See Narni through the eyes of travelers and painters of the Grand Tour

The ruins of the Bridge of Augustus that appear unexpected and imposing after traveling through hills thick with woods and forests. The ominous gorges of the Nera that evoke mysteries, legends, magical presences. A village with an almost intact medieval facies , but whose origins date back three millennia. All around lonely abbeys, parishes, fortresses, hills, countryside, cliffs. Strong is the impression that Narni and its landscapes arouse even today to those who travel the Via Flaminia and nearby roads to reach the city, the’ancient Nequinum of the Umbrians, which the Romans later called Narnia, from the ancient name of the Nera (“Nar”), believing the previous place-name to be the bearer of misfortune, since the word nequitia in Latin meant “wickedness.” And imagine what feelings these lands must have inspired in travelers who, between the 18th and 19th centuries, lapped them up to finally arrive at the dream of eternal Rome now close at hand.

Many were, in those days, the travel diaries and guidebooks in which it was possible to find accurate descriptions of Narni and its territory, which soon, from places of passage to the Urbe, became for many unavoidable stops on the Grand Tour. It could even be traced back to the very origins of the expression “Grand Tour.” it is in a 1670 book, The Voyage of Italy, by the English Catholic priest Richard Lassels that the first use of the term is attested, precisely in the preface in which the author lists the benefits of traveling, including the possibility of better understanding what one reads in history books (“no one understands Livy and Caesar, Guicciardini and Monluc better, than he who has taken the Grand Tour of France and the Tour of Italy”). Well, The Voyage of Italy does not fail to linger on Narni, though more for its sinister fame than for its wonders: "so called from the river Nar, it was anciently called Nequinum (evil city), because of its inhabitants, who once, besieged, resolved to kill each other rather than fall alive into the hands of their enemies. They began with their children, sisters, mothers, and wives, and in the end they all fell one after another, leaving the enemies with nothing to triumph over but bare walls and ashes.“ Lassels, however, also mentioned ”just outside the city, tall arches that anciently belonged to an aqueduct": he was referring, probably, to the ’aqueduct of the Formina, located on the outskirts of Narni. Decidedly less macabre, and more attentive to the peculiarities of the city, however, is the description that Thomas Nugent devoted to Narni in his popular guidebook The Grand Tour published in 1749. The Irish scholar pointed to Narni as the next stop after a visit to the Marmore Falls, suggesting that the traveler turn, along the way, his gaze to the Augustus Bridge, and then visit the town, despite the fact that the guidebook also reads that “it is very difficult to walk in this town, because one is obliged to go up and down all the time.” And yet, once one gets used to this obstacle, one will benefit from visiting a city “that stands on fertile ground, abounding in excellent fruits and even some mineral waters”, a city known for its Cathedral, its Fortress, its beautiful fountains, and for being the birthplace of Emperor Nerva and the condottiere Erasmus of Narni, the celebrated Gattamelata of Donatello’s monument.

Before that, however, it was Michel de Montaigne who spoke at length about Narni, in his diary of his travels in Italy, written between 1580 and 1581, but published only in 1774, thus at the height of the Grand Tour era: “Cittadina della Chiesa,” he begins his recollection of his stay on April 20-21, 1581, "set at the summit of a cliff at the foot of which flows the river Nera, Nar in Latin; on one side, it dominates a most pleasant plain where this river curves strangely winding. A very beautiful fountain appears in the square." Montaigne was most likely referring to the fifteenth-century fountain in Piazza Garibaldi, rebuilt in 1527, and distinguished by its bronze bowl adorned with the griffins symbolizing the city (the original bowl is now kept at the local Eroli Museum). The French philosopher also did not fail to appreciate the Cathedral of St. Juvenal, but left out the Augustus Bridge on which much of the eighteenth-century odeporics would focus.

