Judith Beheading Holofernes, the masterpiece by Artemisia Gentileschi

Since the 1670s, the production of Artemisia Gentileschi (Rome, 1593 - Naples, after 1653), daughter of the famous painter Orazio, has always been associated to some extent, particularly with regard to some of her most recurrent, to the feminist cause, not only because she was a leading artist at a time when the painting profession was essentially male (in 1616 she was the first woman to be admitted to theAccademia delle Arti del Disegno in Florence), but also because of her biographical events. Exemplary in this regard is the theme of Judith and Holofernes, of which the celebrated paintings in the Capodimonte Museum in Naples and the Uffizi Galleries in Florence immediately come to mind.

The biographical story has been mentioned because Artemisia was the victim of rape at the age of eighteen yet to be committed by Agostino Tassi (Ponzano Romano, 1580 - Rome, 1644), also a painter and friend as well as collaborator of her father Orazio, and for this reason she often frequented the Gentileschi home. Having fallen in love with the young painter and taking advantage of Orazio’s absence, Tassi broke into Artemisia’s room one day in May 1611: she was painting at her easel when the violence occurred; it is also said that the servant Tuzia did nothing to prevent the rape. Several trials followed the event, and in addition to the interrogations and torture she had to face, Artemisia had to suffer above all the dishonor (both to herself and to her family) that the mentality of the time brought down on the woman victim, as if it were her fault. Only marriage could remedy this dishonor, and initially Tassi promised to marry her; the two dated for a few months until it was discovered that he was in fact already married, causing the promise to lapse. Horace wrote a plea in the spring of 1612 to the papal court denouncing Augustine’s violence toward his daughter. The affair ended with the sentence to be served either with five years of hard labor orexile from Rome: Tassi chose the second option, but he stayed out of the city only until April 1613, when he succeeded in having the sentence overturned. So in fact he remained almost unpunished.

From a feminist perspective, the depiction of heroines such as Judith decapitating Holofernes has been interpreted as a kind of revenge by Artemisia herself (and all women) against Agostino Tassi (and all overbearing men who use forms of violence to bully the fairer sex). In fact, although it is undoubtedly true that the biographical fact influenced at least in part her art and her themes, there has also been a recent desire to emphasize with exhibitions (recall the exhibition Artemisia Gentileschi and her time held at the Museo di Roma in Palazzo Braschi in 2017) how the painter had managed to overcome with moderate speed the vicissitudes related to the violence she had suffered, how well she was included in the courts of the time, but above all how that violence depicted in those paintings that had bolstered autobiographical and feminist theories was actually very recurrent in artists contemporary to her as well, thus demonstrating how these violent and somewhat splatter scenes, as we would say today, were fully within the historical-artistic context in which Artemisia lived and worked. Starting with Caravaggio, the main model for these works by Artemisia, and then moving on to artists such as Valentin de Boulogne, Bartolomeo Mendozzi, Louis Finson, and Giuseppe Vermiglio, as shown in the 2022 exhibition Caravaggio and Artemisia. The Challenge of Judith mounted at Palazzo Barberini and dedicated to the single theme of Judith, developed by direct comparisons.

