Domenico Veneziano's Magnoli Altarpiece: when Florence discovered light.

There is a primacy to be accorded to the Santa Lucia dei Magnoli Altarpiece, better known, more simply, as the “Magnoli Altarpiece,” the masterpiece by Domenico Veneziano (Venice, c. 1410 - Florence, 1461) preserved in the Uffizi. A premise is necessary, however: the work of the Venetian artist is set in one of the most revolutionary moments in the history of art, the period in which the concept of the “altarpiece” was radically reformed, with the gradual move away from the polyptych and the adoption of new solutions that favored the new iconographic motif of the sacred conversation, in which all the saints share a unified space, which is articulated in a credible way, foreshortened perspective in depth. In other words, the new altarpieces tend to define their places, increasingly imposing the use of painted architecture. Adding to the fiction, wrote the great art historian André Chastel, "are above all the marble pavements, the ideal checkerboard of perspectives, which ’stretch’ the ground like a mathematical continuum to the horizon, so much so that the relationship of the figures to this perfect support seems similar to that which binds the church pavement to the inescapable play of axes, suddenly made manifest.“ Chastel credited the Magnoli Altarpiece with being the first work to introduce this ”subtle and seductive effect," inaugurated precisely by Domenico Veneziano.

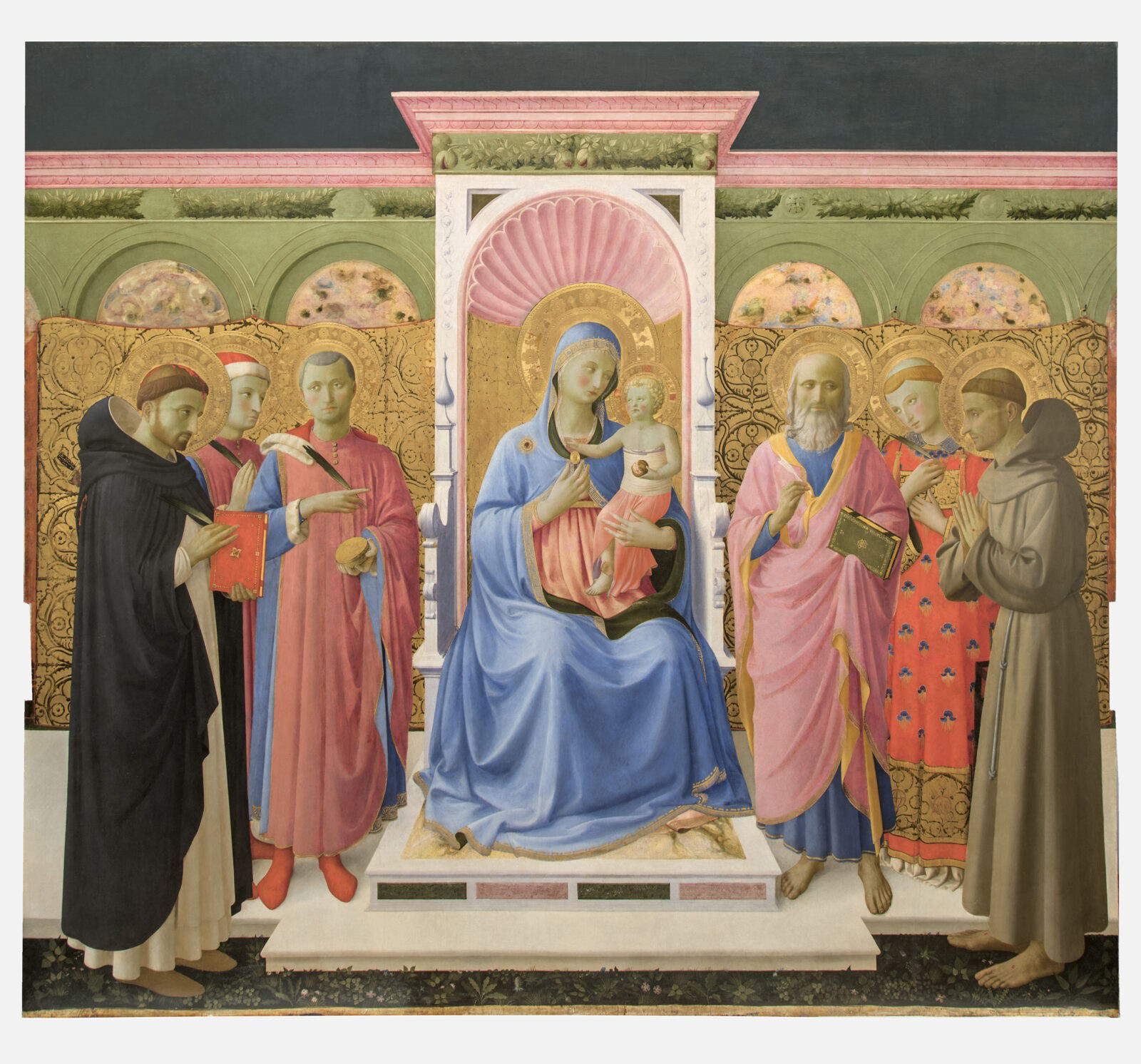

The Magnoli Altarpiece is one of the rare surviving works by this seminal 15th-century master. It was painted between 1445 and 1447 for the church of Santa Lucia dei Magnoli in Florence, where it remained until 1862, when it was transferred to the Uffizi, but we do not know exactly when it was executed. Here, too, we are in the presence of a sacred conversation: the Virgin is seated on a throne with the Child, depicted standing on his right knee, holding his arms around his mother’s neck, and she is supporting him with her right hand, while with her left she caresses his feet. Standing beside her are four saints, two on each side, arranged in a semicircle: St. Francis and St. John the Baptist on the left, and St. Zanobi and St. Lucy on the right. Francis is caught in the act of reading, while John the Baptist has the task of presenting the Virgin to the faithful: the eloquent gesture of the saint dressed in a tunic of camel’s hair unmistakably indicates which figure is the most important, an expedient by which the hierarchical relationships between the figures are made manifest, as the artists could no longer avail themselves of the traditional medieval system whereby the most important figures had larger dimensions. With the reform of the altarpiece, the figures acquire natural proportions between them, and new mechanisms are therefore needed to indicate their relationships. Zanobi, dressed in bishop’s vestments, is caught instead in the act of blessing, and Saint Lucy approaches the scene holding in her left hand her typical iconographic attribute, the saucer with eyes, and in her right hand the palm of martyrdom, held as if it were a quill. John the Baptist and Zanobi are present as the patron saints of Florence, while Lucia is the titular saint of the church that formerly housed the altarpiece, and Francis is another figure linked to this place of worship, since it was here, in 1211, that the saint from Assisi stayed for some time on his first visit to Florence (the church is one of the oldest in the city).

