Rome, 1849. The first war reportage in history, by photographer Stefano Lecchi

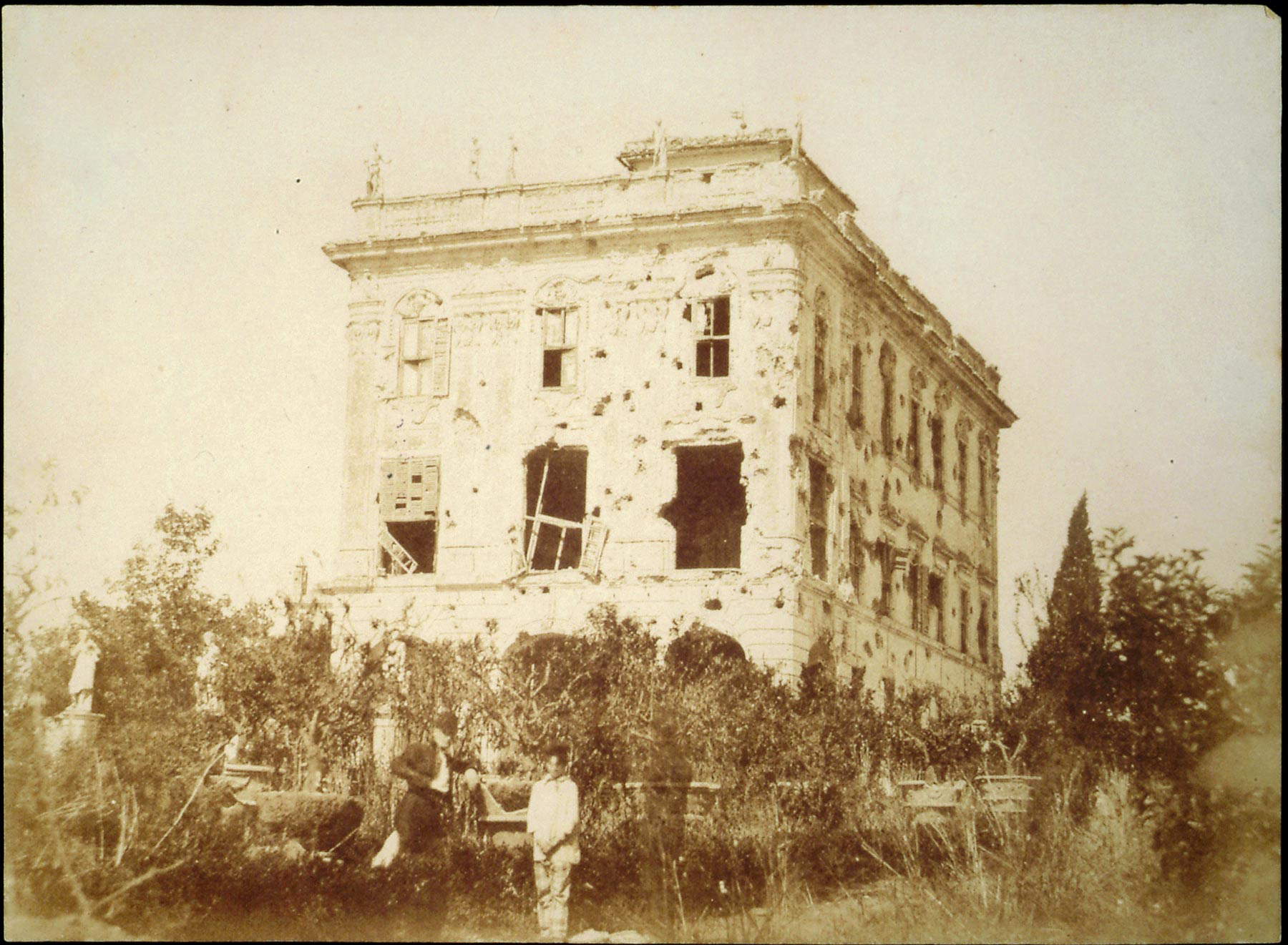

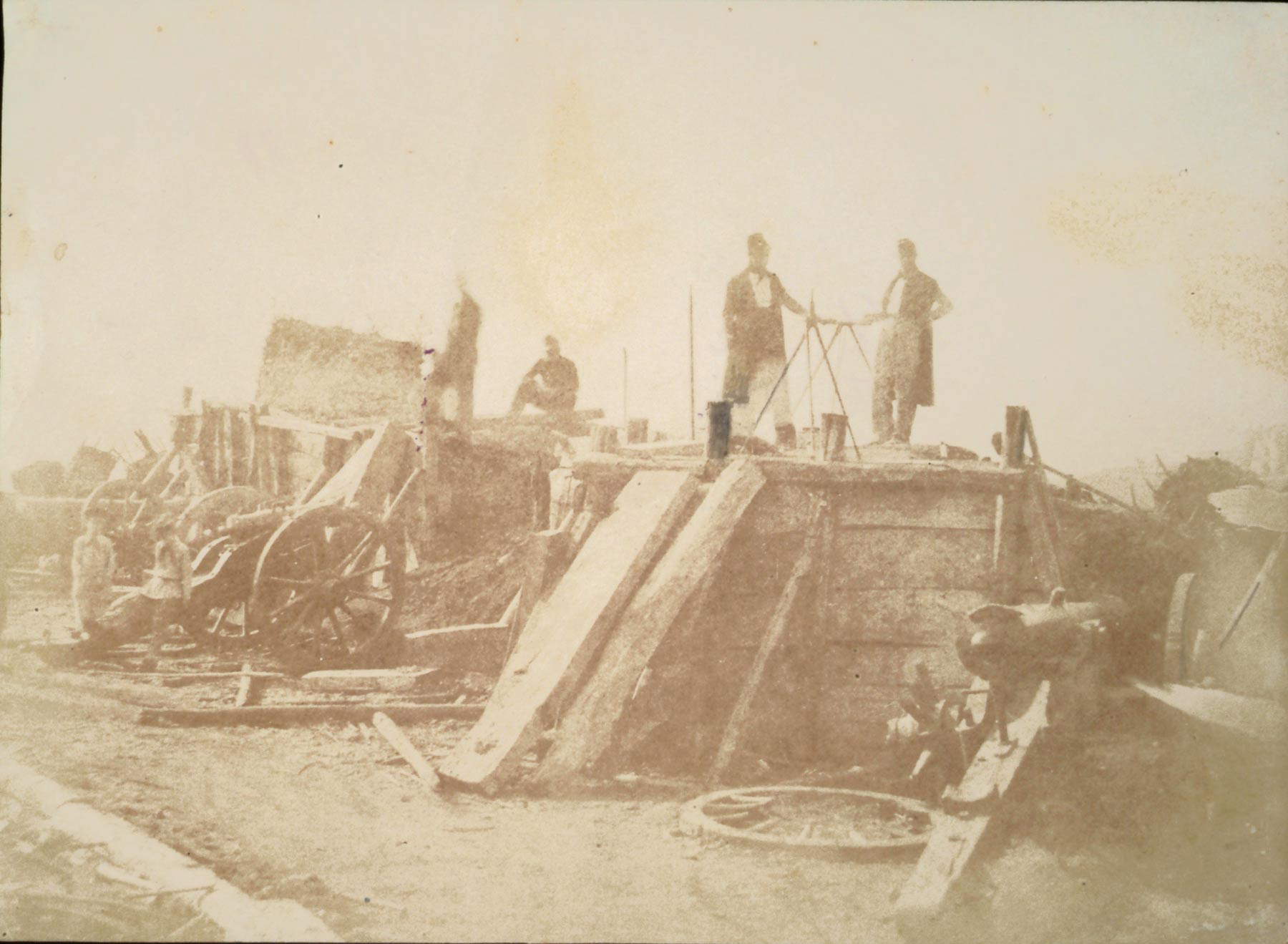

The earliest known war reportage bears the signature of an Italian photographer of whom we have little information, Stefano Lecchi (Milan?, 1803 - post 1866). It is a set of photographs that Lecchi made in 1849 while in Rome: in all, the nucleus, now preserved at the Library of Modern and Contemporary History in Rome, consists of 41 papers salted with iodine bromide. Forty-one photographic prints illustrating as many places in Rome that, between 1848 and 1849, were the scene of the fighting that led to the fall of the Roman Republic, the young state born on Feb. 9, 1849, after the uprisings of 1848 and ended on July 4 of thatyear, following the month-long siege by the French led by Nicolas Charles Victor Oudinot, who had intervened to help Pope Pius IX after his explicit appeal to foreign powers that the pontiff be restored to temporal power.

