The stubborn need to connect audiences and works, to bring art closer to enthusiasts, has primarily driven artists from the 2000s onward to decline their creativity in a distinctly three-dimensional sense. To make, in essence, mainly sculptures, videos and installations. An approach, even keeping out of metaphors and cultural elaborations, that has physically contributed to make works closer and more tangible, even at the cost of sacrificing languages usually more accessible and usual. Above all, painting, which only in the last five years has returned to appear more consistently in the most relevant showcases for a young artist (galleries and fairs). A need, going back to the predominance of sculptures and installations, however, that also intercepts the spirit of the times, at least the more open and experimental one, devoted to the search for new forms and solutions.Installation, in particular, well expresses other irresistible desires of contemporary man: spectacularization, hybridization, versatility. An art form that therefore, in spite of the skepticism of the more conservative segment of the public, fits perfectly into its era.

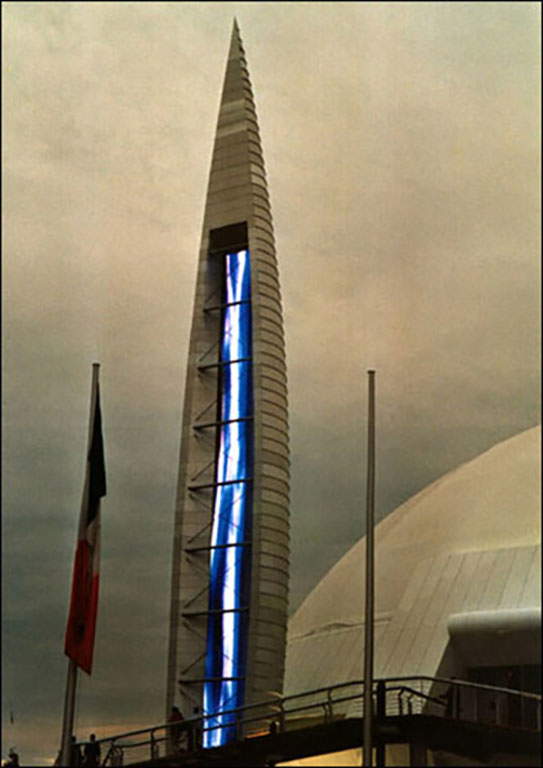

But if of the evolving world we often praise the cyclical nature (which is leading to a return of the most persevering of artistic mediums, the aforementioned painting), equally compelling is its unpredictability. Thus the same progressive flux that spurred the rise of installation has led to an alternative almost at the antipodes: video art. Going along with the technological sprawl that has capillarily occupied almost every sphere of our existence, Italian art has also deepened its relationship with digital media. Among these, the most intuitive and easily explored - either because of its relationship with cinema, or because of the linear transition from static image (painting) to moving image - immediately turned out to be video. The perfect hinge between these two experiences was undoubtedly Fabrizio Plessi (Reggio Emilia, 1940), who combined both of the above-mentioned expressions with his famous video installations. In 2000 he created for the Italian pavilion at the Hanover Expo a monumental 44-meter-high installation called Mare verticale, which represented a continuous flow of blue water, which flowed uninterruptedly like a river in flood. A solution, this one of the flow of matter and color, that Plessi has reproposed often over the years, even at the latest exhibitions at the Palazzo Reale in Milan(Plessi. Mariverticali) and at the Santa Giulia Complex in Brescia(Plessi Sposa Brixia).

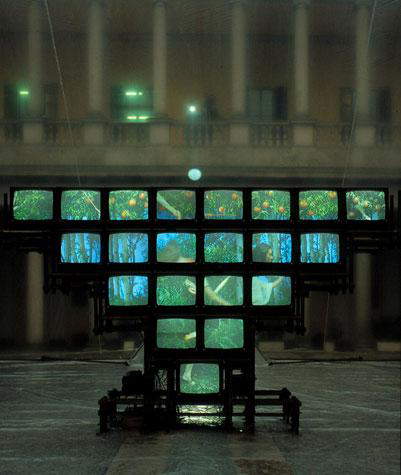

Even earlier, but equally illustrious, are the examples of Marinella Pirelli (Verona, 1925 - Varese, 2009) and Studio Azzurro. The former was an acute experimenter in the Italian visual language and led to pioneering results in the field of experimental cinema, through films played on balances between color and abstract forms that take their start from meditation on luminous phenomena and the refraction of light(Double Self-Portrait). More broadly and systematically, the Studio Azzurro collective, established in 1982, has also shown a possible way to integrate the technological medium, particularly video, into the art world, with the creation of video environments(Two Pyramids), sensitive environments, museum itineraries, theatrical performances and films.

