit, the rocks behind the Baptist).

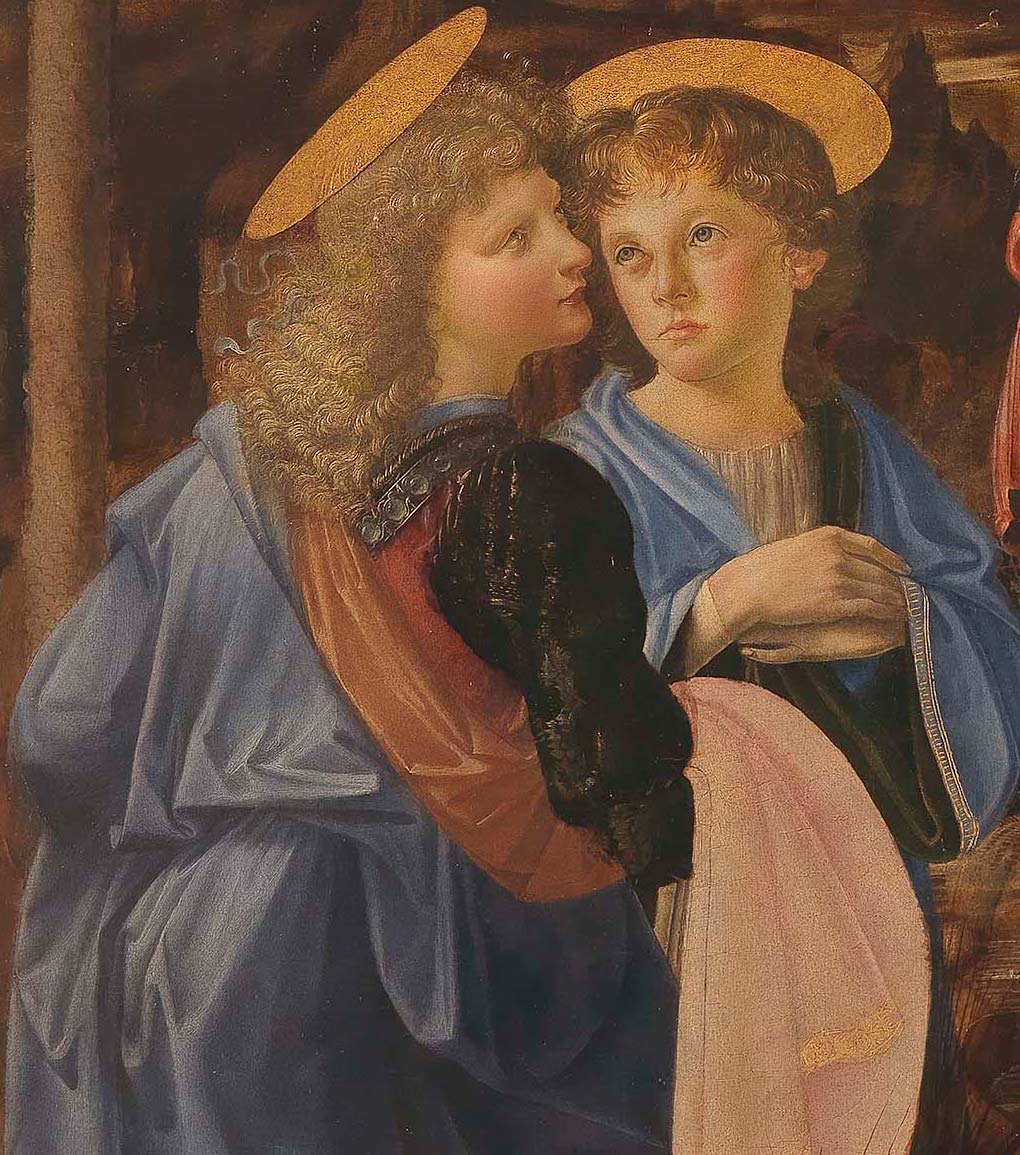

In the chapter of the Lives devoted to the Vinciano, Vasari returns to the subject of the Baptism of Christ, offering the reader some more information than the scanty note in Verrocchio’s life: it seems that Leonardo, in spite of his very young age, had executed the angel, the one on the left, “in such a manner that much better than Andrea’s figures stood Lionardo’s Angel: which was the cause that Andrea never wanted to touch colors again, disdainful that a boy knew more about them than he did.” As in the most classic of clichés, in essence, the pupil would have surpassed the master, but in this case he would have done so in a way that would have annoyed the master to the point of making him decide not to put his hand to the brushes again. Of course, we have no evidence to substantiate Vasari’s anecdote, which should, if anything, be regarded as a narrative device rather than as an episode that actually occurred (indeed, it is extremely unlikely that one of the greatest masters of the time would intend to abandon a strand of his production because he felt defeated by what we might consider an apprentice), but it is nonetheless certain that, in this painting, we can observe the contact between two different attitudes to composition.

