“This very strong painter sums up in a vision that is almost always personal, rough and sincere, all the concerns of modern painting.” Thus defining Achille Funi (Ferrara, 1890 - Appiano Gentile, 1972), in 1916, was Umberto Boccioni, who in an article published that year in the weekly Gli avvenimenti praised the flair of the young painter, then only 26 years old, and who had, however, already developed a personal poetics, at that time accomplished, although ready to change direction within a short time. Funi had left the Brera Academy in 1910 and had thus begun six years earlier his own independent path, which in that period would take on the direction of Futurist experimentation. The anthological exhibition that Ferrara dedicated to the painter(Achille Funi. Amaster of the twentieth century between history and myth, curated by Nicoletta Colombo, Serena Redaelli and Chiara Vorrasi, at Palazzo dei Diamanti from October 28, 2023 to February 25, 2024) has the merit of having proposed an extensive reconnaissance on Funi of the “Futurist period,” if we want to call it that, less known than that of the Novecento group, the Funi of Magic Realism, or that of the great frescoes of the 1930s, but certainly no less interesting. Evidence of this is what Boccioni thought about him.

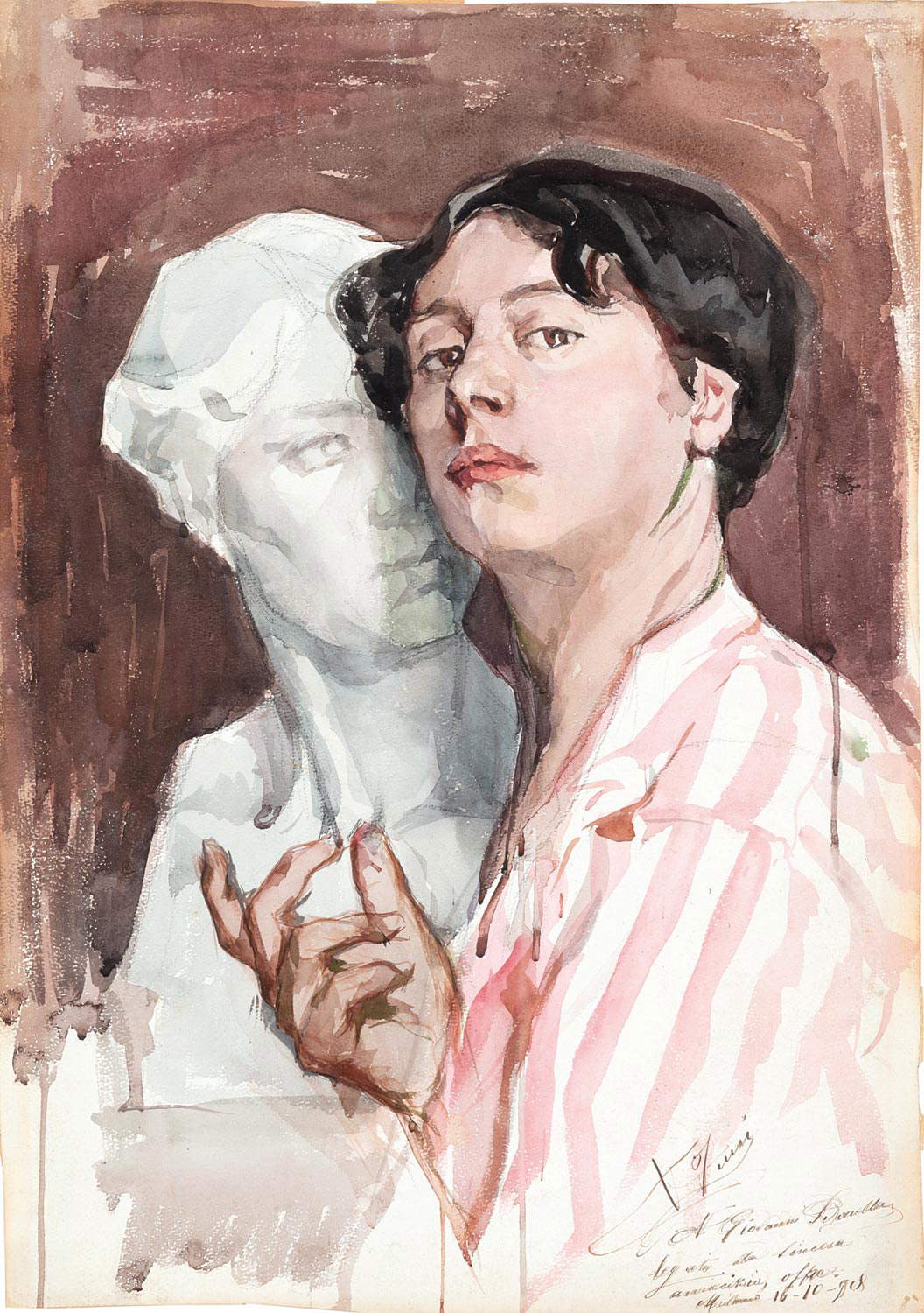

“In his studio,” Boccioni continued in his article, "I saw, Man Getting Off the Tram (Rhythmic Moment), Cyclist (Speed), Two Maidens + tenements + street. In these paintings the schematic synthesis that comes to him from Cézanne and the post-impressionists is freed from the immobility that would make him fall into strange and archaic puppets, a vulgar immobility common to all modern primitivists, who in their search for the firmness of form and the synthesis of the masses return, for intellectual love, to the archaism of all time." Achille Funi, to the vivid memory of the Impressionists, associated the knowledge “of continuity and dynamics.” He was an artist to whom the Academy was narrow and who craved novelty, frequenting the Milan where Marinetti and colleagues had strongly shaken the environment with their bold innovations. At those chronological heights, Funi was essentially an academic artist, albeit a talented one, as the few known youthful works show (for example, theSelf-portrait of 1907 kept at the Mart in Rovereto or the one of the following year, delightful for the naturalness of the pose and the idea of depicting himself together with a sculpture, executed on paper and kept in a private collection). Three years later he is already a completely different artist: this is expected by one of his first works of this period, Corso Monforte, in which the street, buildings, and landscape elements reach a geometric simplification never attempted before (it is not known, however, whether this is Funi’s first non-academic work ever), and merge into a vortex in which one can already sense a need for movement that looks from the outset to the Futurists’ research.

