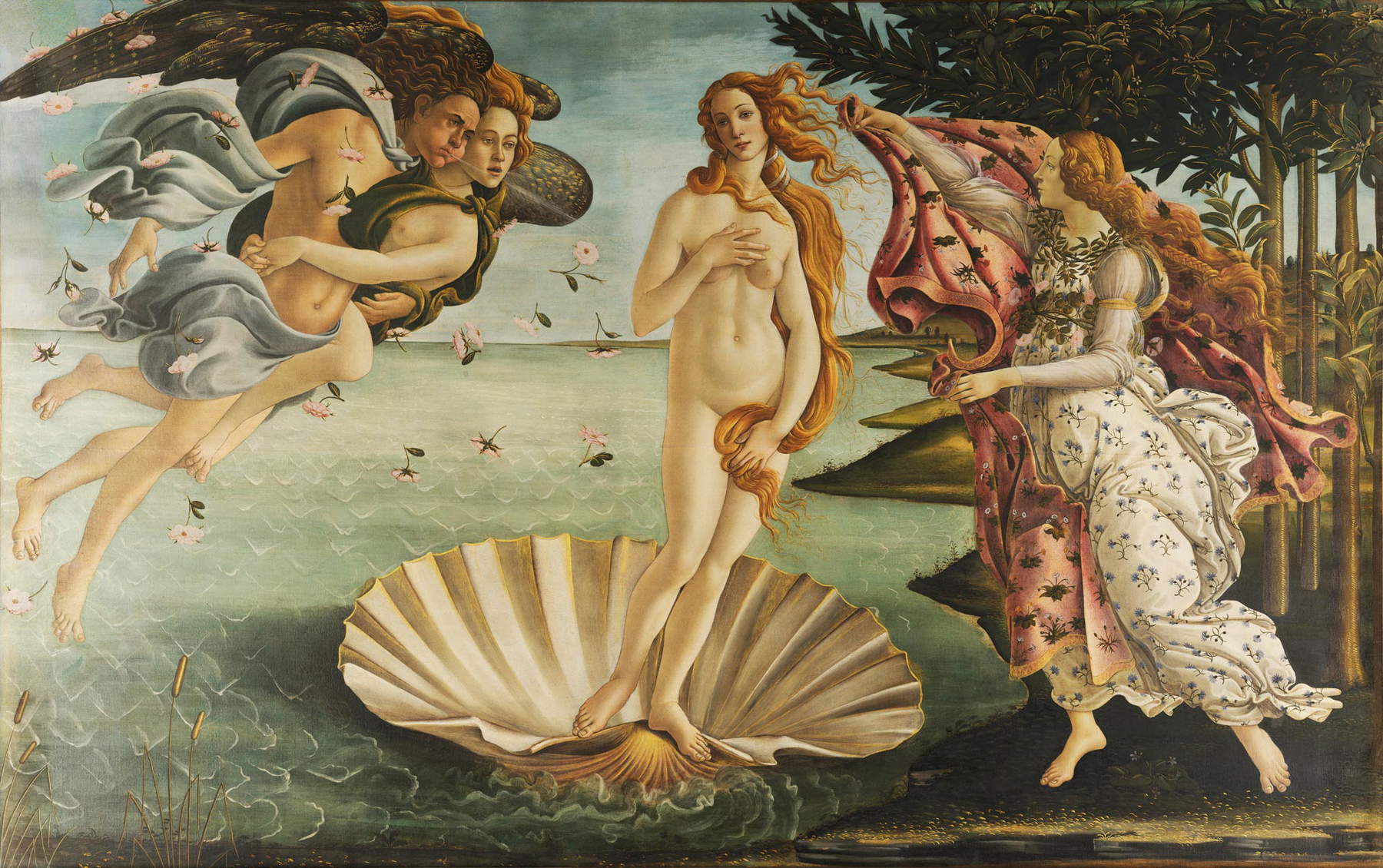

Sandro Botticelli ’s Birth of Venus is a masterpiece for which adjectives have now run out. Celebrated by poets and men of letters, the very image of the Renaissance, the Florentine in particular and the Italian in general, turned into a pop icon and even an advertising image. The meaning of Botticelli’s Venus, however, transcends what we see on the canvas, the marvelous goddess of beauty carried by the shell from which she was born to the shores of Cyprus, the island she cherished, propelled by the winds, with all probbity Zephyrus and Aura, and greeted by a beautiful young woman, perhaps one of the Graces or the Ora personifying spring, the season of Venus. Botticelli’s work is the most vivid embodiment of the idea of beauty according to the artists and thinkers of 15th-century Florence, it is a manifesto of the neo-Platonic culture that produced it, and it is also a work with political overtones since it was commissioned, in all likelihood, by a member of the Medici family, which in fact ruled Florence at the time the painting was made.

