The manuscript of the Historiae Alexandri Magni: the dream of the court of Burgundy

The courtly literature that flourished toward the end of the Middle Ages helped to fuel the legend of Alexander the Great (Pella 356 B.C.E. - Babylon, 323 B.C.E.), whose exploits, read through the filter of literary narratives, took on almost fabulous contours.It was not until the fifteenth century that scholars began to take an interest in the true story of the man who went down in history as one of the greatest conquerors ever. Thus, in the 15th century a work from the Roman imperial age was rediscovered, the Historiae Alexandri Magni by Quintus Curtius Rufus, first translated into Italy in 1438, in Milan. Exactly thirty years later, in 1468, the first French translation appeared instead, by the Portuguese humanist Vasco da Lucena, who produced the work at the request of Isabella of Portugal, wife of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy.

The Roman author’s lacunose writing was supplemented by Vasco da Lucena with texts by Plutarch, Valerius Maximus, Aulus Gellius or Justin, and finished in 1468.Vasco de Lucena’s translation presents Alexander as a model, finally freed from the legendary aura that courtly fables had built around him, and as part of the humanistic movement that developed around the dukes of Burgundy. An important manuscript containing Vasco da Lucena’s translation of the Historiae Alexandri Magni is preserved at the University Library of Genoa: it is illuminated by at least two personalities of Flemish taste and training, was made in the second half of the 15th century (it has been dated to 1470-1475) in a workshop operating in Bruges, and was most likely intended for a personality in the close ducal circle. There are other roughly contemporary copies, preserved one at the Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris, one at the Fondation Martin Bodmer in Coligny, Switzerland, and the other also in Switzerland but at the Geneva Library. The Genoese codex is attested in the city as early as the mid-18th century, and features a noble coat of arms (on paper 18 recto), referable to the Piedmontese Solaro Del Borgo family, inserted at a time after the codex was made. The element certifies that in the past the codex belonged to the family, but it is very difficult at the moment to establish both how it came to the Solaro Del Borgo family and how it reached Genoa (to the Jesuit library, the original nucleus of the University Library).