It is necessary to make it clear right away by pointing out that it becomes difficult to speak of a “Futurist Funi” (although the painter, in a 1933 writing, had to declare that “we threw ourselves into futurism on the spot”), since the artist, although he esteemed the work of Boccioni and colleagues, was never part of the group, and his research had few points of tangency with theirs. However, one could speak of a “Funian futurism,” as the Ferrara exhibition does, highlighting the points of tangency but also the divergences that inevitably separate Funi from the Futurists. Meanwhile, Funi, unlike his colleagues who signed the movement’s early manifestos, also seems to be interested in the innovations coming from France, as shown by Corso Monforte himself, for whom the lesson of Cézanne (as well as, though to a lesser extent, that of Fernand Léger) is fundamental. Lacking, in Funi, is an adherence to Marinetti’s Futurism “and its abstracting and deconstructive dynamisms,” writes Nicoletta Colombo, noting how, rejecting even the “firm Cubist monumentalism,” the Ferrara artist “rather realizes pencils and gouaches, many of which entered the Sarfatti collection, in a Cubofuturist style characterized by volumetric contrasts inserted in a rhythmic, plastically deforming movement, praised in 1916 by the constructive revisionism of Boccioni, who admires the fasciature of the forms inferred from the example of Cézanne.” No excess, then, but an experimentalism that sought to overcome the naturalism of nineteenth-century art through a kind of mediation between the novelties that European painting was producing at the time.

Funi, if anything, is to be considered closer to the Nuove Tendenze group, one of the spearheads of the Milanese avant-garde, founded by Leonardo Dudreville in 1913, and which would nevertheless be resolved with a single exhibition (the affair was fully explored in the exhibition that last year the Fondazione Ragghianti in Lucca dedicated precisely to Dudreville). The group took its cue from an exhibition organized that year, that of the “refused” artists of the Caffè Cova, a group of artists who had been rejected by the 1912 Brera Biennial commission. Funi had exhibited there and would exhibit again in 1914 at the first and only exhibition of the Nuove Tendenze group. The group, we read in the program drafted by one of the founders, critic Ugo Nebbia, intended “above all to give a way to affirm itself and come into direct contact with the public to those expressions of art, which, because of their character of advanced research can hardly make themselves known and appreciated in their proper value, in the usual exhibitions.” Nebbia then added, “No determinate formula is imposed: all those who, in their work feel that they have seriously expressed, or attempt to express, a modern and original personal vision, will be well received.” The Novotendenti represented a very heterogeneous group, and they were unable to give themselves an identity or find a common project, even on the aesthetic level: this is also why the operation had a very short duration. However, it is interesting to note that Funi participated in the exhibition with the work that marks his closest point of closeness to Futurism, namelyMan Descending from the Tram, the painting that Boccioni would see in the painter’s studio in 1916.

