Tucked away among the medieval alleys of Perugia, after a steep climb, is a quiet and little-known place, far from the routes of mass tourism, where it is possible to see two great masters of art history side by side, in comparison, namely Perugino (Pietro Vannucci; Città della Pieve, c. 1450 - Fontignano, 1523) and Raphael (Raffaello Sanzio; Urbino, 1483 - Rome, 1520): It is the Chapel of San Severo. The name will recall to many that of a chapel of almost the same name found in Naples, the Sansevero Chapel: in the Campania capital, the house of worship is named after the family that had it built. In Perugia it is so called because it is located in the vicinity of the church dedicated to St. Severus, which stands in the highest part of the city, not far from Porta Sole. The chapel is a room adjoining the church: it was formerly part of the 15th-century church of San Severo. Then, when the church was rebuilt in the eighteenth century, the chapel was isolated, turning into a compartment next to the church that can be visited today, and today it has been musealized. From the outside, the chapel will appear anonymous: a brick building with a plain façade, as there are many in Perugia, the result of remodeling over centuries of history, because the chapel has existed since the 13th century. The San Severo complex is located in a small square, which opens right on the highest point of Perugia.

The chapel holds, as anticipated, a fresco in which it is possible to see, in direct comparison, two of the greatest personalities of the Renaissance, those of Raphael and Perugino. The pupil and his master. And of the master, the fresco in the chapel of San Severo represents, moreover, the last work created in Perugia. And as for the pupil, the fresco is, on the other hand, the only work, of the many that Raphael made in Perugia, that is still possible to admire in the Umbrian capital: the others, today, are all preserved elsewhere. The importance of the fresco is such that when the fifteenth-century church was demolished in the eighteenth century, it was decided to preserve the painting, which was incorporated into a specially made room, and given a separate entrance from that of the church.

It is necessary to go all the way back to 1505: at that time, Raphael was a young man who had already been noted for his exceptional skills, and from his hometown of Urbino, he had been moving for a year to Florence, a city that offered more job opportunities. Nor was there any shortage of work in Perugia, a city at the time ruled by the Baglioni family, a family as authoritarian and pragmatic in politics as it was refined in artistic tastes and the promotion of artistic talent, and Raphael obtained commissions in both Tuscany and Umbria. And it was precisely in 1505 that he managed to secure a commission through one of the members of the family that ruled the fortunes of Perugia. This was Bishop Troilo Baglioni: it was the bishop himself, as commendatory of the monastery of San Severo (a position he held at the time along with Cardinal Gabriele de’ Gabrielli, bishop of Urbino), who commissioned the painter, then 22 years old, to decorate the small chapel with frescoes.

