Walking through the streets of Arles, France, one is sure to find oneself inside a Vincent van Gogh painting at some point. Not by imagination or one of the many immersive exhibitions dedicated to the famous Dutch painter. In fact, at number 11 Place du Forum in Arles you will still find the café that inspired one of his most important masterpieces: Café Terrace in the Evening, Place du Forum, Arles, now preserved at the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo. Today Café Van Gogh has become one of the iconic places for those who visit the French town, and stopping by sitting at the tables in the shade of the distinctive yellow canopy is now a must, and it is amazing how similar the two juxtaposed images, i.e., Van Gogh’s painting and a photo taken in the present day at that very spot, are, of course with due proportion, since a time span of more than one hundred and thirty years runs between the two. Vincent van Gogh (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890) stayed in the Arles region between February 1888 and May 1889 in search of a new, intense light and brilliant colors, and during his stay he produced about three hundred works, including paintings and drawings. Arlesian was his most prolific season. In the town it is possible to walk a true pedestrian circuit dedicated to the artist, marked at the various stops by the paintings related to them: there are about ten in all, and among them is the Café at Place du Forum.

The painter imprinted it on canvas one September evening in 1888, while he was strolling as he was wont to do through the streets of the city, with his easel always with him. Following the lesson of the Impressionists, the artist in fact painted directly on the spot, in this case in theopen air, transferring to canvas what his eyes actually saw at that moment. So that evening he must have stopped to observe that yellow-roofed café overlooking the Place du Forum with its dehors and the customers sitting alone or in company at the pretty white tables lit by the enveloping yellow light of the gas lamp hanging in the center. Below the light source, a waiter was taking orders at the tables. He must have noticed that the perfect row of tables on the street was completely empty and that the shutters on the windows above the café were still open. A few people were still strolling on the cobblestone street, and in some of the apartments the lights were still on, as they were in the corner diner across from the café. It was a magnificent starry night: everything was so perfect that one had to paint that urban glimpse as it was, standing in the background, almost in the distance. The people do not turn out to be defined in their faces, only their silhouettes can be perceived, but the light from the gas lamp must have been really strong, so much so that even the outside wall of the café looked yellow, instead of blue as can be seen from the part of the door in the foreground on the left and from the upper floor of the building. And the stars, too, must have been very bright that evening, from the way he depicted them large and disproportionate, so much so that one could perceive their yellow core and the white halo around them.

Van Gogh had long wanted to paint a starry sky: a letter written to his sister Willemien on September 9 and 14, 1888 reads, “I absolutely want to paint a starry sky now. It often seems to me that the night is even more richly colored than the day, colored with the most intense purples, blues and greens. If you look closely you will see that some stars are lemon colored, others have a pink, green, blue glow.” The painter resumed writing the same letter a few days later, as he himself explains, because he was busy precisely in the making of Café Terrace in the Evening: “I was interrupted precisely by work these days on a new painting of an exterior of a café in the evening. There are little figures of people drinking on the terrace. A huge yellow lantern illuminates the terrace, the facade, the sidewalk and also casts light on the cobblestones of the street, which takes on a pink-purple hue. The facades of houses on a street receding under the star-studded blue sky are dark blue or purple, with a green tree.” And he points out how he painted a nocturne without using black, but only “a beautiful blue, purple and green, and in this setting the illuminated square is colored pale sulfur, lime green.” “I like very much to paint on the spot at night,” he confesses in the letter to his sister. "It is very true that in the dark I can mistake a blue for a green, a lilac blue for a lilac pink, since you cannot clearly distinguish the color. But it is the only way out of the conventional black night illuminated by a pale, whitish light, when in fact a simple candle gives us the richest yellows and oranges." The work is indeed unconventional, as the night is depicted not in shades of black or dark gray, but with an abundance of colors: above all blue and yellow. In fact, what stands out in the painting is the strong contrast between warm colors, such as yellow and orange, under the canopy, and cold colors, such as blue and purple in the buildings in the background and in the sky.