Coming specifically to our period of analysis, among the authors who have most successfully focused on this type of language are undoubtedly MASBEDO, an artistic duo formed by Nicolò Massazza (Milan, 1973) and Iacopo Bedogni (Sarzana, 1970). The two have been working together since 1999 and have before others grasped the great potential of the new medium: bringing together different artistic languages (video, installation, cinema, performance, avant-garde theater and sound design) in a single solution. At the content level, their main skill is to make a careful look at socio-anthropological elements coexist with the more intimate and poetic elements of human experience. A clear element of contact with Relational Art that we have discussed at length earlier. As is the case in Theorem of Incompleteness, a work that inaugurates Masbedo’s Icelandic sojourn (2008) and narrates the difficult relationship between a man and a woman through the destruction of fragile crystal and glass objects - set against the backdrop of an Arctic landscape - that metaphorically symbolize the dissolution of the sacredness and intimacy of the pair of lovers. Broadening the perspective, the video suggests how desire, understood as a contemporary yearning-neurosis, the sole driver of all capitalist Western societies, is capable of atrophying the sense of existence. Rosa Barba (Agrigento, 1972) also exploits video as a container-expression of different language and sources, from archival research to travel, from reading to writing. Almost didactic in this sense is the work From Source to Poem (2016), a film shot in the United States that collects images from the world’s largest multimedia archive, the Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation of the Library of Congress, located in Culpeper, Virginia, and assembles them into a densely layered audiovisual narrative in which, as in white noise, each element is progressively overlapped and condensed. In sum, the work is an invitation to think about the spaces in which history and cultural production are preserved to be passed on to future generations.