The altarpiece in ancient times also had a predella composed of three panels, now dismembered: the central one with theAnnunciation, now in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, and the two side panels divided so that there were four stories, one for each saint. The left panel features the Stigmata of St. Francis and St. John the Baptist in the Desert and is kept at the National Gallery in Washington, while the right panel was further divided: the left side with the Miracle of St. Zanobi at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge and the right side with the Martyrdom of St. Lucy now at the State Museums in Berlin. The whole was enclosed in a frame that has been lost. The altarpiece was temporarily reunited with its predella in 1992, on the occasion of an exhibition on Piero della Francesca’s training and masters (which, as will be seen at the end, could not fail to take into account Domenico Veneziano’s achievements), curated by Luciano Bellosi and held in the halls of the Uffizi.

Returning to the main panel, this is one of the first fifteenth-century altarpieces in which the figures are credibly distributed in space. This is not an absolute novelty: in this sense, Domenico Veneziano had been preceded by other artists, starting with Beato Angelico and his seminal Annalena Altarpiece, which is about ten years earlier and can be considered the first modern altarpiece, and then continuing with Filippo Lippi’s Pala Barbadori, which embraced Beato Angelico’s idea of arranging the figures within a unified space but also managed to go further, eliminating the architectural wings that, in the Annalena Altarpiece, suggested the memory of the division of medieval polyptychs. Domenico Veneziano participates in the new temperament with another innovative work, arranging the figures within a unified space in terms of both perspective study andlighting. The Venetian artist thus imagines an architectural structure similar to a loggia: slender white columns, surmounted by gilded Ionic capitals, support elegant ogival arches, beyond which we see a refined exedra with niches decorated with shells. In front of the central one takes its place the throne of the Virgin, which we do not see because she occupies it with her whole body (we see only the arms, hidden by a silk blanket, but we perceive its shape). Beyond the exedra here appears an orange grove filled with fruit, recalling the medieval theme of thehortus conclusus, which is also symbolic of Mary’s virginity, since it takes up an image from the Song of Songs(hortus conclusus soror mea, sponsa, hortus conclusus, fons signatus, “a closed garden you are, my sister, bride, a closed garden, a sealed fountain”). The tones of the architecture are subdued, set to the chords between shades of pink (echoing the color of the Virgin’s dress, cinched at the waist by a sober belt and covered by the typical blue cloak) and green, and made even more delicate by the skillful diffused lighting coming from the upper right corner, a real, morning light with a clearly definable source, as can be seen from the shadows of the saints on the floor and even more so from those of the architecture: the entire left side is in fact in light while the right side is in half-light, and we note well the shadow marking behind the figure of the Virgin.

