Ilaria del Carretto's monument, the beautiful tomb in Lucca Cathedral

One enters the sacristy of the Cathedral of San Martino in Lucca in respectful silence, to pay homage to that young woman who has been lying on her sarcophagus for more than six hundred years. The cathedral holds masterpieces by important artists inside, think of Tintoretto’sLast Supper, Fra’ Bartolomeo ’s Madonna and Child between Saints Stephen and John the Baptist, or even the famous Holy Face, which is highly venerated, but the Funeral Monument of Ilaria del Carretto by Jacopo della Quercia (Siena, c. 1374 - 1438) is one of those works that creates a sense of temporal suspension between the effigy and the observer: it seems that that smooth white marble is really the very white skin of the unfortunate young woman who died prematurely at the age of only twenty-six, and that long dress she is wearing is of real fabric. It seems therefore that that beautiful creature really remained like that, as if “frozen” in an indefinite and infinite time, never to lose its beauty. It is a work that never ceases to enchant, even if one admires it over and over again, even from a distance of time.

It is her extraordinary realism that is probably her secret: her well-characterized face, with features so distended that she seems to be in a perpetual sleep; her hair gathered under a padded headband decorated with leaves and flowers in atypical noblewoman’s hairstyle, which, however, leaves small curls loose on her forehead; her neck completely covered by the high collar of her dress, which keeps her rigid in that position. The dress, a pellanda typical of Franco-Flemish costume, clings to her body, shaping it, and creating very lifelike folds. Long to the bottom of the feet and beyond, it is cinched under the bust by a sash, slightly marking the shape and creating small ripples in the fabric, and from two side slits come out wide puffy sleeves ending in narrow cuffs. The arms are long stretched across the body, with the hands crossed over the belly.