University Library of Genoa

University Library of Genoa University Library of Genoa

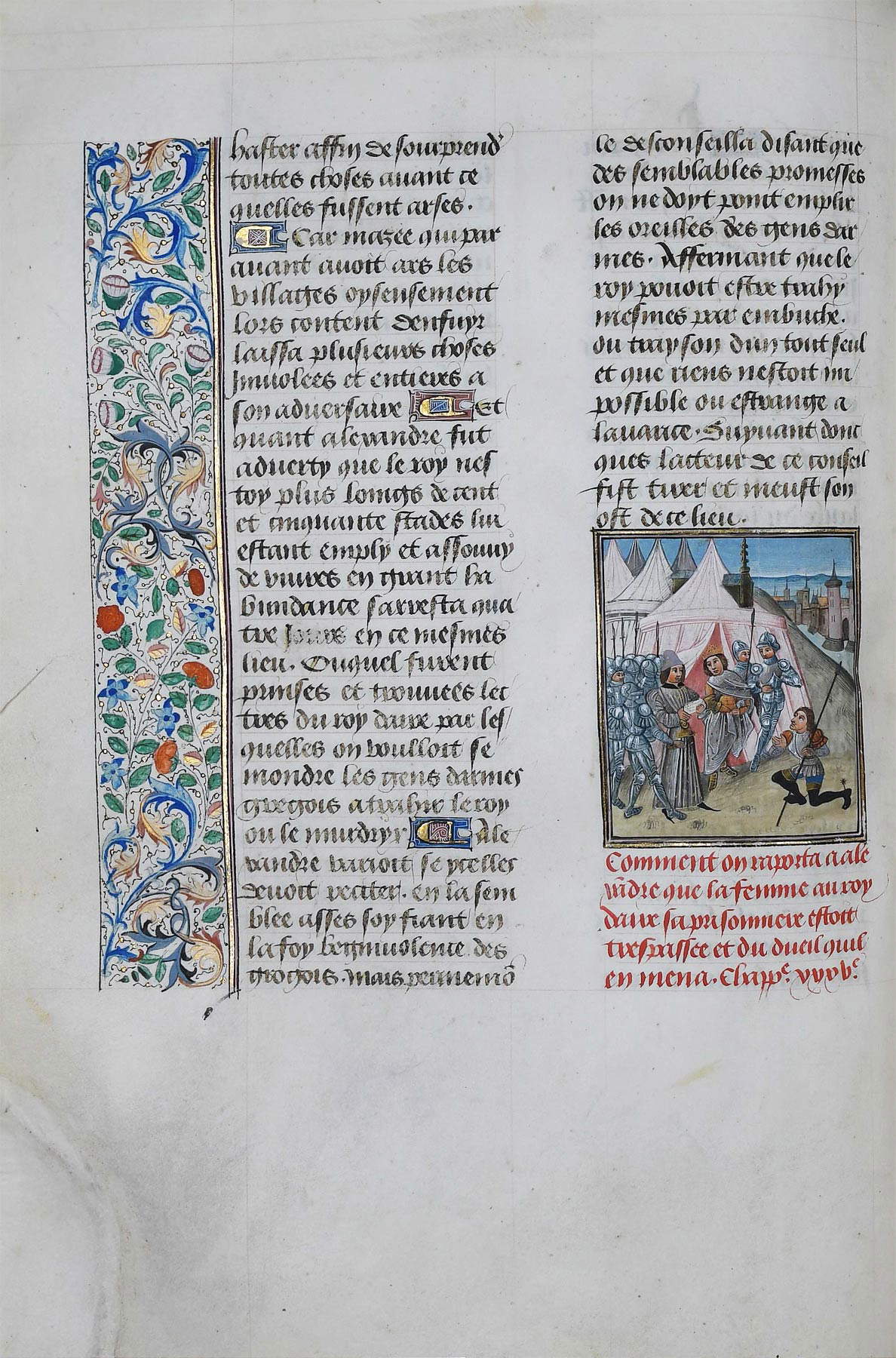

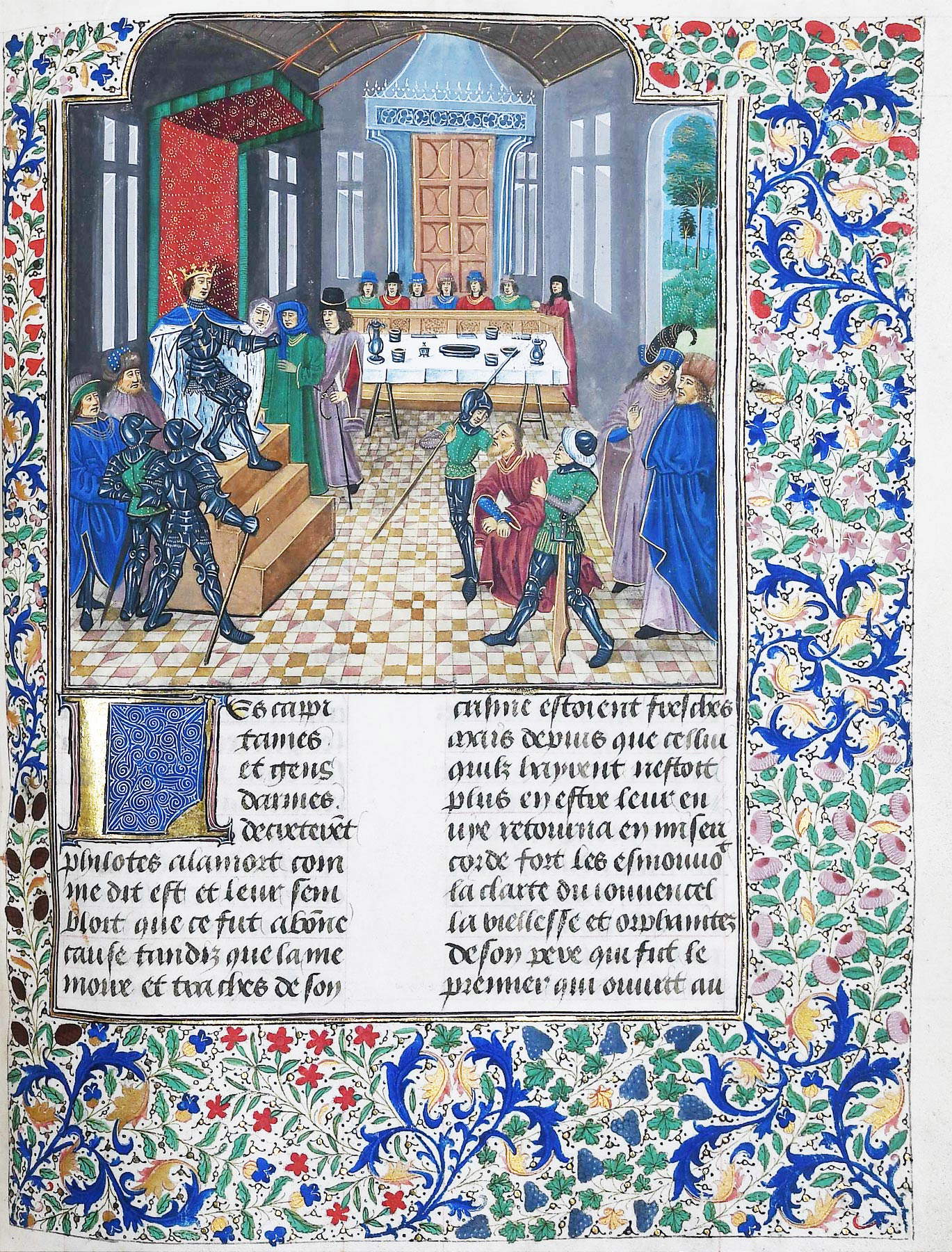

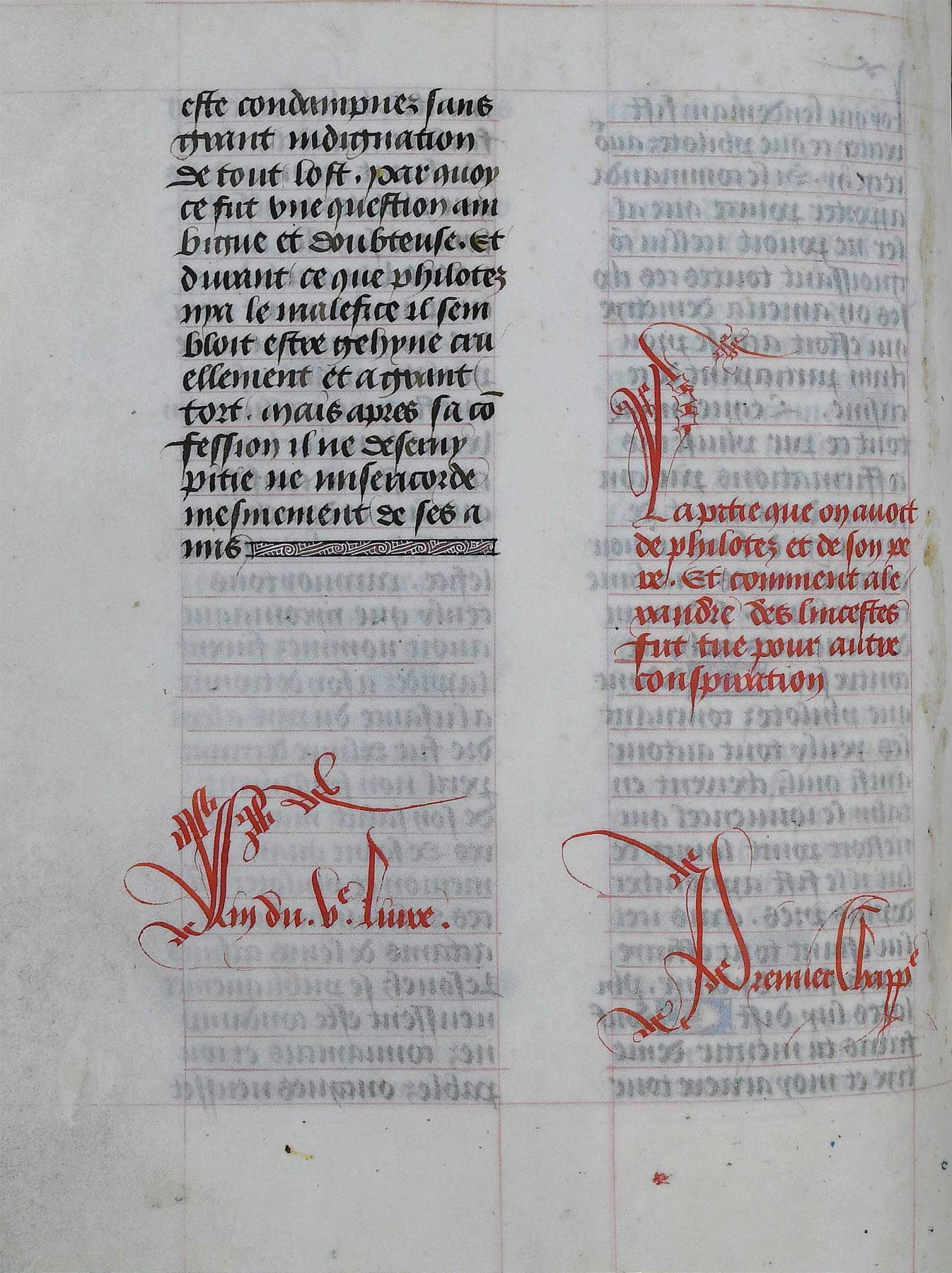

University Library of GenoaThe Burgundian codex preserved in Genoa has not had great fortune among scholars: the first to deal with it was Maria Teresa Lagomarsino in her master’s thesis (in 1958), after which the manuscript was first studied in depth in 1965 by Dino Puncuh, in an essay published in the Atti della Società Ligure di Storia Patria and then republished in 2006. The volume consists of 326 papers measuring 390 by 278 millimeters spread over 42 fascicles, with two guard papers (those inserted between the pages and the cover to protect the former), all gathered in a nineteenth-century red velvet binding with brass studs, which reproduces the antique one. The writing is in two columns of thirty lines each, and traces of the squaring and red-tipped scoring that the copyist had outlined on the sheets to help himself write straight can also be seen. The codex also has eight large miniatures in two columns, each surrounded on three sides by ornamentation with blue acanthus leaves, vine shoots, and green and gold foliage, and another fifty smaller miniatures arranged in a single column. The decoration also includes capilettera i different sizes and friezes in the outer margin on pages featuring the smaller miniatures.