However, it is curious to think that for one of the world’s most famous works of art there is no contemporary record. In fact, the first attestation in the sources is to be found in the Torrentine edition of Giorgio Vasari’s Lives, published in 1550, where the work is mentioned along with Botticelli’s other masterpiece now in the Uffizi, the Primavera: “For the city in several houses he made roundels by his own hand and much naked females, of which today still in Castello, the place of Duke Cosimo outside Fiorenza, are two figured pictures, the one Venus being born, and those auras and winds that make her come to earth with loves, and so another Venus that the Graces bloom her, dinotating the Spring; which by him with grace are seen expressed.” The Medici Villa di Castello, the one Vasari refers to, at the time Botticelli was in business was owned by a cadet branch of the family (the one known as the “Popolano,” descended from Lorenzo il Vecchio, brother of Cosimo il Vecchio, the first de facto lord of Florence) and in particular was the residence of the brothers Giovanni and Lorenzo de’ Medici, sons of Pierfrancesco and grandsons of Lorenzo il Vecchio. It is likely that the commissioner was Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco himself, in whose house on Via Larga (now Via Cavour) the Primavera was located in the late fifteenth century. The Birth of Venus is not recorded in the inventories of the Villa di Castello compiled in 1498, 1503 and 1516, which is why it is certain that the work was not made for that residence: it was moved there before Vasari saw it, but we do not know when exactly, nor for what reasons, nor whose decision it was. Only in 1598 would it be catalogued for the first time in the villa’s inventories.

Nor do we know for sure who might have suggested the theme of the painting to Botticelli, but given the relationships that ran at the Medici court the most plausible hypothesis is that the iconographic program is to be attributed to the poet Agnolo Poliziano, the author, after 1478, of a poem in octaves entitled Stanze per la giostra del magnifico Giuliano di Pietro de’ Medici, and written to celebrate the victory in a tournament (held on January 29, 1475, in Piazza Santa Croce in Florence) of Giuliano de’ Medici, younger brother of Lorenzo the Magnificent, who had organized the joust instead. In the poem, Poliziano described a love affair between Giuliano de’ Medici and the young noblewoman Simonetta Vespucci: in one of the scenes, Cupid, after having made the two fall in love, returns to the palace of his mother Venus in Cyprus, where the poet describes some reliefs depicting precisely the birth of the goddess (“In the stormy Aegean in Teti’s lap / One sees the genital shaft welcomed / Under different volger of planets / Errar per l’wave in white foam wrapped; / And within born in vague and glad acts / A maiden not with human countenance, / By lascivious zephyrs driven to the shore / Turning over a niche, and it seems that heaven enjoys it. // True the foam and true the sea you’d say, / And true the niche and true blowing of winds: / You’d see the goddess in the eyes dazzling, / And the sky laughing around her and the elements: / The Hours pressing the arena in white robes; / The Aura ruffling her and her hair stretched out and slow: / Not one but different to be their face, / As it seems to sisters well suited. // You could swear that from the waves came forth / The goddess pressing her mane with the right, / With the other the sweet apple she covered; / And printed by the sacred and divine foot, / Of grasses and flowers the rena clothed herself; / Then with happy and peregrine semblance / By the three nymphs in her lap she was received, / And with starry garment wrapped”). It has been speculated that Simonetta Vespucci herself was Botticelli’s muse(a myth largely debunked), while it is decidedly more likely that the image draws inspiration, at least in part, from Poliziano’s verses.