Lecchi’s photographs are divided into 3 albums, collected in separate passepartouts and stored in a temperature-controlled protected environment. Signed and dated, these images constitute a unique corpus, explains scholar Maria Pia Critelli, “not only because of the technique used, the type and format of the paper adopted (from the Canson company), but also and above all because most of them fix places or buildings related to the defense of the Republic. Two of them, were made in the early months of 1849 and depict buildings, the Casino Cenci and the Casino di Raffaello both located in the Villa Borghese, which will be destroyed for defensive purposes. The other 39, on the other hand, are immediately after the end of the Republic and document the ’new ruins’ of Rome caused by the fighting.”

As mentioned in the opening, we know very little about Stefano Lecchi. Recent research has ascertained that he was probably born in 1803 in Milan, as we learn from the act of his marriage to Anna Maria (or Marianna) Rizzo celebrated in Malta on April 24, 1831, as well as from the birth records of his four children, three born in France (Achille in Paris in about 1838, Mario in Toulon in 1840, Antonia in Marseilles in 1845), while the fourth, Adelaide, in Rome in 1849. Lecchi probably studied in Milan although in the 1930s he was in Paris where he studied with Louis Daguerre. By the mid-1940s he had submitted to the Academy of Sciences, writes scholar Roberto Caccialanza, “an innovative photographic apparatus, different from ordinary ones in that the camera obscura was deprived of the lens, but at the same time equipped with a glass periscope mirror covered with ’amalgamated tinfoil’ that reflected the image on the plate, turning it upside down; it also became possible to operate by adjusting the plate itself and the mirror in order to obtain maximum sharpness and thus focus by acting on an indicator placed on the dial (which showed the measurements of the distances normally used for taking portraits.” His wanderings then took him to various cities in France and Italy to promote the Diorama, a show devised by Daguerre, in the development of which Lecchi himself had collaborated, which made use of some tarpaulins with transparent parts on which some transparent subjects were painted, which were then illuminated to give the audience three-dimensional effects. In 1864 he was instead in Malta, where he was identified on the basis of an address on the back of a photograph of Giuseppe Garibaldi during one of his visits to the island.

Lecchi’s Roman reportage is a recent discovery, dating from 1997. Prior to this date, it was believed that the first photographic reportage of war was that made by Englishman Roger Fenton during the Crimean War in 1855. Then, in 1997, scholar Marcella Miraglia found images of the 1849 defense of Rome, of which only a handful of originals were known: the five in the Siegert Collection, now in the Münchener Stadtmuseum in Munich and the Neue Pinakothek in Munich, while the sixth, depicting the Villa del Vascello (a 17th-century architectural masterpiece designed by history’s first female architect, Plautilla Bricci, and destroyed during the very siege of 1849), was part of the Piero Becchetti Collection. Other images, on the other hand, were known only through a few reproductions, such as those owned by the Museo centrale del Risorgimento in Rome, but it was not suspected to be an organic work.

Then, in 1997, Miraglia found, in the very collections of the Library of Modern and Contemporary History, Stefano Lecchi’s forty-one original salted papers: of these, thirty-nine depict places that were the scene of the fighting, while the other two are, respectively, views of the Casale Cenci and the Casino di Raffaello inside Villa Borghese. Lecchi made his photographic account probably as early as July 1849, shortly after the end of hostilities: the intent is to create, Critelli writes again, a set in which “the image transcends the centrality of the subject represented to become the historical memory of an event fixed not in its occurrence (which was technically impossible at the time) but documented by its traces, ephemeral and destined soon to disappear, that it left behind.” And it was precisely from that date that photography would be used as the main medium for representing wars, even if they were photographs of places that had been the scene of battles: due to the poor sensitivity of the means of the time, rather long shutter speeds were required, as is well known, and this made it impossible to capture battles as they were taking place.

