In theItaly of the 1950s, the idea of dedicating an entire park to one of the most beloved literary figures for children and adults alike, Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio , was highly original in itself, but opening a park dedicated to Pinocchio and filling it with works by important contemporary artists was something extremely rare: perhaps this reason, too, explains why, since 1956, its opening year, Pinocchio Park in Collodi, opened right at the foot of the home town of the mother of Carlo Lorenzini (Florence, 1826 - 1890), who went down in literary history as Carlo Collodi, has always met with great success. In fact, many well-known names in the art of the time contributed to the creation of the park, which today attracts not only families and fans of the book The Adventures of Pinocchio with which we all grew up, but also connoisseurs of twentieth-century art: Pietro Consagra, Marco Zanuso, Emilio Greco, Venturino Venturi. They all worked for five years, from 1951, the year in which the municipality of Pescia (of which Collodi is a hamlet) announced the competition to have the park built (the 70th anniversary of the publication of the story of Pinocchio fell at the time), to create works inspired by the stories of the most famous puppet ever.

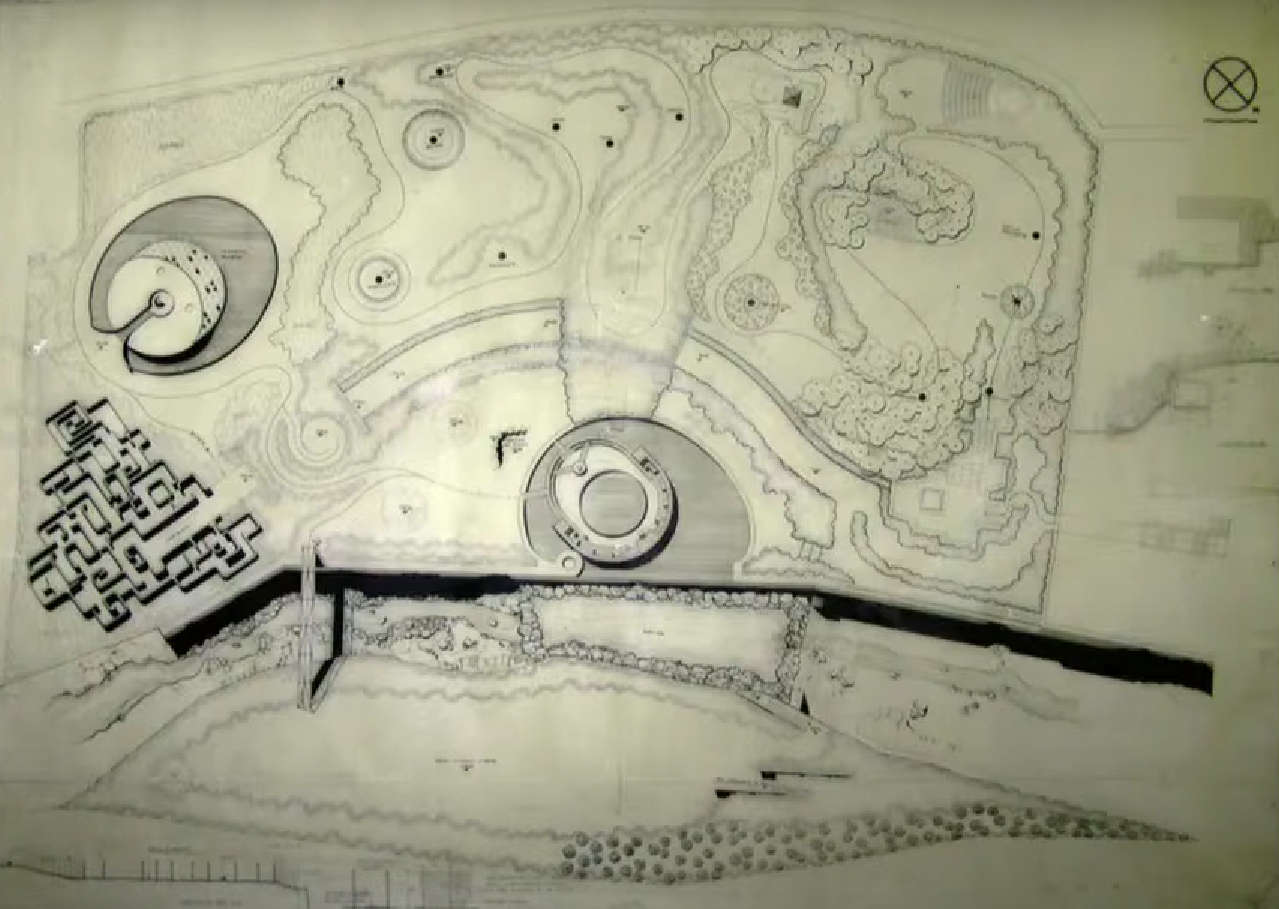

The park did not stay still for long: as early as 1963, in fact, Pietro Porcinai (Fiesole, 1910 - Florence, 1986), probably the only Italian landscape architect of the time to have achieved international fame, was commissioned to design a labyrinth within the park, which was later finished in 1972 after a rather long gestation. It was to symbolize the intricate vicissitudes that Pinocchio is forced to face during the book. Initially, it was to be made of masonry, at least according to the idea of Marco Zanuso , who had provided his directions to Porcinai (who, moreover, had already made some symbolic places in Pinocchio Park, such as the Osteria del gambero rosso and the Teatro dei Burattini) and who was initially to provide the decorations. And it was also to be enriched with water features, sculptures and various insertions. Then, the labyrinth instead took its current form as a vegetated maze, with stone paving (instead of concrete as originally planned). The paving stones, in particular, are the original ones from the surrounding villages, which were replacing them with asphalt: the stones, left in the deposits of the Municipality of Pescia, were purchased by the Collodi Foundation, which used them for the park (they were, however, later replaced with concrete slabs).