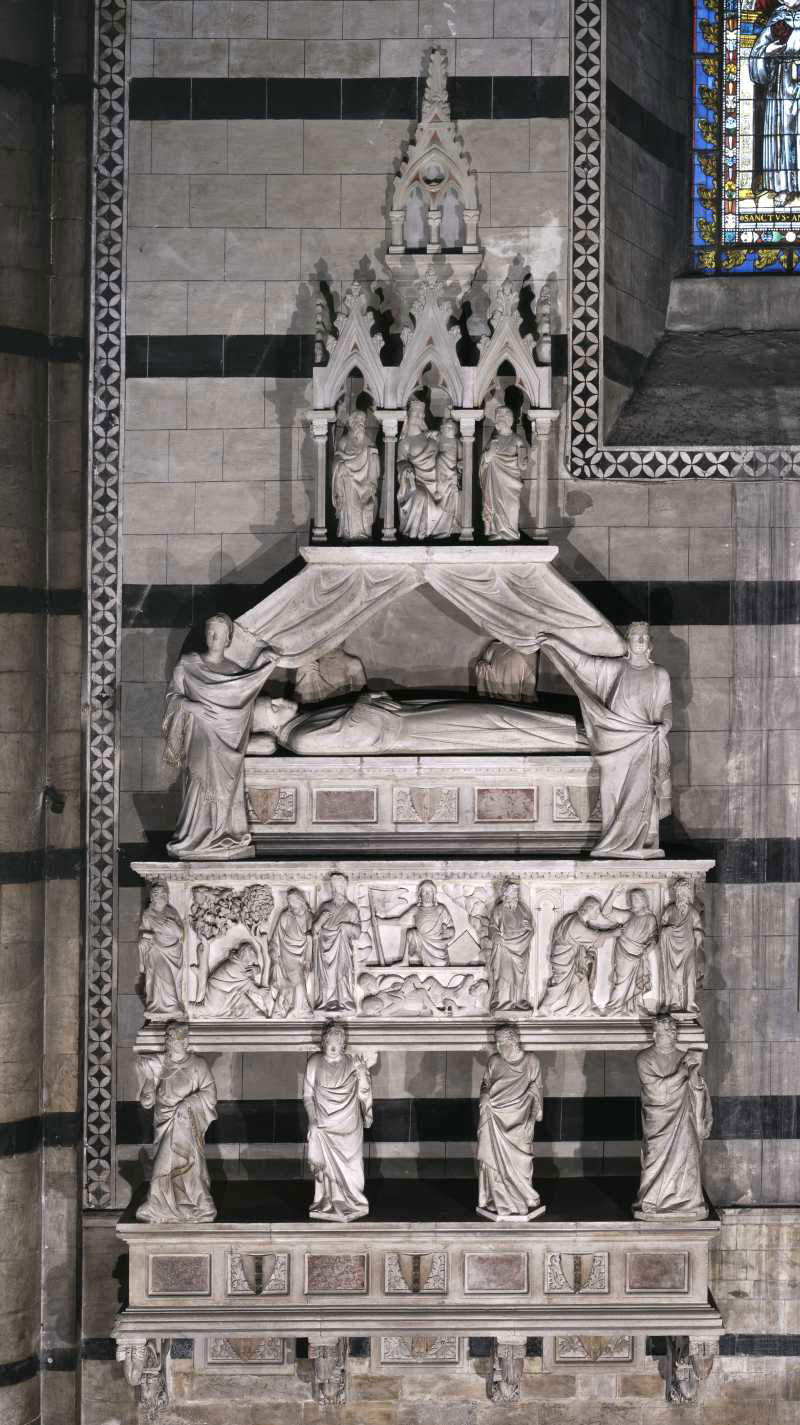

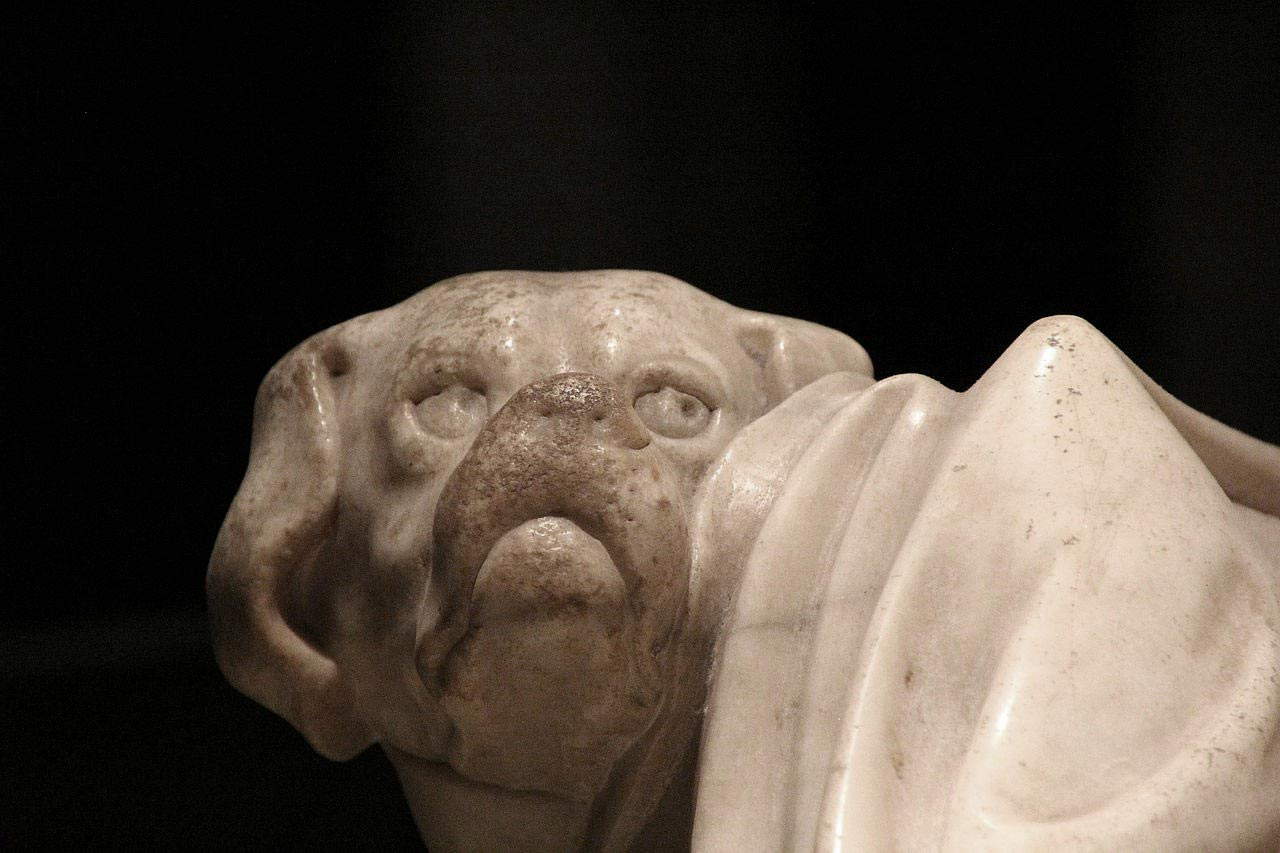

Representing a deceased woman in her funerary monument in this way was, for Italy in the early fifteenth century, a novelty, since up to that time funerary monuments, think of those of Arnolfo di Cambio (Colle di Val d’Elsa, c. 1240 - Florence between 1302 and 1310) or Tino di Camaino (Siena c. 1280 - Naples 1337), the latter already with innovative impulses, saw the body of the deceased to whom the monument was dedicated lying on a sort of canopy within a more complex structure, enriched by the presence of other figures, and leaning against a back wall of a church. Examples are the Funeral Monument to Cardinal de Braye by Arnolfo di Cambio or the Monument to Cardinal Riccardo Petroni by Tino di Camaino. In the Funeral Monument of Ilaria del Carretto, on the other hand, Jacopo della Quercia created between 1406 and 1410 aunique, unprecedented, three-dimensionalwork, around which the observer can turn so as to see it in the round, on all four sides. The sculptor, renewing the language of Sienese Gothic sculpt ure by interweaving it with Burgundian sculpture and classical elements, places the young woman’s body on a high plinth made up offour decorated slabs and has her head held slightly elevated by two cushions, one larger and one smaller, also made of marble, of course. He also places a small dog, a symbol of marital fidelity, at Ilaria’s feet, which is crouched on the surface but with its muzzle raised as if waiting for any nod from its mistress.