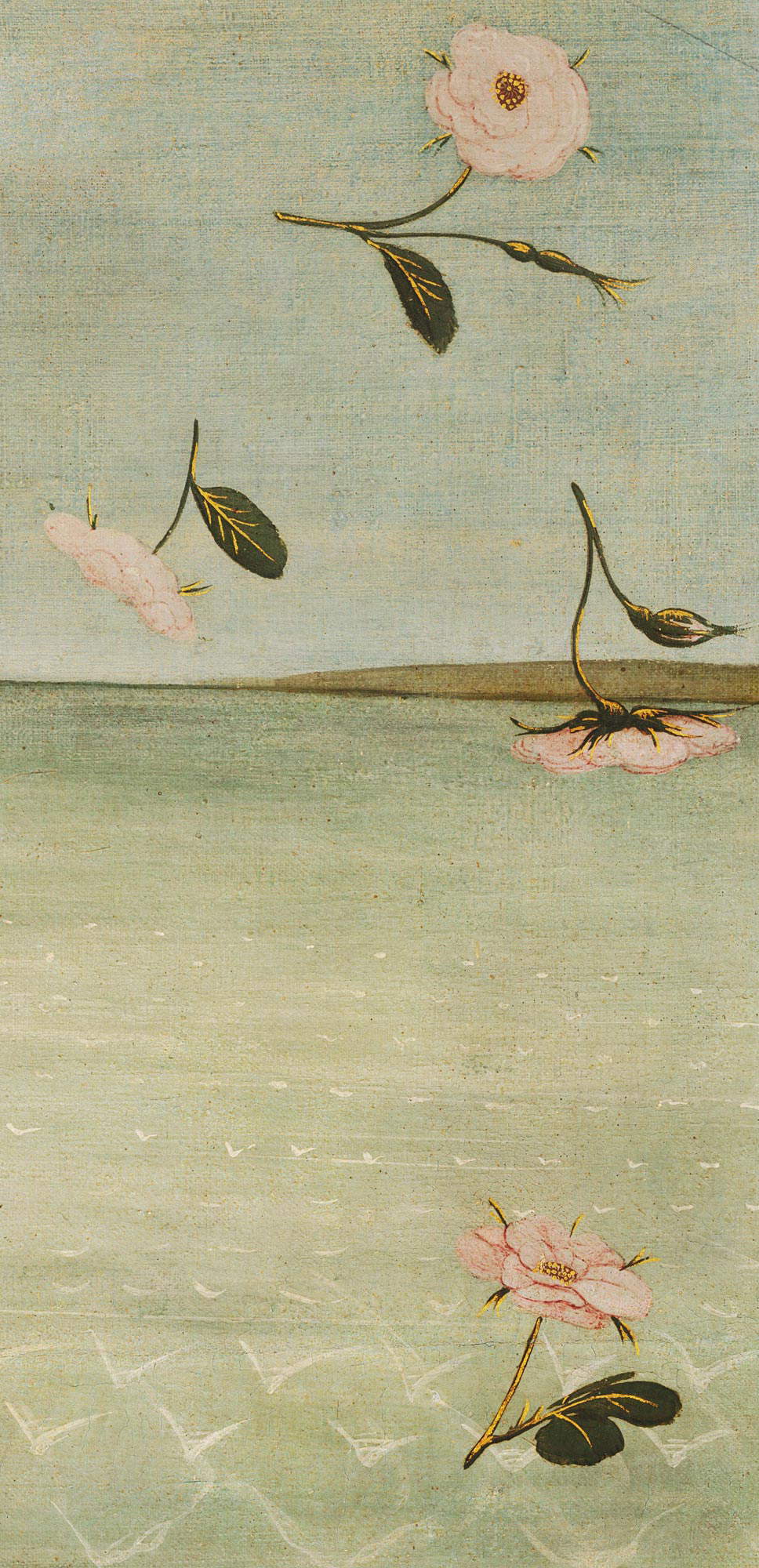

The work, indeed, finds timely correspondence in the octaves of the Joust. Venus, nude, caught holding her long blond hair with one hand covering her pubis while holding her breasts with the other, is at the center of the composition, above a “niche” (a shell) plying the Aegean Sea amid frothy waves, “pushed to the shore” by the “zephyrs,” i.e. by the winds, which we see on the left, caught in mid-air, graceful, with wings spread, dressed in light cloths of iridescent blue silk, in the act of blowing from their mouths to bring the goddess ashore, where a jagged coastline awaits her, with the elements of the landscape reduced to a minimum (only a few trees are seen here and there). This is not in fact an image of the birth of the goddess in the strict sense, as the title by which it is universally known suggests (and which dates back to the 19th century, when it was thought that the artist actually wanted to paint the moment of the goddess’ generation): Botticelli depicts the next moment, that of the arrival on the island of Cyprus. Poliziano’s repertoire was not his own invention: in fact, the description of Venus’ arrival in Cyprus draws from the classical tradition, beginning with one of Homer’s two known hymns to Aphrodite, first printed in 1488 in Florence by the Greek humanist Demetrios Chalcondylis (in Ettore Romagnoli’s translation: “The venerable, the beautiful with the golden wreath, Aphrodite / I will sing, who all the peaks of marine Cyprus / protects, where the fury of Zephyrus who moistly breathes / transported her, on the waves of the sea that eternal resounds, / over the soft froth”) and from Hesiod ’s Theogony (again in Romagnoli’s translation: “And the shames, just as before he severed them with iron, / From the continent away he hurled them into the rolling sea. / So for a long time in the pelagus they wandered; and around / the immortal flesh rose white foam; and nourished / a maiden was of it, who first to the most holy came / men of Cythera. From Cyprus thence to the island she came. / And here from the sea came forth the venerable Goddess, the beautiful one; / and grass under her soft feet grew; and Aphrodite / the gods call her, men call her: that she / was from the froth nourished.”). Botticelli’s Venus, however, shows some obvious differences from Poliziano’s text: in fact, waiting for her on the shore are not three nymphs but a single woman, the silk mantle in which she is about to be wrapped is decorated with flowers and is not starry, and the wind that propels her carries with it a whirlwind of pink flowers.