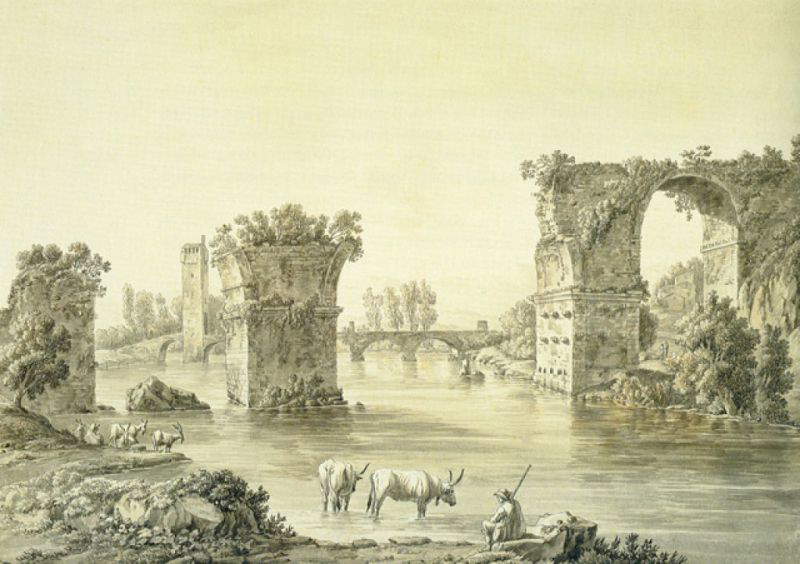

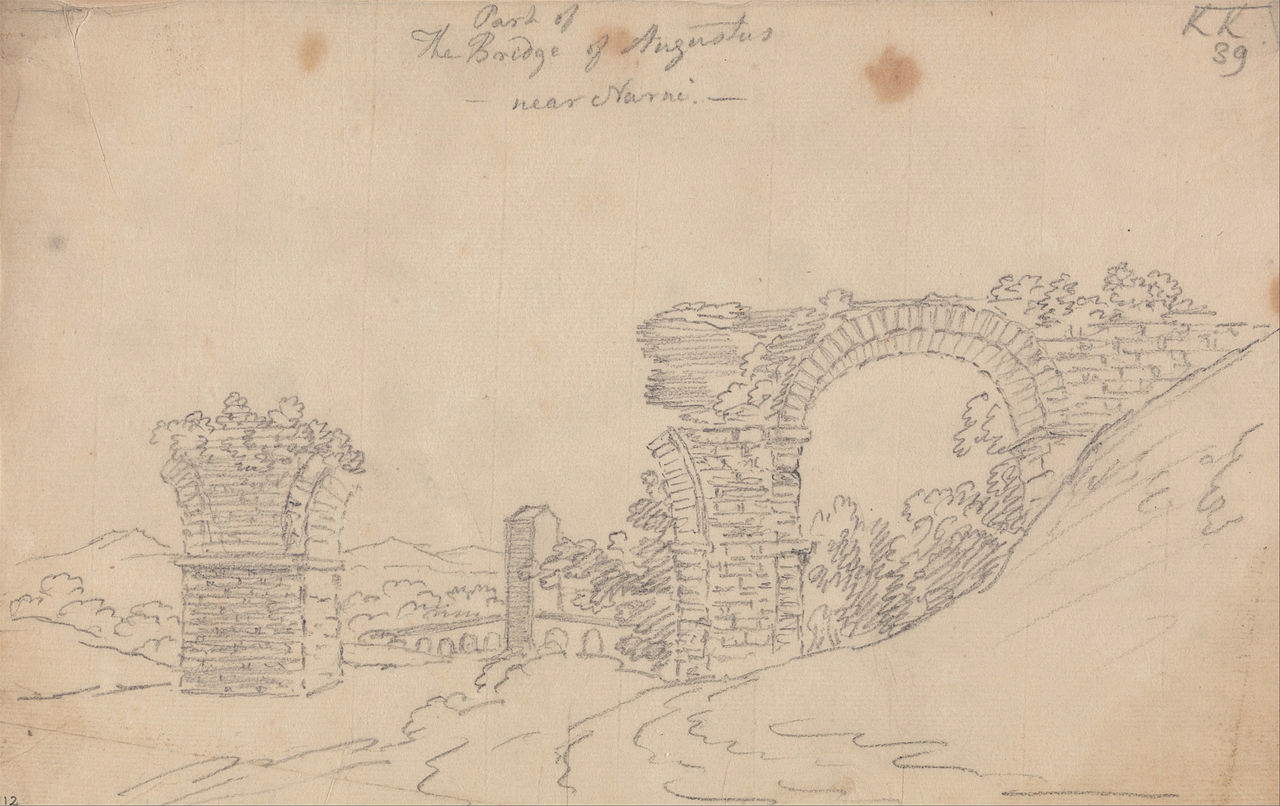

The view of the ruins of the impressive infrastructure was, without a doubt, the one that had most fascinated writers first and painters later. Already Joseph Addison entrusted his memory of the bridge to his Remarks on Italy published in 1705, one of the best-known travel diaries of the time: “I saw nothing extraordinary here,” he said a little disappointed, “except the bridge of Augustus, which is half a mile from the city and is one of the most majestic ruins in Italy. It has no concrete and looks as solid as a whole stone. There is an archway still standing, the widest I have ever seen, although because of its great height it doesn’t look that way. And the middle one was even wider.” The first person to paint the Augustus Bridge was the Englishman Richard Wilson (Penegoes, 1714 - Colomedy, 1782), who had visited the Nera Valley in 1751 on his way down from Venice to Rome: his view of the bridge, now in a private collection, was executed not far from the date of the trip, and according to a fashion prevalent at the time the landscape painted is not the real one, but is rather an idealized image, a whimsy where the ruins of the bridge appear along with remains of buildings not found in that area (one glimpses, for example, the Temple of the Sibyl in Tivoli). The charm of those imposing remains, more than thirty meters high, had bewitched anyone who happened to pass by Narni, and it mattered little if one did not know much about the monument’s history: a structure of the Augustan age, we still do not know exactly when it was built or who its designer was, nor even whether it had three or four arches (only one is left), and its history has been ravaged by various natural disasters, against which the ancient restorations, traces of which have been found on what remains of the ancient bridge on the Via Flaminia, were of little use. An earthquake in the ninth century and then a flood two hundred years later caused the collapse of much of the structure, which was followed in 1855 by the collapse of the third pier.