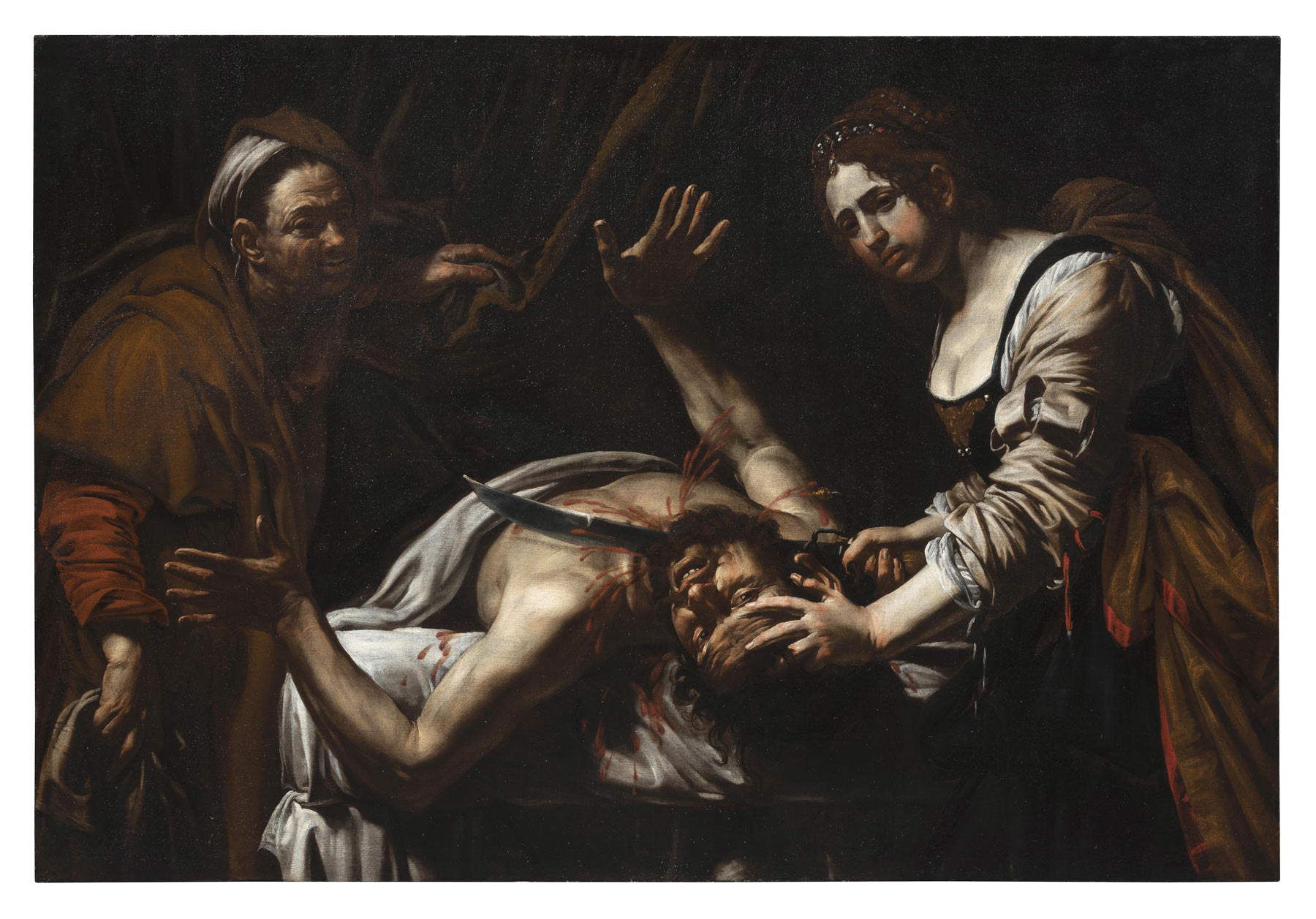

The famous Capodimonte painting crudely depicts the moment of the killing of Holofernes by Judith and her handmaiden Abra: a depiction that is clearly inspired by the famous masterpiece with the same subject created by Caravaggio and preserved at Palazzo Barberini. Artemisia thus chooses to stop on the canvas the exact moment of the beheading and not the frequent representations when the killing had already taken place, with Judith coming out of the tent where the deed had been done carrying in her hands or in a basket the decapitated head of Holofernes.

Maria Cristina Terzaghi argues that the painting became “the scene of an almost total identification” with regard to Michelangelo Merisi’s counterpart painting. As the scholar explains, Caravaggio’s work focuses on theagonized scream of Holofernes, balanced, however, “by the intact beauty of the heroine,” who cuts off the general’s head in an almost composed manner (albeit with an expression of revulsion at the blood spurting from her neck); Artemisia’s, on the other hand, places emphasis on the physical exertion and violence of both Judith and the handmaiden, who help each other, accomplices in the act. While Judith holds the general’s head still with one hand by grabbing him by the hair and with the other forcefully holds the sword to behead him, the handmaiden actively participates in the action, trying to immobilize his arms to make the task easier for the other. Holofernes, however, attempts to escape his fate by grabbing Abra’s collar, although by now the cut has already been made, as can be seen by the copious blood that has already soaked the white sheet on which he is lying. The eyes staring into the void and the half-open mouth also hint that the man is taking his last breath before dying. The strength and impetus that the two women put into the gesture is also underscored by the sleeves of the dresses done up, which leave the forearms of both of them uncovered. This creates a crisscrossing of the three characters’ bare arms, which gives additional dynamism to the scene.