The flowers and plants we observe throughout the painting are related to the goddess of beauty; they can also be found in part in Spring and can be easily identified. The flowers carried by the wind are none other than roses: according to myth, in fact, they would have appeared on Earth together with the goddess, led precisely by the spring wind. The maiden waiting for Venus on the shore (as mentioned perhaps one of the Hours, personifications of the seasons according to Greek mythology: we would be dealing, of course, with that of spring) has a dress woven of cornflowers, a flower symbolic of love, linked to marriage. On her chest, the same young woman wears a garland of myrtle, the sacred plant of the goddess. On the meadow beneath the feet of the Ora, blue anemones, a flower linked to the fleetingness of love, since its life is short, are noted. On the silk mantle with which the Ora is about to cover Venus we see the daisy, a symbol of love, and then more primroses of the species Primula elatior (greater primrose, a typical spring flower), and what appear to be cuckoo flowers, other typically spring flowers that bloom in May. The large tree we see behind the Ora is an orange tree: it is the Medici family plant, because of the name by which oranges were known at the time(mala medica, or “medicinal apples,” for the beneficial effects already known in antiquity). Below on the left we find some tife, plants typical of marsh environments throughout Italy and found in great abundance in Tuscany as well, which are distinguished by their distinctive cigar-shaped inflorescences (in the past they were used to make mattress stuffing): it has been suggested that the particular shape of the typha refers to the very myth of the birth of Venus, who was born from the sea fertilized by the seed of her father Uranus, leaking from the castrated genitals of his son Cronus.