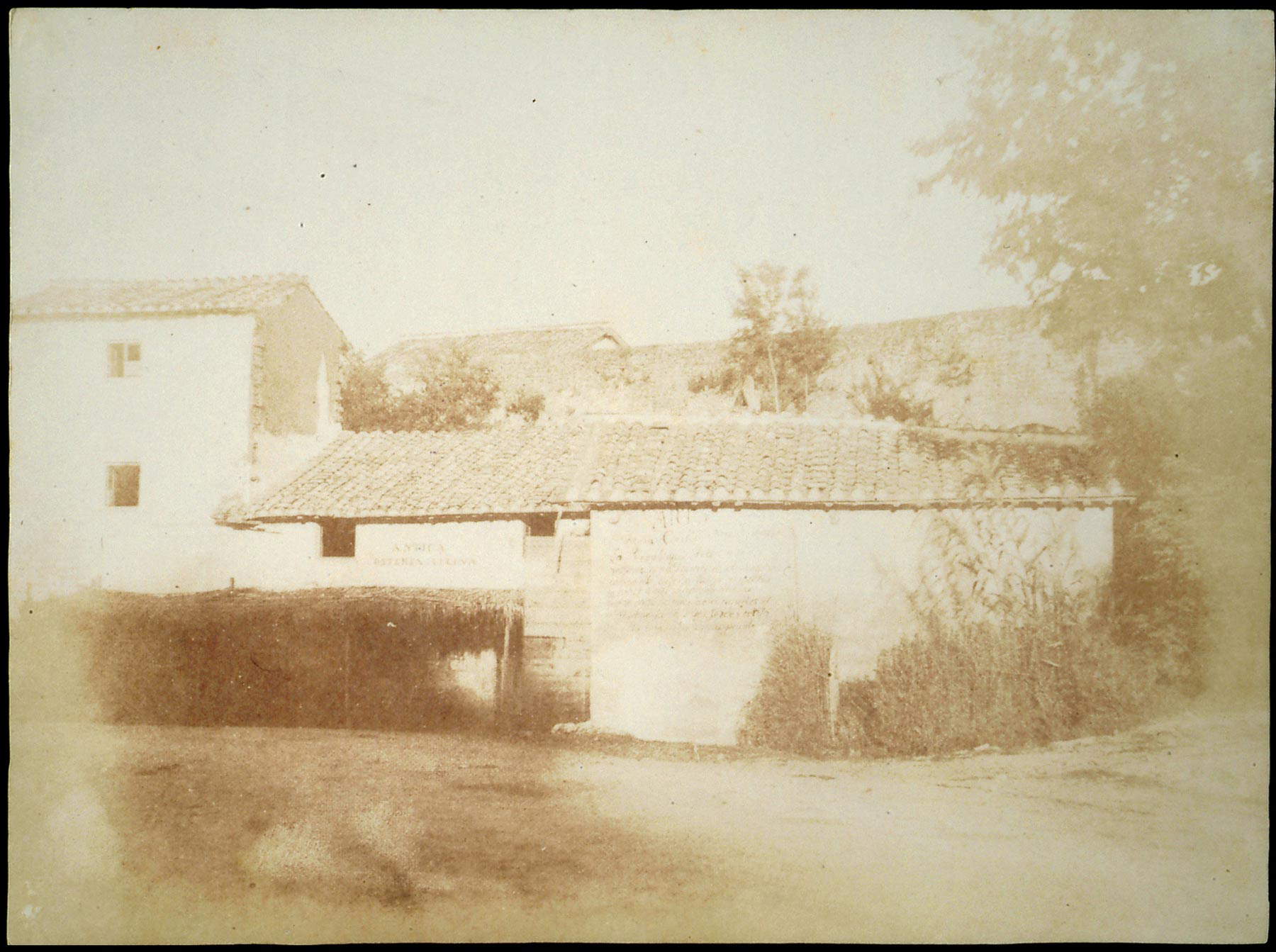

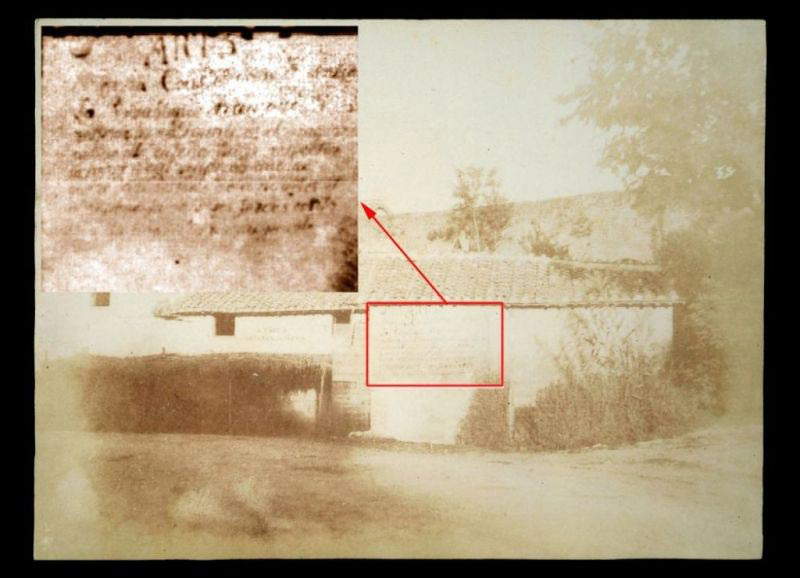

However, we do not know how many photographs were originally taken by Lecchi, nor what motives prompted him to undertake this work, nor whether someone gave him some suggestion about the places to be photographed, or whether there was a commissioner. It cannot be ruled out that the whole thing was the brainchild of Lecchi himself, perhaps driven by a desire to create a visual narrative of what he had witnessed. “The reportage,” Critelli explains, “is not, nor could it be because of the characteristics of the technical means of the time, an exhaustive account of the various moments of the struggle sustained; but it was aimed at recalling them by recording and highlighting their effects. For those who knew and wanted to remember, the places were inextricably linked to individual episodes of battle, valor, facts and the memory of the men who had fought and often died there. Lecchi’s relationship to the traditional way of constructing images is clear in some photographs linked to tradition by an identical code of visual writing. This is especially true when he portrays views of Rome: emblematic is the photograph of the Cenci farmhouse at Villa Borghese, which is almost superimposable, in the setting of the scene, with the analogous image in Landesio and Rosa’s 1842 lithograph. This underscores the incidence, in the formation of his photographic taste, of what was the usual way of reproducing the same place. Well observable in his photographs is the punctilious exactitude in the shots that lead him to photograph certain buildings from different perspectives almost as if the observer could through the images go around it, observe it from different angles, following in the photographer’s footsteps, to the point of identifying himself with his observation and substituting himself for him.” This exactness makes clear Lecchi’s desire to create images that are both a document that organically recounts what had happened in Rome in the early summer of 1849, and also memory and remembrance of those places.