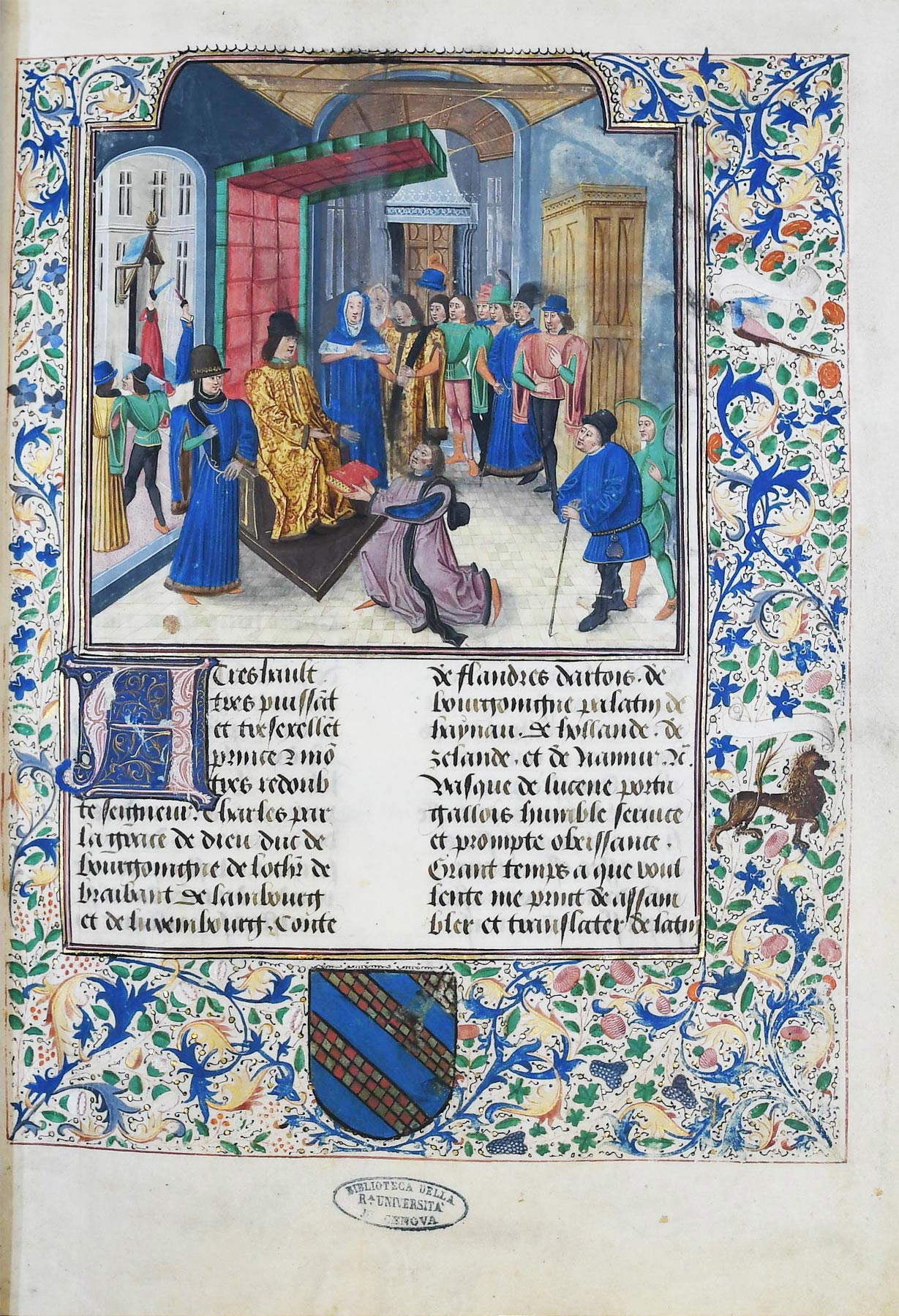

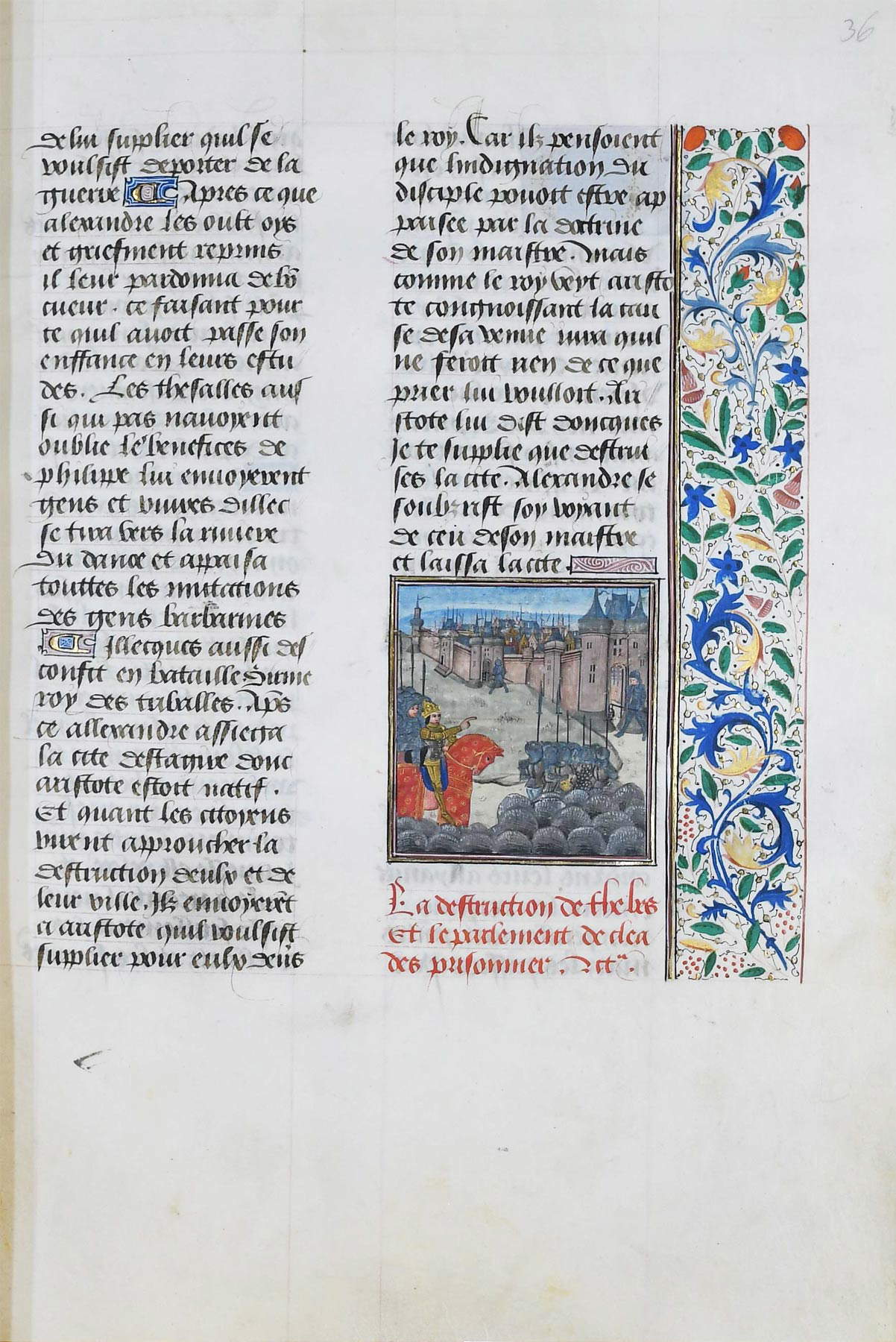

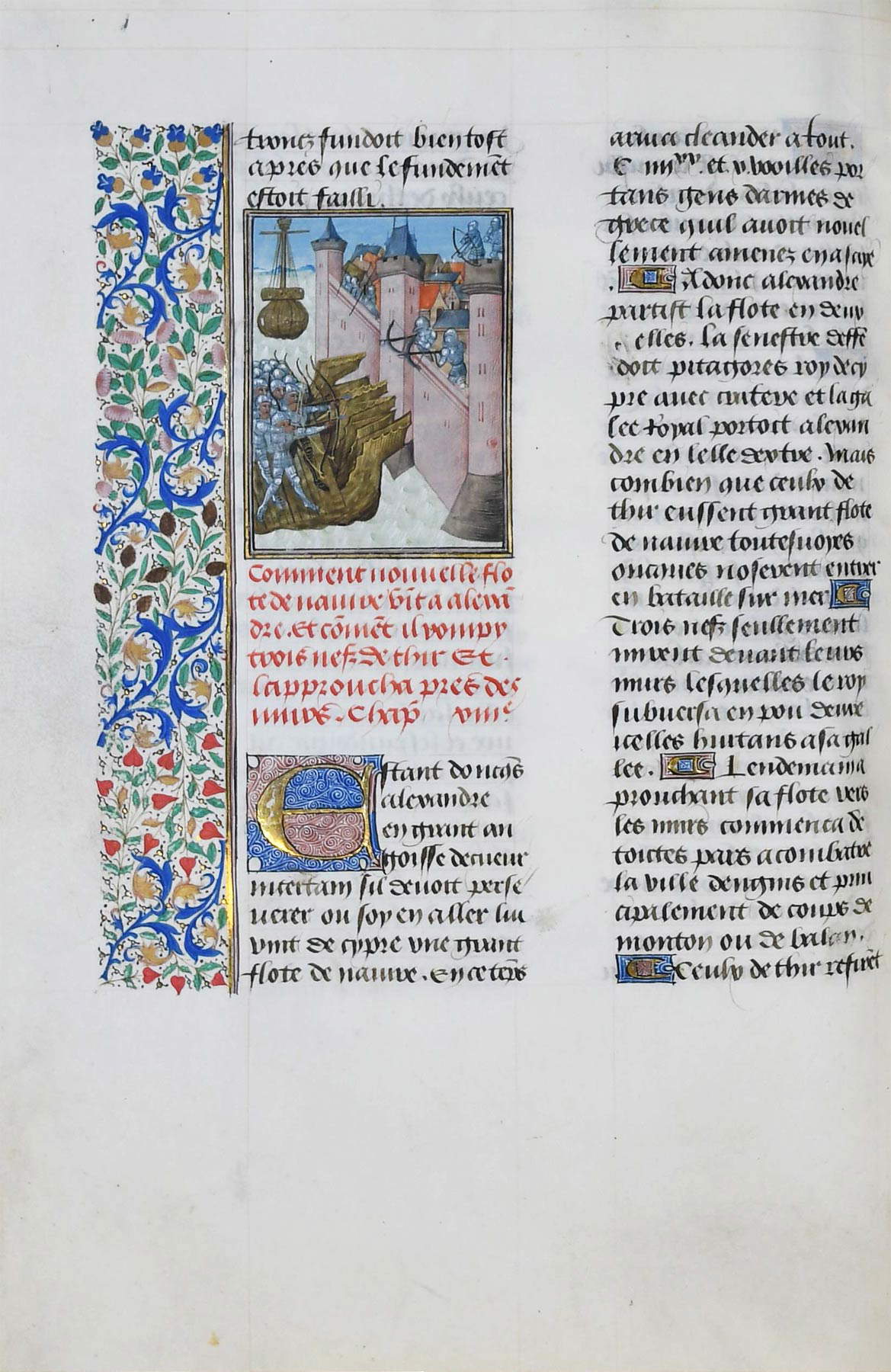

The work, opened by a prologue by the translator, begins with a large miniature depicting the presentation of the volume to Charles the Bold (son of Philip the Good and his successor: he was duke of Burgundy from 1467 to 1477), shown enthroned and surrounded by his court. The treatise is divided into nine books, each richly decorated with miniatures that offer the reader a visual presentation of the events described. The other large miniatures, for example, depict the birth of Alexander the Great, the flight of Darius and his army, Darius’ war council, Philotas being led in chains before Alexander on the throne, Alexander sacrificing to the sun in the presence of his army, and Alexander having some governors of provinces beheaded guilty of embezzlement. A final large miniature is found in the prologue to Book V and depicts Charles the Bold, accompanied by a courtier, on his way to visit the translator intent on his work.

The decorations, according to Puncuh, are due to the milieu of an important Dutch painter and miniaturist, Loyset Liédet (Hesdin, 1420 - Bruges, c. 1478), a specialist in illustrating books with historical characters: characters with rectangular faces and hard, marked strokes, simple landscapes, lots of architecture, and