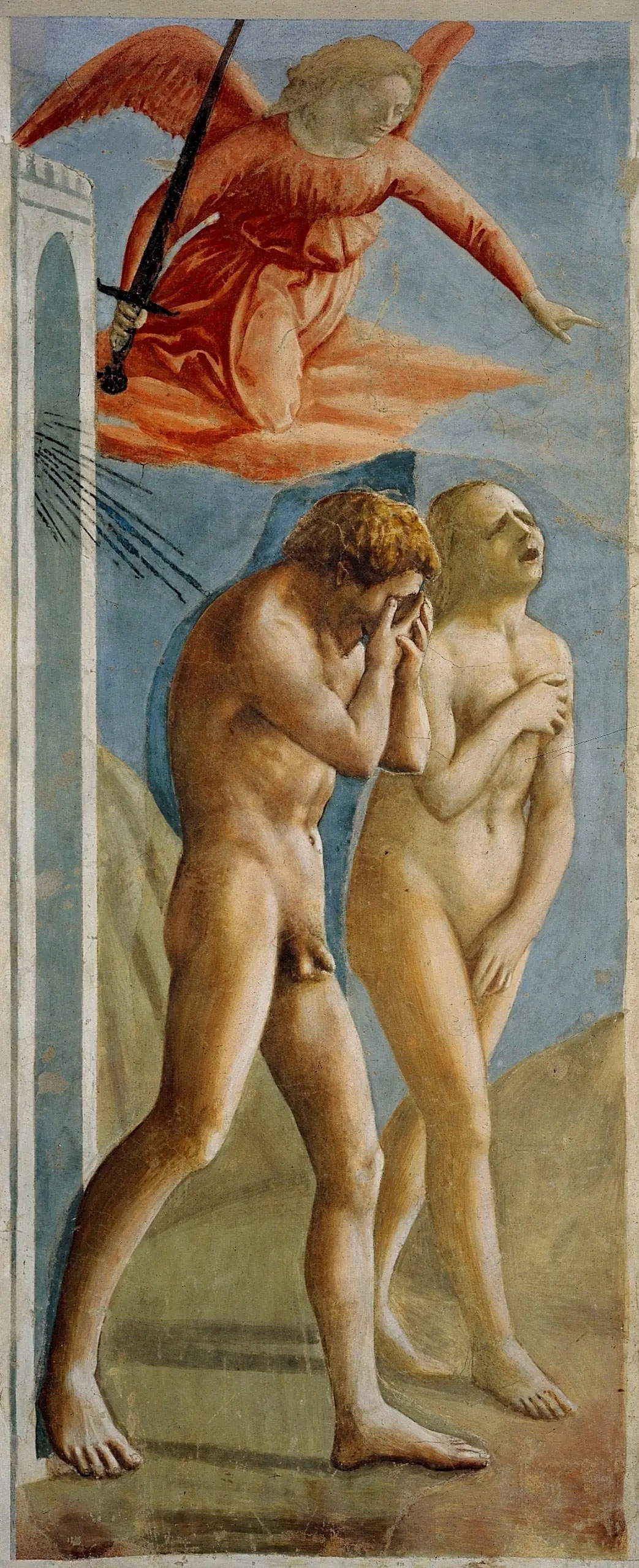

For the figure of the goddess, Botticelli had to look to ancient statues that were kept in the Medici collections. In particular, the hypothesis has been advanced that the artist was inspired by a Venus Anadiòmene (i.e., emerging from the sea) mentioned in 1375 by the scholar Benvenuto Rambaldi, whom we do not know, however. It is, however, to be assumed that the appearance of the sculpture must have been similar to that of the Venus de’ Medici, the masterpiece of Greek Hellenistic sculpture that is said to have come to Florence in 1677 by Grand Duke Cosimo III: the goddess, in the statue signed by Cleomene di Apollodoro, has a pose quite similar to that of Botticelli’s Venus, depicted therefore with the attitude of Venus pudica, so called because she tries to cover herself with her hands after emerging from a bath. We therefore do not know the work that exactly must have been Botticelli’s point of reference, but what is certain is that the type of the Venus p udica was already widely known in Florence and Tuscany, as Masaccio ’s precedents (the Eve of the Expulsion in the Brancacci Chapel) and Giovanni Pisano ’s Prudence, which adorns the pulpit of Pisa Cathedral, attest. On the other hand, with regard to the figures of the two winds on the left (the male character is Zephyrus, the warm west wind that announces spring, while for the female one the identification is more doubtful, but it is likely to be Aura, a deity associated with the breeze), it is entirely plausible that Botticelli was inspired by the personifications of the Etesii winds that appear in the famous Tazza Farnese, the large cameo that is now housed in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples and was in the collection of Lorenzo the Magnificent in Botticelli’s time.

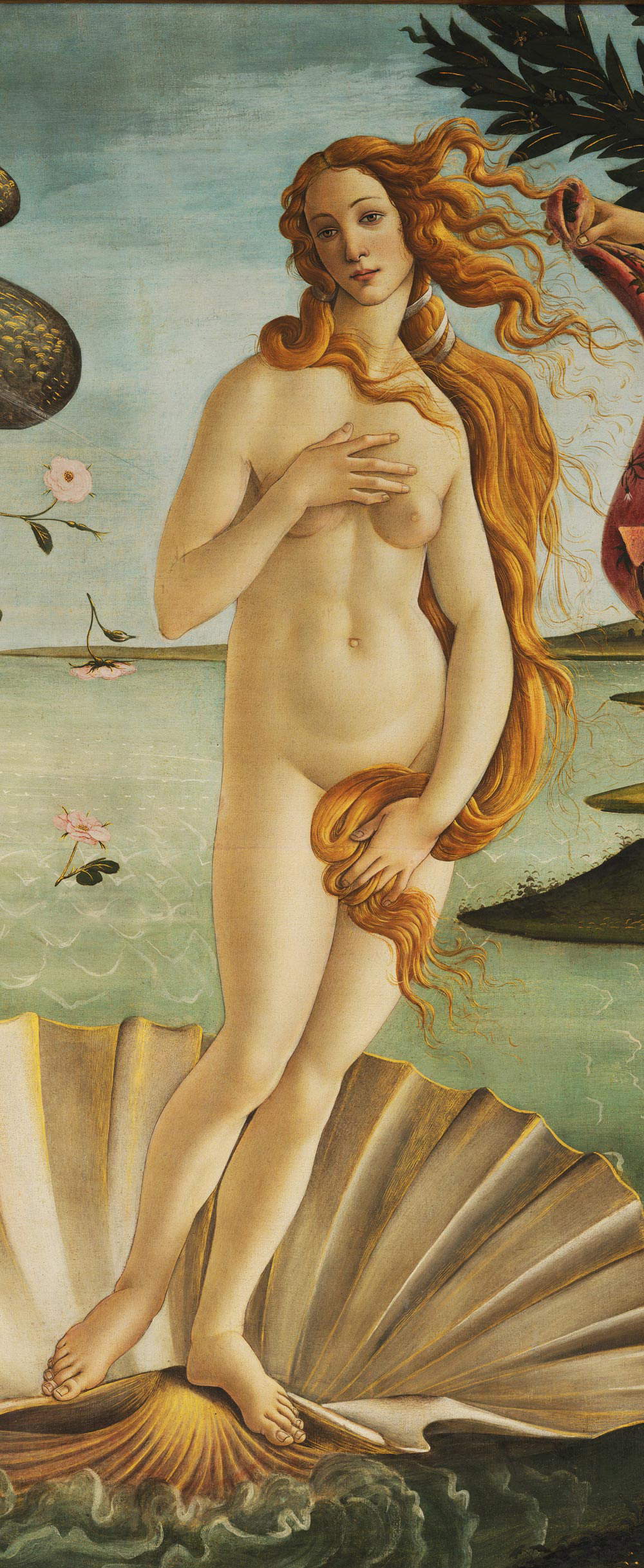

However, the proportions of Botticelli’s goddess are unnatural: “the painter,” wrote scholar Diletta Corsini, “is not concerned here with the correctness of the drawing: Venus’s shoulders are too sloping, her neck unnaturally long, her left forearm bends in an impossible way, and the goddess’s eyes themselves are asymmetrical.” Eyes that, moreover, are presented with larger-than-normal pupils: in the Renaissance, Florentine women in fact used drops of belladonna to make them dilate (it was believed that the gaze in this way acquired more charm). “Yet,” Corsini continues, “the body and face of this Venus were taken as symbols of the Renaissance spirit and beauty. The composition, precisely by virtue of these ’errors’ (or rather, licenses) of the painter, is a miracle of harmony and perfect balance: beauty arises from those slight irregularities that interrupt the too easy symmetry, the predictable correspondences.”

