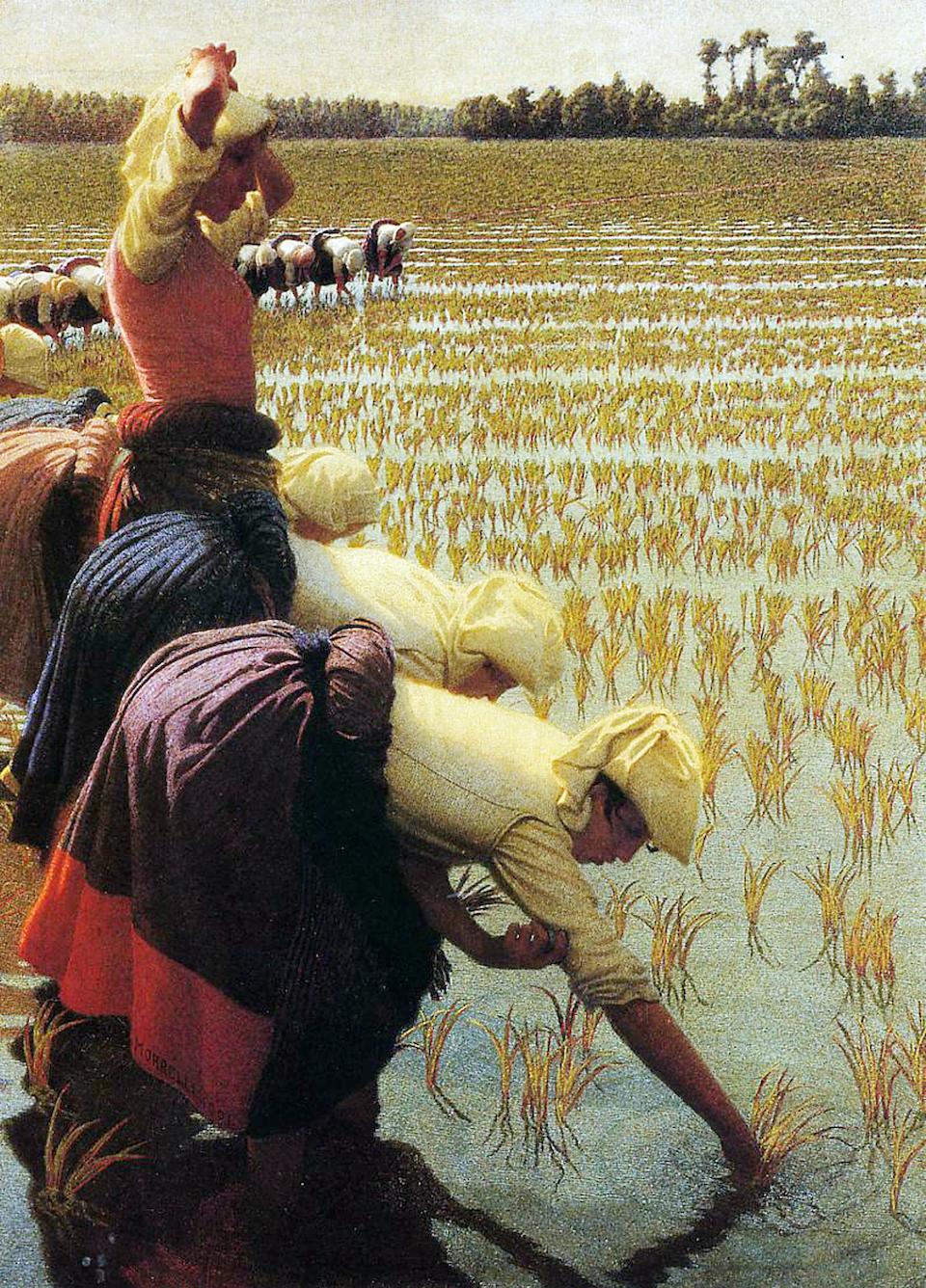

On January 18, 1895, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo wrote to Angelo Morbelli (Alessandria, 1853 - Milan, 1919) to congratulate him on his progress with the work the artist was making at the time, his masterpiece Per ottanta centesimi!, now preserved in the Borgogna Museum in Vercelli. “Delighted that your painting 80 cents is progressing well,” Pellizza wrote to his friend: Morbelli had begun it in 1893, but two years later it was still being worked on because the artist intended to exhibit it at the first edition of the Venice Biennale, where it actually went. The painting was then exhibited in 1896 in Turin and in 1897 in Dresden. It is a matter of debate whether the painting was reworked with a view to an exhibition at the Brera Triennale in 1897, where Morbelli presented another painting intiolato In risaia: perhaps, more simply it was a different work (indeed we know of another one with this title).