For all these reasons Domenico Veneziano’s researches, Carlo Bertelli wrote, “are absolutely consistent with contemporary modern trends, recognizable in the solemn monumentality, in the careful expressive and gestural research, in the disposition in the unified space in perspective scanning,” in the ability of the figures to be, “like the architecture, load-bearing elements of the composition.” The luminosity with which the artist invests the space that “makes the clear, terse hues of the architecture vibrate, defining figures and volumes,” and the rationality of his perspective layout, “which leaves nothing to chance,” are the most interesting novelties of the Magnoli Altarpiece: and it is precisely the rigorous application of perspective, evident especially in the meticulous marble inlays of the floor, which in turn succeeded in making a small revolution, as Chastel had written, that suggests that Domenico Veneziano studied not in his native Venice, but in Florence, where artists had already been working for some years to apply the new science to their works. The arista, moreover, left his signature on the work: we note it on the first step of the throne (“Opus Dominici de Venetiis Hoc / Mater Dei Miserere Mei / Datum Est,” “This work is by Domenico Veneziano / Mother of God have mercy on me”).

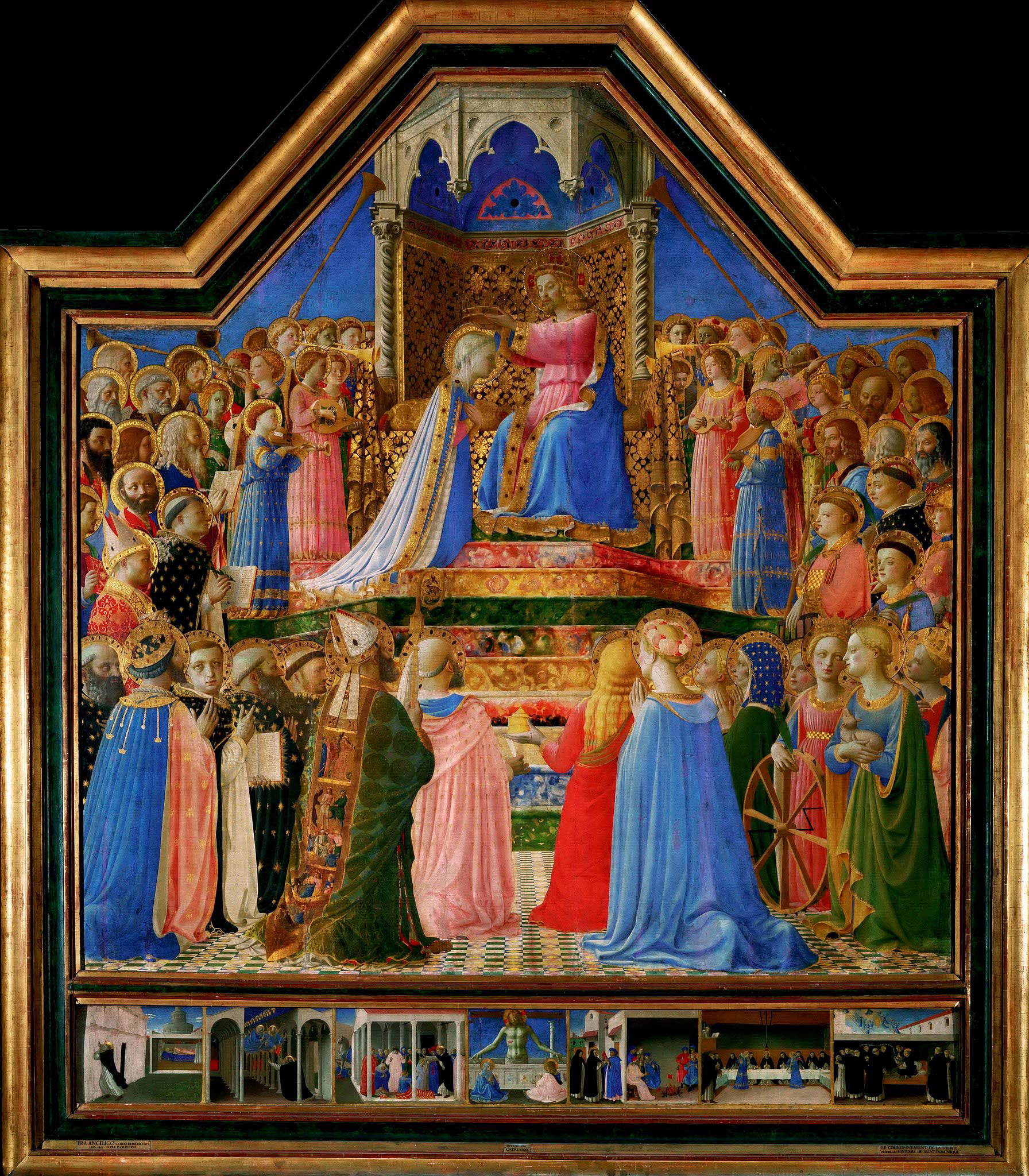

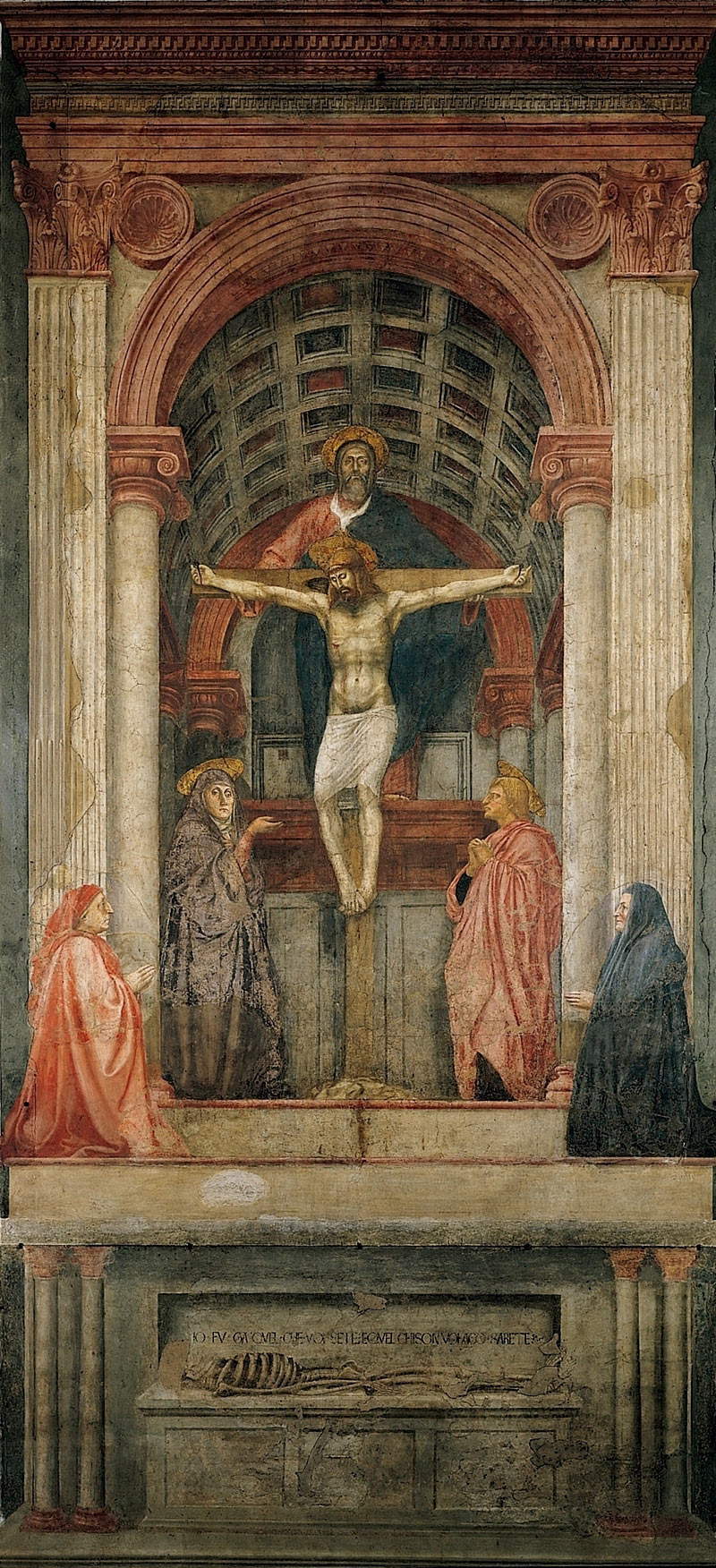

The Magnoli Altarpiece has always been praised by critics, who since the nineteenth century have considered it one of the most interesting works of his season, also acknowledging Domenico Veneziano’s debts, particularly to Beato Angelico for the coloristic setting (but also for the chessboard on the floor, preceded by a few years by theCoronation of the Virgin painted for the convent of San Domenico in Fiesole and now in the Louvre), and to Andrea del Castagno for the connotations of his