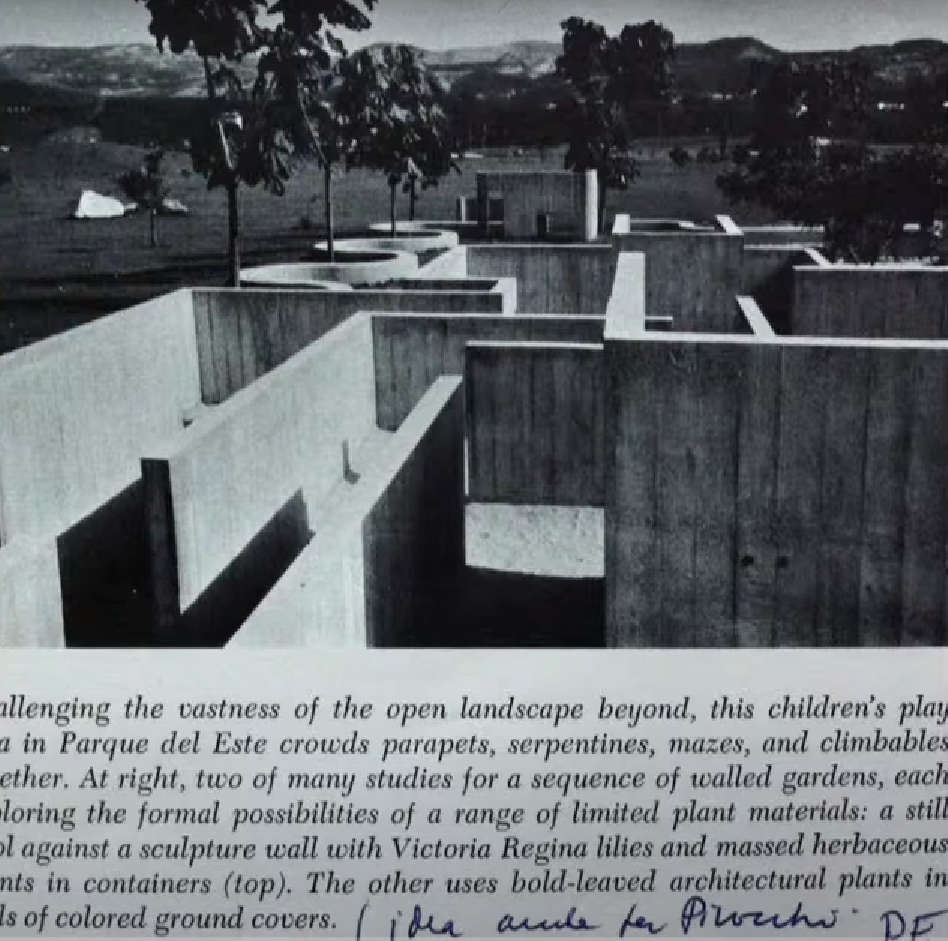

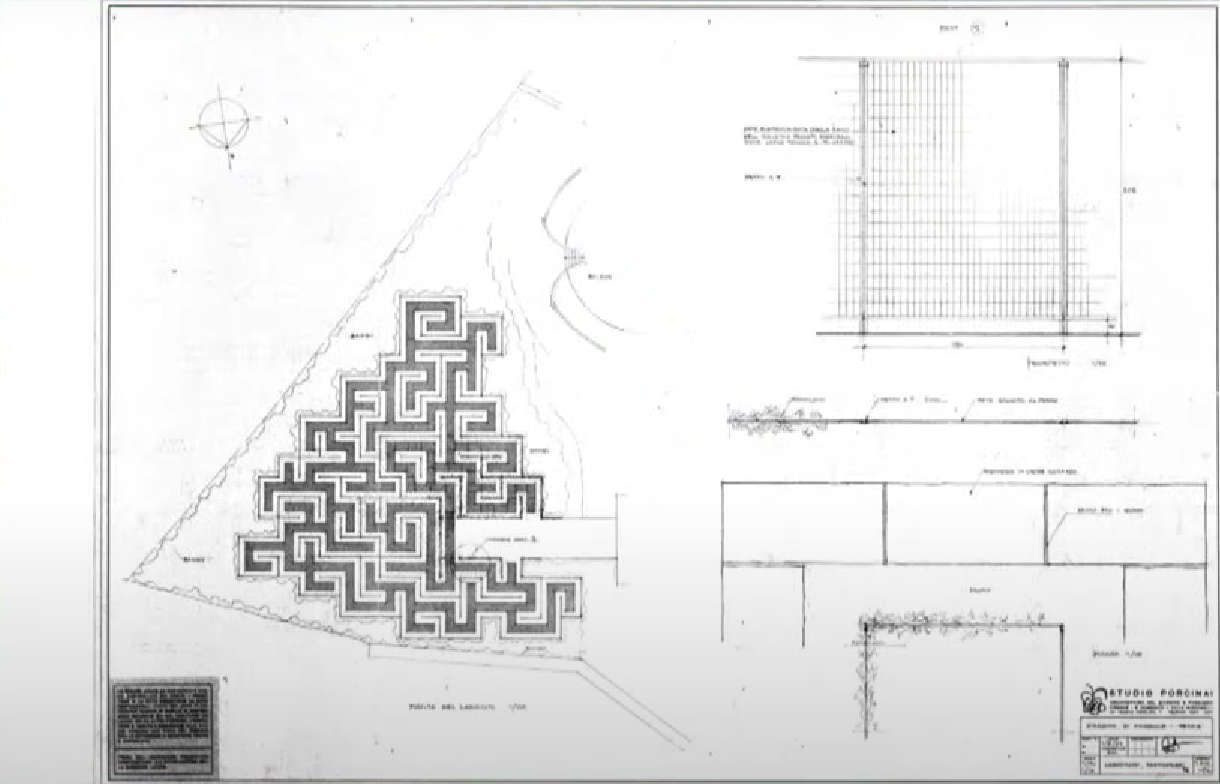

The layout envisioned by Porcinai is very particular, unusual: it is in fact based on recursive division, that is, as Ettore Selli explains, “having established the outline, the available space is subdivided through the insertion of baffles that go on to define increasingly narrow spaces until this process is maximized,” ending up composing a “geometric labyrinth with regular paths that are laid out orthogonally with one another,” and with sudden changes of direction "achieved through a constructive method that draws on the oldest information relating to the fifteenth-century maison dedalus , considered true forerunners of today’s mazes of greenery." The inspiration came to Porcinai from a labyrinth that the Brazilian architect Roberto Burle Marx had created at the Parque del Este in Caracas: in fact, the archives of the Fiesole landscape architect preserve an issue of Landscape Architecture magazine from 1963 where Burle Marx’s intervention is described, and Porcinai reports, in a pen-note, the phrase “idea also for Pinocchio.”

Another peculiarity of the labyrinth is the plants: it is not in fact a maze of hedges, as is the case in most cases. It is in fact a labyrinth made with fixed structures (nets) on whichivy (Hedera helix of the araliaceae) has been grown, which is easier and quicker to manage in maintenance.

In 2021, the labyrinth was fully restored, with an intervention designed by architect Carlo Anzilotti, costing just under 74 thousand euros and 50% financed by the Caript Foundation. “The Labyrinth in question,” Anzilotti explained in explaining the restoration project, “is of the classical type with a single entrance and a single dead end at the end of the path. The original construction includes a path paved with concrete tiles and a vertical mesh with ivy capable of creating continuous walls for a path of discovery. Over time there have been various maintenance and regulatory upgrades, but today the Labyrinth is in need of radical restoration in order to take