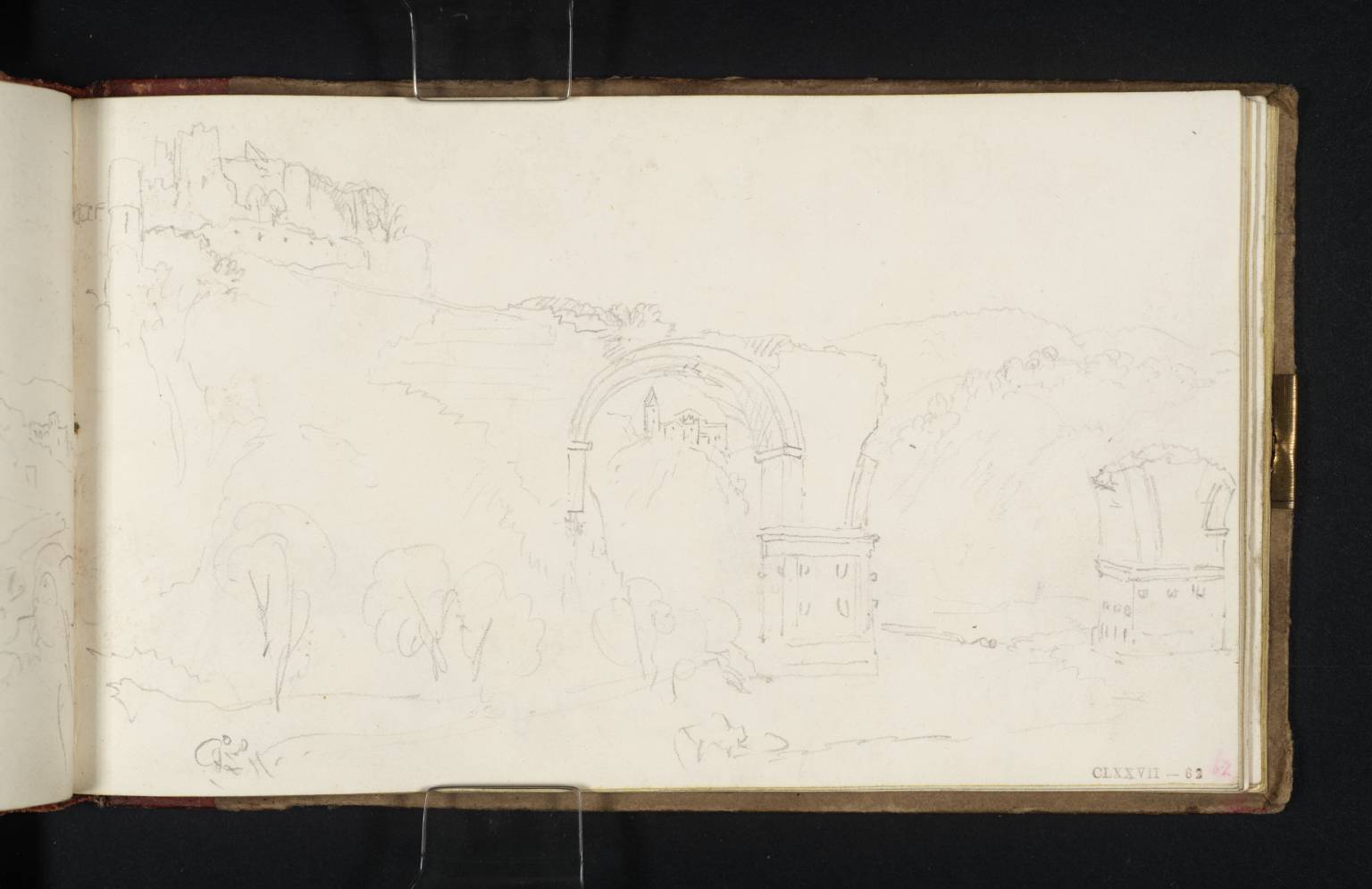

Of the bridge, in short, already at the time when grand tourists were descending on the peninsula from northern Europe, only a few ruins remained, but these must have exerted a strong suggestion, which was able to touch the soul of those who arrived in Italy because they had perhaps read some account or had fantasized about Piranesi’s images, which best conveyed the’idea of the Tempus edax rerum, the time that devours everything, that overwhelms the glories, the honors, the most boundless empires leaving behind only the shadow of what was, and that offer the most immediate image of the “natural forces that take over human work,” as Georg Simmel had written, shifting the balance between nature and spirit in favor of nature, and placing “every ruin in the shadow of melancholy.” This sentiment of ruins connoted Romantic aesthetics and explains why, of the wonders of Narni, it was the Augustus Bridge that was the one most longed for by those who, between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, came down the Nera River to stop at the city of the griffon vulture. “There are few ruins of antiquity,” James Hakewill had after all written in his 1816-1817 A picturesque tour of Italy , “which impress the traveler with greater ideas of the magnificence of ancient Rome than the sight of this bridge.” It was not long before someone was able to provide a true snapshot of the monument: it was in 1776 that the German Jacob Philipp Hackert (Prenzlau, 1737 - Florence, 1807) fixed in one of his drawings the outline of the bridge, traced by turning his back to the city, so that the only surviving archway remains on the right and the medieval bridge further north can also be seen. A dated work, it was executed from life, although you would not know it, given the vivid attention to detail shown by Hackert, and was appreciated to the point that a number of engravings were made from it. Approximately three years later, another English artist, John Robert Cozens (London, 1752 - 1797) sketched the same outline of the bridge arch in a drawing during a long trip to Italy that would lead him to sketch almost every place he visited. Cozens’ drawing is also important because it provided the basis for the greatest of the English Romantics, William Turner (London, 1775 - 1851), who in 1794, the year he executed his watercolor with the Augustus Bridge, had not yet visitedItaly (he would, however, return to our country several times, and had the opportunity to visit the territory of Narni, with the aim of going to the Marmore Falls, between 1819 and 1820, during his first and longest trip to Italy: his notebook preserves drawings of the bridge). One finds oneself, therefore, before an “academic” work, so to speak, executed directly on Cozens’ drawing (Turner’s first supporter, Thomas Monro, had obtained some of his sheets) when Turner was a student who ardently dreamed of our country and, like all young people eager to stay in Italy, did not miss an opportunity to study, to understand, to observe the works of those who had already been to Italy.