saints, particularly those more characterized, such as Saint John the Baptist and Saint Zanobi, who have faces with strong, angular, sculptural features like those of the Mugello artist’s characters. In contrast, the profile of Saint Lucia is influenced by the Gothic lines of Lorenzo Ghiberti. Domenico Veneziano’s approach is, at any rate, entirely original. “Here, for the first time,” German art historian Georg Pudelko had to write in one of the first extensive studies of the work, “the figures are in a light-filled space that exists independently of the human figures and acquires its own completely independent artistic value. The means of creating depth are not those of perspective, with the help of which Uccello organized the pictorial space in the same years, but those of light and color. [...] Here space takes priority. It remains a moving fluid, interwoven with light and color. In total contrast to Paolo Uccello, who from the beginning grasped space as an abstract fact, as a form of being, in which almost stereometric body volumes are constructed as tectonic landmarks of depth. And in contrast also to Masaccio’s direction [...] in which space is felt as plastic.” For Luciano Berti, the Magnoli Altarpiece marks “a moment of extreme importance in the history of the Renaissance,” since it “testifies in a perfect synthesis to the new vision of the Florentine Renaissance.” According to the scholar, perhaps the painter came “to a result of such importance precisely because, not being Florentine by birth, he was able to see with a certain detachment the pressing unfolding of artistic events.” Berti, moreover, recognized a precursor role for Masaccio’s Trinity in Santa Maria Novella, as a witness to the “universal dimensions rapidly reached by Florentine Renaissance painting,” against which, however, Domenico Veneziano was able to provide a “more intimate, more personal and