on its former appearance and texture, as it is in a state of total degradation of the plant component.” The intervention was complex because the paving, in the labyrinth of Pinocchio Park, prevails over the earth for the replanting of the tree essences, and it was therefore necessary a systematic work of excavation to make possible the planting of the new plants, in order to return the image, legibility the functionality of the original maze. The restoration, which was carried out in full compliance with Porcinai’s original design, therefore followed three phases: first, the existing fence was dismantled and the excavation was prepared, disposing of the previously present earth, after which, in the second phase, the drainage subgrade was prepared, the drainage pipe connection and theadjustment of the disposal network, and finally, lastly, backfilling with new topsoil, installing the existing fence, and supplying and planting 600 ivy plants. The work, after clearance from the Superintendency, required about six months of work by specialized gardeners from the Giorgio Tesi Group, a major company in the nursery industry, as well as the Pinocchio Park staff who took care of the finishing touches. “The intervention of the Caript Foundation,” then commented Pier Francesco Bernacchi, president of the Carlo Collodi National Foundation, “was fundamental in order to finally be able to intervene on such an important work, testimony to the thought of a great architect like Porcinai, in a Park whose artistic importance is recognized and protected by the Fine Arts.”

The labyrinth today is one of the symbols of Pinocchio Park, and visitors find it near the end of the path: they are called to get lost in its meanders to experience what the puppet went through during the book before reuniting with his father Geppetto. An idea to make the public relive the adventures of Pinocchio, in one of the most beautiful parks in Tuscany.

|

| Pinocchio's Labyrinth: a symbol of the vicissitudes of the world's most famous puppet |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.