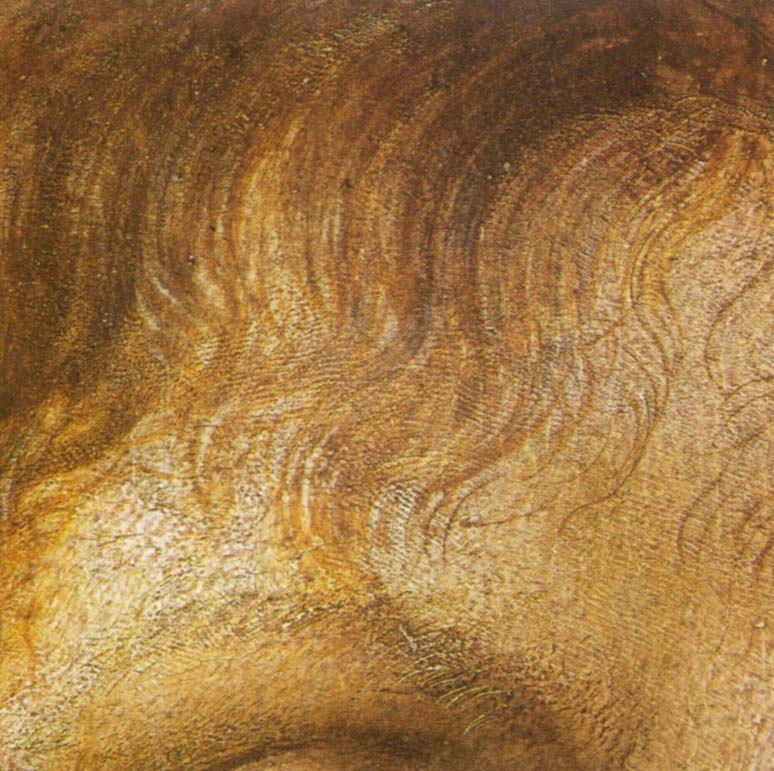

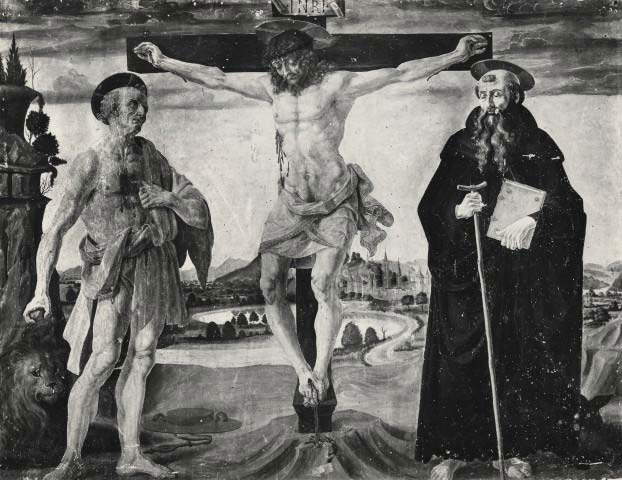

In the meantime, it is certain that this is a work executed at different times: diagnostic investigations, first carried out in 1954 and then conducted in greater depth during the 1998 restoration, have indeed revealed the superimposition of layers painted in oil on layers previously executed in tempera. In particular, it was discovered that the sky, Jesus’ hands and his loincloth, the dove and the hawk, the rock on the right with its forest, the entire figure of the Baptist, the right angel, Jesus’ robe held by the left angel, the palm tree and pebbles we see on the left, while instead the landscape in the background, the water near the feet of the characters, the left angel and the body of Jesus are conducted in oil on tempera. In addition, through reflectography, a landscape was discovered that was initially set differently than how we see it today and that, according to art historian Andrea De Marchi, resembled that which appears in Christ Crucified between St. Jerome and St.Anthony Abbot (a painting that was in the church of Santa Maria ad Argiano, in the municipality of San Casciano in Val di Pesa near Florence, and which was stolen in 1970), but for which it is also possible, again according to the same scholar, to establish a comparison with theAssumption that Domenico del Ghirlandaio frescoed in the sacristy of San Niccolò Oltrarno. Leonardo da Vinci, in the painting now in the Uffizi, did not only deal with the blond angel mentioned by Albertini and Vasari: the marked differences found in the various elements of the composition have in fact led scholars to assign him other parts of the painting, and one of these is precisely the landscape. Leonardo, writes De Marchi, “painted the riverbed, overlaying oil glazes now brownish, because the copper resinate has turned; the water-green transparencies, with plays of waves and foaming waterfalls, covered in an overabundant and non-canonical way even the feet of the Baptist.” In 2019, the director of the Museo Leonardiano in Vinci, Roberta Barsanti, moreover speculated that Leonardo’s earliest dated work, the 1473 Landscape preserved at the Uffizi Drawings and Prints Cabinet, could be traced back to his possible intervention in the landscape of the Baptism of Christ. The view in the background is very realistic (note the outlines of the mountains and the course of the river), with thin veils covering it even with a light mist.