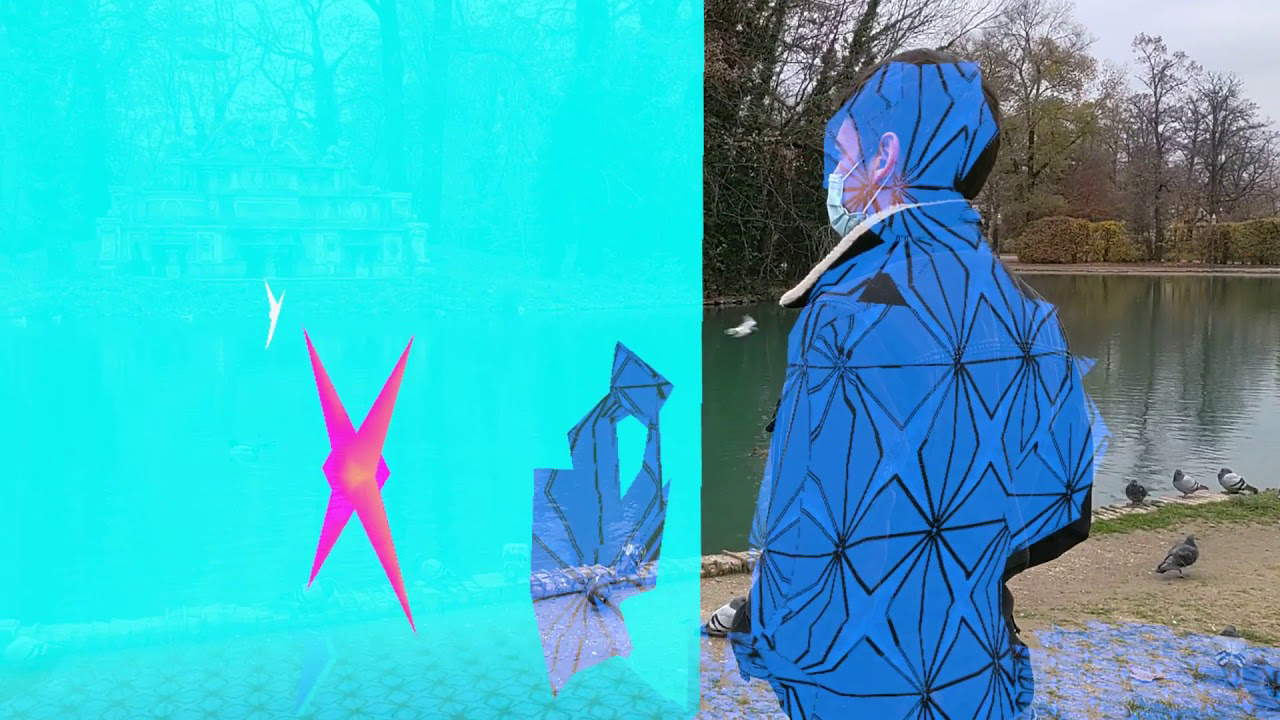

A context in which Yuri Ancarani (Ravenna, 1972), who gives his video works a clear documentary slant, also successfully fits in. Active since 2000(Memories for Moderns, 2009), the artist has made numerous important works over the years(The Iron Disease, 2010-12; The Roots of Violence, 2014), up to the success of the feature film Atlantis (2021), awarded Best Documentary at the David di Donatello 2022 (and nominated at the Venice Film Festival in the Orizzonti section). Vincenzo Marsiglia (Belvedere Marittimo, 1972), on the other hand, reflects insistently on the relationship between tangible and virtual realities, starting with a pictorial background and then experimenting with various digital solutions throughout his career. In particular, the artist’s path is linked to the formulation of a distinctive code, the four-pointed star, the EU - Marsiglia Unit, which becomes a recurring symbol in his iconographic repertoire. The obsessiveness of the repetition of this symbol was expressed through fabrics, ceramics, stone, glass, paper, articulating itself according to continuous variations of rhythm and form. He then also landed on a wide range of digital media: lcd monitors, ledwalls, viewers, artificial intelligence and especially video(Holo Private Immersion). Aesthetically, his work can be approached as Geometric Abstraction, Minimalism and Optical art.

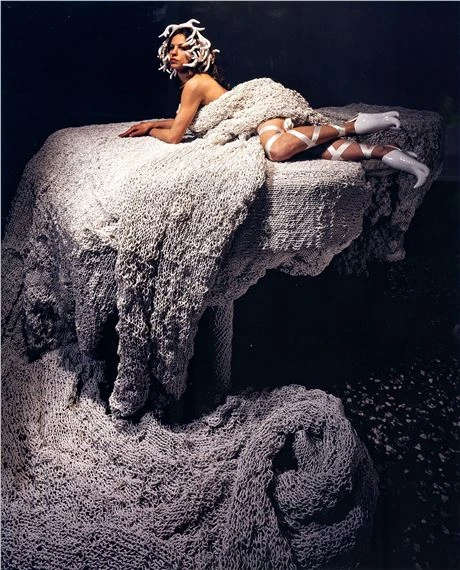

In the same particular way that the sculpture-installation has dematerialized into video, video has in parallel helped to restore matter-or at least testimony-to the artistic expression that par excellence lives on an ephemeral taste: performance. Absolutely to be understood in a sense supplementary to, and not a substitute for, the actual happening, it is undeniable that video counteracts the evanescence of performance by opening an additional (and perpetual) window of fruition. Without it, we would not be able to relate to Sissi ’s (Daniela Olivieri; Bologna, 1977) performative experiences, which from her earliest years see the artist making nests or cocoons by hand working with knits, plastic and other materials, which often take on the function of clothing. As in Daniela missed the train (1999), where Sissi wore a skirt made of tires that prevented her from boarding a train; or La di piano (2002), in which enameled ceramic elements depicting a crown and a pair of milky-colored clogs shaped an imaginative vision of a being at once real and hybrid. In her poetics, clothing is not a mode of appearance, but a vehicle for continually staying in touch with the world. His modes of making and his aesthetic thus allow us to communicate in ways that are both precise and evocative.