Lecchi’s methods of constructing photographic images are influenced by the tradition of the time: in fact, they present the perspective setting and taste proper to the veduta, a pictorial genre then very much in vogue, and the rare people framed are posed precisely as a consequence of the long exposure times. The Milanese photographer did not lack philological scruple and punctilious attention: indeed, in his images Lecchi shoots many buildings from different perspectives and angles to offer a faithful representation of places, almost mimicking the movements of an observer. Lecchi also paused to photograph buildings that were “minor” because they were related to significant wartime episodes in order to evidently return a thorough understanding of the different moments of the defense of the Roman Republic.

Although we do not have much information on the birth of Lecchi’s reportage, we can get an idea of the way his images spread. The photographs, in particular, did not have great circulation at the time, but on the contrary, their lithographic translations were widely circulated, with some series being derived from his photographs: for example, the plates entitled Ruine di Roma dopo l’assedio del 1849, published by Michele Danesi and Carlo Soleil, and Pompilio De Cuppis’sAtlante generale dell’assedio di Roma , both published in 1849. A thriving market developed for the photographs taken from Lecchi’s pictures, but his name was forgotten: in fact, he appears very rarely in prints taken from the photographs. Even as early as 1849, the print market often used Lecchi’s photographs as the basis for illustrations with large print runs and circulation.

As for the photographs now in the Library of Modern and Contemporary History in Rome, however, they were part of the collection of Alessandro Calandrelli, a deputy to the Roman Constituent Assembly of 1849 and later a colonel in the army of the Republic and triumvirate, together with Livio Mariani and Aurelio Saliceti, after the resignation of the first triumvirate composed of Giuseppe Mazzini, Aurelio Saffi and Carlo Armellini. The items (books, documents, manuscripts) that had belonged to Calandrelli were donated in 1907 by his daughters Elisa and Ludovica to the Vittorio Emanuele II Library: of this collection, the papers concerning 19th-century Italian history became part of the Risorgimento Section, which in the 1930s went on to form the original nucleus of the Modern and Contemporary History Library.

