Paolo Uccello's Equestrian Monument to Giovanni Acuto, a symbol of the Renaissance

Driving north along the road connecting Cortona to Castiglion Fiorentino, one will notice on the right the Castle of Montecchio Vesponi: until the end of the 14th century, this fortress belonged to the English condottiere John Hawkwood (Sible Hedingham, c. 1320 - Florence, 1394), whose name was Italianized to Giovanni Acuto, and which is most famous today for being painted by Paolo Uccello (Paolo di Dono; Pratovecchio, 1397 - Florence, 1475) in one of the most famous frescoes of the Renaissance, the Equestrian Monument to Giovanni Acuto that is located in the left aisle of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. Giovanni Acuto had occupied in the 1480s the castle of Montecchio Vesponi, which stands solitary atop a hill overlooking the road below, with the approval of the Republic of Florence, for which the mercenary captain would later serve until the end of his days: He in fact disappeared in Florence on March 14, 1394, and was buried with great honors in the city cathedral, although later, following a request by King Richard II of England, the remains were moved to his native Sible Hedingham, a town in Essex not far from London. It was to honor the warrior’s memory that the Republic of Florence commissioned Paolo Uccello to paint the large equestrian portrait, to be placed in the cathedral.

Hawkwood distinguished himself as a young man during the Hundred Years’ War, in the reign of Edward III (although little is known of his military exploits from this period): following the Peace of Brétigny, which marked the end of the first part of the war, Hawkwood moved to France where, in 1362, he founded his own company of fortune (companies of fortune were small private armies that fought for the states that hired them for a fee), the “White Company.” The English condottiero first worked for John II Paleologus, marquis of Monferrato, in his war against Amadeus VI of Savoy, after which, in 1363, he was hired by Pisa (he was in command of the Pisan army defeated by the Florentines in the Battle of Cascina that became famous as the theme that Michelangelo was to fresco in the Palazzo Vecchio in the 16th century), and then by Bernabò Visconti, lord of Milan. In 1372 he fought against Florence for Pope Gregory XI, under whom he remained until 1377: during this period, he was mainly active in the campaigns in Romagna (the tower he had built in 1376 still stands in Cotignola: destroyed by the Germans in 1944, it was later rebuilt in 1972). Once the condotta (the contract made between the captain of fortune, for this reason referred to as a “condottiere,” and the employer) binding him to the pontiff expired, Hawkwood returned to England, except to lend his services again on a few occasions: for example, he was hired by the lords of Padua for whom he fought the Battle of Castagnaro against Verona in 1387, believed to be his greatest victory. Following this event, the English warrior began to fight for the Florentines: he served during the war between Florence and Milan beginning in 1390, conducting a campaign in Lombardy in the spring-summer of 1391 (on this occasion he distinguished himself by a skillful retreat that ensured that the Florentines avoided a clash with the Milanese) and also had some influence in local political events, until his demise in 1394, as mentioned.

History remembers Giovanni Acuto as an often overzealous captain of fortune (as when in 1375, sent by Gregory XI to Città di Castello to suppress a rebellion, he ended up occupying the city, against the wishes of his employer), and as a condottiere who often behaved “like a crazed splinter, which he did regularly when he had no engagement to honor” (so historian Duccio Balestracci, author of an in-depth study of his figure), extremely rigid when it came to collecting fees, gifted with great skills as a strategist but with a career tainted by a few unsavory episodes. His troops on some occasions indulged in rape, unprovoked killings and looting: a little-known episode in the history of Italy (as well as the darkest of Hawkwood’s career), the massacre of the defenseless population of Cesena in 1377 (also known as the “Sack of the Bretons” or “Massacre of the Bretons,” because of the origin of a portion of the soldiers in Hawkwood’s cohort, composed mostly of Breton and English men), when John Acuto’s troops put the city to the sword after a fight broke out between the inhabitants and some of his soldiers, who also would have had no reason to attack Cesena, since it was a papal city and since the White Company at that time worked for the pope. At the time of the events, British soldiers were quartered in Cesena as they were engaged in the siege of nearby rebellious Bologna: to stop the tumult that had broken out after the fight, the papal legate for northern Italy, Robert of Geneva, asked Hawkwood to send reinforcements, which punctually arrived, and despite the inhabitants’ surrender, the British leader’s soldiery subjected the population to continuous violence (there are chilling accounts from theperiod, such as the letter sent by the chancellor of Florence, Coluccio Salutati, to the European sovereigns to denounce what had happened), pillaged as much as possible, and massacred thousands of people (perhaps between 2.500 to 5,000: no old men, women or children were spared, and it was one of the worst massacres in medieval Italy), so much so that, says a Rimini chronicler of the time, “tucte le piaze de Cesena erano piene de omini e femene morte.” Many sources of the time, however, agree in attributing responsibility for the slaughter to Robert of Geneva and in portraying John Acuto as initially hesitant in the face of the papal legate’s orders, and as disinclined to unleash a massacre (according to some, he even saved a thousand women, causing them to flee to Rimini, thus sparing them from a nefarious fate: women who were not killed were extremely likely to be raped).