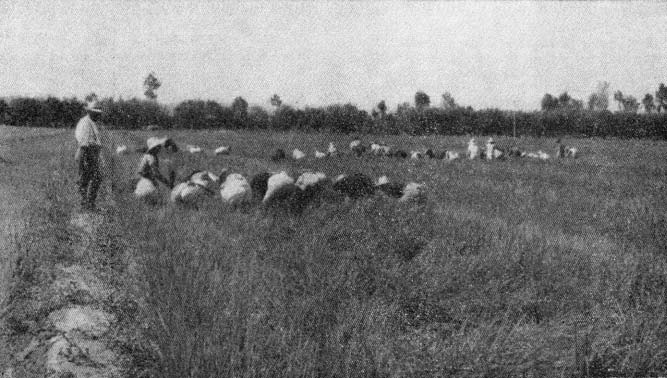

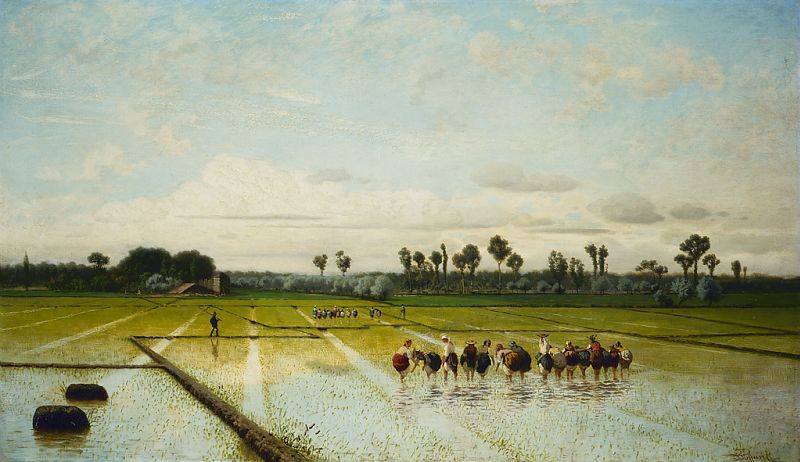

The work, which has become almost a symbol of late nineteenth-century Italian painting and in particular of that strand animated by intentions of social denunciation, takes us to a rice field, foreshortened in perspective from below, so much so that on the horizon we do not see the sky, but only a line of trees: we are in the plain between Casale Monferrato and Vercelli, where it is not uncommon to come across green patches lined up at the end of an expanse of meadows or rice fields. The protagonists of the painting are the mondine, the women who worked in the rice fields, with water up to their knees and their backs bent, to remove the weeds that grew in the paddy fields and could jeopardize the growth of young rice plants. From this activity comes the name: the mondine were the workers who “mondavano,” or cleaned, the field on which the rice would grow. It was very hard work: it was typically done in the last two months of spring, and forced the women who did it to spend hours bent over in the water. It was therefore practiced by women of low social status who came to the rice fields of Vercelli and nearby Novara and Pavia from much of northern Italy.