Finally, on anniversary number 170 of the Roman Republic of 1849, the Modern and Contemporary History Library at the address dedicated an online exhibition to Lecchi’s photographs entitled Rome 1849: Stefano Lecchi. The First War Reportage, curated by Maria Pia Critelli and Isabella Poggi, and through which it was made possible to consult images from the collection now owned by the Library of Modern Contemporary History and the Getty Research Institute (Los Angeles). The digitization of Stefano Lecchi’s photographs, curated by Mario Bottoni, was also conducted on the occasion of the exhibition, an operation that made it possible to “modify, in a non-invasive and non-destructive, but dynamic and versatile way, the ’hidden’ or barely legible features of the individual images,” the scholar explains. The result was the detection of details not legible to the naked eye, such as architectural details, people or different objects blended into the landscape, with a significant enrichment of the information conveyed by the images. One detail, for example, made it possible to discover what Lecchi thought of the French intervention. A farmhouse located most likely near Porta Cavalleggeri was digitally enlarged: this enlargement made visible, on the wall of the building, two inscriptions, one reading “ANTICA OSTERIA CUCINA” and the other, far more interesting, showing the fifth article of the Preamble to the French Constitution of November 4, 1848, in the original language, in which the French Republic’s respect for foreign nationalities and the freedom of peoples and its rejection of the war of conquest are proclaimed. This image would later be reused in an 1870 lithograph by Carlo Soleil, with French military personnel included in the scene. Digital processing has thus made it possible to establish that the inscription was not added later by the lithographer but is already present in the original calotype and therefore most likely represents evidence of Lecchi’s condemnation of the French attack.

The Library of Modern and Contemporary History in Rome

The history of the Library of Modern and Contemporary History in Rome originated in June 1880, when the Chamber of Deputies approved Pasquale Villari’s proposal to establish a collection of books, pamphlets and documents on the Italian Risorgimento: thus the Risorgimento Section of the Vittorio Emanuele II National Library in Rome was born. In 1906, the National Committee for the History of the Risorgimento was established with the task of establishing a Risorgimento library and museum, and the Risorgimento Section was entrusted to the Committee. In 1917, the Risorgimento Section took the name “Central Library of the Risorgimento,” assuming the physiognomy of an autonomous library under its own conservator. On the other hand, the final detachment from the National Library with the move to Palazzetto Venezia dates back to 1921, and two years later the new name “Biblioteca museo archivio del Risorgimento” was given.

In the 1930s a number of measures profoundly transformed the physiognomy, and the Risorgimento collection was effectively dismembered: the National Committee for the History of the Risorgimento is suppressed and the museum collection is entrusted to the National Society for the History of the Risorgimento, while the Library is placed under the supervision of a newly established institution, the Italian Historical Institute for Modern and Contemporary Ages, in whose headquarters, at the Vittoriano, the museum and documentary materials end up, except for the autographs of the Mazzini fund, which remain at the library along with the books. The institute took its current name of “ Library of Modern and Contemporary History” in 1937 and in 1939 moved to Palazzo Mattei di Giove, where it is still located today. The Palace was built at the behest of Asdrubale Mattei, Marquis of Jupiter, who entrusted its construction to Carlo Maderno: work began in 1598 and was completed in about twenty years. It has facades of late 16th-century, three-story forms, finished with a cornice adorned with the family’s heraldic motifs, and is crowned by a reredos with a loggia. The palace’s two courtyards and staircase are adorned with sculptures, bas-reliefs and vases, mostly from archaeological excavations on the Mattei family’s estates. A sundial made in the second half of the 18th century by Duke Giuseppe IV Mattei is installed on the floor of the Library’s management office, while the halls of the palace, especially those on the main floor, which house the Center for American Studies, have vaults painted by the most eminent artists active in Rome in the early 17th century, such as Francesco Albani (Biblical Stories), Gaspare Celio, Cristoforo Greppi, Giovanni Lanfranco, and Pietro da Cortona (Stories of Solomon). The paintings that adorned the many rooms and the gallery are now kept at the National Gallery of Ancient Art in Palazzo Barberini.

Finally, in 1945, the Library was placed directly under the Ministry of Education, then, since 1975, became an institute of the then Ministry of Cultural and Environmental Heritage. Until the 1950s, the Library remained linked mainly to Risorgimento studies, while, since the 1960s, it has broadened its field of interest to Italian and European history of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.