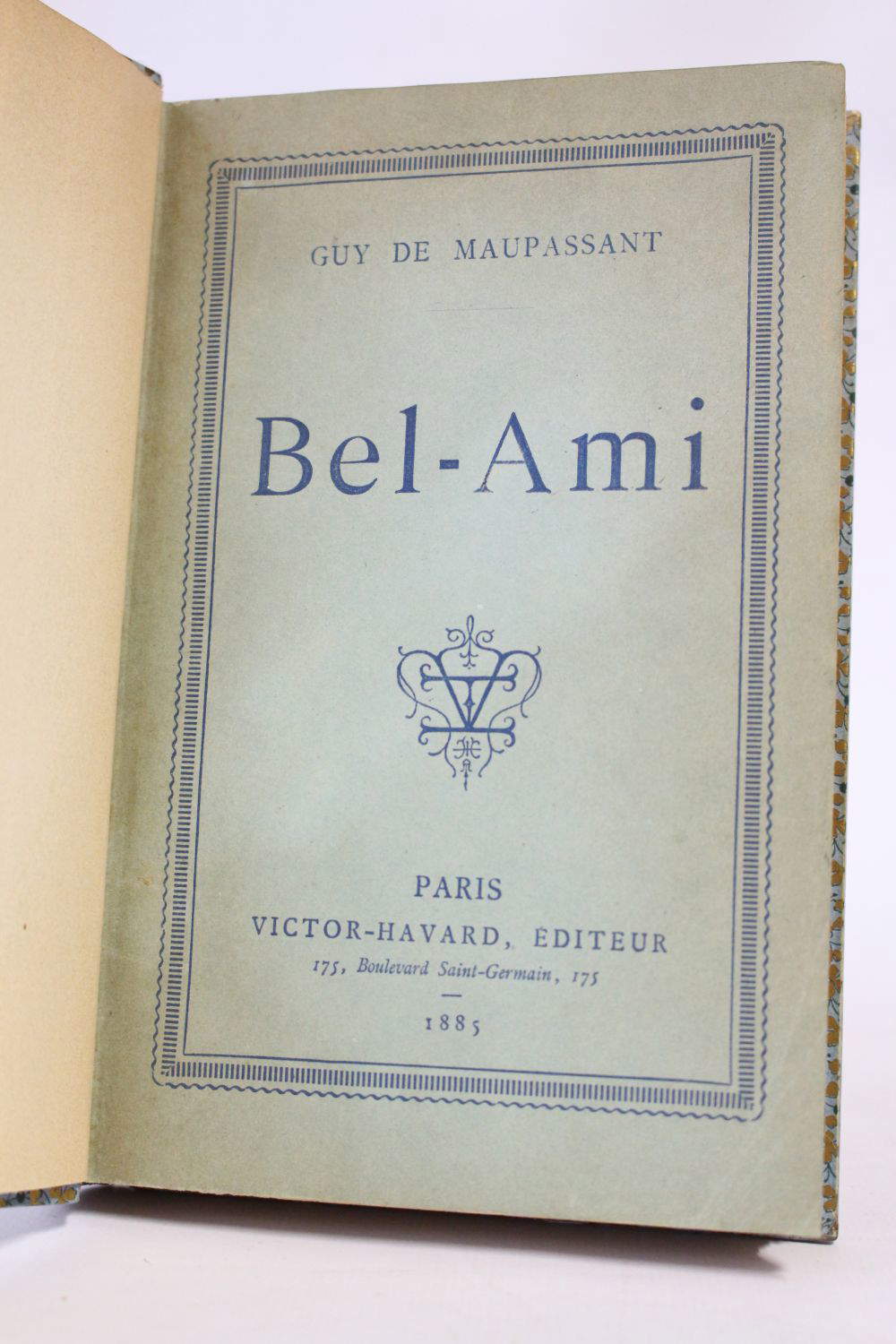

In the same letter, Vincent asks his sister Willemien if she has ever read Bel-Ami by Guy de Maupassant, published in 1885, and what she thinks in general about his writing. "I say this because at the very beginning of Bel-ami there is a description of a starry night in Paris, with the cafes lit up on the boulevard, and it is a bit like the same subject I painted just now." In fact, the protagonist of Maupassant’s novel, George Duroy, passes, at the beginning of the story, in front of cafés full of people who display their drinking clientele under the powerful light of illuminated facades. Painting directly on the spot at night attracted the local press, so much so that the Chronique artistique et musicale reported on September 30, 1888, that “Mr. Vincent, an Impressionist painter, works, we are told, in the evening, by the light of gas lamps, in one of our squares”; indeed, as already stated, van Gogh was very fond of painting during his night walks through the city streets: “I find it convenient to paint the thing at once. In the past artists would draw and then during the day they would make the picture from the drawing.” There is, however, an accomplished drawing by the artist, now housed in the Dallas Museum of Art, which reproduces almost exactly the painting in question, also dated September 1888.

The painting is further described by Vincent in a letter to his brother Theo dated September 16, 1888 as "the outside of a café, lit on the terrace by a large gas lamp in the blue of the night, with a glimpse of a starry sky." After this glimpse, the painter painted other starry skies, considered among his most iconic paintings: in fact, shortly afterwards is Starry Night on the Rhone, now at the Musée d’Orsay. In fact, it dates from about September 29, 1888, the letter to his brother Theo in which he describes the famous masterpiece: “the starry sky painted at night, under a gas lamp. The sky is blue-green, the water is dark blue, the earth is mauve. The city is blue and purple. The gas light is yellow and its reflections are red gold and slope to bronze green. In the blue-green sky the Great Bear is a shimmering green and pink, whose pallor contrasts with the brutal gold of the gaslight. Two figures of lovers in the foreground,” and the description is accompanied