The

The

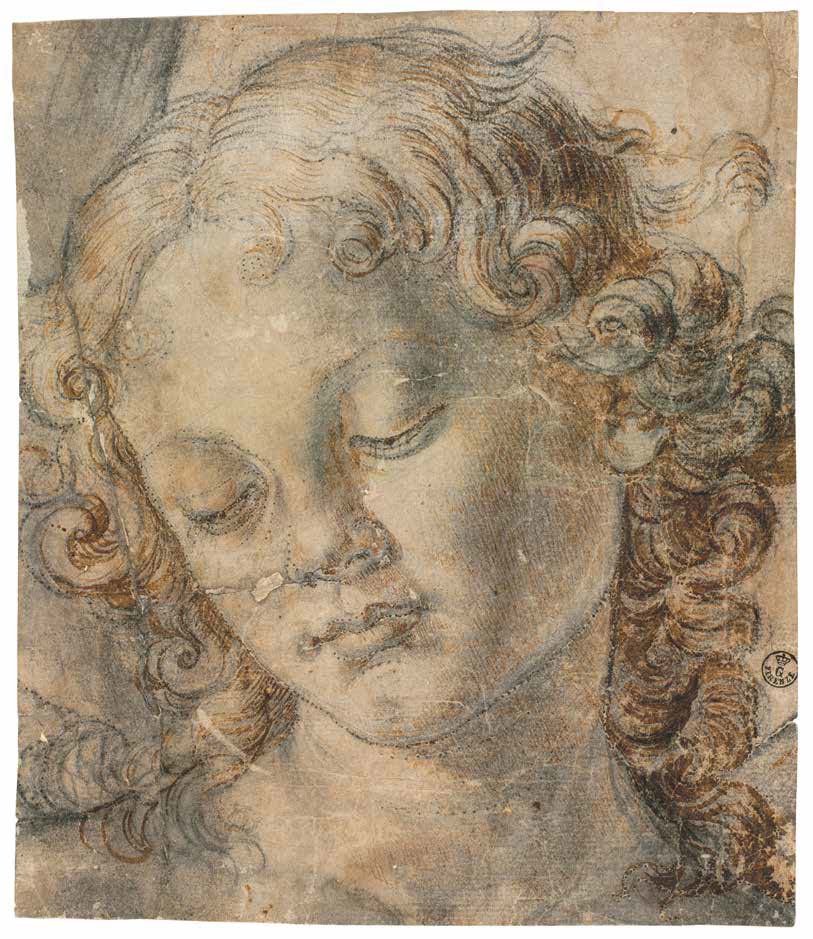

Again, it is also possible to detect Leonardo’s hand in the water reflections around Jesus’ feet: the left foot, in particular, was left in a state of deliberate unfinishedness to better suggest to the viewer the transparencies of the water in which it is immersed. Then, Leonardo also massively intervened on Christ’s body, significantly softening his figure: De Marchi suggests identifying his hand also in the face of Jesus, which is presented with “fat and sensitive drafts, animated with intense reverberations in the part in light.” Finally, Leonardo also dealt with the left part of the work, the one where we now see the palm and in which we admire his blond angel. Indeed, we have a certainty about the Baptism of Christ, as art historian Gigetta Dalli Regoli has written: “the presence of a primitive drafting based on symmetry, and therefore on a correspondence between two masses of stratified rocks located on the sides: one still existing on the right, while the other was erased by an intervention of Leonardo who covered the already traced drafting modifying the left side of the painting; the aggressiveness of the vincian intervention is attested by the famous Angel quoted by Vasari, who is proposed in an unusual version from behind, and who takes away space from his submissive companion.” The right-hand angel might find correspondence in a drawing in the Uffizi Drawings and Prints Cabinet, the Head of a Youth, given to Verrocchio, catalogued under inventory number 130 E. Some scholars, in fact (first Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti in 1954), have not ruled out a role for Sandro Botticelli (Florence, 1445 - 1510) in the Baptism of Christ, until now however still little debated: after all, it is well known that the two knew each other, that Leonardo da Vinci held his older colleague in some esteem, and above all that the two frequented Verrocchio’s workshop.