It should also be noted that Artemisia depicts in the Capodimonte painting the two women as peers, unlike Caravaggio, who in his Judith depicts the heroine (in this case the only one to carry out the beheading) as a young maiden, while the handmaiden, a wrinkled old woman, watches the scene in horror with a cloth in her hands within which to hide the general’s head, as if to imprint on her face the horror of any observer witnessing the crude action. Artemisia’s two women differ, however, in the social position expressed through their dresses: blue, elegant and garnished with gold that of Judith, red and simpler that of the handmaiden.

The story of Judith and Holofernes is well known: taken from theOld Testament, it recounts that during the reign of Nebuchadnezzar, the beautiful and wealthy Judith, left a widow, decides to liberate her city, Bethulia, which had been placed under siege for a long time by the Assyrian general Holofernes. Accompanied by her servant Abra, the young Hebrew girl volunteers to go to the opposing camp, pretending that she wants to betray her fellow citizens by revealing their weakness. The general falls for the trap, also convinced that he can possess her; he gives a banquet in her honor and, once back in the tent, drunk on wine, falls sound asleep. At that point Judith, who had entered the tent with him, grabs the sword and decapitates him and subsequently brings the head on display to her people. The latter, on the strength of the woman’s success, finally defeats the Assyrians upset by the death of their general. According to the Old Testament, the handmaiden would have remained outside the tent holding the sack ready to hide the decapitated head, and thus would not have participated as actively in the killing as is seen in Artemisia’s painting.

As for the dating of the Capodimonte painting, it still remains uncertain: it is generally placed at the beginning of the Florentine sojourn as a more or less direct response to the violence suffered by Agostino Tassi or at any rate as a reflection of apsychological elaboration of the fact. Taking into account that the rape trial was held in 1612, it is possible to date the work around 1613, but a hypothesis has recently been put forward by Francesca Baldassarri to date the painting later, to 1617, due to a payment dated July 31, 1617 paid in Florence by the gentlewoman Laura Corsini to Artemisia for a Judith, which the scholar has proposed to identify precisely with the one in Capodimonte.

The theme of Judith Beheading Holofernes was also reproposed by Artemisia Gentileschi inanother version, now in the Uffizi Galleries. Very similar in composition, so much so that scholars were initially divided between those who argued that the latter predated the Neapolitan version and those who argued the opposite, the Florentine version appears more carefully and sumptuously painted than the Neapolitan one. The chronology debate was resolved by technical investigations carried out on the Capodimonte painting, which revealed numerous pentimenti, unlike the Uffizi painting, which lacks them. It is clear, therefore, that the Neapolitan version predates the other. Datable to about 1620, the Uffizi painting also depicts the moment of Holofernes’ beheading by the brave Judith. We find here the crossing of the bare arms of the three characters, the general lying on the bed already stained with blood, the sword sinking into his neck, and the complicity of Judith and the handmaiden Abra, also depicted young here. One notices the different color of the two women’s dresses (yellow Judith’s and blue Abra’s) and the addition of a gold bracelet on Judith’s bare arm, as well as a red drape over Holofernes’ body, but the painter does not hesitate to include a gory detail, such as the splashes of blood that like thick lines come out of the neck and then in scattered droplets until they stain the heroine’s own chest. Finished in Rome, where the painter had returned after her stay in Florence and where she was still able to come into contact with Caravaggesque works, the Uffizi painting, commissioned by Grand Duke Cosimo II de’ Medici, was initially despised for its crude realism, to the point that it was denied the honor of being exhibited in the Gallery. And it was only thanks to her friend Galileo Galilei that Artemisia was able to obtain, albeit with great delay, the compensation agreed upon at the time of the commission from the Grand Duke, who, however, just after the painting’s execution died in 1621.

That the subject of Judith and Holofernes was dear to Artemisia as even minimally related to her personal experience is inescapable, but regardless of the exact dating and recent reinterpretation according to the art-historical context of the time, Judith Beheading Holofernes is one of the greatest masterpieces in the history of art of all time and a clear testimony to an independent woman artist who made her place for her high pictorial skills in a purely male world.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.