at the same time more citizen-like expression of the universal values of the Renaissance.” an intimacy that we find, for example, in the same architecture, similar in every way to that which was being designed in the Florence of the time, and in the same characterized and familiar faces of the saints, “people who could be met on the streets of Florence,” Berti says.

A great art historian such as Ernst Gombrich had compared the figure of Saint Zanobi of the Magnoli Altarpiece, because of the minute description of his clothing (the dalmatic, the mitre) and accessories such as the jewelry and the crosier, to that of the Saint Donazian who appears in a masterpiece of Jan van Eyck’s, namely the Madonna of Canon van der Paele, “an arduous and laborious work both artistically and in terms of content,” as one of the Flemish painter’s leading experts, Till-Holger Borchert, has written in these pages. At first glance, the figure of St. Zanobi might manifest debts to Van Eyck’s St. Donazian (the Madonna van der Paele is from 1436, thus a decade earlier than the Magnoli Altarpiece), since, as Liana Castelfranchi Vegas has well summarized, in the Venetian artist’s saint “every minute reality absorbs that much light capable of exalting form, that is, what Berenson would have said its tactile value.” However, the use of light is profoundly different: in Van Eyck it exalts, it has an almost narrative function. In Domenico Veneziano, on the other hand, it is objective light, functional in defining the real datum. “For the Florentine painters,” Gombrich wrote, “the crisscrossing of furniture, flashing reflections on the surface of things must have appeared as a confused noise, to which they paid no attention in their search for form.” This is not a criticism of Domenico Veneziano: simply, for him, light, while having a primary, fundamental role, was nonetheless part of a larger quest.