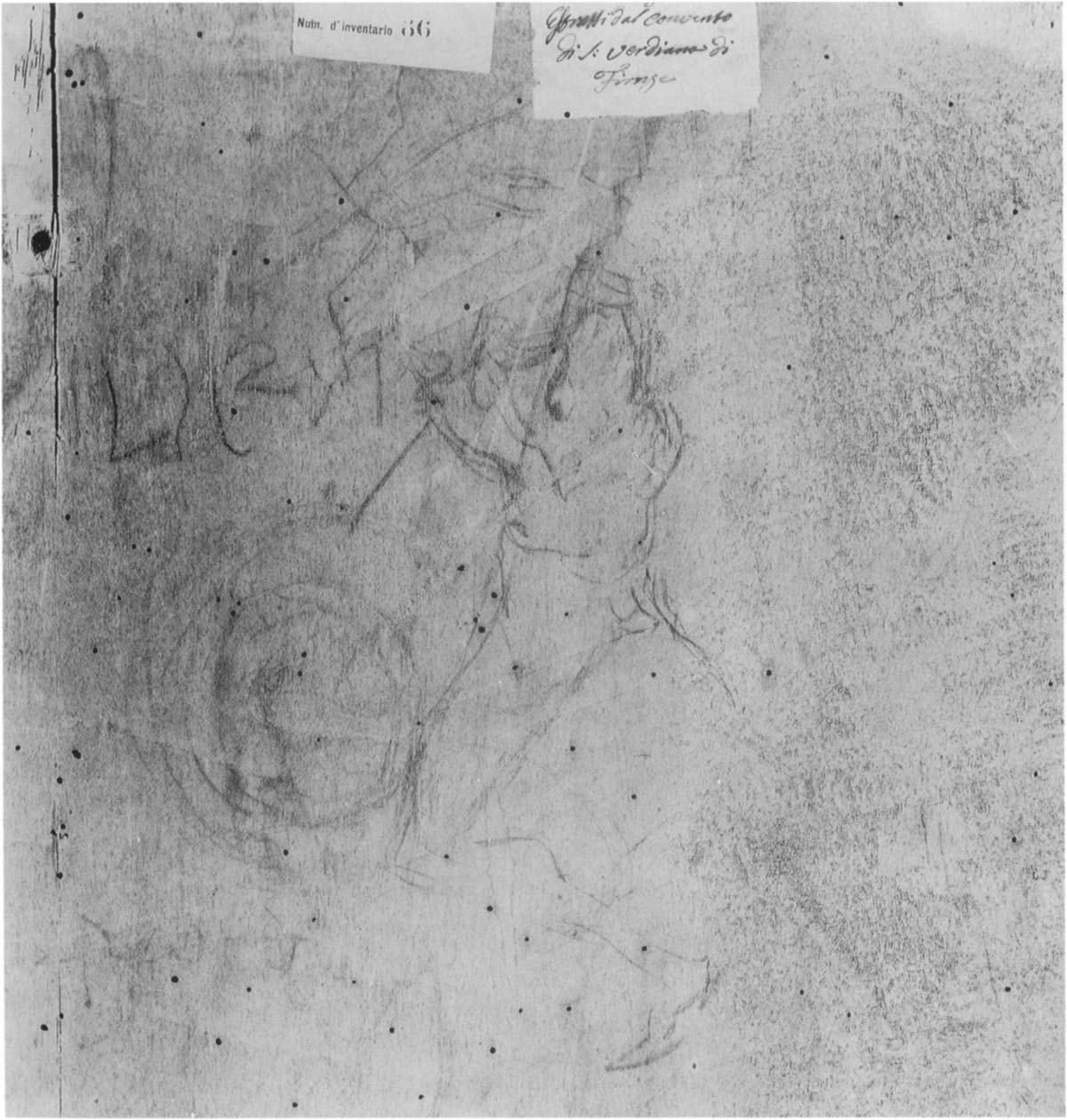

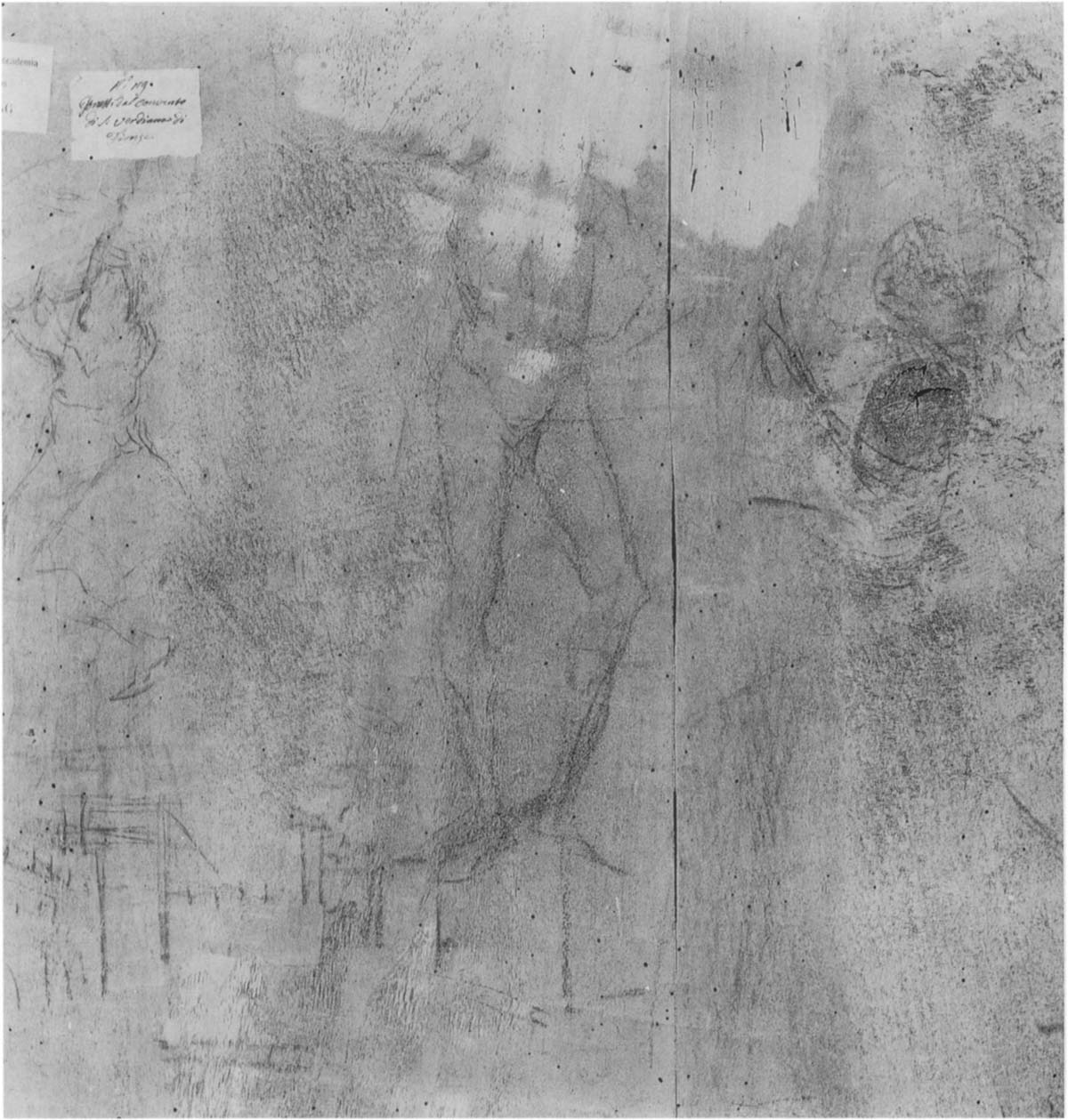

The hypothesis of a Sandro Botticelli who probably put his hand to the painting was recently taken up by Uffizi director Eike Schmidt, who in a guide to the Uffizi published in 2022 said he “totally agree” with Ragghianti’s hypothesis (“In recent years,” Schmidt wrote, “I have stopped hundreds of times to admire the face of this angel and I am increasingly convinced. Proof of this are the eyes, nose and mouth, which are identical to those in other Botticelli paintings. Those who visit this room take notice: look at the little angel on the right and then return to the Botticelli rooms. You will not be left in any doubt.”). Moreover, Ragghianti is credited with a precise stylistic analysis of the painting: the great art historian from Lucca believed that Verrocchio should be ascribed the basic tempera setting, that someone of his collaborators (perhaps Francesco Botticini) would be responsible for the rocks on the sides, that the latter’latter would later have been succeeded by Botticelli, and finally that the whole was harmonized by Leonardo da Vinci, who intervened first to eliminate, as seen above, the rock wall on the left (some element of the primitive drafting emerges under the last pictorial layer) and to complete the figures. However, it is entirely plausible to imagine that more than one author put his hand to the painting: it will be useful to recall also the presence, on the back of the painting, of