The Borgogna

The Borgogna Mondine at

Mondine at

It was, in fact, a seasonal job that also attracted women from the Veneto and Emilia-Romagna regions. Indeed, internal migrations were well received by landowners, since, the report of a conference on the working conditions of the mondine held in Bologna in 1905 (and reported in the Bollettino del Lavoro e della Previdenza Sociale) states, the local women workers wanted to render their services only in return for “a fair wage and hours that are not detrimental to their health.” thus, with the intent “to leave the local rice-workers unemployed,” paddy field owners were hiring “foreign personnel” willing to more nerve-wracking working conditions. At the end of the conference, it was determined that the unions should work to make sure that contracts did not exceed 11 hours of work per day and that they complied with the “Cantelli regulation”, to make sure that there were no abuses by landowners, that the feeling of solidarity was strengthened among workers, that the issue of seasonal migrants was discussed in the press and through “oral propaganda,” and that a conference was held at the end of the monda season to assess progress. Cantelli’s regulations, enacted in 1869, stipulated that work should begin one hour after sunrise and end one hour after sunset (for an hourly day of about nine hours), and prescribed hygiene rules to prevent the mondine from falling ill. Often, however, the regulations were not adhered to, and the mondine were forced to work for up to twelve hours a day, well after sunset. The wages of the mondine, to which the title of Morbelli’s painting refers, were abysmal: from a letter from the sub-prefect of Vercelli dated July 13, 1901, we learn that from a day’s work the mondine earned between 1.2 and 2.1 lire, corresponding to about 5.37 and 9.4 euros today. By contrast, the eighty cents per day referred to by Morbelli in 1895 was equivalent to today’s pay of 3.5 euros: at the time the Piedmontese artist painted his work, the price of rice had plummeted due to a severe crisis, and as a result many landowners had passed on lost earnings to labor costs. One can therefore well imagine the miserable conditions in which the women who worked in the rice fields lived: dilapidated houses, situations of widespread promiscuity, extremely poor hygiene, children often following the mondine even to the workplace, and therefore forced to play in the rice fields. In the catalog of the exhibition that Alessandria dedicated to Morbelli in 1982, curated by Luciano Caramel, scholar Maria Luisa Caffarelli recalled how in 1901 the union delegate to the Congress of Agricultural Leagues in Novara, Romolo Funes, speaking of the migrant workers arriving in Piedmont from other regions, said: “It should be known that we have in the Oltreticino a quantity of wretches who for 60/70/80 cents a day come to ruin all our, comrades, all our work.” One might assume, then, that it is precisely these female workers who are the protagonists of the painting, underpaid compared to already very low wages on average.

For eighty cents! not is, however, the only painting in which Morbelli addresses the theme of the mondine. Another painting, In the Rice Field, from 1901, was long on display at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, to which it had been granted by its owner, who then decided to sell it at auction in 1995. And recently a painting from 1897, also from a private collection, titled Risaiuole, resurfaced, which went to auction at Bonhams in 2017 (where it sold for £173,000) and was exhibited for the first time in more than a hundred years in 2018 at the Museo Borgogna in Vercelli in an exhibition curated by Aurora Scotti Tosini, a leading Morbelli expert. In the Risaiuole, the mondine are presented exactly as in Per ottanta centesimi!, a work in which Morbelli decides to bring us into the reality of the rice workers in a totally unusual way: in fact, we see them from behind, all bent over, with their handkerchief tightly on their heads to shield themselves from the sun and to avoid mosquito bites, lined up as they used to work, occupying the lower register of the painting, close to the vantage point of the relative, in an area of the rice field where there are still few plants and the artist’s skill can focus on the reflection effects of the figures on the water. The perspective construction is suggested by the canals that furrow the paddy field, while in the distance, on the left, we observe another team of mondine intent on performing the same, wearisome task as their colleagues in the foreground.

The way Morbelli presents the work of the mondine apparently contrasts with the title, which suggests a desire for social denunciation, so much so that this contrast has generated discussion among scholars about Morbelli’s intentions. Michael Zimmermann, for example, coined the term “perspectivism” to denote what he believed was the artist’s method: “everything in his vision,” wrote the German scholar, “depends on his point of view: that of a painting addressed to the human eye carefully studied in physiological temini; that of a perception conditioned by cerebral as well as cultural models [...]. In a painting, as in a text, there is always a point of view of the narrator. Morbelli, however, does not impose this point of view as already predefined on the viewer.” And the way to avoid imposing his point of view would be precisely the “cold pictorial construction” of the painting, with which the artist invites the audience to form its own idea about what is happening, its own “perspective,” in short. On the other hand, it should be mentioned, however, in addition to Morbelli’s declared socialist sympathies (he made his position explicit in an investigation conducted in 1893 by his friend Gustavo Macchi), that some scholars, such as Aurora Scotti Tosini, have emphasized the fact that the pose of the mondine serves to emphasize the toil of their work, and at the same time the reiteration of the group in the upper left corner would be intended to amplify this feeling. We have no doubt, however, that the painter sympathized with the women workers, and the debate is, if anything, about the nuances the artist’s work takes on: one could call Per ottanta centesimi! a work of social denunciation that is, however, devoid of any propagandistic intent.