A few years later it was the turn of John Warwick Smith (Irthington, 1749 - Middlesex, 1831), who in his watercolor executed around 1781, the probable date of his stay in the Valnerina, captured the bridge by adopting the opposite point of view from that of Hackert and Cozens, and showing himself interested in fitting it precisely into the landscape, without too much yielding to the fascination of the ruin. A fascination to which a great French landscape painter, Jean-Joseph-Xavier Bidauld (Carpentras, 1758 - Montmorency, 1846) seems to have been entirely immune. Or rather: his Augustus Bridge, signed and dated 1790, and passed at auction by Sotheby’s in 2017, sees the ruins of the bridge functional to compose a neoclassical idyll, a landscape depicted on a large scale where what interests the artist is the combination of the remains of’ancient buildings and verdant nature, all bathed in the full, clear Italian light, and complete with a bucolic insertion of shepherds in the foreground to give the sense of a kind of fable inspired by classical literature, according to a taste that was exactly antithetical to that of the Romantic painters. The same is true of the landscape by Pierre-Athanase Chauvin (Paris, 1774 - Rome, 1832) of about 1813, preserved in a private collection: as in all views that respond to the same sentiment, Chauvin’s too, the gaze opens onto the valley and the mountains in the distance, elements caught in the delicate variation of their tones, and as often happens in neoclassical landscapes here too some shepherds inhabit the scene, complete with a flock being led toward the river. We know, moreover, that Chauvin exhibited at the 1827 Salon a painting of the Narni Valley with the ruins of the Augustus Bridge, although the identity of this work is not known with certainty. We do know, however, that in the Salon of the same year, one of the greatest artists of the time, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (Paris, 1796 - 1875) exhibited another view of the Augustus Bridge, now in the National Gallery of Canada, and executed after the study from life that is now in the Louvre. The scheme is still that of the neoclassical landscape, but in the Louvre work, executed en plein air, there is a new immediacy and freshness, discernible in the synthetic approach with which Corot approaches the landscape. The French artist had stayed for a few days in Narni in the summer of 1826, and there were many of his compatriots who stopped in the area. Suffice it to say that Narni was mentioned in one of the most successful travel accounts of the time, Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande’s Voyage d’un françois en Italie, a long account of the stay he made between 1765 and 1766 and published in 1769: Narni is described here as “a small town of three thousand souls, 55 miles from Rome, built in the shape of an amphitheater, on the slope of a pleasant hill, under which flows the Nera,” with passages on the aqueduct and, of course, the Augustus Bridge. Not only that: in 1800, the painter Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, author of a manual of perspective and landscape painting that’had a certain success among the artists of the time, recommended in his book to visit the countryside around Narni and Terni, so much so that two of his disciples (who in turn would become Corot’s masters), namely Achille Etna Michallon and Jean Victor Bertin, followed the advice and visited the area (some of their paintings and drawings of the Augustus Bridge and the Marmore Falls remain). Natural, then, that Corot would also visit Narni, and in this Louvre study the painter returns an image “strikingly powerful in its effects of light and atmospheric transparency as well as in his treatment of the mountains in the background”, wrote art historian Vincent Pomarède, with the foreground elements instead left deliberately undefined because the painter’s intent was to focus on the light reflecting off the bridge piers, the river, and the vegetation. The composition is solid, yet, Pomarède himself noted, something instinctive is discernible: “fundamentally,” the scholar writes, Corot “painted what he saw, and once he had selected his point of view, his concern was above all to work systematically on the contrasts of light and shadow, which become the real subject of this study. Corot executed the painting in the morning, when the penetrating light of the sun comes from the east, that is, from the right side.” The spontaneity of this study, which is small in size but so powerful, even more so than the finished painting preserved in Canada (which is instead much more composed and akin to neoclassical taste), would lead Lionello Venturi to identify this very view of the Augustus Bridge as Corot’s early masterpiece (although there are nonetheless other works from the same period that stand out for the same qualities).