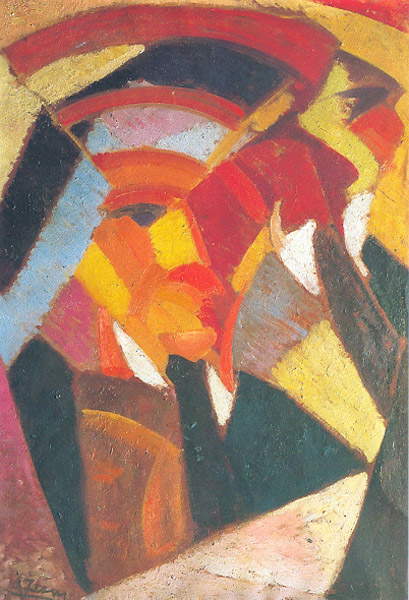

The painting, now housed in the Museo del Novecento in Milan, investigates the figure of a passenger who has just stepped off a streetcar as it moves through space: the means of transportation, which we notice on the right, is almost completely unrecognizable because Funi’s attention is turned precisely to the figure of the man, wrapped in an overcoat, characterized by a sad gaze that looks almost like a mask (Funi was probably thinking of a man returning home tired from work), and depicted within a sort of circle that wraps with a swirling pattern the entire surrounding landscape (a city, with its buildings and lights), to give the impression of movement and speed, just as Funi imagines him thinking of a man walking and seeing everything around him flowing behind him. The impression of movement that Funi gives to his character is such that the man almost seems to fall: no other painting from the “futurist” phase of the Ferrara painter would have gone to these extremes.

Nevertheless, for some time Funi would continue to show himself close to Futurist instances, always observing them, however, from a distance. This was because Funi still remained interested in studying his subjects according to instances of “architectural dynamism of reality” (so Nicoletta Colombo taking up an expression of Boccioni’s), of “movement of the masses that deform on the rhythm of plastic emotions, theorized in 1914 by Boccioni.”) Several works executed by Funi between 1914 and 1915, that is, before the artist’s departure for the front during World War I (the return from the conflict would mark a stylistic turning point for the young Funi), reveal this sensibility. The 1914 Figure in Chromatic Scale is the one that reaches the highest degree of abstraction, and is another work to consider in relation to the Nuove Tendenze exhibition. The artist, in the catalog of the group’s only exhibition, wrote, “I enter the world of forms by eliminating, little by little, all the elements that are not of it.” Consequently, in Figure in Color Scale everything that does not have to do with the “world of forms” is abolished, and the figure in the painting is only shapes and colors, however much we may recognize a human face anyway (if we focus on the painting by looking at it from a general impression, and thus without dwelling on the details, we see the nose, yellow and red; the eye, black; the pointed shape of the chin; the collar of the shirt; the tie). Thus, a work that is not abstract, although indebted to the ideas that were being developed in the New Tendencies group. However, the scholar Elena Pontiggia has noted that “the image is translated not into a chromatic scale (as the title, perhaps apocryphal but now canonical, says), but into a mosaic constructed by dense tesserae of color.” The progression, according to Pontiggia, "may suggest an acquaintance with Delaunay, mediated through Dudreville, who in 1913 had painted a work of only sickles of color juxtaposed and superimposed(Expansion of Lyric). But to Dudreville’s musical linearism, entrusted with pure, luminous colors, Funi contrasts a slow, blocked progression, more polygonal than curvilinear, with a more earthy, calcined chromatic range."