What is certain is that Morbelli also saw his painting as a very innovative work from an artistic point of view: in fact, the artist was firmly convinced of his own Divisionist language, of the experiments he was conducting in those years to convincingly render luministic effects on canvas, based on the idea that a scientifically conducted investigation of color could bring the work closer to the truth. On the occasion of the centenary exhibition that the GAM in Milan dedicated to Morbelli in 2019, an unpublished letter to the sunnominated Gustavo Macchi was published, undated but placeable around 1910, in which the artist expressed his own on pointillism, saying: “for me it has a law like perspective, it is a resource like veiling, it certainly gives a transparent vision due to the phenomenon of the different lengths of undulation that reach the eye, and I think I can say (with an almost certainty), it gives a greater feeling of... planes.” And pointillism was for Morbelli “an advance in the vision of representational art.”

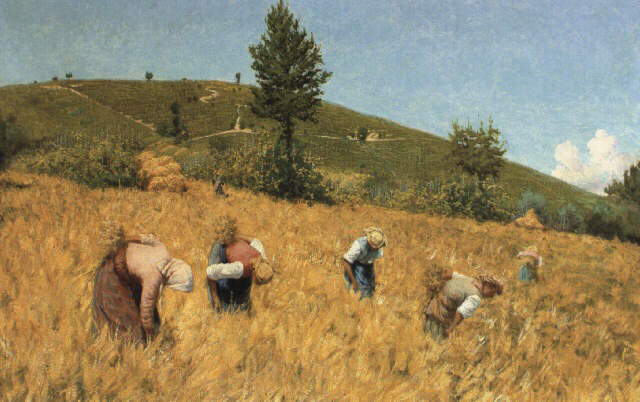

The artist had previously addressed the theme of women’s labor in the fields, as in the Reapers placed around 1885, but the conception that animates For Eighty Cents! is entirely new. The point of departure for his reflections are always the French naturalists, above all Jean-François Millet, who in 1857 had painted the celebrated Spigolatrici (Gleaners ) now in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. Morbelli, meanwhile, zeroes in on the monumental plasticism of the Spigolatrici, thus stripping his image of any “epic” aura that many perceive in the French painter’s painting. And then he also decides to do more. It is necessary, meanwhile, to premise that he was not the first painter to take an interest in the work of the rice fields: in 1864, Luigi Steffani painted a work entitled In the Rice Field that can be considered the most direct antecedent of Morbelli’s painting: however, Steffani’s main focus was on the landscape, and evidence of this is the fact that two-thirds of the composition is occupied by the sky, while the mondine appear much farther away than in Morbelli’s. The originality of the Alexandrian painter’s painting thus lies also in the photographic cut chosen to “frame” the mondine, a cut that does not admit the presence of the sky and thus makes the composition much more oppressive, taking away space from any possible yielding to sentimentality: Morbelli, as Aurora Scotti Tosini has written, “gave the scene a character of more obsessive fatigue than had appeared in previous depictions of rice paddies.” To arrive at this composition, the artist had initially taken to studying the mondine from life, then given the conditions of the rice fields, difficult even for a painter, he had decided to make use of the photographic medium (Morbelli was one of the first painters to use the medium of photography for his paintings). And it was precisely the use of photography that was one of the two problems (the other was studio lighting) that his friend Pellizza da Volpedo reproached him for, in an undated letter but written while Morbelli was working on Per ottanta centesimi!: “the second cause which is the most important and which to tell you requires all the courage that comes to me from the friendship that unites us and from my conscience as an artist is this,” Pellizza premised: “the reminiscence work that you have adopted in your last paintings, namely the rice field and the mountain that is in Florence. You made the rice field by going sometimes to see it near Casale and then returning home to work the painting from memory, you conducted the figures by making use of photographs.” Pellizza himself had largely made use of photographs, but had then changed his mind, believing that the result was then too detached, and therefore saw the use of photography as a flaw.