The general setting of the funerary monument is related to French matrix typology in terms of the reclining figure, the crossed hands, the small dog at the foot of the deceased’s body, and the garb typical of an elevated social class of Franco-Flemish culture; and the drapery refers to late Gothic Burgundian sculpture. The sculptor thus demonstrates a close connection with the taste of the International Gothic, but to this is added a more humanistic sensibility clearly visible in the rendering of the face and a homage to the classical tradition with regard to the festoons supported by putti on the long sides of the base. These two slabs, one executed by Jacopo himself and the other by one of his close collaborators, are in fact adorned with festoon-bearing put ti that recall ancient sarcophagi, particularly those of the Hadrianic age, but unlike the latter, the artist depicts fewer of them here (three on each side) to make the composition less crowded. On each corner he then adds another putto, for a total of ten putti. On the short sides of the base, on the other hand, an arbored cross is depicted on one side and a shield with the united coats of arms of the Guinigi and Del Carretto families.

In fact, the sculptural masterpiece was commissioned from Jacopo della Quercia by Paolo Guinigi, lord of Lucca from 1400 to 1430 and a patron of the arts, as a tribute to his second wife, Ilaria del Carretto, who died during her second childbirth at a very young age of only twenty-six. Daughter of the marquis of Zuccarello in Liguria, Ilaria married Paolo in February 1403, and on December 8, 1405, the misfortune occurred. The monument was made between 1406 and 1410, but the sarcophagus was probably already near completion in April 1407, when the lord of Lucca remarried.

Paolo Guinigi married four times, or rather three, because the first, the very young Maria Caterina Castracani degli Antelminelli , only eleven years old, was only “betrothed” as she died of the plague a few months before the wedding. Instead, he married, as has already been recounted, the marquise Ilaria del Carretto in 1403 with a “smizurata festa in Santo Romano,” as Giovanni Sercambi records in the Croniche, which immediately gave her an heir, Ladislao, born the following year; on December 8, 1405, instead, her second daughter was born, who was given the same name as her mother, but as a result of complications in childbirth the young woman died shortly afterwards. Paolo Guinigi’s third woman was Piacentina di Rodolfo di Varano, daughter of the lord of Camerino: after giving birth to five children in nine years, she too died in 1416. His last marriage was celebrated in 1420 to Jacopa Trinci, daughter of the Lord of Foligno, but she too died shortly after giving birth along with her daughter.

Guinigi’s marriages were always conditioned by political choices; even his union with Ilaria del Carretto, which would have created greater understanding with the Visconti of Milan, given Del Carretto’s support for the latter. However, undoubtedly, Ilaria was the woman to whom Paolo felt most attached, given his choice to dedicate the wonderful funeral monument to her, with the little dog symbolizing fidelity and the coats of arms of the two families united. The monument actually never held the woman’s body; during recent studies conducted by the Division of Paleopathology of the University of Pisa on the burials found in the Chapel of Santa Lucia, annexed to the complex of San Francesco, used as a private and funerary chapel by the Guinigi family, the remains of an adult woman of rather puny build of an anthropological age between twenty and twenty-seven years were found that could be attributed precisely to Ilaria, but there is no certainty.

The sarcophagus was mounted in the right transept of the cathedral, in front of the altar, now no longer extant, of Saints John and Blaise, patroned by the Guinigi. After several moves inside the Cathedral of Lucca, since December 1995 it has been placed in the Sacristy, where it is still located, following stability problems detected in the walls of the left transept where it had been since 1842, and the subsequent consolidation work that lasted several years.

“Thou seest far away the gray olive groves / that vaporise the face to the hillocks, O Serchio, / and the city from the arboreal circle, / where the woman of Guinigi sleeps. / Now sleeps the white cornflower / enclosed in cloths, lying in on the lid / of the lovely sepulchre; and you had her to mirror / perhaps, had your shore its vestiges. // But today not Ilaria del Carretto / rules the land you bathe, / O Serchio.” Thus poet Gabriele D’Annunzio in Elettra, and Salvatore Quasimodo titled Davanti al simulacro d’Ilaria del Carretto a poem contained in Ed è subito sera, and again, Pasolini in the poem L’Appennino, in The Ashes of Gramsci, wrote “Jacopo with Ilaria sculpted Italy / lost in death, when / her age was purest and most necessary.” Honored in literature and loved and admired in art, Ilaria del Carretto with her famous Lucchese funeral monument will still live on in eternity.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.