In Florence, despite his conduct that was often far from exemplary, and despite his behavior with the tax authorities that was at least nonchalant (today we would include him among tax evaders: the documents concerning him abound with objections by the City of Florence and amnesties that demonstrate the Florentines’ favorable treatment of him), Giovanni Acuto was always treated benevolently, so much so that the city thought of honoring him with a monument while he was still alive: as early as 1392, a resolution passed in Florence in which it was decided to build a cenotaph so that the memory of the condottiere would not be lost after his departure, and it prescribed the use of stone, with marble ornaments. Celebrating with a monument a condottiero who had rendered good service to the city was, between the 14th and 15th centuries, common practice. The exceptionality of the measure lay, if anything, in the fact that it was taken with the condottiero still alive.

In any case, the Florentine resolution came with macabre timing because only a few months later Giovanni Acuto died, but the plan to build a sculpted monument did not go through, because at the same time, in 1395, renovation work inside the cathedral also began, and it was resolved for a painted monument, entrusted to Agnolo Gaddi and Giuliano d’Arrigo.

For what reasons was the figure of Giovanni Acuto considered so important that he deserved a monument in the Cathedral? When he passed permanently into the pay of the Florentines in 1387 (he was already receiving a life annuity from Florence, which was granted to him on condition that he did not take up arms against the city), Giovanni Acuto, writes Balestracci, meanwhile represented “the prototype of what was to be the new relationship between a condottiere and his patrons [...], no longer consisting of passing services but of an exclusive and lasting bond between a captain and a state.” Thus, the figure of Hawkwood was perceived as having strong ties to the city of Florence. Moreover, the Republic held in high esteem a commander who had also distinguished himself, however, for his loyalty as well as for the episodes of the 1391 campaign. And again, by the 1530s there had been added propagandistic motives that led Florence to decide to commission the new monument from Paolo Uccello: “the Florentine oligarchy headed by the Medici,” Balestracci goes on to explain, “was beginning to construct the soft transformation of the city’s institutional forms by bending them more and more in the direction already taken after the closures of the 1380s. Within this framework, the figures of the condottieri, Florentines or those who fought for Florence, undergo a resurgence in popularity precisely because they are able to convey the message of the city’s greatness and centuries-old military glory, virtues of which the rising political elite proposes itself as heir, guarantor and continuator.”

So it was in May 1436 that the City Council, recalling the project of forty years earlier, resolved that “the figure of Mr. Giovanni Hauto be remade in the manner and form that lu others wanted painted.” The painted form was again opted for because a marble monument would have cost too much, and the commission was given to Paolo Uccello, who was seen as a painter particularly suited to depicting a man-at-arms (shortly thereafter, the artist would, after all, paint the celebrated Battle of San Romano). It took the artist barely a month to finish the work, which was completed at the end of June: the municipality, however, required the artist to redo it, for reasons that have yet to be clarified. The second equestrian monument to Giovanni Acuto, the one we can still see today, was finally delivered on August 31.