by a small sketch of the painting for his brother to preview. And June 1889, on the other hand, is MoMA’sStarry Night in New York, this one, however, made in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. In fact, he calls it “a new study of a starry sky”: the extraordinary dynamic effect Vincent creates in the sky, punctuated by large stars, the so-called “morning star” and the moon, is in fact the result of a mixture of reality and imagination, or rather, it is an expression of a state of mind, unlike the Arlesian starry sky, which intends to represent only reality.

As with Starry Night and Starry Night on the Rhone, for Terrace of the Café in the Evening, Place du Forum, Arles, astronomers sought to identify the stars in the painting to confirm its date. Astronomer Ed Krupp of the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles has ascertained that Starry Night was made on June 19, 1889, as he and Albert Boime recreated the 4 a.m. starry sky of that date, noting its striking resemblance to the one painted. Donald Olson used the Big Dipper seen in Starry Night on the Rhone to determine that Van Gogh made it on September 26 or 27, 1888 on the banks of the Rhone around 10 p.m. local time. Concerning the Café Terrace in the evening, astronomers are fairly unanimous in confirming the starry sky of September 16 or 17, 1888, with the exception of the aforementioned Olson, who states that the constellations mentioned in the studies dealing with the painting are actually not accurate. Indeed, if the date advanced (Sept. 16-17) by astronomers was correct, how could it be possible that Van Gogh interrupted the letter to his sister Willemien (dated Sept. 9-14) and then resumed it after a few days, as he himself admits, to make that very new painting?

Beyond these considerations, Café Terrace in the evening reflects precisely theunconventionality of a “colorful” and bright night. “It often seems to me that the night is much more richly colored than the day,” Vincent van Gogh wrote in the same letter to his sister. The intense yellow of the gas light creates an extraordinary variety of shades in the painting with its reflections on facades, cobblestones and everything it encounters in its beam. And of the dark, black night not even a shadow.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.