Venus as a symbol of beauty, then: scholars have long wondered about the possible meanings of the painting, however, and most art historians have shown substantial agreement in placing the Birth of Venus within the framework of Neoplatonic culture. Plato recognized the existence of two Venuses: the Venus Urania, or the celestial Venus, daughter of Uranus, and the Venus Pandémia, the terrestrial Venus, daughter of Jupiter and Dionea. The first inspired human beings with love understood as affection, as intellectual feeling, while the other was responsible for physical love, desire. And again according to Plato, physical beauty was a means to spiritual beauty. The human being is thus caught between two poles: on the one hand the divine, the spiritual, and on the other the material: man’s task is to rise from instinct and materiality to arrive, guided by reason, at contemplation, which is the proper state of divinity. Beauty, according to the Neo-Platonic philosophers of 15th-century Florence, is the way in which love manifests itself in the earthly world. Several scholars have found this very thought in Venus, assigning a precise role to each of the characters, although it is still difficult to come to firm conclusions.

One of the best known readings is the one proposed in 1893 by Aby Warburg, taken up in 1945 by Ernst Gombrich: according to the German scholar, Venus is a symbol of humanitas, that is, a humanity that is a synthesis of all virtues. A few years before the painting’s probable completion, between 1477 and 1478, Marsilio Ficino had written a letter to Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici (then 14 years old), in which he recommended that the young man be inspired precisely by the goddess Venus, whom Ficino saw as an embodiment of the ideal of humanitas, a “nymph of excellent grace born from heaven and more than others loved by the most high,” to use the words the philosopher used in the same letter: “her soul and mind are Love and Charity, her eyes Dignity and Magnificence, her feet Grace and Modesty.” Venus is thus a symbol of humanitas that elevates human beings from the senses to divine contemplation, and her nakedness, in this sense, becomes a symbol of the purity of the soul. According to Erwin Panofsky, the Venus in the painting is an allegory ofspiritual love, just as the Venus that appears in Spring is, on the contrary, an allegory ofearthly love, according to the dualism that went directly back to Plato.

An interpretation formulated by Giulio Carlo Argan in 1962 denies that the painting is a pagan exaltation of female beauty, and identifies the birth of Venus as an allegory of the soul being born from the water of baptism, so the beauty that the painter would like to exalt would only be spiritual beauty, and not physical beauty: “the nakedness of Venus,” Argan wrote, “signifies simplicity, purity, lack of ornaments; nature is expressed in its elements (air, water, earth); the sea rippled by the breeze [...] is a blue-green surface on which the waves are schematized in signs all the same; symbolic is also the shell.” Edgar Wind, on the other hand, interprets the Birth of Venus as a union of opposites, with passion and sensuality represented by the pair of the two winds, and chastity represented instead by Venus and the Hour that hastens to cover her. It has then been proposed that the Venus may have been a work intended to celebrate a birth, that of Maria Margherita de’ Medici, daughter of Piero Tolosino de’ Medici (an exponent of a secondary branch of the family), who came into the world in 1484. Among more recent readings it is worth mentioning that of Cristina Acidini Luchinat, who in 2001 attributed an exquisitely political meaning to the painting: according to this reading, the coast on which Venus lands would be that of Tuscany, a region identified by the presence of the orange tree, the Medici tree. We would thus find ourselves before a “modernly adapted version of that myth,” according to the scholar, who calls into question a fresco in the summer quarter of the Pitti Palace painted in the 1730s by Cecco Bravo, where Apollo and the muses are depicted as they, driven out of Parnassus, take refuge in Tuscany welcomed by Lorenzo the Magnificent, to show that in his opinion certain cross-overs, we would say today, historical-mythological were part of the cultural codes of the Medici court (even if one hundred and fifty years still pass between the Birth of Venus and Cecco Bravo’s fresco, but according to Acidini such a lapse of time is not sufficient in any case for her proposal to be considered implausible). An interesting hypothesis, but perhaps more fitting for a large decorative apparatus intended for the hall of a palace than for a painting that probably had a precise recipient and was placed in his private rooms. The work could, however, have implicitly had political significance: Venus-humanitas, for example, could easily have risen as an ideal guide for a man destined for public office. Pierfrancesco de’ Medici’s Lorenzo himself, the one most likely to have commissioned the Venus, worked in diplomacy and administration in the Medici state.