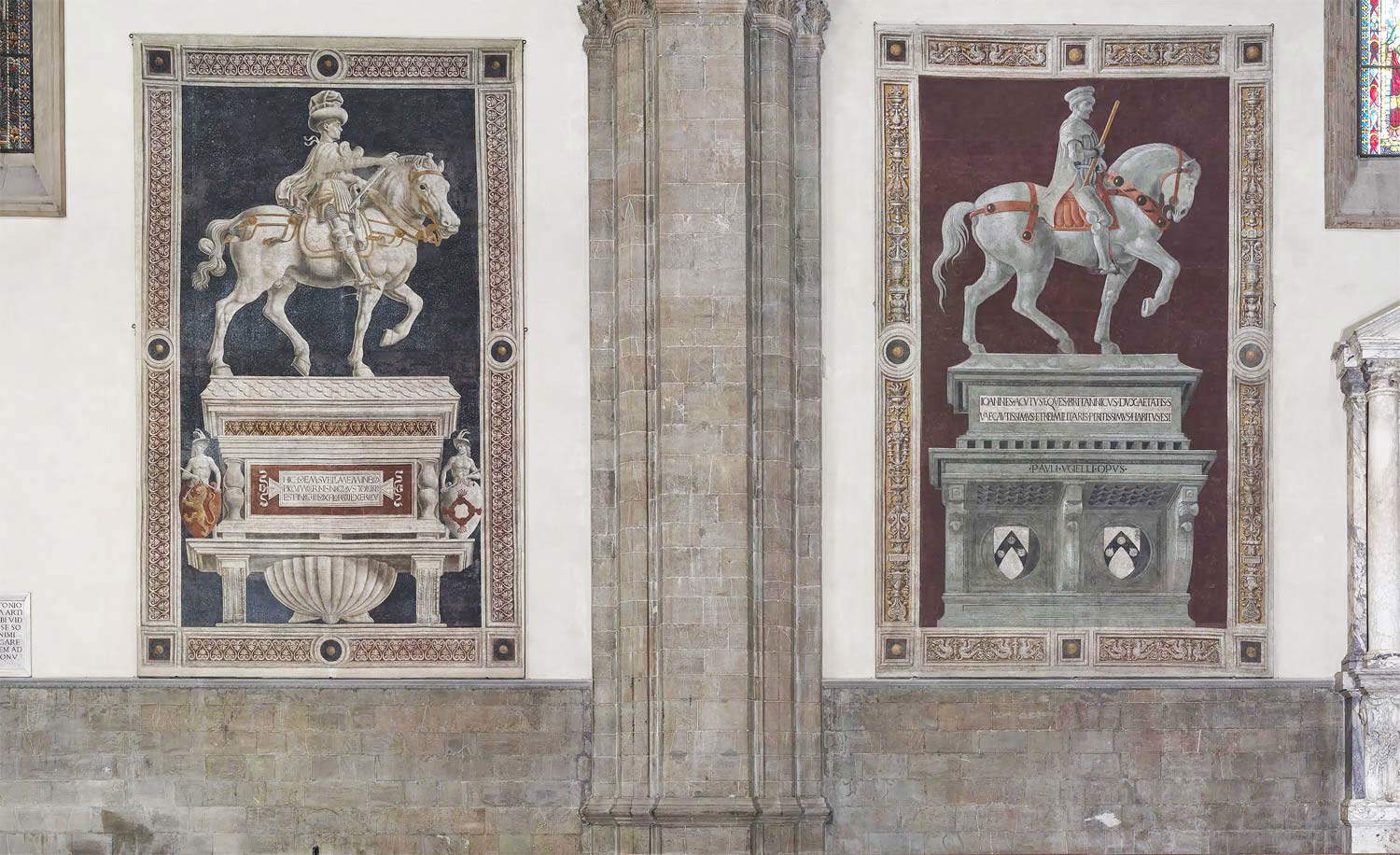

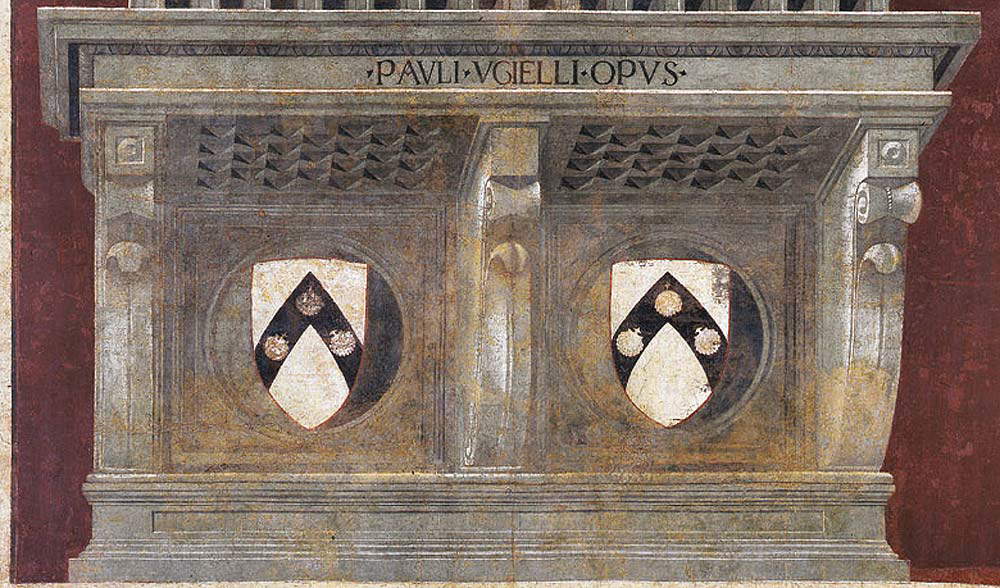

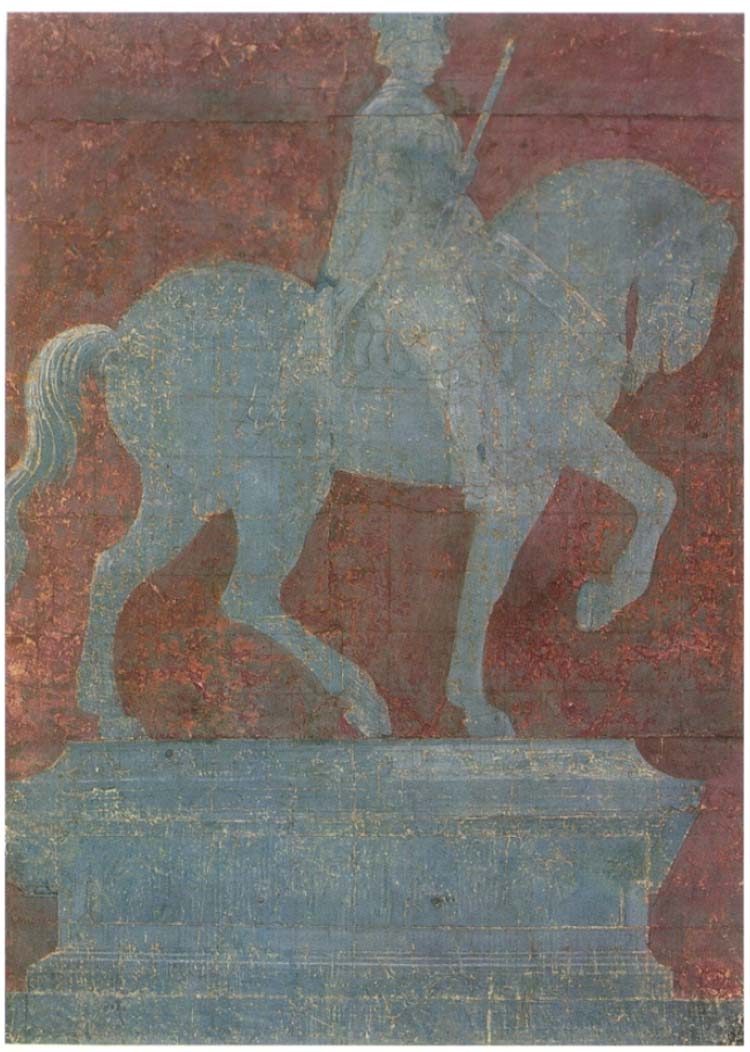

Paolo Uccello depicted Giovanni Acuto in armor, wearing the leader’s cap typical of the time (similar, for example, to that of Piero della Francesca’s Federico da Montefeltro: Paolo Uccello is the first to provide a pictorial representation of it), and wearing a cloak, riding his white horse, in profile, and also painting the figure of the condottiero in a green earth monochrome skillfully declined in striking chiaroscuro to give the viewer the feeling of admiring a marble monument: the only notes of color are given by the red that Paolo Uccello used for Giovanni Acuto’s command staff and for the horse’s light trappings , as well as for the saddle and stirrups. The horse, advancing at the gait of the ’ambio, and thus raising the legs of the right side of the body, with the front one bent, stands above a plinth where it is possible to read the artist’s signature (“Pauli Ugielli Opus,” “work of Paolo Uccello”) and the inscription recalling the qualities of the condottiero: “Ioannes Acutus eques britannicus dux aetatis suae cautissimus et rei militaris peritissimus habitus est” (“Giovanni Acuto, British knight, who was one of the shrewdest commanders of his age and an expert in military affairs”: the inscription was dictated, by resolution of December 17, 1436, by the humanist Bartolomeo di ser Benedetto Fortini). Below, a shelf accommodates, repeated twice, the condottiero’s coat of arms.