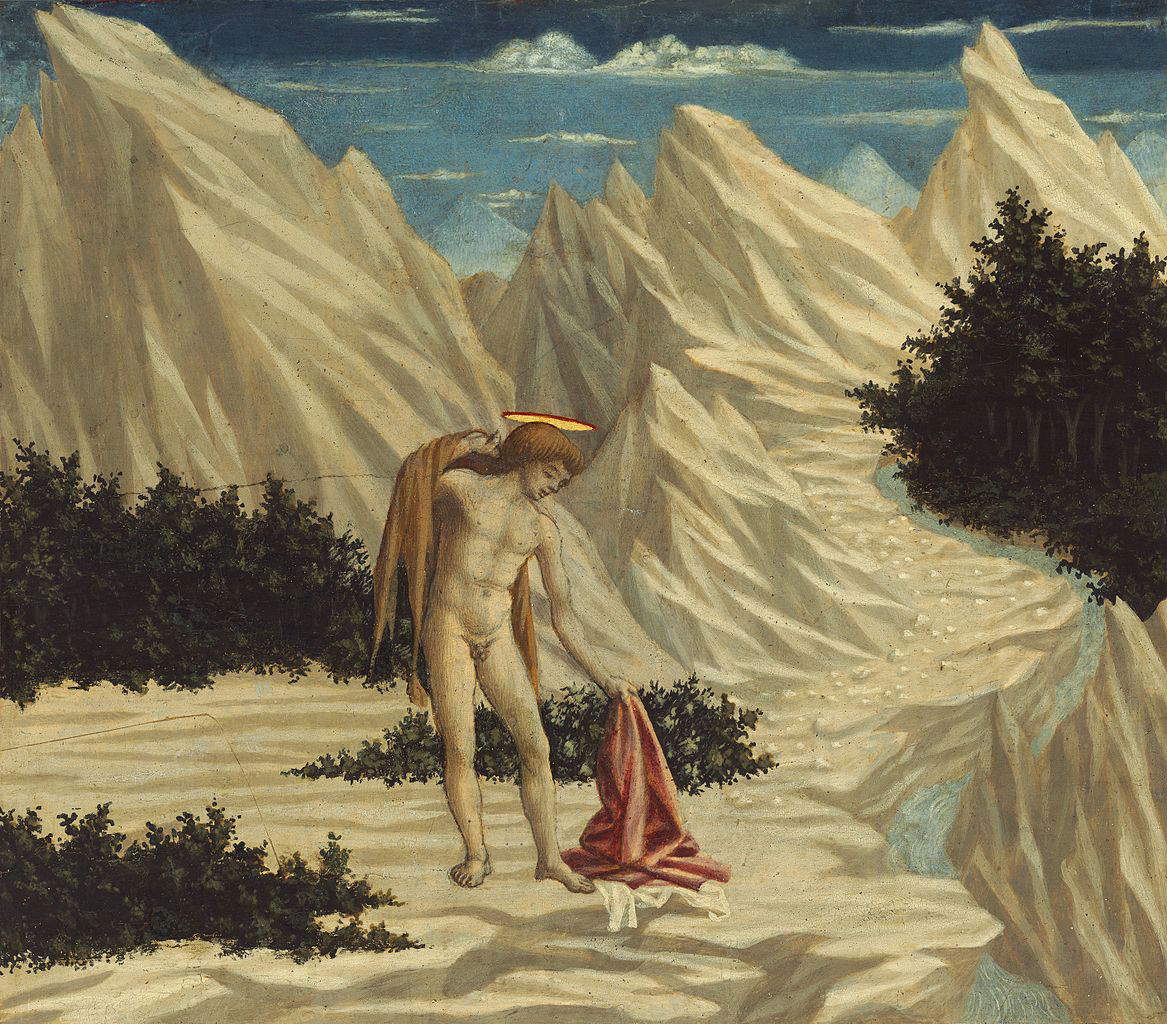

The small anthology on the Magnoli Altarpiece could continue with Giulio Carlo Argan, who, in recognizing (obviously) this painting’s status as “Domenico’s capital work,” recalls how it is a “complex structure of screens that collects and contains natural light in the clear geometric volumes defined by the chromatic tarsias of the architecture,” where natural light “is enough to give the figures a certain dominance over space, an albeit moderate character of monumentality that, in the figure of the Baptist, reveals its origin: Andrea del Castagno.” And again, Mina Bacci could not help but notice how Domenico Veneziano’s architectures recall the traditional compartmentalization of medieval triptychs, although the artist “resolved it, Renaissance-style, into an open and airy loggia.” More recently, in 2021, Edoardo Villata reiterated that in the Magnoli Altarpiece “the effect aroused in the observer is one of monumentality, balance and great freshness at once; qualities that reverberate without detachment from the scenes of the predella.” The predella panels are therefore also worth mentioning, which, while distancing themselves from the solemnity, monumentality and serenity of the main scene, are distinguished by their evident compositional freedom and the lively narrative taste that animates them. One senses an echo of the sacred conversation in the scene of theAnnunciation, which takes place under a bare portico, also foreshortened according to a rigorous perspective and illuminated by a crystalline light, which is distinguished, Bertelli writes again, by its “exemplary clarity, without any yielding to graphic particularisms: the light, through gradations of tone, defines the space with the same rigor as the perspective lines, isolating the protagonists in an atmosphere made up of moods at once domestic and stately.” Beyond the door, moreover, a garden with roses and arbor is observed, remarking an extraordinary attention to detail and also an incursion of everyday life into the sacred scene. In contrast, of a decidedly harsher tenor, still imbued with Gothic atmospheres, is the scene with St. John the Baptist in the desert, set in a landscape of sharp, barren mountains, which are counterbalanced by the sculptural, nude body of the Baptist depicted as he removes his robes to cover himself with the fur tunic he wears in the main scene and which is one of his typical iconographic attributes.

The Magnoli Altarpiece

