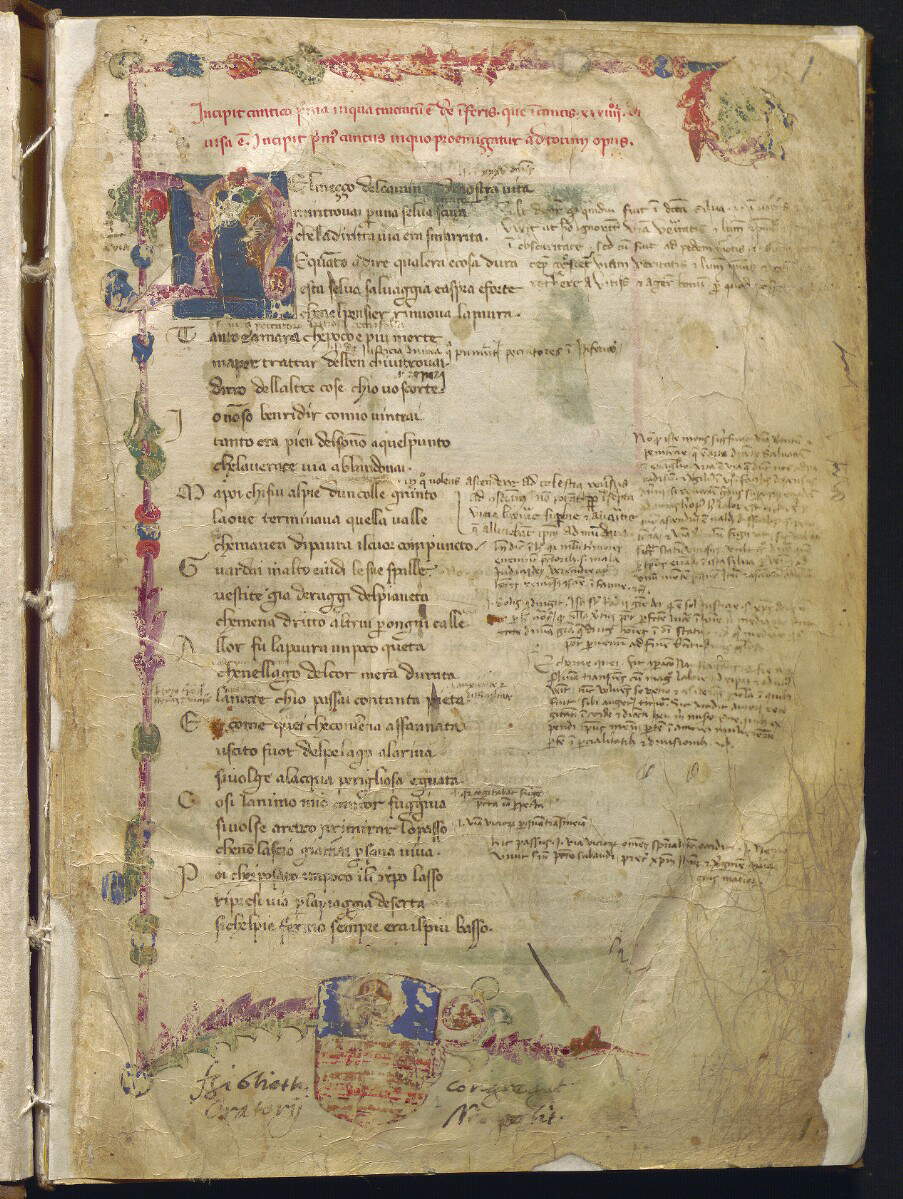

Preserved at the Biblioteca Statale Oratoriana dei Girolamini in Naples is what is believed to be the oldest example of Dante Alighieri ’s Commedia circulating in the Neapolitan city that has come down to us. It is a work presumably executed in the 1450s in Naples itself, although a number of Florentine personalities contributed to the creation of the work, who collaborated with illuminators from a Neapolitan workshop, who enriched the text with no less than one hundred and forty-six miniatures illustrating the salient moments of Dante’s journey between Hell, Purgatory and Paradise. The Divine Comedy of the Girolamini also figures among the earliest witnesses of the text’s fortunes outside Florence, and is known, in addition to its marking CF 2.16, also as the Dante Filippino, due to the fact that the library of the Girolamini belongs to a complex founded by members of the Congregation of the Oratory, followers of St. Philip Neri (after whom, moreover, the complex itself is named: the name “Girolamini” derives instead from the fact that the first Oratory of Philip’s followers had been established at the church of San Girolamo della Carità in Rome).

A fortune that, moreover, the Comedy had begun to reap not long ago: on the occasion of the exhibition Honorable and Ancient Citizen of Florence. The Bargello for Dante, held at the Bargello Museum in Florence in 2021 to mark the seventh centenary of Dante’s death, scholar Francesca Pasut suggested that it was from 1337, the year in which in the Cappella del Podestà the image of Dante, painted by Giotto, made its appearance among the blessed in Paradise, that the idea of "make the Commedia not only a book sought after, read or studied by a heterogeneous public, but also an illustrated volume, provided with eloquent images, more or less cleverly related to the text, and this with the contribution of the many Florentine artists specialized in the field of book decoration." The Naples Codex, too, thus represented a publishing enterprise that was part of this context of producing luxury editions of the Commedia, intended for a demanding clientele, and which were at first exclusive to Florence, the prmary center of production of works of this kind, and later spread to other Italian cities.

