The most extravagant child of the Renaissance: the Portrait of a Child by Giovan Francesco Caroto

Never before has there been such an unconventional portrait of a child in Italian Renaissance painting: the Ritratto di Fanciullo con disegno (Portrait of a Child with Drawing ) by Giovan Francesco Caroto (Verona, 1480 - c. 1555) is considered, in addition to being his most famous masterpiece, a unicum, because the subject depicted in the foreground seems to address anyone looking at him directly with alaughing, lightheartedexpression as he contentedly shows off his drawing. A childish drawing of the kind that all children enjoy and undertake to make on a simple sheet of paper and which, when finished, they proudly show to adults, to their parents, to have them tell them how well they did. Indeed, this seems to be the scene we see painted: the adults the little boy is addressing are us, all the people who over the course of time have had occasion at least once to pause in front of one of the most famous portraits in art history, while the little boy is a sixteenth-century child. The smile may have been slightly sketchy (think of the one in Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, a work datable between 1503 and 1506), but a half-open-mouthed smile that even allows a glimpse of the upper arch of the teeth was very innovative, just as unconventional was that direct and explicit address to the viewer inviting him or her to give his or her own opinion on the drawing shown. Indeed, an interaction is created, an exchange involving three elements: the subject portrayed, the observer and the very object of that invitation, namely the drawing.

However, the identity of the child is not yet known with certainty: it could be the painter’s son Bernardino, born in 1505 or 1507, who was motherless and later became an apothecary in the family-owned apothecary shop with his father from 1529, or his nephew Giovan Pietro, also a painter and called Centenario, born around 1503; the latter worked in the family workshop and in the registry of 1531 appears to be cohabiting with his uncle Giovanni Caroto. It is certain, however, that this was a real person and familiar to him.

With long, straight red hair combed with a parting in the middle, the boy is depicted in the foreground, in profile and half-length against a dark background; he has an oval face, large brown, viscous eyes framed by fine, arched eyebrows, slightly flushed cheeks, and a half-open-lipped smile from which his teeth are protruding. He wears a green farsetto over a white shirt and probably holds a red cap in his left hand, the fabric of which appears in the lower left margin of the painting. His age is between ten and twelve. With his right hand he holds facing the viewer a sheet of paper on which he has drawn with very childlike strokes a fairly disproportionate human figure with a large head, small body, and thin, long arms and legs.

Giovan Francesco Caroto made the Portrait between 1515 and 1520, but the work is not mentioned in Vasari’s Lives . It is first mentioned in the inventory of Antonio Maria Lorgna ’s Verona collection given to Count Giovanni Emilei in 1781, as a “Quadretto d’un giovane ridente con bamboccio in mano della scuola precisa del Correggio.” In the 19th century it is attested in the collection of Cesare Bernasconi and attributed to Bernardino Luini, among Leonardo’s pupils. It was not until 1907 that it would be attributed to Giovan Francesco Caroto by Bernard Berenson, when the first intensive studies of the Caroto brothers began to take off; a certain closeness to the Child holding a toy by Bernardino Luini from Lord Carysford’s English collection (now the Proby Collection at Elton Hall in Peterborough) was also seen. The latter depicts a child in profile against a dark background, chubbier with short, curly hair and a mouth half-open in a smile, but significantly younger in age; however, he addresses the viewer by showing him a toy, which he holds open with both chubby hands.

In the general catalog of Luini’s works, Cristina Quattrini dates this work between about 1527 and 1530, thus to years after Caroto’s Ritratto di Fanciullo . Although the two portraits have as their subject a child smilingly showing something to the viewer, some differences are noticeable: first of all, Caroto has a drawing shown, while Luini has a game of skill formed by two small boards holding a straw; secondly, but more importantly, Luini’s child refers to a conventional model of depiction either of putti or for the figures of the infant Jesus and St. John, while Caroto portrays a real existing little boy. At the time of Caroto’s early studies, however, the Portrait of a Child was displayed in the Museo Civico ’s display in Palazzo Pompei as a derivation “from Luini.” Today it is among the main masterpieces of the Museo di Castelvecchio and has also been chosen as the guide for the major exhibition Caroto e le arti tra Mantegna e Veronese, the first dedicated to the artist, a protagonist of the Veronese Renaissance, at the Palazzo della Gran Guardia in Verona (May 13 to October 2, 2022).

