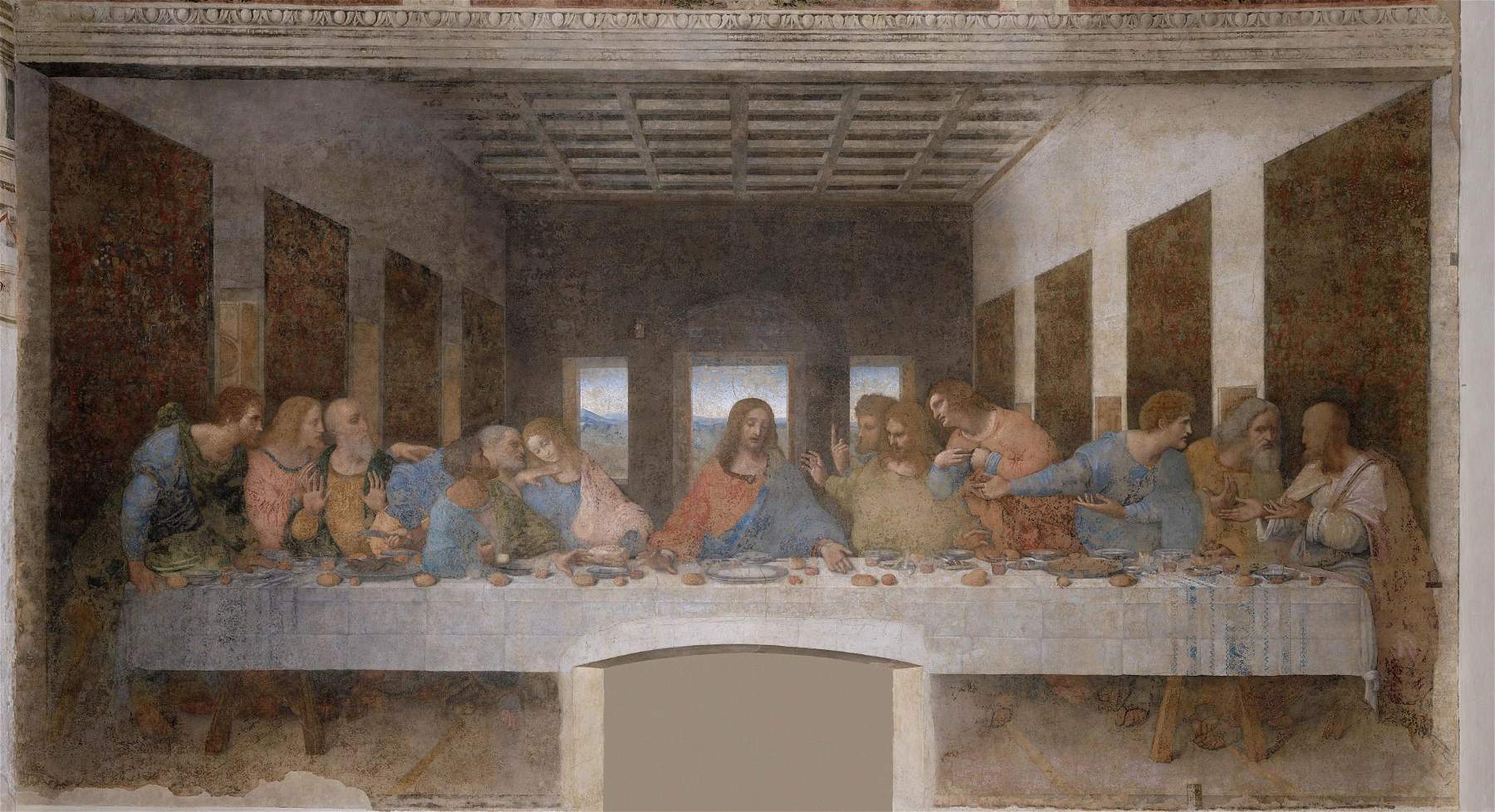

TheLast Supper by Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), the masterpiece that the genius painted on the wall of the refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan, is considered one of the fundamental works of art history because of its extraordinary narrative capacity by which a biblical episode became become a realistic scene, for theoptical illusion with which the artist gave shape to the space by arranging the twelve apostles in small groups frontally to the viewer and making anyone regarding the table see them from an unrealistic point of view, and for being able to make Christ and the apostles express the various motions of the soul by making them anything but static figures. Moreover, unlike the traditional cenacles, the table is not placed near a wall, but in the center of an environment that seems to extend even beyond the figures. Leonardo’s Last Supper was immediately perceived as a groundbreaking masterpiece, which is why copies on canvas began to appear (one is attested to be by Marco d’Oggiono commissioned in 1506 by the dean of the chapter of the French cathedral of Sens, Gabriel Gouffier, now preserved at the Musée National de la Renaissance in Écouen).