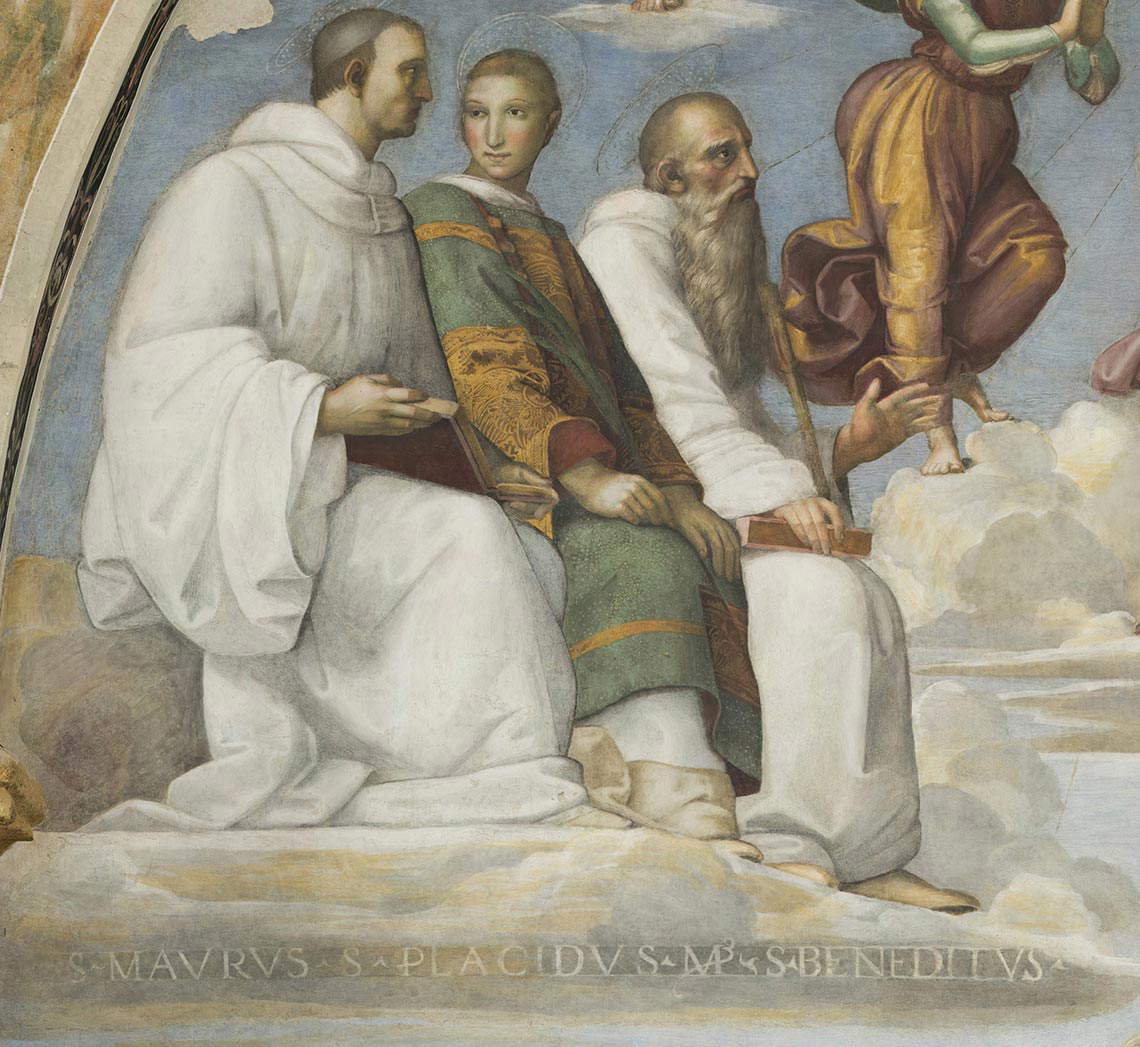

Raphael then received the commission and went to Perugia where he began to paint his work: a Trinity with Saints. However, the artist was overburdened at the time: between 1505 and 1506 he returned briefly to Urbino, a guest of Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, who commissioned some panels, after which he returned to Florence to execute some of his best-known works, such as the portraits of the Doni couple or the Canigiani Holy Family, painted for the Florentine Domenico Canigiani, not to mention the Baglioni Altarpiece, commissioned by Atalanta Baglioni, now in the Galleria Borghese. And when, in 1508, an opportunity arose for Raphael to move to Rome, where he would work for Pope Julius II, the young artist left Tuscany (and Umbria) to move to the Papal States. However, his fresco in the chapel of San Severo remained unfinished: Raphael only had time to paint the figures of the Trinity and those of Saints Maurus, Placidus, Benedict of Norcia, Romuald, Benedict of Benevento, and John the monk, all linked to the order of Camaldolese monks to whom the church of San Severo was entrusted (Romuald was the founder of theorder, Benedict of Norcia the saint whose rule was practiced by the Camaldolese, Mauro and Placidus his main disciples, Benedict of Benevento, also known as Benedict the Martyr, and John the monk were instead two Camaldolese who did missionary work in Poland and were killed by some evildoers who invaded their hermitage).