One of the special features of this painting, besides the monochrome, lies in the adoption of two different perspective structures: we note in fact that the plinth is strongly foreshortened from below, imagining the point of view of someone who was observing the Equestrian Monument to Giovanni Acuto inside the church, while the figure of the horse and rider are rigidly frontal, most likely because insisting on a low foreshortening would have placed emphasis on the horse’s body and detracted from the figure’s dignity. We should not imagine that the portrait faithfully reproduces Giovanni Acuto’s appearance: in the first place, Paolo Uccello worked more than forty years after the death of the man-at-arms and therefore could not have had any direct knowledge of him, and therefore had to rely on the image painted in 1395 by Agnolo Gaddi and Giuliano d’Arrigo. Moreover, the main problem was not to restore a faithful depiction of the condottiero, so much as to convey an image of his valor: this is why his figure appears abstract, and in some places even geometric (see, for example, the curve described by the horse’s neck, or that of the giornea, or military surcoat, of Giovanni Acuto himself, not to mention the armor’s knee-pad, the perfection of whose circular forms Paolo Uccello exalts).

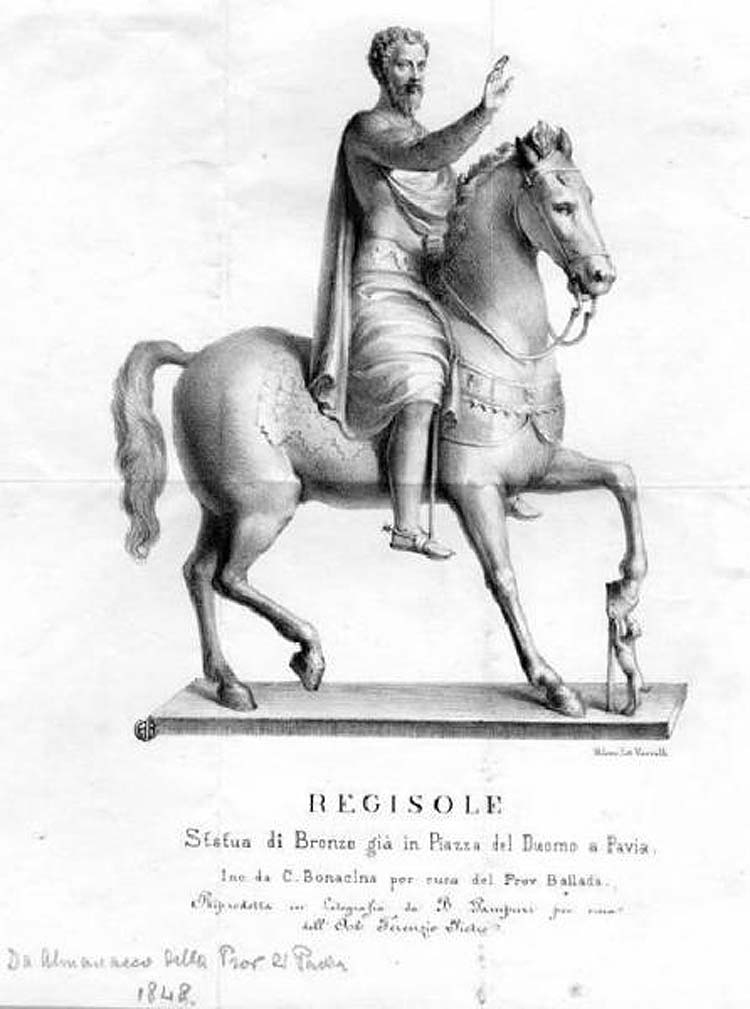

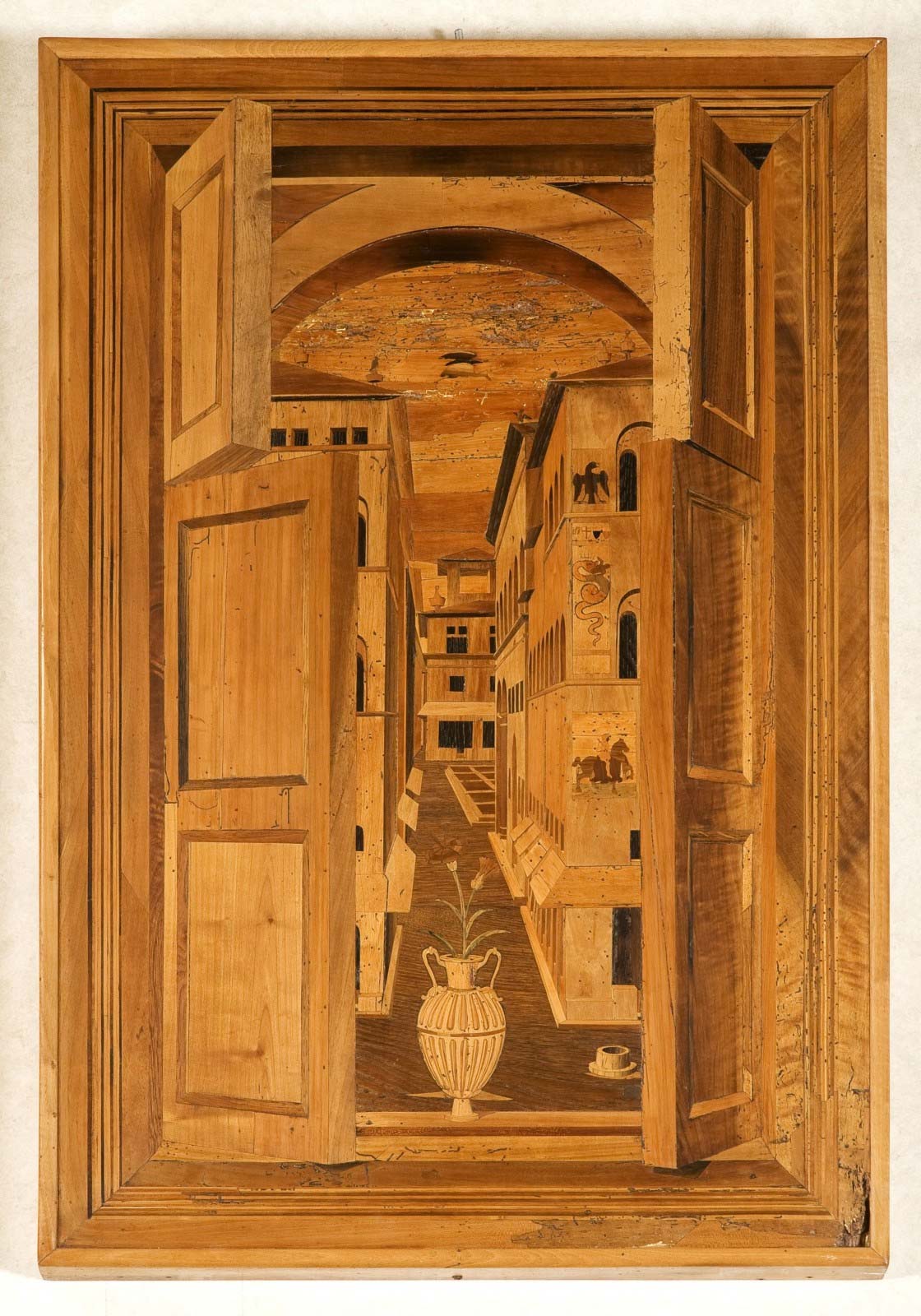

The image that the Florentine painter found himself painting constituted something decidedly innovative for the time. It has been suggested that Paolo Uccello had to look to the very rare models from antiquity, such as the equestrian monument of Marcus Aurelius in Rome, or the lost Regisole in Pavia, or even the horses in the basilica of St. Mark’s in Venice. Certainly, in the capitals of the time, funerary monuments