Yet, For Eighty Cents! is one of Morbelli’s most complex works: the artist employed a particularly elaborate divided brushstroke (analyses performed on the work for the 2018 exhibition at the Borgogna Museum revealed that Morbelli used up to seven pure colors per square centimeter), distributed in tiny filaments over the entire surface of the painting to give the whole those vibrant effects of light that the artist insistently sought. His innovations, however, were not immediately understood, and evaluations of the painting when he exhibited it at the Venice Biennale were mostly negative. In a review of that first Biennale that appeared in the newspaper Nuove Veglie Veneziane, written by Angelo Muraro who was defending Morbelli, one could read, "It must not be forgotten that the mockery of the philistines turns to Morbelli also for a quite different reason : because he belongs to that school of the new technique, of the so-called pointillé, which paints according to the optical theory of the prismatic composition and recomposition of colors. How good people laugh at it ! And indeed, this technique appears strange and sometimes even repugnant to the eye: but, like it or not, it achieves singular effects." To understand what the tone of the criticism was, one can take as an example what the scholar Antonio Carlo Dall’Acqua said in a reading on that Venice Biennale, given at the Accademia Virgiliana in Mantua. Dall’Acqua had well grasped Morbelli’s intentions of social denunciation, but like most critics, he had panned the technical execution: "Morbelli in his canvas Ottanta Centesimi with lively coloring paints a host of women, who for such petty wages jeopardize their health in the rice fields, with the sun concente on their heads, the stagnant water at their feet. But he did not put in it the mugginess burdening all things; that mugginess that veils all colors, that makes all blades of grass wither, so oppressive as to arouse compassion for the poor mondine working there. Instead, he goes so far as to caricature in aligning on the foreground stoops all of them in such a way as to present the viewer with nothing more than certain unaesthetic back curves, which moreover in their indiscreet development are doubled, reflecting on the water." After all, if still in 1910 Morbelli, writing to Macchi, reiterated that the divided brushstroke would be a conquest of the future, it was clear that critical acclaim was still far from coming for the Piedmontese painter, who is nonetheless recognized today as one of the most original artists of his time.

As for the mondine, however, their working conditions would improve shortly thereafter. As early as 1896, the first agitations were recorded in the Vercelli area, in the rice fields of Bianzè, and shortly thereafter laborers and mondine from other towns in the area would follow suit. In June 1900 some 300 rice-workers went on strike to demand a wage increase (there were two arrests at the end of the day), while an even larger strike, involving almost all the rice-growing localities in the Vercelli area, was called for March 1902. A press campaign ensued denouncing the severe conditions of the workers, and in 1903 a circular was issued by the Ministry of the Interior and the Ministry of Agriculture recommending that prefects be vigilant to ensure that paddy field workers enjoyed sufficient hygiene, performed their work in compliance with the regulations that mandated the start of activities one hour after sunrise until and end one hour before sunset, and did not go into the water without proper footwear. The following struggles, which made extensive and massive use of the tool of the strike, claimed the eight-hour work schedule, which was won by the rice-workers and rice-field laborers in the summer of 1906, a year that began with widespread strikes and culminated between May 31 and June 2 in Vercelli with the “barricade” riots (three days of unrest that led to 26 arrests). It was during these years that the famous folk song Se otto ore vi sembran poche was born: which became popular in the 1910s, when agitations for the eight-hour workday were rampant throughout Italy, it had actually arisen as a protest song of the mondine. In any case, the effects of the rice workers’ protests led, starting in August 1906, to the signing of agreements in several municipalities in the Vercelli area, in which the eight-hour workday was established with average wages exceeding two liras everywhere. In Italy, the eight-hour conquest would be enshrined in law during the Red Biennium, in 1919, while in the rice fields of Vercelli it had already come thirteen years earlier. Thus we owe to the women workers painted by Morbelli in his masterpiece one of the most important social conquests of modern Italy. And art, with Morbelli, had made its own contribution to the cause.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.