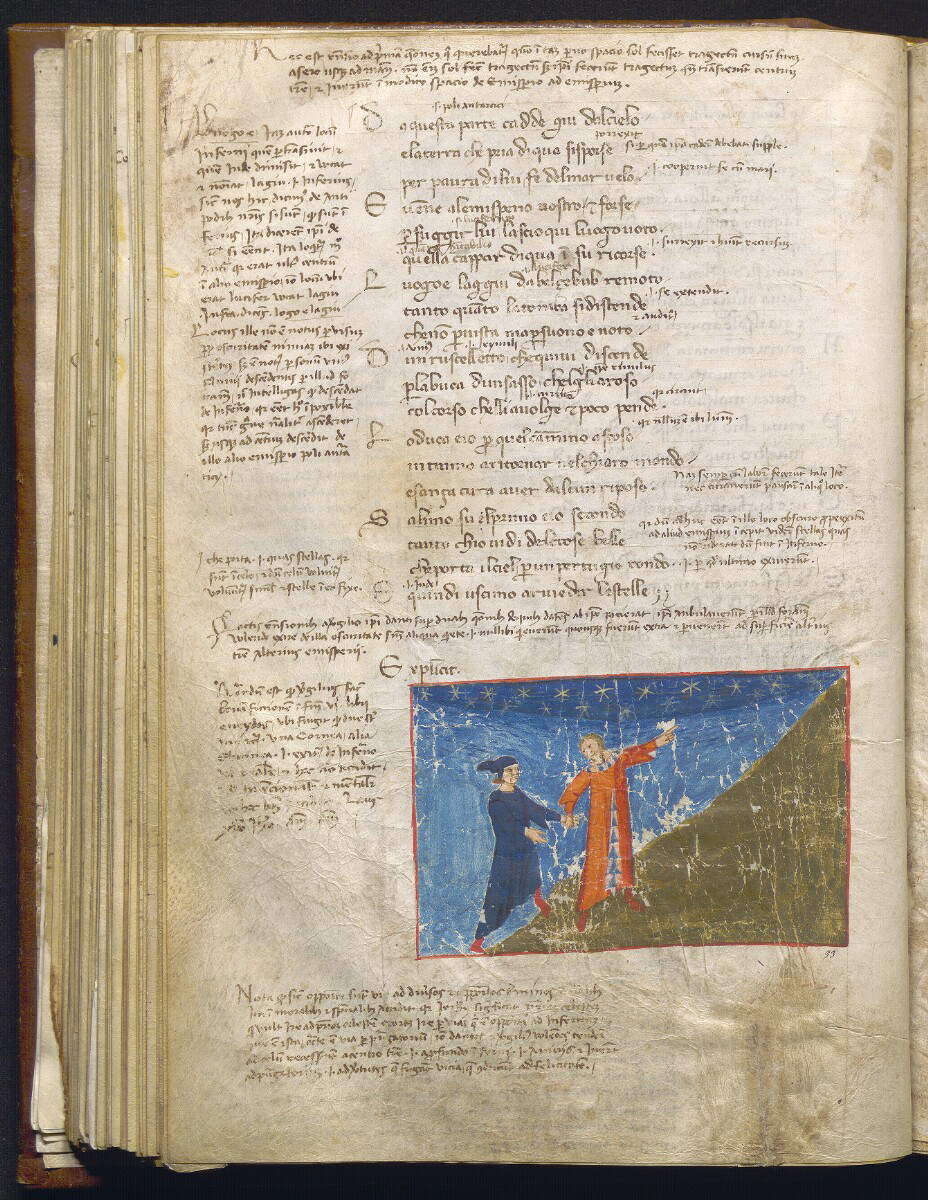

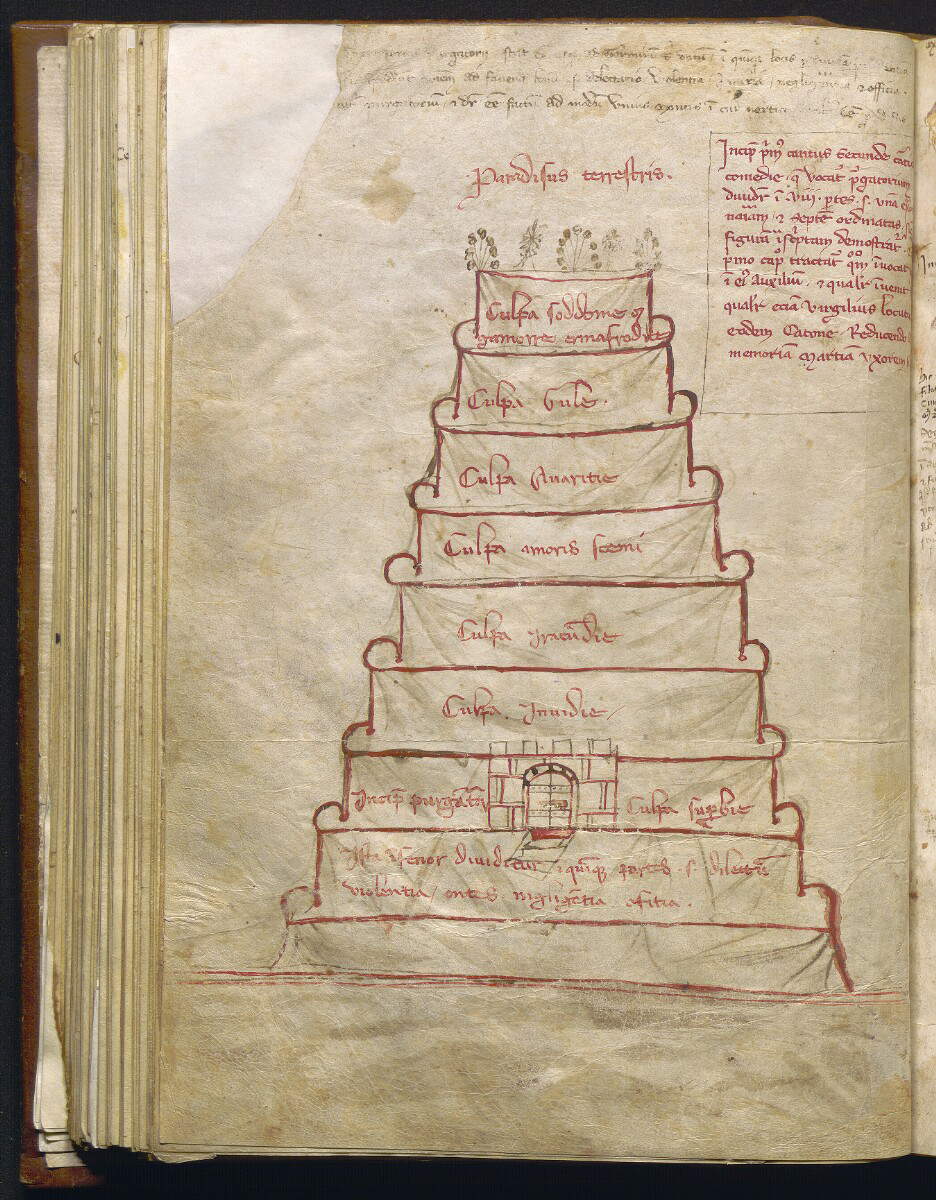

The oldest specimens of this tradition are those that are part of the so-called group of "Danti del Cento,“ a locution that indicates, Pasut goes on to explain, a ”compact nucleus of manuscripts, identified in part on philological grounds, but above all for their graphic and codicological characteristics, which are replicated from specimen to specimen in codified form.“ The oldest attestation of the expression ”Danti del Cento“ is found in a fifteenth-century manuscript where ownership of a codex is claimed: ”Questo Dante de’ ciennto è di me Domenicho di Carlo Aldobrandi et chy l’achatta da lui sia contento di rimandarlo presto.“ The term ”hundred“ thus most likely indicates the centuries-old antiquity of the manuscript. Then there is a famous anecdote, recounted in the sixteenth century by Vincenzo Borghini, that it was only one amanuensis who copied ”one hundred Danti" in the fourteenth century: in reality, this activity involved a far greater number of copyists. The Dante Filippino, for some of its characteristics, such as the graphic typology, can be approached to the group of the Hundred Danti, but different is the pagination (the Neapolitan codex is in fact presented with text on a column), and different is also the decoration that goes far beyond the cantica initials. In addition, it should be specified that Dante Filippino ’s undertaking was not completed in a unified manner: it is in fact a luxury product only for Inferno and Purgatorio, while the same cannot be said of Paradiso, which is almost completely devoid of illustrations.