A copy in fabric embroidered with precious materials is preserved in the Vatican Museums : a splendid tapestry that was donated on the occasion of an important wedding and that sealed a significant alliance, and then in a short time became the protagonist of one of the most evocative papal ceremonies. Its story was told by Alessandra Rodolfo and Andrea Merlotti, curators of the exhibition All’Ombra di Leonardo. Tapestries and Ceremonies at the Court of the Popes (March 21 to September 3, 2023 at the Reggia di Venaria), of which the aforementioned tapestry ostituisce the main focus thanks to the important collaboration with the Vatican Museums. An exhibition to tell not only the story ofLeonardo’s tapestry, but also the important role of the rites, which spread from France to all the other courts of Europe. In their palaces all Catholic monarchs imitated the ceremonies of the pontiff, and even several sovereigns had tapestries or paintings depicting theLast Supper placed in the rooms where the rite of the Washing of the Feet was held. This was because every year during Holy Week the tapestry was displayed in the Ducal Hall of the Vatican Palace, where in the shadow of the work this solemn rite took place.

But let us see its history in more detail, which the curator delves into in the catalog essay. As already mentioned, the precious tapestry woven in silk and gold was donated on the occasion of a wedding, namely the union between Catherine de’ Medici, niece of Pope Clement VII, and Henry of Valois, second son of King Francis I of France. The work had been donated by King Francis I to the pontiff and had arrived in Rome from France in 1533. The wedding was agreed upon after long negotiations: the pope could thus strengthen the alliance between the Medici and the French crown, limiting the power of Charles V in Italy, who had been responsible for the sack of Rome in 1527, while Francis I could strengthen his power over Italy and counterbalance the power of the Habsburgs. The wedding was celebrated in Marseille and was also attended by the pope, who arrived by sea accompanied by cardinals and prelates; the exchange of rare and precious gifts had then taken place. It is known from the bourgeois Honorat de Valbelle that a few days after the wedding the Great Hall, i.e., the pope’s chapel where mass had been said, was left open to show, in addition to the relics the pope had brought from Rome, the tapestry, which Francis I had wanted to display. “I think this tapestry is the richest and best I have ever seen,” Honorat de Valbelle had commented. “It is woven of gold, silver and fine silk in delicate colors, with characters so well done that they seem alive.”

The tapestry is a faithful reproduction of Leonardo ’s Last Supper (it even has the same measurements) in terms of the composition of the figures of the apostles around the table and the laid table. Even Leonardo’s brushwork, his famous sfumato, is reproduced, thanks to the technique ofachure, which creates shading and renders the flesh tones of the human figures as if they were alive. Even the still lif es on the panel are rendered with very high technical quality, even creating transparencies. But the setting is different from the mural painting in Santa Maria delle Grazie: there is no coffered ceiling and the four large tapestries on each side wall, but architectural wings of Renaissance layout. The arches alternate with decorated pillars; behind the balustrade some buildings can be glimpsed, while behind the arches a landscape can be seen with a castle, buildings, and a stream sloping toward hills and mountains. Above the three arches runs a frieze with winged horses, shells and candelabra, and from the balustrade hangs the crowned coat of arms of the King of France with gold fleurs-de-lis on a blue field surrounded by the collar of the Order of St. Michael.

On the border surrounding the entire scene, however, we notice symbols referring to Francis I and his mother Louise of Savoy: for example, the symbol of wings is linked to her, recalling her maxim, “God gave me wings, I will fly and rest,” while salamanders are linked to the king. In the two lower corners of the border, on the other hand, there is the monogram LOSE, which refers to the figure of Louise, her lineage, that of the Savoy family, that of her husband Charles d’Angoul�?me of the Orleans branch, and the title of Madame d’Épernay and Romorantin. Six uncrowned salamanders in the flames, two in the horizontal borders and a central one in the vertical borders, are found in the main scene, referring explicitly to Francis I, who adopted the symbol from 1504. In the corners of the upper border, on the other hand, there are four Fs and a knot perhaps associated with Francis I’s monogram similar to that on the blade of the sword of François Comte d’Angoul�?me or associated with Claudia of France, Francis I’s wife. The entire decorated band is embellished with knots, the symbol of the House of Savoy but also of Francis I, who had adopted them as a sign of gratitude to Saint Francis of Paola, to whom Luisa had recommended herself to become a mother.