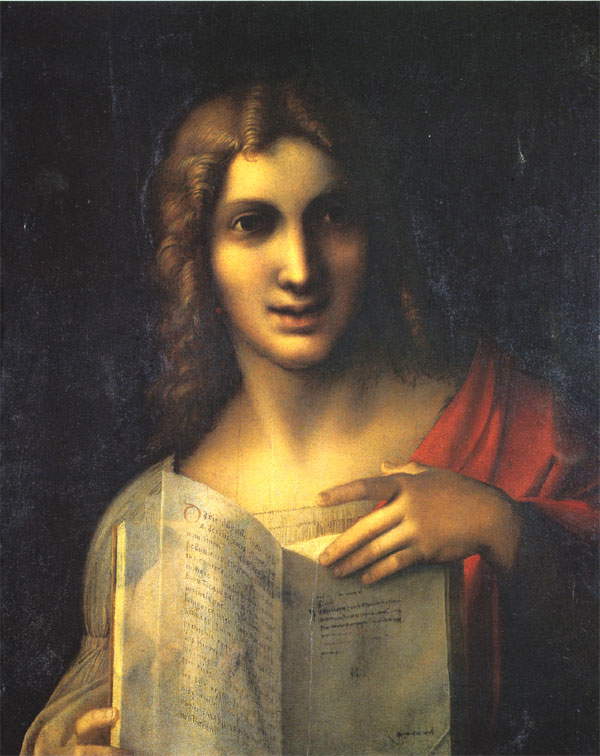

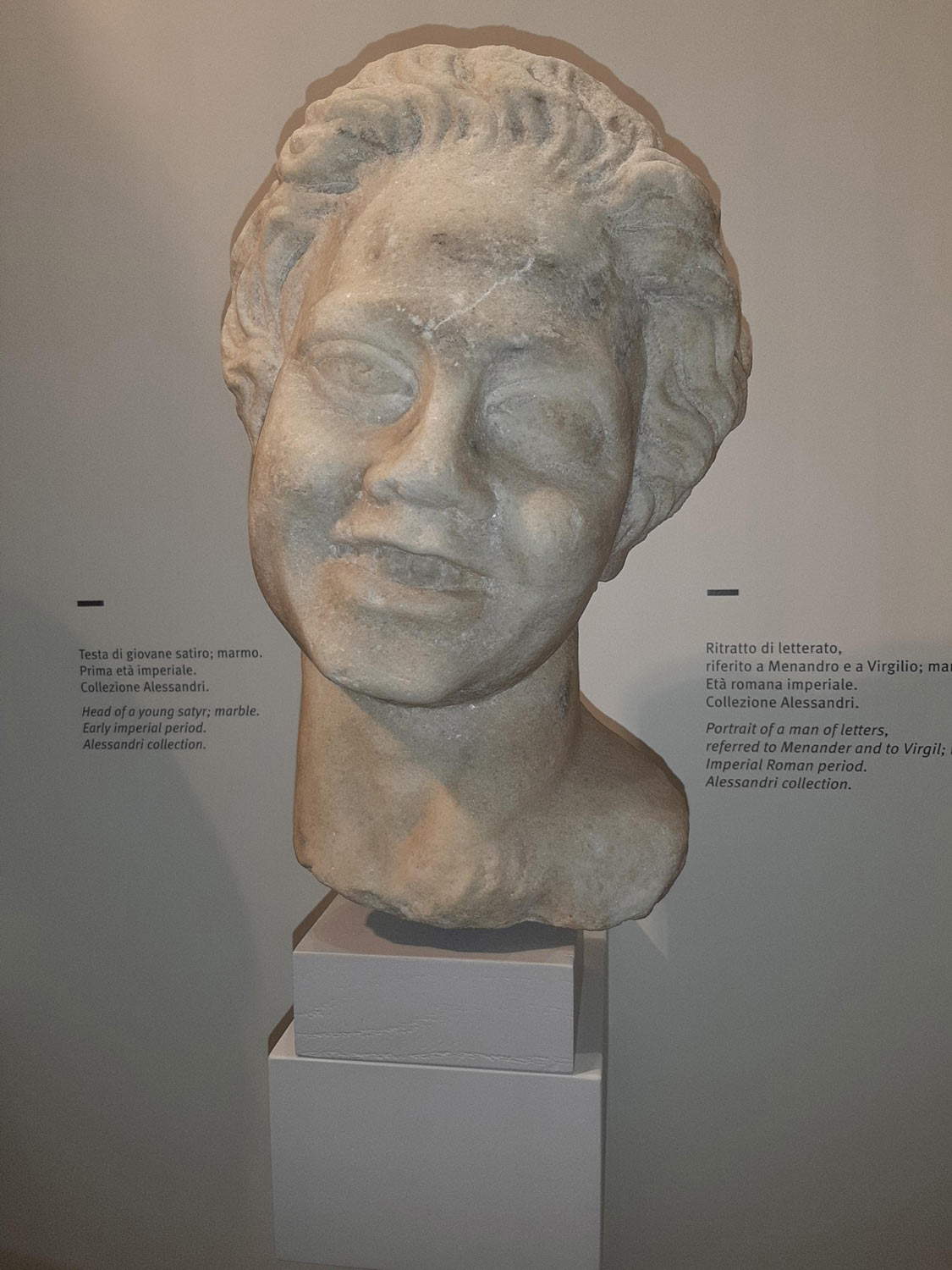

If the style of the painting has been linked first to Correggio (in particular to the Young Christ Showing a Book, datable to 1512 and preserved in a private collection) and then to a Leonardo such as Luini, it is probably because Mantua was fundamental in Caroto’s training, both in Andrea Mantegna ’s last years and in the following years, when in the city, which had very close artistic relations with Verona, the Emilian culture of Lorenzo Costa and Correggio could also be encountered, but the artist was also very much linked to the Milan of the Leonardesque, where he stayed for a long time in the service of Antonio Maria Visconti and in the city he certainly got to know the works of Leonardo da Vinci as well. At any rate, the smile in the Portrait of the Child differs both from those of Leonardo’s tradition, which are more cryptic, and from those that are more elusive and restrained, such as the one that characterizes the face of Cangrande della Scala riding his horse in the Castelvecchio Museum. As models he may have known ancient sculptures that aroused interest in sixteenth-century artists, scholars, and collectors in Verona as evidence of the Roman city: possible examples include the Laughing Satyr in the Archaeological Museum of the Roman Theater in Verona, from the nineteenth-century collection of Carlo Alessandri, and the Pan or Satyr now in Munich (both on display at the Palazzo della Gran Guardia).

Giovan Francesco approached portraiture assiduously and successfully, according to the sources, but his portraiture is still “almost all to be identified and his image as a portrait painter is still rather blurred,” as one of the curators of the Verona exhibition, Gianni Peretti, writes, since “he was always ready to absorb like a sponge the novelties with which he came into contact from time to time.” Vasari tells of a challenge between Caroto and a Flemish painter who in Milan had painted “a head of a young man portrayed naturally.” Giovan Francesco stated on that occasion that his “mind was enough to make a better one,” and he set to work portraying “an old and shaven gentleman with a sparrowhawk in his hand.” A choice with which he ate the victory because the Flemish’s was deemed better: it is thought that the Veronese had erred in not choosing a young subject. Among Caroto’s certain portraits are the Portrait of a Gentlewoman of 1508-1510 kept at the Louvre (the certain attribution came in 1985 when the artist’s signature emerged from the dark background following restoration work) and the Portrait of a Young Benedictine Monk of 1520-1525 kept at the Museo di Castelvecchio, both of which are on display in Verona.