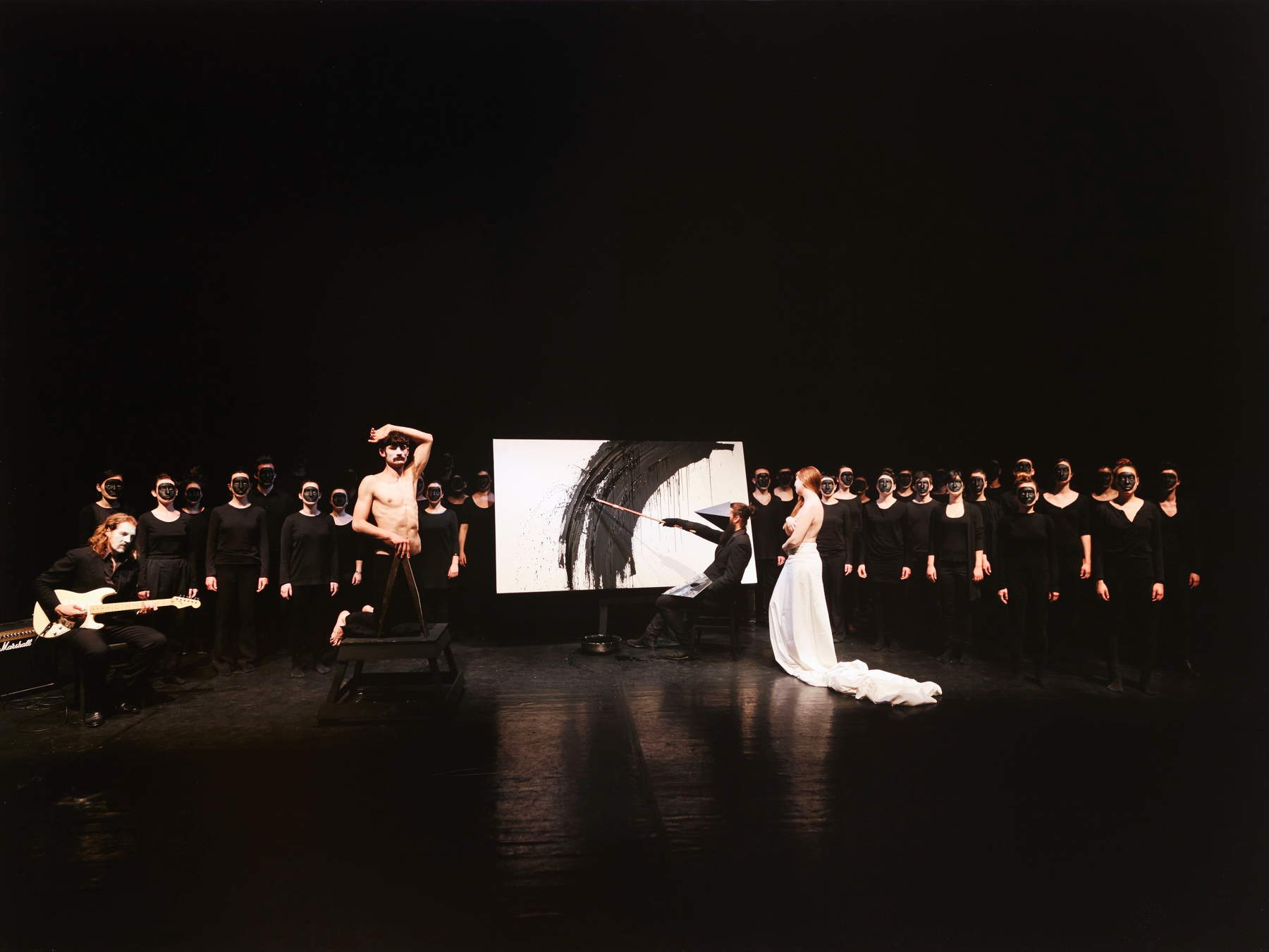

Equally impactful are the performances of Nico Vascellari (Vittorio Veneto, 1976), who exploits, however, music (and particularly his voice) as a method of expression. Set up in urban or museum contexts, the works boast a structured symbolic apparatus aimed at evoking a layered imagery that conveys a kind of primordial energy. Exemplary in this sense is I hear a shadow (2009-2010), in which Vascellari uses the cast of a giant bronze rock as a sounding board for his ritualistic actions. Ritual, and the repetition attached to it, explode in the live stream DOOU (2020), which the artist undertakes during the period of pandemic confinement and in which for 24 hours he repeats the phrase “I trusted you” to launch his CODALUNGA YouTube channel. An operation in which multiple issues were included: political, social, artistic, narrative, technical, advertising, and more. Rituality is also dealt with in the performances of Luigi Presicce (Porto Cesareo, 1976), adept at combining pagan apotropaic rituals with iconographic references to fourteenth-century medieval frescoes, or evoking fascist gatherings and Masonic meetings and contaminating it with references to ancient and distant cultures. Such aesthetic flashes are often condensed into tableux vivants with a metaphysical and surreal character, rich in allegories and symbolic allusions to esotericism, religion and the traditions of his land, Salento. The examples, in this sense, are numerous: The Annunciation of Pythagoras to the Acusmatics (2010), King of the World under the Sky of Earth (2014), Abstract Allegory of the Painter’s Atelier in Hell among the Twin Spikes (2014).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.