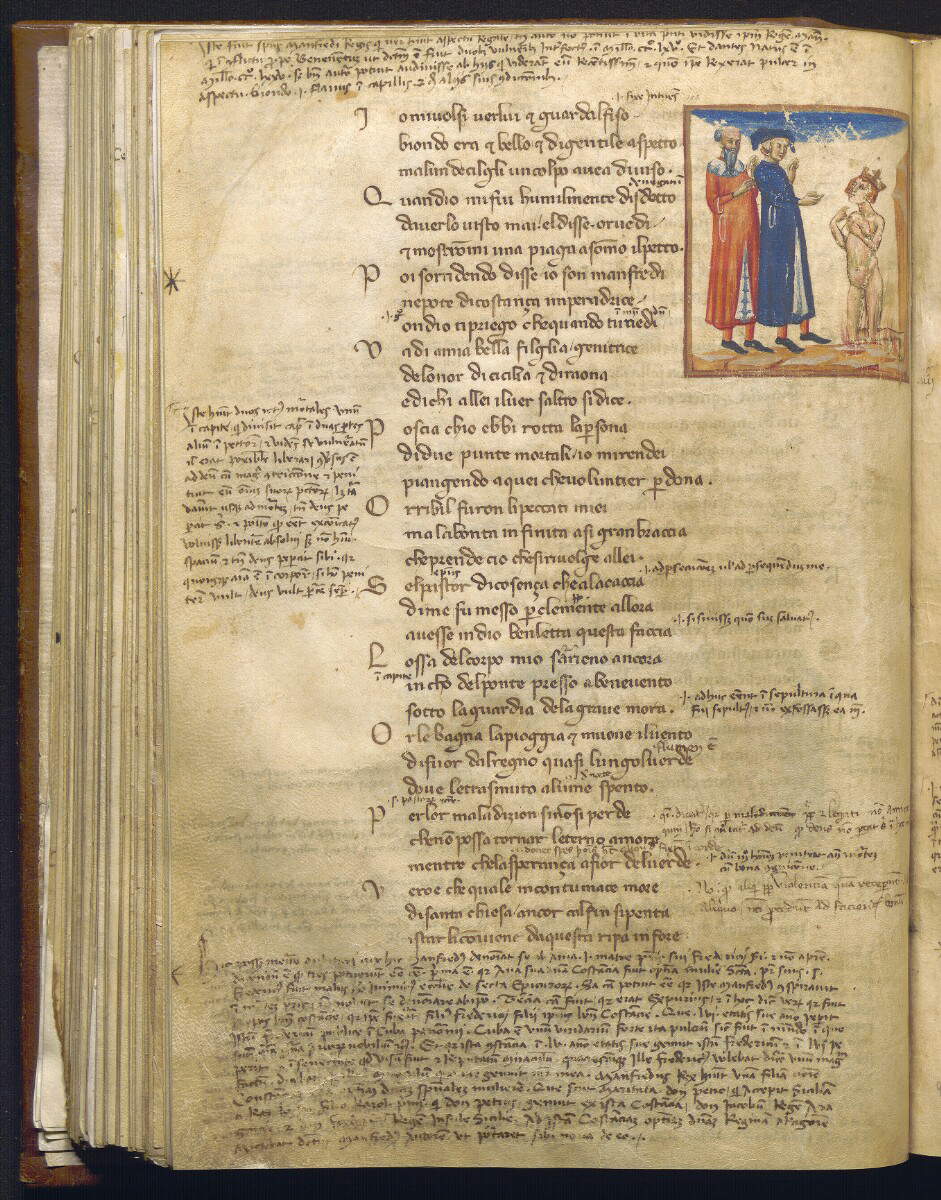

We do not know for sure for whom this edition of the Comedy was produced: the most likely hypothesis is that the addressee was a jurist named Lorenzo Poderico, born in Naples in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, a member of one of the most illustrious families of the Neapolitan nobility, rector of the Studio of Naples (the ancient university) from 1351 to 1358, the year of his death, and famous for being one of the most learned men of his time. He was also a prominent politician, since he served as adviser to the young Queen Joanna I of Anjou. In fact, the first paper of the manuscript bears the coat of arms of the Poderico family, although this is not decisive evidence: it may also mean that the Poderico family, at some point in history, owned the manuscript. A hypothesis has then been put forward that the marginal notes found in the text are referable to Lorenzo’s hand. The fact that annotations and postille are present is an indication that this edition of the Commedia, despite being conceived as a luxury product, had nevertheless served the function of a scholarly tool.