some drawings, quick sketches that are apparently not attributable to any of the authors who intervened on the painted part, and that could belong, according to Antonio Natali, to an artist from Verrocchio’s workshop fascinated by the dynamism of Piero del Pollaiolo’s figures, to whom these sketches seem to look with some insistence.

However, it is precisely the blond angel that is the element in the painting that offers the possibility of directly comparing Leonardo da Vinci’s painting to that of the painter who dealt with the other angel, thus probably Botticelli. The angel on the left is in fact painted with a diffuse light found only in this figure, with one of the earliest known applications of Leonardo’s sfumato (the subtle transition from one gradation of light and color to another, with the contours of the figure blending into the atmosphere and no longer marked more or less sharply as was previously the case), and with "an almost impressionistictouch,“ scholar Martin Kemp has written, that does not ”literally sculpt the forms,“ but aims, if anything, to ”emphasize brightness, refraction and reflections." The divergences can be clearly seen when looking at the hair of the two angels: while that of the right-hand angel is defined with the precision typical of a goldsmith, Leonardo uses reflections of light to bring the angel’s hair to life ("when Leonardo intervened with oil glazes to cover the surfaces of the water in the foreground and background of the Baptism,“ Kemp pointed out, ”he rendered them with a mixture of optical vitality and intrinsic life of form. No subject, static or moving, remained inert under the touch of his brush or pen."). It is easy to observe how brightly the blond angel’s hair shines, and how full of life his face is, compared with the brown-haired brown angel, who though more expressive does not have the same softness as his companion painted by Leonardo da Vinci. But there are also obvious differences between Jesus and the Baptist, with the former being more softly modeled than the latter.

Leonardo’s angel then represents an overflowing novelty on the iconographic level as well. With his angel, Leonardo demonstrated, Gigetta Dalli Regoli has written, “how one can, with decision but also with grace, unhinge an iconography established by long tradition: Devoid of wings (the static setting of the subject imposed it), and perhaps originally even of a halo, an enchanting androgynous teenager enters the scene turning his back on the audience, but immediately captures their attention by twisting, showing at once his beautiful face and shiny hair, with the consequence of irreparably blurring his companion.” And again, the scholar, in a text now in press, returns to the subject of the angel’s iconography, reiterating that such an innovative invention could only have been induced by “a strongly critical impulse” and “a reasoned choice,” to arrive at that “awkward pose, blatantly artificial, but at the same time a solution that demands strong visibility.”