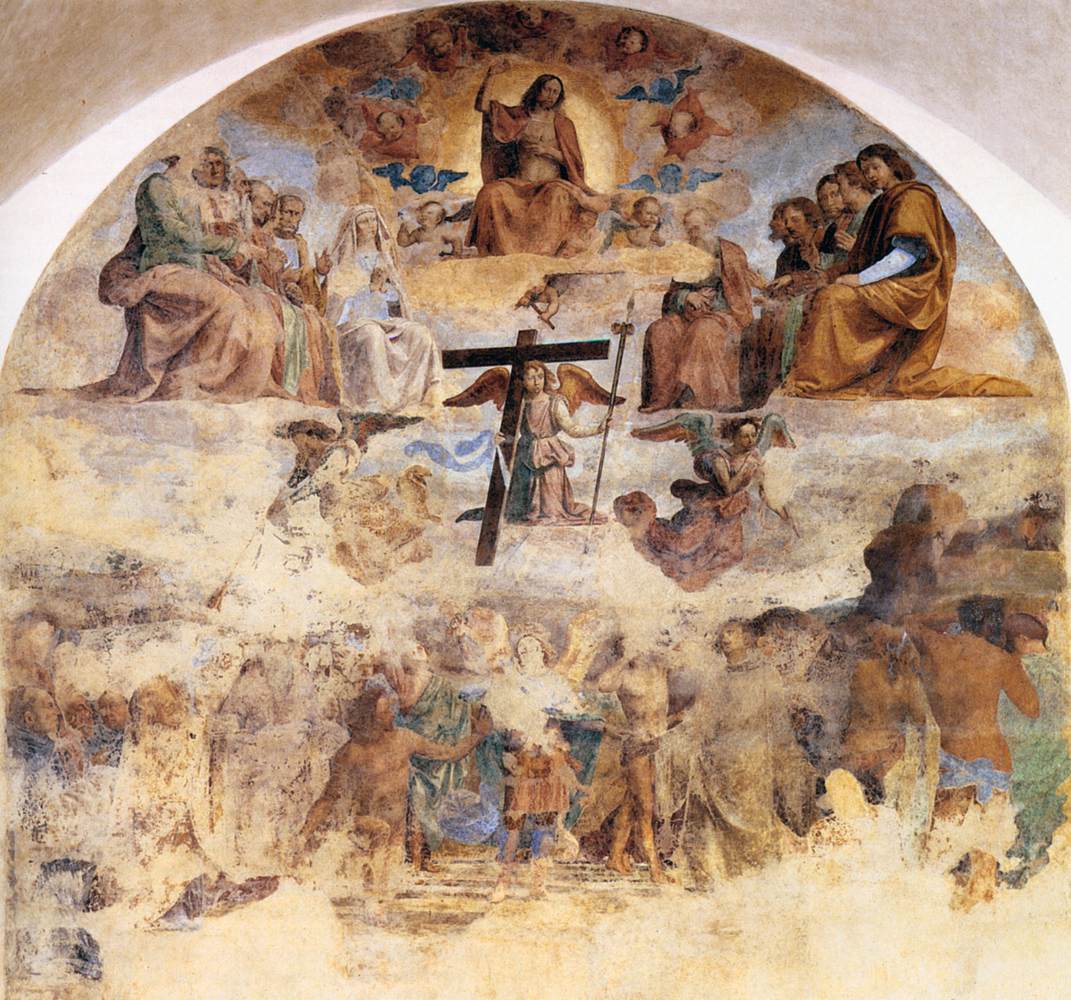

Giorgio Vasari, too, in the chapter of his Lives dedicated to Raphael, describes the work executed by the Urbino: “Et in San Severo of the same city, a small monastery of the Order of Camaldoli, in the chapel of Nostra Donna, he made in fresco a Christ in glory, a God the Father with some Angels in the round, and six Saints seated, that is, three on each band: St. Benedict, St. Romuald, St. Lawrence, St. Jerome, St. Maurus and St. Placidus; et in this work, which for a thing in fresco was then held to be very beautiful, he wrote his name in large and very fine apparent letters.” This is the work of a young Raphael, looking back to the landmarks of his training: in this case the link with the Last Judgment frescoed a few years earlier, between 1499 and 1501, by Fra’ Bartolomeo and Mariotto Albertinelli in a chapel in the cemetery of the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova (now detached and preserved in the Museo Nazionale di San Marco in Florence) is quite evident: identical is the setting with the saints arranged in a semicircle around the main figure (Christ Enthroned in the Perugia fresco and Christ the Judge in that of Fra’ Bartolomeo and Albertinelli), entirely similar are the poses of the characters, similar also is the strongly monumental layout of the composition. It is a scheme that Raphael would later rework in more grandiose and original terms in the Dispute of the Sacrament painted in 1509 in the Stanza della Segnatura in the Vatican.