Divine Comedy

Divine Comedy

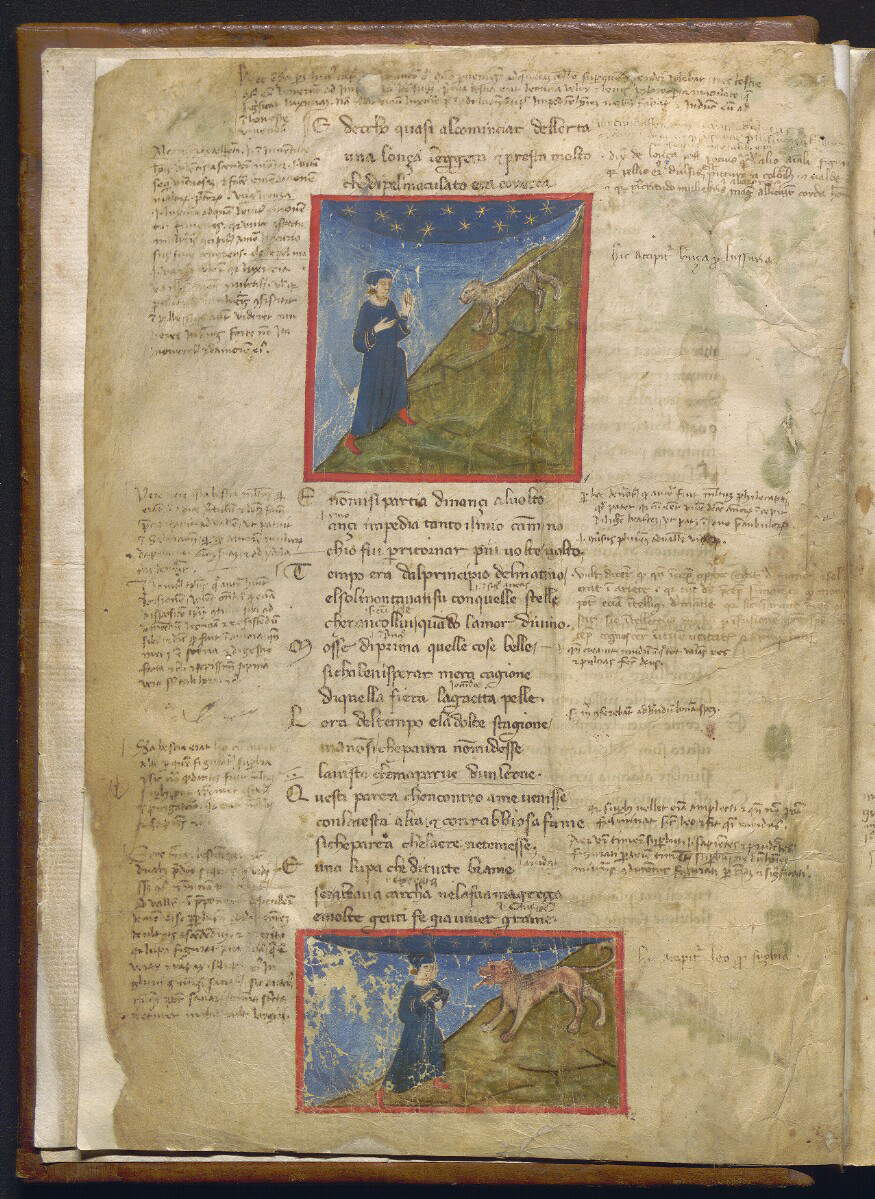

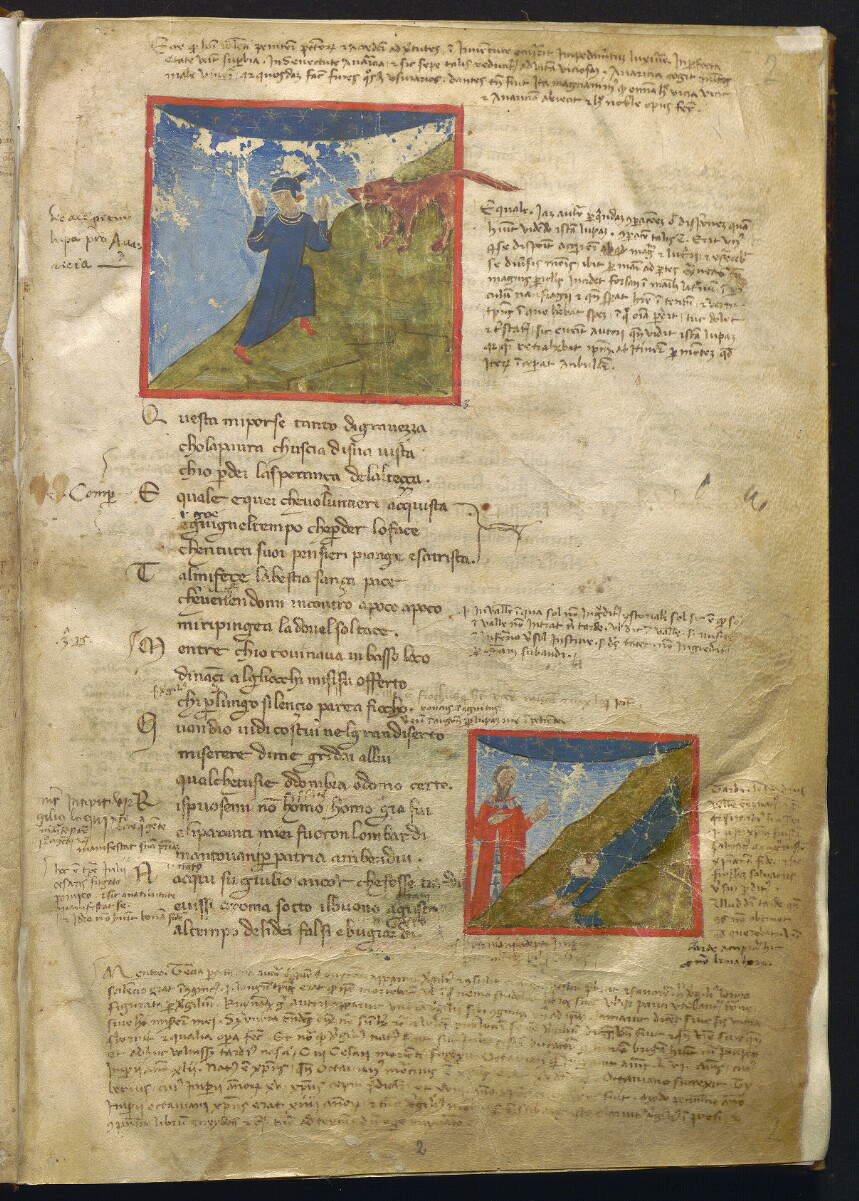

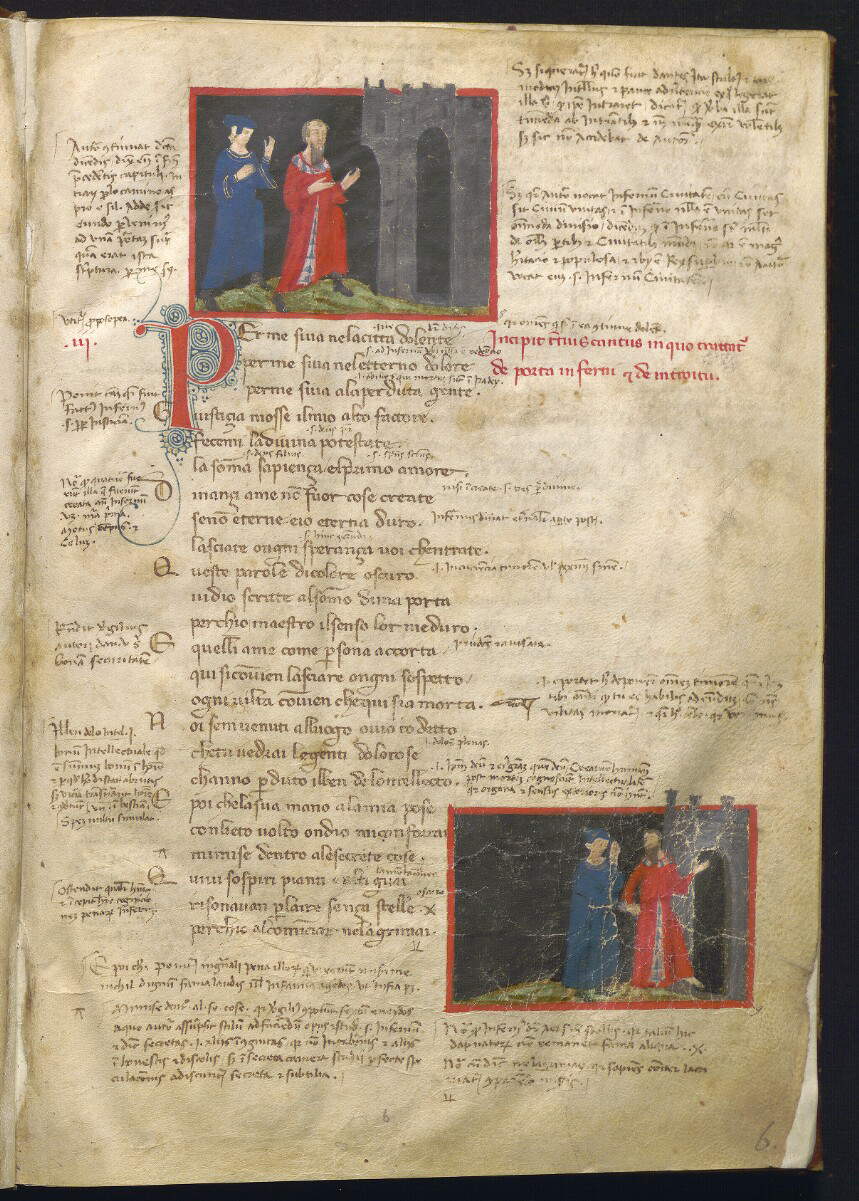

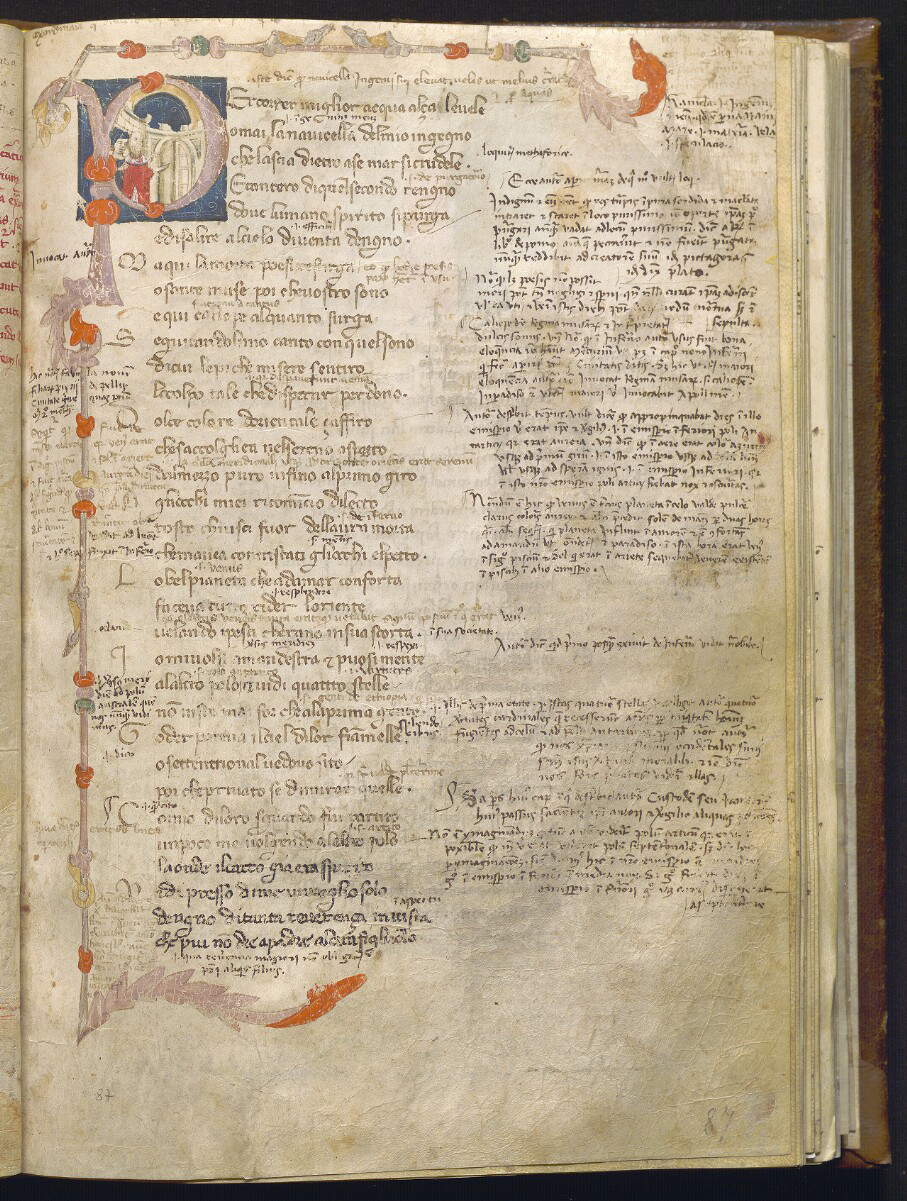

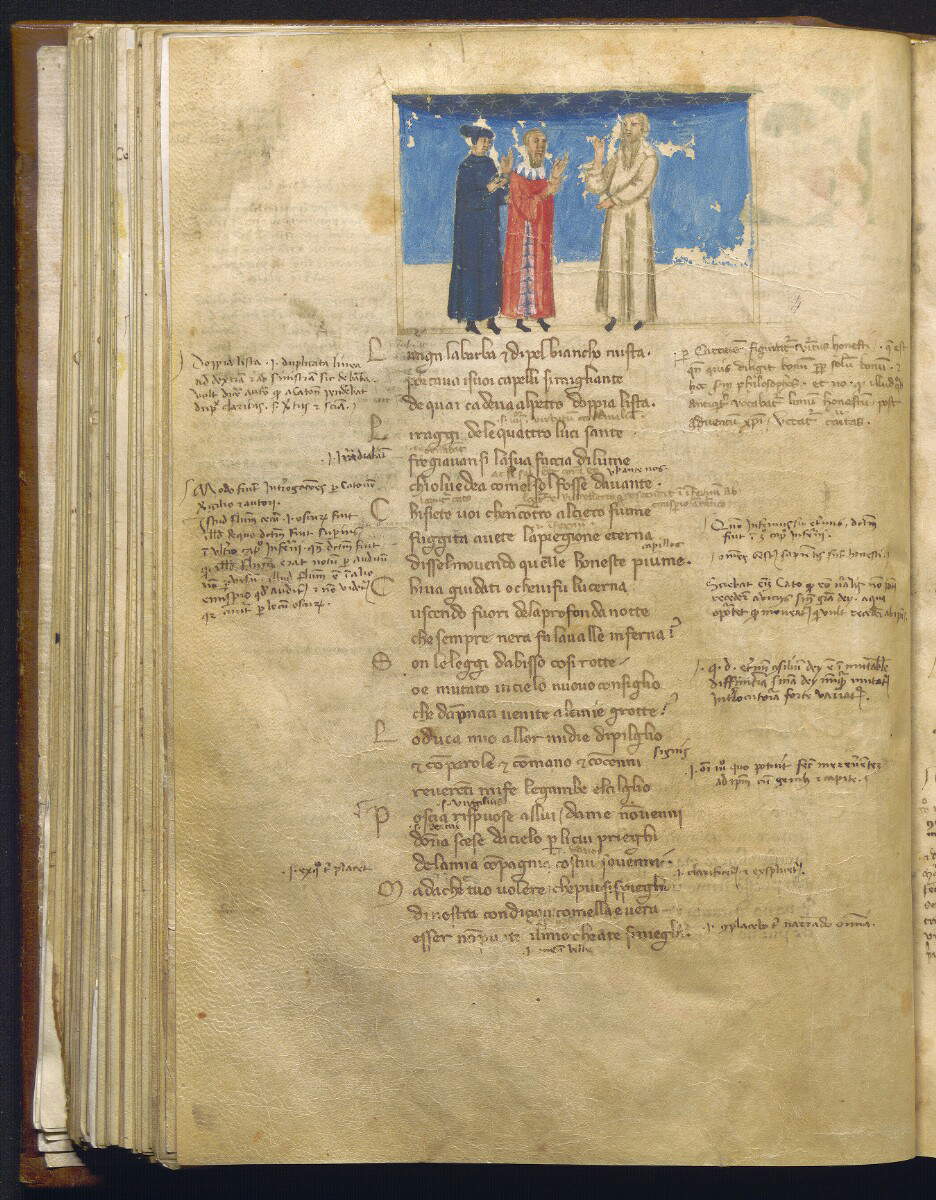

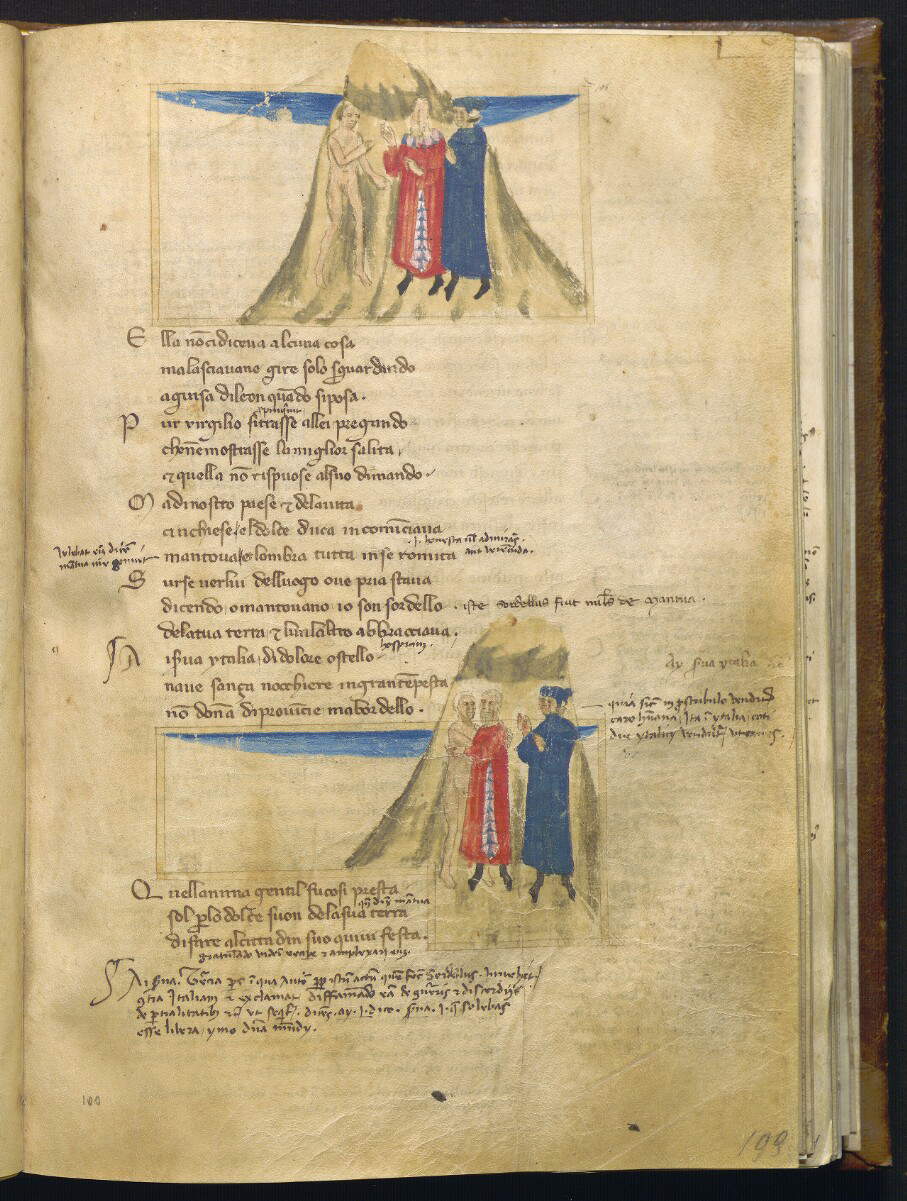

The literary historian Gianfranco Contini identified about ten different hands among the pages of the codex, seven of copyists and three or four of illustrators, although originally the scribe who took care of the writing of the text was only one, to whom are attributed the papers ranging from 1 to 239, written in chancery lowercase (the other hands are those who mostly added the notes in the margins). The other hands partly extended the original draft (epitaphs for Dante were in fact added), and partly merely annotated. We can guess that some of the glossators, from the way they wrote, were Florentines. However, we do not know the place of transcription, nor the date of completion (there are no dates in the codex), nor who were the glossators who annotated the codex in the margins. We do know that it was certainly reworked, since the binding is from the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. Given the homogeneity of text and images, however, it is possible to assume that copyist and illuminators worked in close contact. In fact, each paper that makes up the Dante Filippino features at least one illustration, but in some cases there are even two or three per paper.