According to Vasari’s account in his Lives, Caroto was a man of good culture, enterprising, curious, intelligent, and also quite prone to irony and sarcasm. Through the boy’s laughter, the observer is led to focus his attention on the drawing the little boy has made on the paper: “a proof of virtuosity, of painting within painting,” as curator Francesca Rossi puts it. If one looks closely, one will indeed notice that alongside the drawn human figure, there appears an anatomical study of an eye in profile made by an expert hand that reveals knowledge of Leonardo’s studies on optics and the human figure. The child then made his drawing on a sheet of paper that had already been used by a more experienced artist. “A first, sketchy test of painting,” the curator explains, which the child accomplished “perhaps by stealing his master’s pen and a sheet of studies to scribble on it his funny little figure, which smacks of an ironic self-portrait in caricature, and now poses amusedly before the painter-and the viewer-without fear of his judgment.”

Caroto was most likely familiar, as a man of culture that he was, with the humanistic researches on pedagogy and childhood by Vittorino da Feltre, Guarino da Verona, Giovanni Dominici, and Erasmus of Rotterdam, which had great fortune in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and along these lines the young man is approached as a pupil who is deeply attached to his master but at the same time overturns all certainties about the rules of art. According to this study by Alessandro Serafini (2015), the painting is “the eternal mockery of the jester, the fool and the adolescent, what every boy has done, does and will continue to do against every preceptor, it is the laughter that subverts all the principles and certainties of the adult world.”

The art world trembled when the Portrait of a Boy with Drawing, along with sixteen other paintings, was stolen in a maxi robbery at the Castelvecchio Museum in November 2015 and found the following year, in May, with all the others. It would have been a great loss: fortunately, a story with a happy ending.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.