The Camaldolese probably harbored the hope that the artist would return to Perugia to finish his work, because as long as Raphael was alive, no other painter put his hand to the work. But the fresco remained half-finished for many years. When Raphael in 1520 disappeared, the expectations of the monks having become vain, it was thought to have the work finished by Perugino, who, after a life full of satisfaction and gratification, had for some time returned to live in Umbria. The old painter, who had passed the threshold of seventy years, did not flinch and completed the painting by making the figures of Saints Scholastica, Jerome, John the Evangelist, Gregory the Great, Boniface and Martha. These are the saints in the lower register, arranged around the central niche that houses a terracotta Madonna and Child, attributed to Leonardo del Tasso.

Of the part made by Raphael, some of the figures are no longer legible because of moisture and some restorations carried out in a reckless manner during the 19th century, against which Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle also railed. Thus, today the figure of the Eternal Father is no longer visible (only his huge book with the alpha and omega, symbols of the beginning and the end, remains), the angel to his left, and the figure of St. John the monk, whose legs we see only. The action of time and agents, however, has not been sufficient to obscure the beauty of Raphael’s figures and to allow us to make a comparison, easy, clear and direct, between the young Raphael and his old master.

Raphael’s figures appear moved by a greater vitality, the expressions are deeper, the attitudes more studied. In contrast to Perugino’s figures, which despite their obvious formal elegance, a hallmark of Perugino’s poetics, appear instead more repetitive and similar to figures the artist had already painted in the past. Then there is the difference in depicting three-dimensionality: the stronger chiaroscuro passages of Raphael’s figures make them appear more natural to us than Perugino’s flatter ones. Pietro Vannucci had always been a delicate and refined painter, but in 1521, when he finished the figures of the saints, he appeared to be an artist from another time; his paintings were the product of a genius that belonged to another era.

In those years, the main innovations were coming from artists such as Michelangelo, Andrea del Sarto, and, to broaden our gaze to the rest of Italy, such as Titian or Sebastiano del Piombo, and they had recently left Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, while the first exponents of the period that would be classified by art historians as “Mannerism” were emerging: for it was precisely in 1521 that Rosso Fiorentino fired such a revolutionary painting as the Deposition from Volterra. Perugino thus appears, in this fresco in the San Severo chapel, as a nostalgic artist, an expression of a time gone by.

Art historian Umberto Gnoli, author of a monograph on Perugino published in 1923, made a very harsh judgment on Pietro Vannucci’s figures: referring to Raphael’s figures, Gnoli wrote that “the old master felt nothing, noticed nothing. Not a reminiscence, not a Raphaelesque hint animates that petty theory of saints, old cartoons turned and turned over, the usual ecstatic pose with one foot on the ground and the other somewhat raised, the usual types, the usual folds of the cloaks falling diagonally, a desultory poverty. Perugino, after the Cambio, looked always and only backward at his own art: never around, never ahead.” Softer appears instead Giovanna Sapori, who in her survey of Umbrian works for the volume Pittura murale in Italia. The Quattrocento, published in 1995, writes that “the six figures of saints with which Perugino completed many years later the decoration of the chapel of San Severo (1521) are among the extreme but high quality evidence” of the “masterfully ’economical’ and fast painting” of which Perugino had offered numerous examples. It is curious, moreover, to note that the young Raphael, in 1505, had taken the master himself as a model for his figures, with a technique of execution “approachable to that of Perugino,” Sapori again writes, "in the ways the latter had already experimented in the Cambio cycle by moving from a compact and precious painting (an equivalent of that on panel) to a complex and fast ductus , to a visible chromatic matter with airy and modern effects."

The Perugino of the San Severo chapel, in essence, must be seen as a refined artist still capable of expressing himself at the highest level, but no longer in step with the times. And the new one is represented precisely by Raphael, and by that Christ so Apollonian and majestic at the same time that, despite having been painted a good sixteen years earlier than Perugino’s figures, appears much more current. Two epochs in a single fresco, two protagonists of the Renaissance in direct comparison, in one of the most beautiful and calm corners of Perugia, in the heart of the ancient center, in the Porta Sole district. In a chapel where, for five hundred years, the confrontation between master and pupil has been renewed every day.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.