The Magnoli AltarpieceIn 2019 the Magnoli Altarpiece underwent restoration at theOpificio delle Pietre Dure, completed in 2022, which allowed the work to regain its delicate chromaticism. The colors were blurred as a result of too aggressive cleaning, carried out at the time the altarpiece left the church of Santa Lucia dei Magnoli to enter the Uffizi Gallery: the pictorial film had thus been impoverished, and the colors had lost their brilliance. The altarpiece, in essence, looked decidedly duller than how Domenico Veneziano had imagined (and painted) it. The intervention therefore had the effect of giving the painting its luster again, to the point that at the presentation of the restoration, the superintendent of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Emanuela Daffra, was able to say that although it is a well-known, studied and beloved painting, it is as if it were now being seen for the first time.

This brilliance, this rigorous spatiality, this rationality evidently had to be remembered by Piero della Francesca in the moments when he found himself painting his masterpieces. Following the historical documents that mention him among Domenico Veneziano’s helpers (who was a little older than he was) while he was busy executing the frescoes with the Stories of the Virgin, now lost, for the choir of the church of Sant’Egidio in Florence, we can imagine a young Piero della Francesca, roughly 27 years old, observing the Venetian master at work on his works. And wanting to follow the information rendered by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives, Piero della Francesca was probably also in the master’s retinue in Loreto, having perhaps worked with him as well in Perugia between 1437 and 1438. Vasari reports that Domenico Veneziano died murdered by Andrea del Castagno, who was allegedly envious of his talent and revealed the murder only at the point of death. This is in fact a legend, since Andrea died of the plague four years before his colleague: the Aretine historiographer probably confused the victim of a blood event that actually occurred, a certain painter named Domenico di Matteo, who was attacked and killed in 1443, with Domenico Veneziano, and embroidered around this fact the story of Domenico and Andrea del Castagno being enemies-friends. What is certain, however, is that Domenico Veneziano died in poverty: the records of the convent of Sant’Egidio, where the Venetian painter died, attest that he left nothing behind. We can say, however, that Domenico Veneziano had, at least from an artistic point of view, left a great deal: a legacy that would be picked up by Piero della Francesca, whom we can consider an artist who brought Domenico Veneziano’s insights to fruition, giving rise to a rational, geometric, pure, almost abstract Renaissance, which sees in the Magnoli Altarpiece its first seed. Here, then, is Domenico Veneziano’s true legacy: with him, Florentine art had known light.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.