celebrating condottieri who had particularly distinguished themselves abounded, but there were not many equestrian monuments: the monument of Bernabò Visconti executed by Bonino da Campione in 1363 or the equestrian monuments of the lords of Verona on the tops of the Scaliger arches, or, as far as painted images are concerned, the Guidoriccio da Fogliano in the Palazzo Pubblico in Siena comes to mind, thinking not only of condottieri. In the same years, an equestrian monument to Niccolò Piccinino was being painted in Lucca on the facade of what is now Via Pozzotorelli, later destroyed and now known only from a wooden inlay by Ambrogio and Nicolao Pucci, which in ancient times decorated the stalls of the chapel in the Tuscan city’s Palazzo degli Anziani and is now instead preserved at the National Museum of Villa Guinigi. The condottiere Niccolò Piccinino, famous for having been the protagonist (in a negative way) of Leonardo da Vinci’s lost Battle of Anghiari , was an enemy of the Florentines but was instead a figure to whom the people of Lucca were grateful, since the city, under his command, succeeded in repelling the Florentine siege of 1430, and for that feat he deserved a public image. We do not know exactly when the Lucca image dates from, but it is highly likely that it was painted shortly after the 1430 war event: in which case, not only might Paolo Uccello have been inspired by the Lucca work (of which we do not know the’author), but the Municipality of Florence may also have conceived, following a theory expressed by Tiziana Barbavara di Gravellona in her study Sepolcri in honorem, pitture ad infamiam e moente "a maggiore dispetto e vituperio," the equestrian monument to Giovanni Acuto also as a response to the one painted by the rival city in honor of an arch-enemy of Florence.