are characterized by very vivid colors recur in his images. “The decisive elements for the attribution of our manuscript to the Hesdin miniaturist,” Puncuh wrote, “are to be sought above all in the sense of color, in the simple landscapes, in the external architectures (with the characteristic central fifth limiting an interior on the left), in the composition of the scenes, and in the appearance and anatomy of the characters depicted. However, the hand would not always appear to be that of the master: if the architectures indeed appear well-defined and conducted with quality, the same cannot be said of the interiors, ”neglected, sloppy, executed certainly by the pupils who worked in his workshop,“ Puncuh speculates. There would also seem to be the presence of another hand, which Puncuh attributes to an unknown ”Master of Grisaille," who would be responsible for the monochrome parts.

University Library of Genoa

University Library of Genoa University Library of Genoa, Ms.

University Library of Genoa, Ms. University Library of Genoa

University Library of GenoaThe codex is written in Burgundian bastard, a type of script attested in Hesdin, an important writing center that was the birthplace of both Loyset Liédet and David Aubert (active between 1458 and 1479), the principal calligrapher of the Burgundian court, as early as the mid-15th century. All the main aspects of the Burgundian bastard in which the Genoa Codex is written are present in the handwriting that spread in Hesdin in these years: letters that are moderately inclined to the right, with pointed drooping stems, rapid hatching, and a very regular and balanced outline, and then features peculiar to some letters. For example, Puncuh explains, "the e has an eyelet consisting of a large comma pointed upward and connected to the first descending stroke by a thin fillet [...]; the shaft of the f and s, perfectly tapered at the bottom, does not descend much below the line; [...] the folding to the right of the ascending rods of h and l is seldom closed looped; not very pronounced are the proboscis-like flutings of h, m, n or the initial arcuate dashes of m and n; the descending rods of p and q, poorly developed and pointed, tend to curve to the left; [....] the final s, as in all bastards, has the typical form of a pointed capital b; the shaft of the t t tends to curve, point upward and elongate; the use of initial v in the guise of b appears somewhat moderate." This was a script that combined the elegance of Gothic writing with the need for rapidity of drafting: the spread of Burgundian bastardy between the seventh and eighth decades of the fifteenth century was such that it was difficult to understand the origin of a codex from one writing center rather than another.