The knot over the possible commissioner is further complicated by the fact that the Birth of Venus was done on linen canvas rather than on panel (the Primavera was painted in tempera grassa on panel instead), an unusual medium for Botticelli and for 15th-century Florentine painting in general, since it was the panel that was most widely used: it cannot be ruled out that the two paintings, made in the same turn of the year, were also intended for two different patrons, and were intended for two different settings. On the canvas, before executing the painting, the artist gave it a mestica, that is, a mixture of pigments that was used to prepare the painting itself: another peculiarity consists in the fact that Botticelli decided not to spread, on the mestica, the typical white imprimitura (a preparation usually based on glue and chalk that is used to prepare the support and to give resistance to the painting), opting instead for a preparation based on blue chalk to give the painting the bluish tone that distinguishes it. By avoiding laying down the white primer, Botticelli wanted to ensure that the colors would eventually turn out lighter and brighter. The technique that the painter used was that of so-called “lean” tempera, that is, with a base of animal and vegetable glues: in this way Sandro Botticelli wanted to give greater luminosity to the painting and produce a fresco-like effect.

And indeed, the Birth of Venus appears to us to be a crystal-clear painting, with clear, terse tones, with Venus’ slender, snow-white body standing out also through the use of the soft but sharp outline that is perhaps the most recognizable of Botticelli’s painting (the artist used it to accentuate the grace of his figures), and whose windswept hair perhaps retains an echo of Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise De pictura, and in particular the passage in which the great architect and theorist prescribed ways to make a hair wavy and flowing. As we read in the vernacular version, “Now, then, since still the non-animated things move in all those ways such as we said above, therefore and of these we will say. They delight in hair, in manes, in branches, fronds and garments to see some movement. How certainly I like in the hair to see which I said seven movements: they turn in one turn almost wanting to anode, and sway in the air similar to flames; part almost like snakes weave among others, part growing here and part there.” The movement of the hair is produced by the winds blowing from left to right: this is the image we see on Botticelli’s canvas today. However, in an early redaction, as has been revealed by diagnostic investigations, Botticelli “had conceived,” wrote restorer Ezio Buzzegoli, “the scene with Venus being carried over the sea by a slow forward movement toward the viewer, while the Winds and the Hour participate in the unfolding of the action almost as bystanders.” The hair, in the first drafting of the painting, was not moved by the wind, but framed the head, more or less following the course of the hair of the Venus preserved today in the Galleria Sabauda in Turin, variously attributed to Sandro Botticelli or his workshop. The few swirls served simply to make believable the movement of the shell carried by the waves toward the shore. Why then this modification? Perhaps, Botticelli changed his mind precisely inspired by the words of Leon Battista Alberti: “it really seems,” according to Buzzegoli, “that Botticelli’s willingness, as indeed of the other masters contemporary with him, to take inspiration and suggestions from the literary sphere is confirmed by what the reflectography of this work has brought to light.” Other elements differentiate the final drafting from the original one: the change in the faces of the two winds, which from bystanders become participants, and the mantle that the Ora offers Venus (in the first version it had no collar opening and, lacking the action of the winds, did not flutter to the right but fell vertically to cover the landscape).

Botticelli’s afterthoughts tend to make the scene even more dynamic. But one of the most evident characteristics of Sandro Botticelli’s style, which can be appreciated at its height precisely in the Birth of Venus, is precisely the particular sense of movement that is given first of all by the rhythmic progression of the lines, which almost oppose the solid volumes of the bodies (Venus herself is strong with a statuesque, almost monumental presence), so that movement and stillness coexist even in the same figure. In Botticelli’s rhythmics, Giulio Carlo Argan has written, “the recurring courses of the line tend to subtilize matter, to give it the imponderable substance of light: more precisely, to make itself light and not to receive light. It is through those linear rhythms that the figures reach a perfect, almost theoretical condition of diaphanity; and in fact trace the margins of greater transparency of veils. Indeed, just where the line seems to reach the purest graphic quality, it reveals itself as the ultimate determination of light.” A rhythmic pattern that, according to Argan, had a precise precedent in the reliefs that Agostino di Duccio made for the Malatesta Temple in Rimini.