As for further, possible figurative sources, for the monument to Giovanni Acuto it might be more stringent to compare it not with ancient works (horses of San Marco aside, as will be seen in a moment) or with the Lucca painting, but with the Equestrian Monument to Cortesia Serego, a sculptural work attributed to the Florentine Pietro di Niccolò Lamberti (Florence, c. 1393 - 1435), which is in the church of Sant’Anastasia in Verona: the sculptor, who enlisted the help of stone mason Antonio da Firenze, most likely finished in 1432 the work commissioned by Cortesia II, a descendant of the condottiere depicted, who held the post of captain general of the Scaliger army, and depicted Cortesia Serego in a pose almost identical to that which, a few years later, Paolo Uccello would choose for his Giovanni Acuto. That is, in profile, with the staff of command firmly resting on his thigh, with his cloak along his back, with his horse at the amble (although in the Veronese monument the raised legs are those on the left side of the body), and with entirely similar trappings. Of course, we do not know whether there might be a connection between Niccolò Lamberti’s Cortesia Serego di Pietro and Paolo Uccello’s Giovanni Acuto, nor whether indeed Paolo was familiar with the design of his colleague and fellow citizen (both horsemen appear in anything but unusual poses anyway), but there are similarities between the two images nonetheless. There was then, in the same cathedral in Florence, another equestrian monument, that to the condottiero Piero Farnese, of which we preserve today only the base, in the Museo del Duomo (the equestrian group, lost, is known only from an 18th-century engraving).