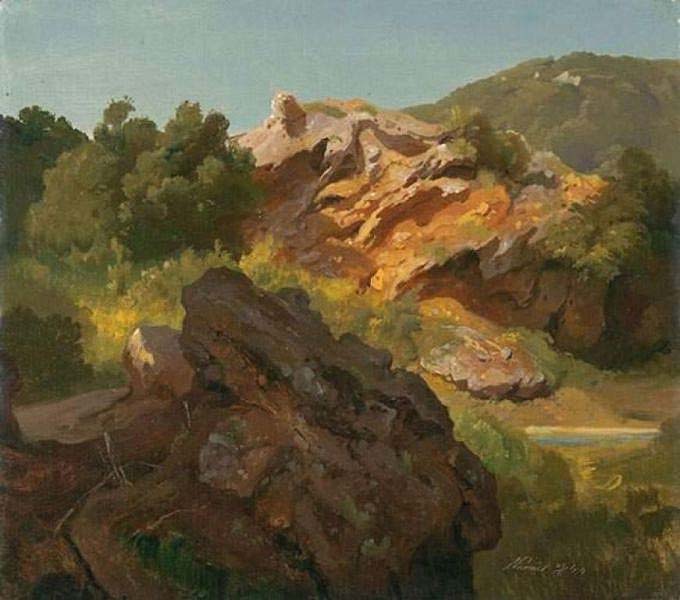

If most of the artists who came to Narni focused on the bridge of Augustus, many carefully observed the countryside, woods and hills near the city, capable of offering magnificent views, unusual and unexpected vistas, an extraordinary variety of views between steep slopes, gorges and overhangs, wide countryside, river landscapes, cultivated land, and intricate and lush forests. Local writer Giovanni Eroli was certainly biased, and he may have been exaggerating when he wrote in the mid-nineteenth century that the Narnese landscape “is as famous for everything as that of Switzerland,” but he cannot be faulted when he praises the enchantment offered by its panoramas, with the view sweeping westward “sublime and majestic” over rocks covered with “a brown and dense forest of ancient elks set among precipitous and sheer cliffs, at the foot of which opens a deep ravine, where the river Nera flows foaming and groaning,” while to the east one can see a “delightful and pleasant valley circumscribed by mountains of various shapes and colors [...], sown with houses, villas, villages, trees, vineyards, and groves.”

Many were the painters who, as Eroli himself acknowledged, were enraptured before the spectacle that nature is able to offer at the gates of Narni. The surnamed Bidauld, in 1787, filmed a cliff in front of the village in a map now in the Carpentras Museum and painted directly from life, en plein air, despite the accuracy of the Occitan artist’s brushstrokes suggesting astudio execution, while the Flemish Martin Verstappen (Antwerp, 1773 - Rome, 1853) allowed himself to be captured rather by the amenity of the Nera valley, as can be seen in one of his paintings preserved at the Galerie du Nord in Lille, France: another view that panders to the taste of collectors of the time for idyllic landscapes, stands out because among the shaded mountains that form the backdrop of the compositional scheme, one notices on the right, slightly illuminated by the sun, the ’abbey of San Cassiano, a 10th-century Benedictine monastery that s’stands solitary on the slopes of Mount Santa Croce, in front of the Nera gorges (it can also be observed from the village’s vantage points, beginning with the recently renovated Terrace of Beata Lucia in the former “Beata Lucia” orphanage in Piazza Galeotto Marzio, which has become one of the sites of the Museo Diffuso dei Plenaristi, which will be discussed at greater length in the conclusion). Instead, the Parisian André Giroux (Paris, 1801 - 1879) focuses only on the river, the author of an exquisite oil on paper that captures a glimpse of the Nera capable of offering the artist the opportunity to study the effects of light on the foliage of the trees, while it is a landscape of rocks that moves theinterest of the German Carl Maria Nicolaus Hummel (Weimar, 1821 - 1907), who in 1844, thus at a time abundantly beyond the end of the Grand Tour as an institution of the European aristocracy, painted several small canvases to account for the harshness of certain views that had accompanied his journey to Narni.