These new graphic forms appeared at a time in the history of the Duchy of Burgundy when an official literature aimed at exalting the ruling family and spreading a strong national consciousness was being formed: the dukes of Burgundy were so closely linked to the writing centers that the dukes themselves probably intervened in the development of the new script, which probably arose as an adaptation of Gothic also by virtue of the revival of medieval themes and motifs that characterized the contents of the codices. The magnificence of the court of first Philip the Good and then Charles the Bold and this restoration of medieval themes had opened, Puncuh writes, “to literature, music, and art an era of splendid flourishing. The court of Burgundy now set out to rival that of France in a grand political dream, so full of modern anticipations and yet so tenaciously suffused with medieval mentality and spirit. It is a unique experience that ends up pursuing an unattainable dream, aimed at repeating themes and customs of a chivalric society, leaning rather toward the past than the future.”

Genoa’s Historiae Alexandri Magni, with their mixture of humanistic knowledge and dreams of a splendid court, are a shining example of the cultural climate in the Duchy of Burgundy shortly before Habsburg rule descended on the state after the demise of Charles the Bold: Charles’s sole heir, Mary of Burgundy, engaged in a war against Louis XI, who aimed to annex the duchy to France. The conflict ended in 1482, with the end of the duchy, which was divided: to France went Burgundy proper, while Maximilian of Habsburg, Mary’s husband, was assigned Flanders, the Low Countries, Luxembourg and Franche-Comté. The Habsburgs would then continue to hold the title of dukes of Burgundy until the eighteenth century. The Historiae Alexandri Magni thus also testify to the end of an era: it will suffice to recall that in the same years in which this codex was being produced, further south, in the Florence of Lorenzo the Magnificent, Puncuh concluded, “alongside the unscrupulous and realistic Medici politics, modern writing was taking its first steps in the footsteps of the humanistic.”

The University Library of Genoa

The Genoa University Library traces its origins to the ancient Library of the Jesuit College: the earliest records known to us of the existence of a library attached to the schools founded by the Genoese Jesuits date back to 1604, while the acquisition by the Jesuits of the area of the convent of San Gerolamo del Roso, sold to the Ignatian fathers by the Balbi family, on which the construction of the College, completed in 1664, began in 1623 (although the schools had already been established in the gradually habitable parts of the building, between 1636 and 1642). The College of Genoa, like all Jesuit colleges, relied on at least two libraries, the “domestic” one, for school use, and the “Libreria,” housed in the so-called “Third Hall,” which still preserves the monumental part of the library collection. The Library was renovated in the 18th century in the Genoese Baroque style, after which, in 1773, with the dissolution of the Society of Jesus, the College was renamed “Public University” and came under the direct control of the Republic of Genoa. The Jesuit library was thus transformed into the “Libreria della Pubblica Università di strada Balbi” where the libraries of the convents and religious corporations that were being suppressed were brought together. In 1785 the librarian Gaspare Luigi Oderico, appointed in 1778, completed what at the present state of knowledge is the oldest library catalog. Since the 18th century, the book collection of the Genoa University Library, enriched over the centuries, has remained linked to the Genoese university.

The holdings of the library’s book collection count on an important collection of manuscripts, preserved in the “Rare and Manuscripts Room,” housed in the left chapel of the church of Saints Jerome and Francis Xavier, built with special furniture in 1935: the collection consists of about 2,000 codices dating mainly from the 16th - 18th centuries. Among the most valuable pieces are the Florentine Missal, composed and illuminated for the church of Santa Reparata in Florence and dating from before 1296; the Liber Iurium Reipublicae Genuensis from the 13th century; and the Historia Alexandri Magni by Curtius Rufus in Vasco de Lucena’s translation. Prominent among the documentary and archival holdings are theEpistolario di Angelico Aprosio (5,550 inventory units); the Autografi fund (with more than 14.000 letters, constituted by the union in the 1930s-1960s of at least three important nuclei of autograph letters from; the Autographs of the Risorgimento (preserved in fourteen boxes, letters and documents relating to Nino Bixio, amounting to about 3,367 inventory units). In addition, there are numerous and steadily increasing correspondence and minor collections.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.