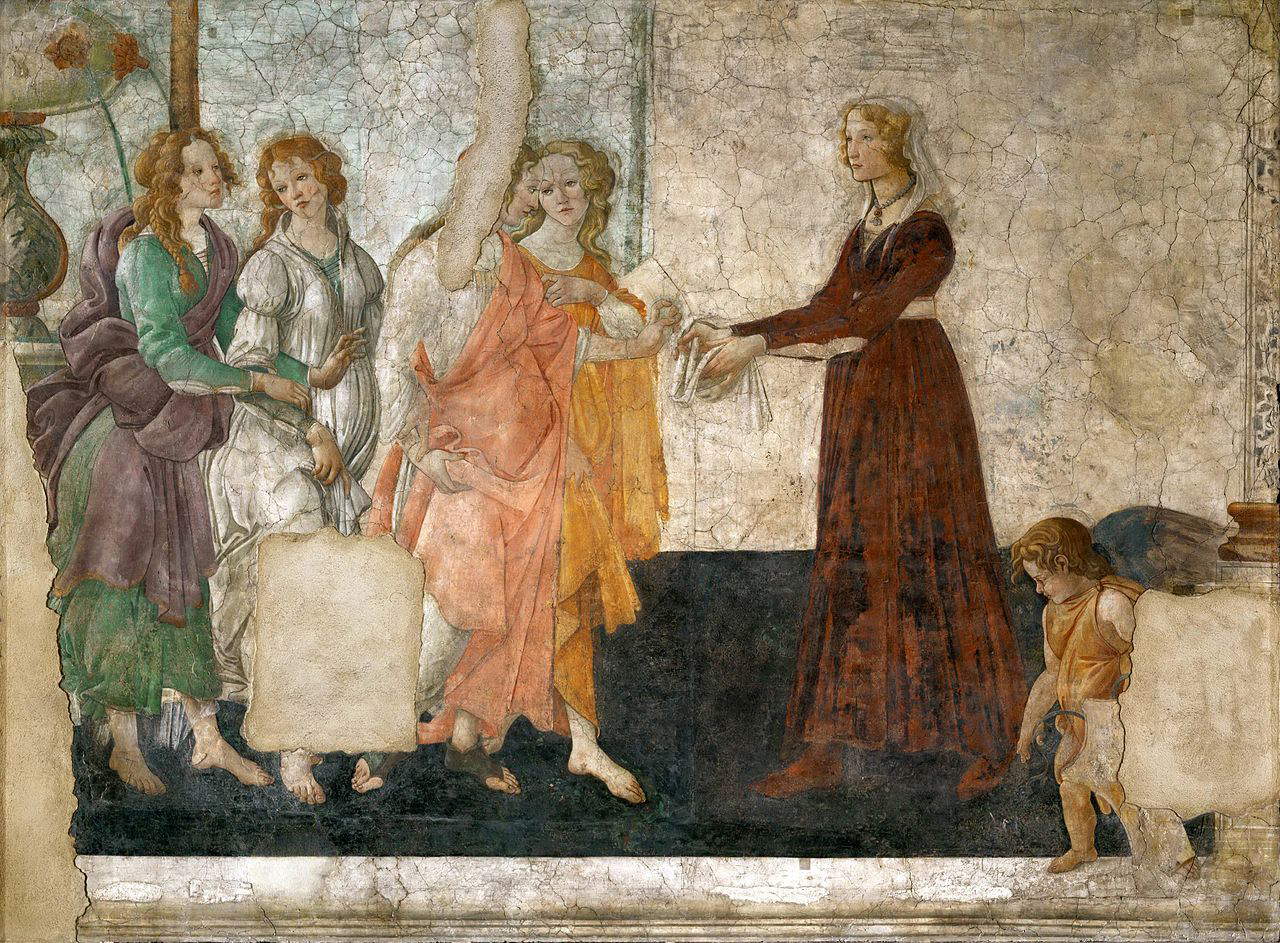

There remains, finally, one last question around the Birth of Venus: its dating, a subject around which the most disparate hypotheses have been formulated. Today there is a tendency to consider it probable that the work was executed around 1485, after Botticelli’s return from Rome, the city to which he had gone to work on the frescoes in the Sistine Chapel (he remained there from 1480 to 1482), and in a period not too distant from that in which the artist executed the frescoes at Villa Lemmi in Fiesole, where another depiction of Venus can be found (we do not know the exact date of the completion of this work, but it is likely that the artist waited there after 1483, or at any rate not later than 1486: the frescoes were later detached, transported on canvas and put on the market in the second half of the 19th century, and since 1882 they have been the property of the Louvre, where they can be seen). It has long been thought that the Birth of Venus was conceived together with the Spring, a possibility that today tends to be ruled out instead: the Birth is smaller in size, appears stylistically later than the Spring, and, as seen above, was done with a completely different technique and in a different medium (the Birth of Venus is the earliest known large canvas work).

These details are certainly not enough to completely rule out the hypothesis that the two paintings were intended for the same person, but what is certain is that about the Birth of Venus, despite being one of the most celebrated and celebrated paintings in the history of art, much remains to be discovered and studied: there are more things we don’t know than things we do know, and it is likely that certain details will continue to elude us for much longer, if not forever.Many have written about the Birth of Venus, grappling with its meaning, interpreting certain details, identifying characters, or trying to reconstruct its history. And many more will write about it: of this we can be sure.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.