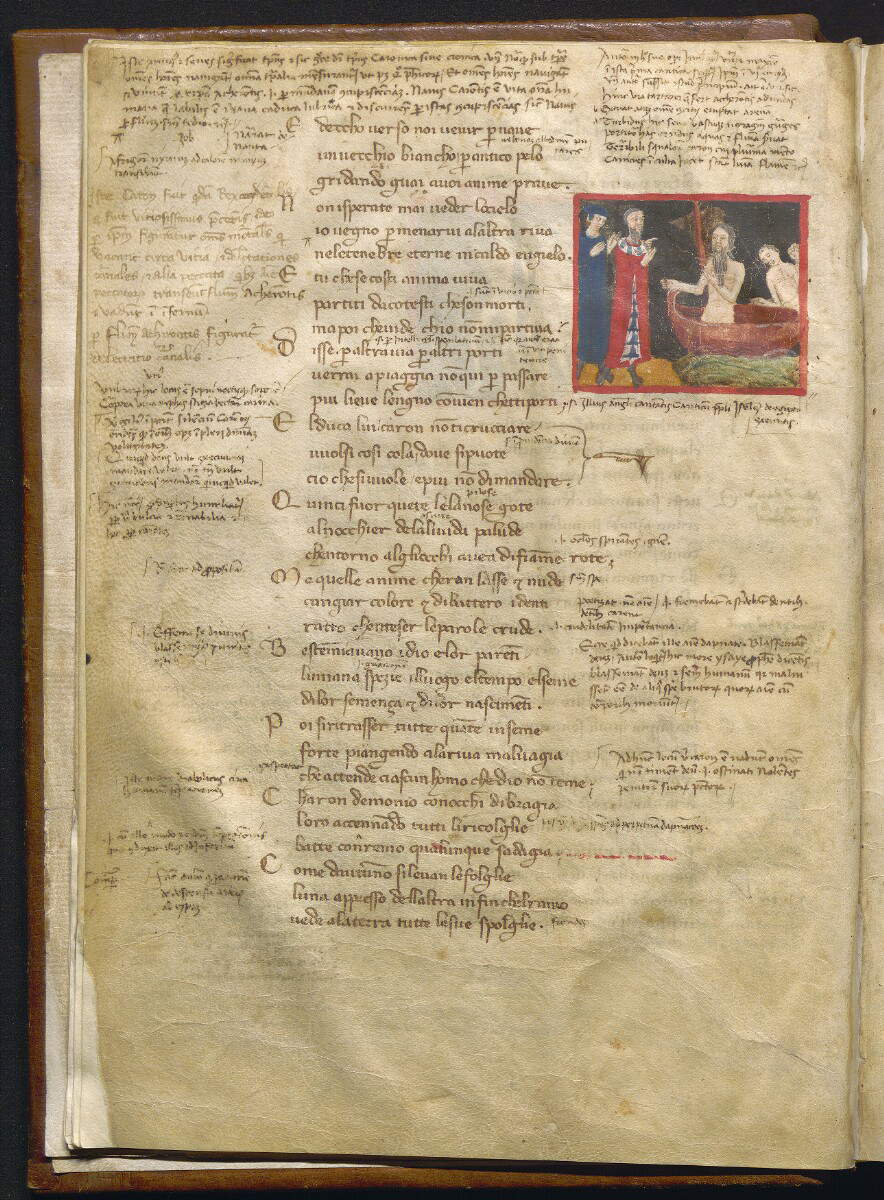

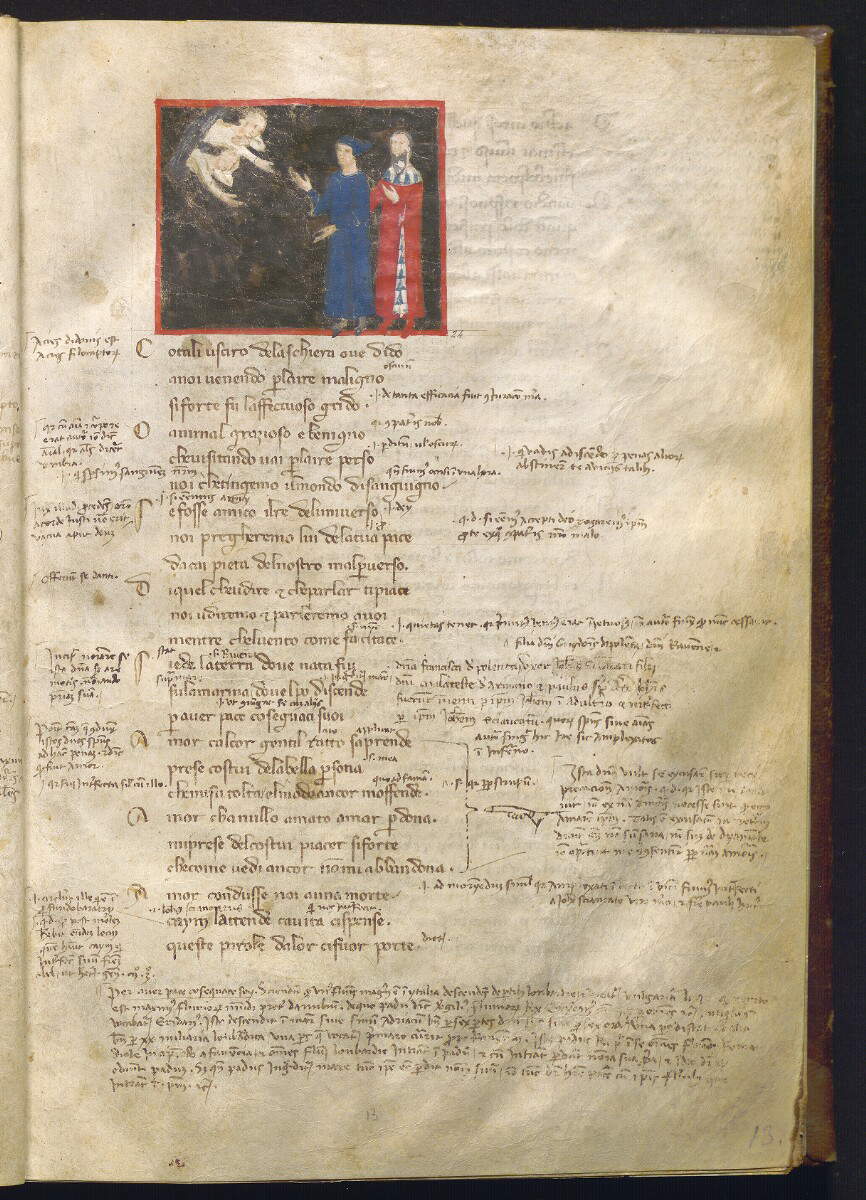

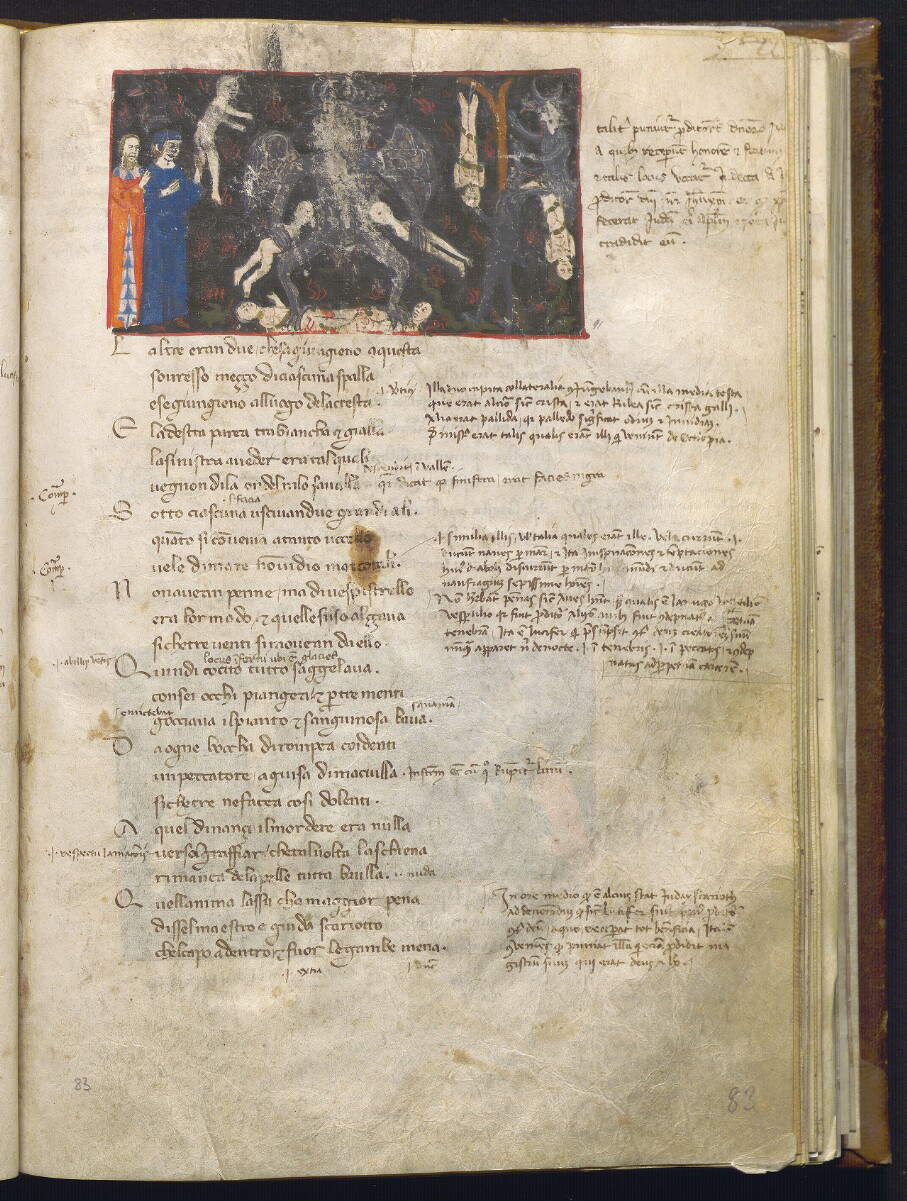

Despite the richness of the iconographic apparatus, however, the illustration of the Dante Filipp ino does not stand out for its originality and quality: there are few truly interesting images (among them, for example, the scene with Lucifer), while repetitive, naive, schematic, paratactic figurations prevail, where, moreover, more often than not the figures, slender and poorly proportioned, move against monochromatic backgrounds (see, for example, the paper where the episode of Paolo and Francesca is depicted, but the same could be said for almost the entire manuscript). The interest of the Dante Filippino lies mainly in the desire on the part of its authors to illustrate Dante’s verses with continuity, and in the fact that it nevertheless figures among the oldest witnesses to the Commedia, as well as to a precise publishing tradition.

Finally, we do not know in detail all the transitions of ownership that affected the codex, nor do we know when and how the Dante Filippino came to the Girolamini Library: in fact, it appears for the first time in the catalog compiled by Giambattista Vico in 1726, in which, however, no information is given about the provenance of the volumes. It is possible that the manuscript was part of the collection of Giuseppe Valletta (Naples, 1636 - 1714), a philosopher and jurisconsult who was a prominent figure in late 17th-century Naples, “to whose cultural renewal,” wrote scholar Loredana Lorizzo, “he contributed by forming a rich library of more than sixteen thousand printed volumes and manuscripts, which offered intellectuals of the time a wide panorama of contemporary European literature.” After his death, part of his collection went on to form, at the very suggestion of Giovanni Battista Vico, the founding nucleus of the Girolamini Library. This unique fourteenth-century manuscript could thus ideally unite three important figures of Italian culture.