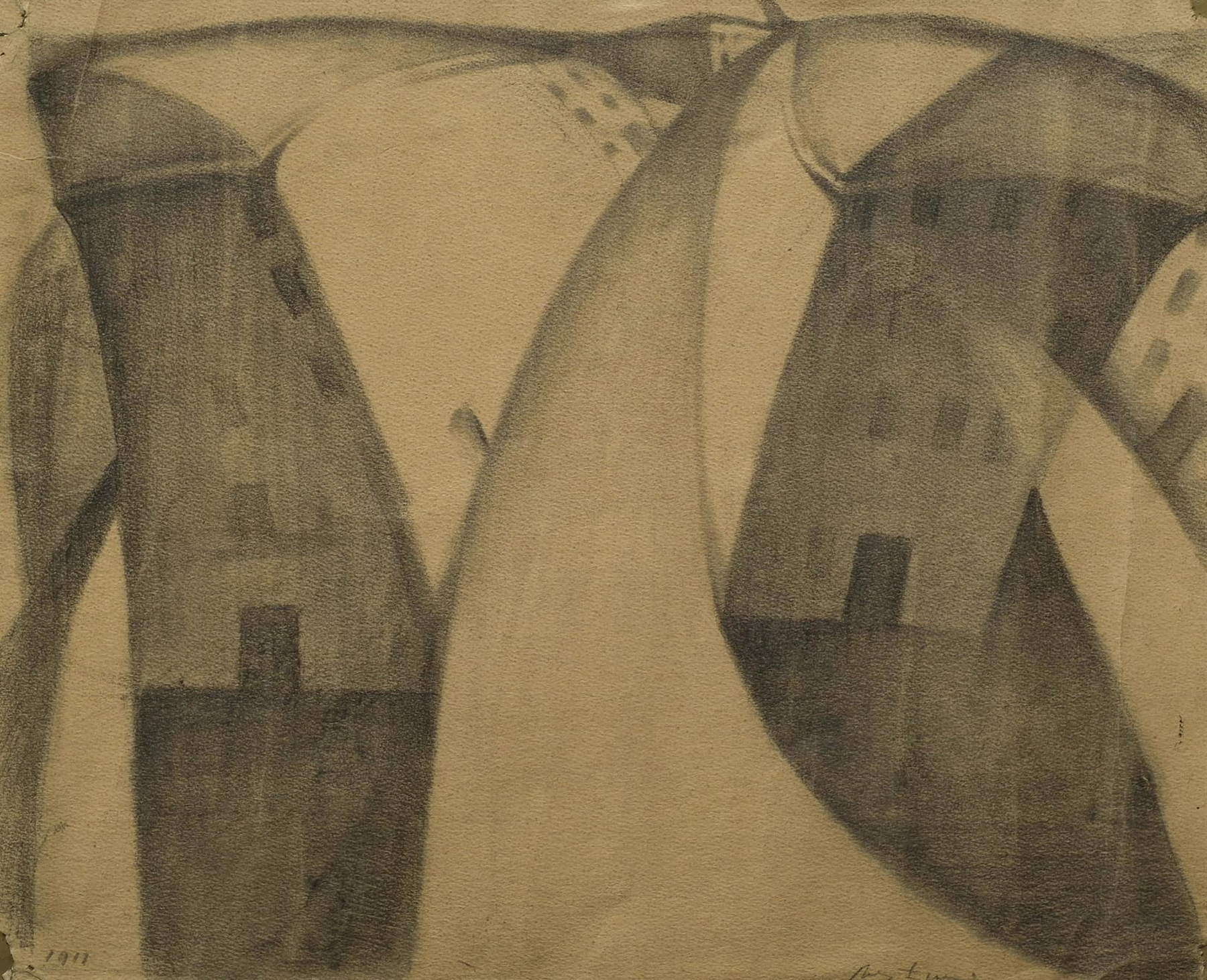

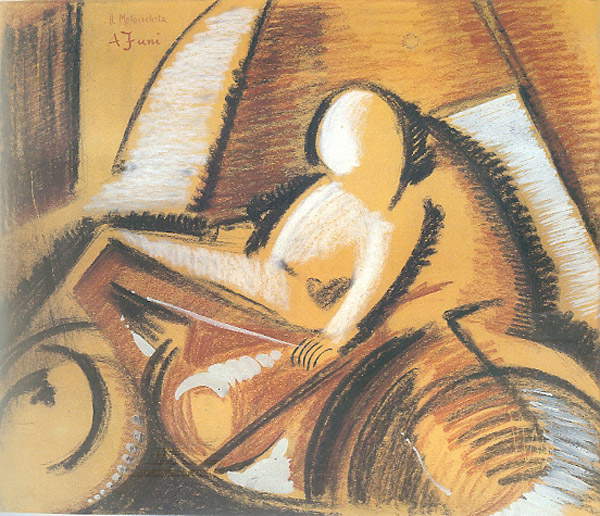

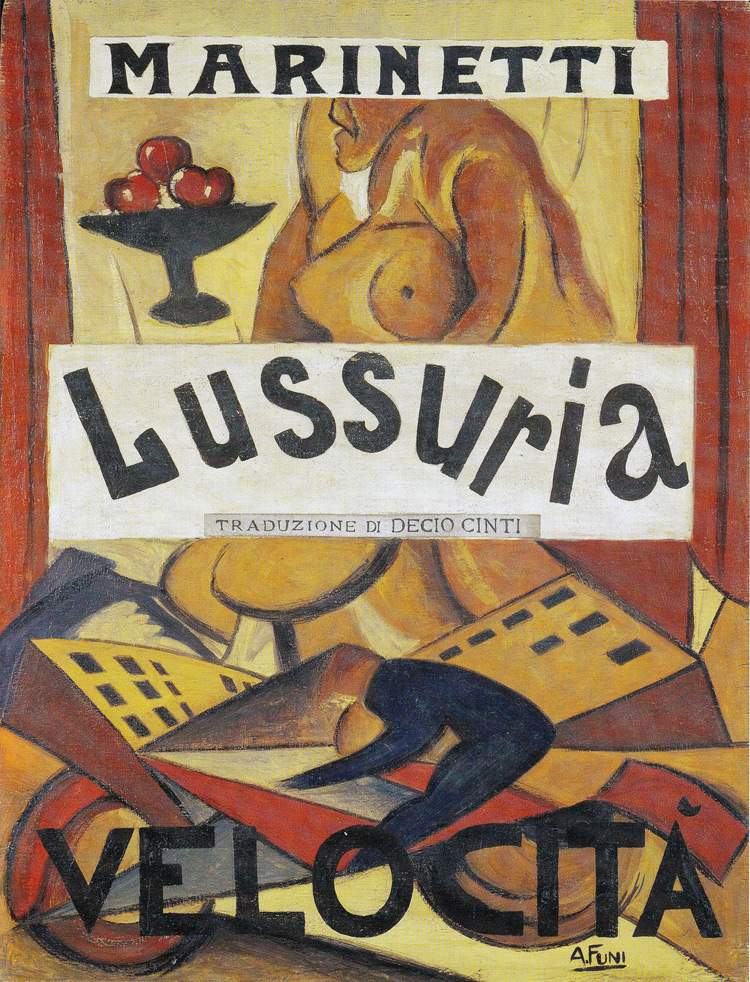

There are also works that highlight Funi’s rapprochement to the themes of dynamism and especially speed, dear to the members of the Futurist cohort. Many of these develop the theme of the motorcyclist, investigated by Funi in several works on paper, on panel and on canvas, and with different variants: one of the best known sees the motorcyclist with his hands on the handlebars of the vehicle and the fairing of the motorcycle stretching forward (so much so that at first glance the motorcyclist almost seems to be sitting...upside down), precisely to give the idea of movement. Another well-known variant is the one that would later end up on the cover of Lust - Speed, a collection of poems and poems by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti published in 1921. In this work (the cover is preceded by a number of proofs on paper and canvas), the motorcycle is caught in its rush through buildings that, as inMan Descending from the Tram, are deformed by the dynamism of the motorcycle. Compared to the earlier Motorcyclist , this second Motorcyclist appears more marked by a linearism that synthesizes figures and landscape elements through geometric forms. The upper part of the 1921 cover, on the other hand, features a female figure embodying the idea of Lust: it is a work executed at a later date, since here Funi already highlights the characteristics of the strong Cézannian experimentalism that would characterize his production upon his return from World War I.

There is also to be pointed out, in conclusion, a Futurist Self -Portrait that Funi executed in 1913: a few years have passed since his first youthful self-portraits, but even to his own image the artist, by then devoid of any ties to the academy, applies the decomposition of forms that distinguishes the works of his “Futurist” period. Indeed: it is some of the earliest evidence of his interest in the avant-garde. Boccioni, in closing his article on Funi, believed that in the face of all this evidence the Ferrara artist had produced works capable of freeing himself “from slavish copying”: “the scene or the effect that strikes the painter is the cue or the key to the plastic construction [...]. We have with this works of a hitherto unknown plastic severity, works freed from all literary or sentimental bondage. When the public realizes this, they will see in Funi one of the best champions of Italian avant-garde painting.”

However, Achille Funi’s avant-garde season, as anticipated, would be very short-lived: already after 1915 his interest in Futurism was exhausted, which Funi abandoned in order to get closer to Cézanne and Cubism. And then, after the war, in the general climate of a return to order, Funi will first be fascinated by dechirican metaphysics, and then go in an even more classical direction: futurism is an experience now definitively archived, as Funi rediscovers the art of the Renaissance, the art of the sixteenth century. Thus was born the Funi of the Novecento group, the one best known to the art public.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.