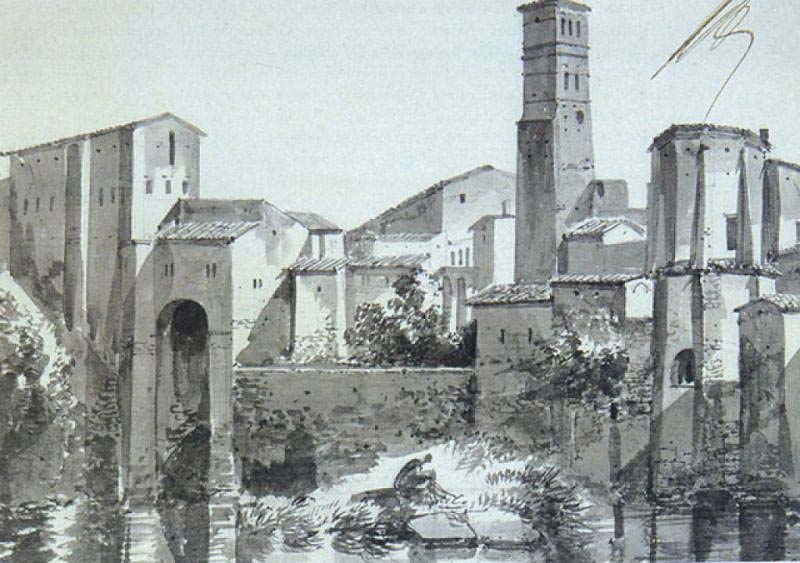

As for the village itself, there are not many paintings depicting it or offering glimpses of its alleys and squares. If we take the era of the Grand Tour as a reference, the works constitute a very sparse group, since the taste of the time favored large open landscapes more than urban views: the first one that can be mentioned is a small painting by Bidauld, kept at the Musée de Picardie in Amiens, where Narni can be seen in the distance, under a deep blue sky, but its buildings are clearly distinguishable (the tower of the Palazzo dei Priori with its wide arches and the mighty squared-off bell tower of the church of San Domenico can be seen very clearly). Then there are a pair of drawings by François-Marius Granet (Aix-en-Provence, 1775 - 1849), both at the Musée Granet in Aix-en-Provence, and dating from the early 19th century: the French artist loved the town’s medieval architecture, so congenial to that glittering idea of the Middle Ages, and particularly the Italian Middle Ages, that had spread in the Romantic era and saw it as a period of purity, splendor and freedom. The proportions are not real, but they tend to interpret the buildings in the village in a geometric sense (take for example the bell tower of the Duomo, which in Granet’s drawing is much more elongated than it really is, while in theother sheet, which appears to be a glimpse of Via del Campanile but we are not sure, it is difficult to find objective topographical matches), and yet suggest with immediate evidence the attraction that the ancient town exerted on the artist.