The Biblioteca Statale Oratoriana dei Girolamini (formerly known as the Biblioteca Pubblica Statale Oratoriana del Monumento Nazionale dei Girolamini) is located in the Oratorio dei Girolamini in Naples, and is one of the oldest institutions in Italy (as well as the oldest in Naples) since it was opened to the public in 1586, contrary to the customs of monastic orders, which did not allow the public to enter their libraries. Among those who frequented it was the great philosopher Giambattista Vico, who, in 1727, suggested that the Oratorians purchase the book collection of jurist Giuseppe Valletta, which included a collection of legal, philosophical, religious and literary texts from 17th- and 18th-century Naples. The Library has remained virtually intact over the centuries, now dependent on the Ministry of Culture, and is housed in four splendid 18th-century and two modern rooms of the extraordinary Girolamini monumental complex.

The library holdings of the Girolamini Library amount to about 159,700 units of volumes and pamphlets, including 137 musical printed books, 5,000 16th-century editions, 120 incunabula, 10,000 rare and valuable editions, 485 periodicals, an as yet undetermined amount of microfilms and portraits. Among the most important holdings are the Agostino Gervasi Fund (5,057 volumes), whose texts deal with archaeology, numismatics, bibliography and classical literature; the Filippino Fund, mainly on ecclesiastical history, sacred scripture and theology; the Giuseppe Valletta Fund, containing rare editions from the 16th and 17th centuries consisting of Latin and Greek classics, history and philosophy; and the Valeri Fund (940 volumes), with books dealing with the history of Naples and southern Italy.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.