The painting met with wide appreciation, so much so that it was much copied: the best-known derivative version, as a faithful witness to the initial layout of the painting by Verrocchio and Leonardo, is probably the one preserved in San Domenico in Fiesole, one of the oldest known, made by Lorenzo di Credi more than twenty years after the Uffizi panel. Then there is also a singular translation into ceramics, the work of Giovanni della Robbia, who several times used the work of Verrocchio and Leonardo da Vinci as a source of inspiration: see, for example, the tile of the baptismal font in the church of San Pietro in San Piero a Sieve, which is its most faithful transposition.

After decades of study, hypotheses have also been put forward about the possible history of the painting: it would have been commissioned from Verrocchio around 1468 or perhaps even some time earlier, although this may be the most likely terminus a quo, or initial point of reference, since it was precisely in 1468 that Verrocchio’s brother Simone di Michele had become abbot of the monastery of San Salvi, where the work was located in ancient times, and may therefore have allotted it to the master. We have no certainty, however, that the work was commissioned specifically for San Salvi, despite the hypothesis being plausible. In any case, Verrocchio would have begun the painting and then entrusted it to his numerous collaborators, some permanent, others temporary: when the work was resumed, probably around 1475, the master would have entrusted the young Leonardo da Vinci with the task of completing the missing parts and then unifying everything once the work was finished.

Finally, if for decades scholars have been questioning who did what inside the painting (a question that, however, as we have seen, now has almost established answers), more recent, on the other hand, are the attempts at iconological interpretations of the painting. The first to hypothesize that behind the Baptism of Christ was a patron of solid theological culture was Antonio Natali, who in a hypothesis formulated in his 1998 essay, and then substantially confirmed in 2013 by scholar Giorgio Antonioli Ferranti, linked some motifs in the painting to the Golden Chain of St. Thomas d’Aquinas, the commentary on the Gospels by the Doctor of the Church that was first printed, in Rome, precisely at the time when Verrocchio’s and Leonardo’s work was perhaps beginning to take shape, namely in 1470. Leonardo was certainly familiar with Aquinas’s work (the title “Golden Chain” is also found in one of the sheets of the Arundel Codex), and several references to St. Thomas’s commentary would be found in the painting, particularly those underlying the participation of the Trinity in Baptism (the hands of God, moreover, represent an Augustinian concept reiterated by St. Thomas Aquinas: the final opening of the heavens, which had closed because of original sin, after the fundamental event of baptism), the fleeing hawk, and the stones symbolizing the Church instead. For Thomas Aquinas, the dove, an animal “simplex et laetum,” is a peaceful bird because it does not have claws that tear, just like the saints who love concord, and as opposed to the heretics who instead tear doctrine: hence the presence of the bird of prey. And again, we read in the Golden Chain that at the moment of baptism, the Holy Spirit himself descends on the Church to prepare the future baptized to receive him: the dove and the river stones are thus closely related. Finally, Natali proposed to identify in the figure of the right angel the archangel Michael, who was attributed a psychagogical function, since he was entrusted with the task of accompanying souls to Paradise, at least according to the apocryphal writings.

Apart from the hypotheses of Natali and Antonioli Ferranti, there have been no other attempts at iconological interpretation. Leonardo da Vinci was after all a believing artist, but also a strongly innovative one, and it therefore becomes difficult to imagine him slavishly following an iconographic tradition, or faithfully reporting in images the text of a Doctor of the Church: on the contrary, the Da Vincian, while moving within the schemes of his own time, proved to be a strong innovator of the iconographic customs of his time. One need only think of the dialogue of gestures and glances that animates the Virgin of the Rocks, or the recurring element of the finger pointing upward that has yet to be fully elucidated and that appears, for example, in the Baptist of the Louvre and the Saint Anne of the National Gallery in London. There is no exception, for example, to the angel from behind, which precisely in the pose, as we have seen, finds its most innovative element.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.