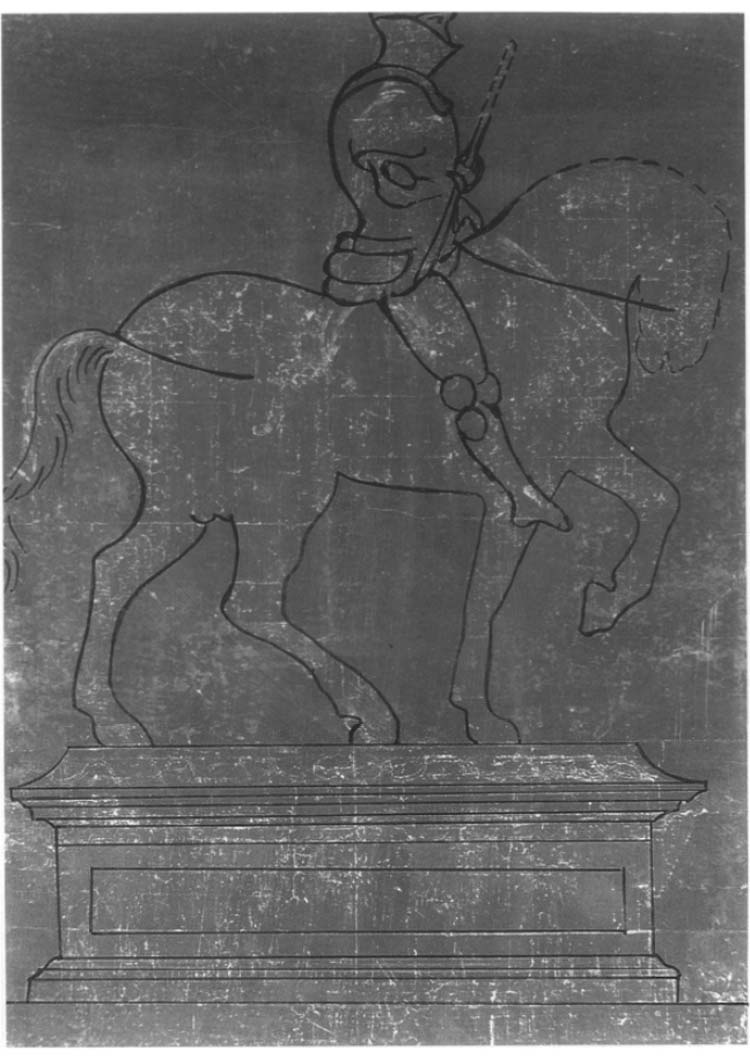

It might be fascinating to ask what the first version of the monument originally looked like, the one that was had redone. This question has been answered by art historian Lorenza Melli by carefully studying the preparatory drawing of the monument kept in the Gabinetto dei Disegni e delle Stampte of the Uffizi: it is a cartoon with the upper part of the monument, and it is believed to be the model for the remake of the first image that the artist presented to the City Council after he was asked to redo the fresco. Diagnostic investigations carried out on the sheet revealed that Paolo Uccello executed it by making numerous changes to an earlier drawing, which analysis revealed had been completed. These would not, therefore, be pentimenti made on an initial sketch: “the underlying drawing,” Melli explained, “was organic and finished in pen details, as on the face of the knight.” Moreover, the cartoon now in the Uffizi is the result of cutting and assembling fragments: for example, the fact that the base is missing altogether was interpreted as an expedient not to retouch a part of the monument that could have been left as it was. From this, in short, it has been inferred that the drawing below the one visible today represents the first version of the design: in this version, John Acute was taller, wore armor complete with helmet, which left only his eyes uncovered (today, however, we see him bare-faced), had metal gloves, wore not the giornea but the armor breastplate, had his leg more extended forward, and the horse had simpler trappings and different dimensions. In particular, Melli noted, the pose of the equine precisely recalled that of the bronze horses of St. Mark’s, which Paolo Uccello had the opportunity to study carefully as, during his stay in Venice, he held the post of mosaicist for the facade of St. Mark’s basilica.

We do not know the reason why the artist was asked to redo the work, although various hypotheses have been formulated: it may be that the equestrian group was too foreshortened from below, or again that the painting did not hold up, or again that it did not meet the taste or, more likely, the expectations of the patrons. What is certain is that with his modifications, Melli wrote again, "the artist [...] brought to the representation a ’civilized’ character and introduced a humanistic tone. Indeed, by replacing the helmet with the capitanesque cap and covering the cuirass with the giornea, he transformed the man-at-arms, who in some ways respected the typology of the Monument to Piero Farnese in the same Florentine cathedral, into a Renaissance condottiere." The Equestrian Monument to Giovanni Acuto is in essence the first “modern” equestrian monument, painted in both form and substance according to the new ideas circulating in 15th-century Florence, and which would later undoubtedly beundoubtedly studied by Andrea del Castagno, for his Equestrian Monument to Niccolò da Tolentino that we see today alongside Paolo Uccello’s painting, as well as by Donatello, when he was asked to design the monument to Gattamelata in Padua.

Paolo Uccello’s work was greatly appreciated by Giorgio Vasari, who described it in his Lives, in the chapter devoted to the Florentine painter, but without sparing a criticism: “He made in Santa Maria del Fiore, for the memory of Giovanni Acuto inglese, captain of the Florentines, who had died in the year 1393, a horse of green earth held beautiful and of extraordinary size, and over that theimage of the same captain in chiaroscuro of green earth color, in a picture ten fathoms high in the middle of a facade of the church, where he drew Paulo in perspective a great chest for the dead, pretending that the body was in it; and above it he placed the image of him armed as a captain, on horseback. Which work was kept and is still a very beautiful thing for painting of that sort; and if Paulo had not made that horse move his legs on one side, which of course horsemen do not do because they fall off (which perhaps happened to him because he was not accustomed to riding, nor practiced with horses as with other animals) it would be this work most perfect because the proportion of that horse, which is very large, is very beautiful.” Vasari, however, did not see the work exactly as we do today: the equestrian monument by Giovanni Acuto, despite its imposing size (it is a fresco eight meters high), has undergone several vicissitudes over time. It was first restored, in 1524, by Lorenzo di Credi, while it dates to 1688 another intervention by Filippo Baldinucci. Then, in 1842, the fresco was transported on canvas by the restorer Giovanni Rizzoli da Cento, following an inspection in which poor conservation conditions were found, with numerous paint losses (the painter Antonio Marini was responsible for the pictorial restoration). On that occasion, the fresco was placed on the counterfacade, where it remained until 1946. Again, in 1947, it was moved again, to where it originally stood, albeit in a slightly lowered position, on the west wall of the cathedral, where we still admire it today.

The history of restoration continued in 1953, when Dino Dini intervened on the fresco because it was always in poor condition: “The reasons that determined a new prompt intervention,” one can read in his report, “were given by certain clearly visible swellings of vast proportions, particularly in the Andrea del Castagno in the upper part of the painting, in the area including the horse’s neck and the knight’s torso, as well as a more minute , but general wrinkling of the painting, and the raising of many small particles of color in the guise of bowl-like crusts,” and this because of the “strong contraction of the canvas according to the thermal variations and humidity of the air, in addition to the action of contrast and behavior of the components of the materials found and used.” This was a complex intervention: it was necessary to remove glazes and remakes left by previous restorations, to fix the support that had had problems after the intel, and to move on to the complete pictorial retouching. Then, in 2000, Daniela Dini ’s intervention to fix the obfuscations caused by dust and atmospheric particulates. Finally, in 2022, again Daniela Dini performed one last intervention, again to solve the same problem: to remove the patinas caused by air pollution. An intervention that was completed in December 2022 and delivered a Giovanni Acuto again free of dust.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.