The tapestry is never mentioned, however, before 1533: it is mentioned for the first time in an inventory at the château de Blois, among the fabrics selected to be taken to Marseilles for the wedding. Not much is known about its earlier history: the place of its making remains unknown, although scholars have so far pointed to the Netherlands, an important center of high-quality tapestry production. In his Histoirie sur les choses faictes et advenues en son

temps en toutes les parties du Monde, Paolo Giovio, recounting the exchange of gifts that took place in 1533 between Pope Clement VII and King Francis I, recalls “a very large tapestry, made in Flanders, in which is seen the Last Supper of Christ with the apostles, embroidered with gold on canvas.” And given the quality with which tapestries were made in that area and the passion of the king and his mother Louise for Flemish manufactures, it is very credible.

As for the dating, the presence of the uncrowned salamanders and the hypothesis of the later addition of the royal coat of arms suggested a date before 1515, the year in which François Count d’Angoul�?me, became king. However, the hypothesis was refuted by the recent restoration that revealed a unified weaving without additions in the back of the cloth of the coat of arms, which established that the latter was not woven at a later date but together with the rest of the tapestry. Therefore, the tapestry was made after 1515; also confirming this is the presence of the double cord in the collar of the Order of St. Michael around the coat of arms, which was replaced by Francis I shortly after becoming king to the original"aiguilletes" that connected the shells together, during one of the first meetings of the order in Blois in September 1516.

The work is mentioned again in 1533 in a warrant of payment dated November 28 and made out to Nicolas de Troyes, the king’s silversmith, who received a considerable sum for the purchase of silk and gold and silver cloth for thetapestry’s enrichment: we are probably referring to the red velvet border with gold and silk embroidery and embroidered figures that still appears in somenineteenth-century lithographs but is no longer present today. In summary, the tapestry should have been woven after September 1516, the year of the change in the collar of the Order of St. Michael, and by 1533, perhaps even by 1524, the year of the death of Francis I’s wife, Claudia of Valois, whose initial appears associated with that of her husband in the borders.

A shift in dating that could be significant when one considers that Leonardo da Vinci arrived in Amboise in the fall of 1516 at the French court and, as speculated by Jan Sammer, it is likely that the genius was invited by Francis I to go to Amboise on the occasion of their meeting in Milan in November 1515 when the king went to see the Last Supper. Perhaps the idea of making a tapestry depicting Leonardo’sLast Supper may have arisen on that occasion. And perhaps in France, under the supervision of Leonardo himself, the cartoon of the tapestry was made (the author of the cartoon still remains unknown) on which the subsequent weaving was then accomplished, but this is only a hypothesis. Certainly Francis I was a great admirer of Leonardo, so much so that he called him to his court.

The tapestry in question is among the oldest in the Vatican collections, where it is first recorded in the 1536 inventory, and was often used in court ceremonial. It was displayed in important religious ceremonies, such as Corpus Christi, during which the artifact was placed next to Raphael’s tapestries, or in the ceremonial washing of the feet that took place on Holy Thursday in the Ducal Hall of the Apostolic Palace. On the latter occasion, the pontiff performed the ceremonial in the room entirely decorated with gold-trimmed damasks and the tapestry of theLast Supper that was hung above the stage on which stood the thirteen poor people waiting for the pontiff to imitate the gesture made by Jesus to the apostles.

Because of the frequent use and fragility of the artifact, the tapestry began to deteriorate: it was restored in 1681, as the documents record, and then about a hundred years later, in 1763, until it was decided to have a copy made to be used in its place to preserve it: this was accomplished between 1780 and 1795 on a cartoon by Bernardino Nocchi.

The story of theLast Supper woven in gold and silk thus begins in the sixteenth century, although it is little known; it may have seen Leonardo da Vinci himself, played an important political as well as religious role, but above all it is an extraordinary artifact of the highest artistic quality that the Vatican collections still hold today.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.