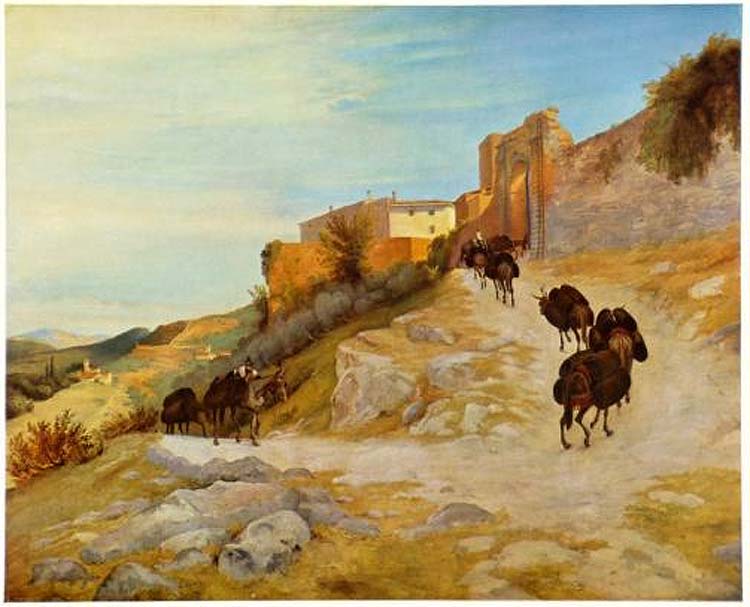

Another artist who focused on the village was the German Karl Blechen (Cottbus, 1798 - Berlin, 1840), who left several drawings in which is traced, in a very dry way (evidently his main interest was to preserve the memory of an impression that he would later deepen in the studio), the profile of the town as seen from outside the walls, all executed from life during the stay of the’artist in 1829, and also some paintings, including a further view of the walls of Narni with a procession of mules advancing toward one of the gates of the town (perhaps Porta Pietra), capable of offering full evidence of the logistical difficulties Nugens spoke of in his guidebook, given that the access roads to the town at that time were indeed impervious and steep. Finally, it will be necessary to wait until the late nineteenth century to see paintings that systematically offer glimpses of the town center. Of particular interest in this regard are the many views of Jacques François Carabain, who traveled frequently through these lands, and throughout Italy in general, in order to paint urban views of the towns he visited (preferably with the inhabitants: Carabain’s was a kind of genuine passion for local folklore), and again a picturesque painting by Michele Cammarano passed at auction by Dorotheum in 2019, in which we see a couple of inhabitants intent on conversing in a courtyard, spied on indiscreetly by a group of villagers, and then we come to the paintings of Giorgio Hinna with which, however, we already trespass into the twentieth century.

One may be disappointed, then, who will look for accurate descriptions of the village in the works of Grand Tour artists. One may, however, resort, again, to literature, rereading the pages of the Marquis de Sade, who had occasion to stop for a long time in Narni and to report of his stay a faithful exposition in his Voyage d’Italie. “Narni,” we read there, “has four thousand inhabitants and is large enough to contain twice as many, but it is depopulated, although the air is good. Above the town there is a castle overlooking it but where the governor does not reside, because of the difficulty of living here, given the altitude. There are a few cops and a prison. In the large hall inside the town hall are two large fresco portraits, one of Gattamelata, captain general of land and sea of the Venetians [...], and the other of Galeotto Marzio, a philosopher: both were from Narni. The fountain in the center of the square called Piazza dei Priori is from 1303 according to the inscription under the basin. The aqueduct that brings water to the city’s three fountains is said to be the work of Emperor Nerva’s father. [...] Entering the city there is a door of Tuscanic order: the door, the two columns supporting the lintel, and the lintel itself are well preserved. One is amazed to see that it faced the rocks. It is likely that the path turned here and rejoined the present path.” There is also no shortage of passages on the history of the city, the Cathedral is described, and a long passage devoted to the Augustus Bridge is read. Hard, in short, to find ancient travelers who passed through these parts without visiting the village. And without being seduced by these places.

Finally, a nod was made more above to the project of the Museo Diffuso dei Pl enaristi (we mean, by the term “plenaristi,” the painters who painted en plein air between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries): a path of knowledge and appreciation of the Terni valley through the painters who painted it in those centuries, begun in 2014. An idea for conscious travelers, modern grand tourists one might say, promoted by the municipalities of Terni and Narni in collaboration with the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Terni e Narni and the Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti a Paesaggio dell’Umbria, and which is articulated in a useful database (where all the paintings of the painters who worked in these lands are catalogued, with rich cards), in two documentaries and in an itinerary on the territory, whose visit can begin precisely from the Beata Lucia, where it is possible to admire, from the terrace, the landscapes so dear to the painters who passed through Narni and its surroundings, where an immersive room has been set up that projects a documentary that takes the public to the Nera Valley of the 18th century with a presentation that alternates images of the real landscape with the works of the artists preserved in museums around the world, and where not infrequently courses in painting from life are also organized. From Beata Lucia then depart the routes to discover the territory, which will be revealed in all its fullness to the eyes of those who have known it through works of art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.