by Redazione , published on 30/07/2020

Categories: Travel

/ Disclaimer

Discovering the town of Certaldo, Tuscany, the birthplace of the great Giovanni Boccaccio.

Walking down the main street of the historic center of Certaldo, an abundant hundred meters paved in opus spicata and running between two wings of ancient buildings all in red brick, at a certain point, arrived about halfway, you will notice a house with a tower that stands out from the neighboring buildings, and with a neat facade: the plaques placed one above the other inform us that we are in front of Boccaccio’s house.

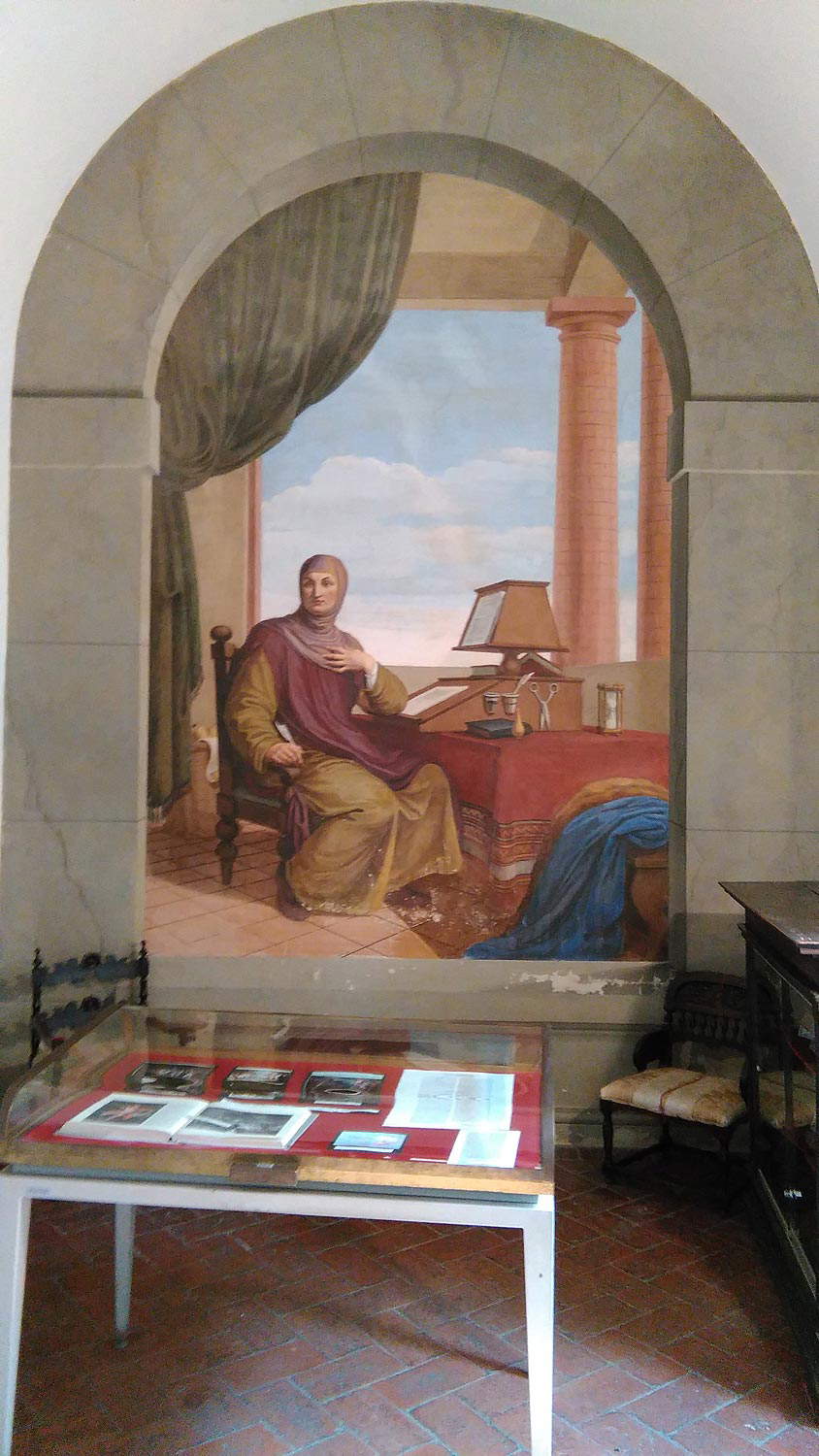

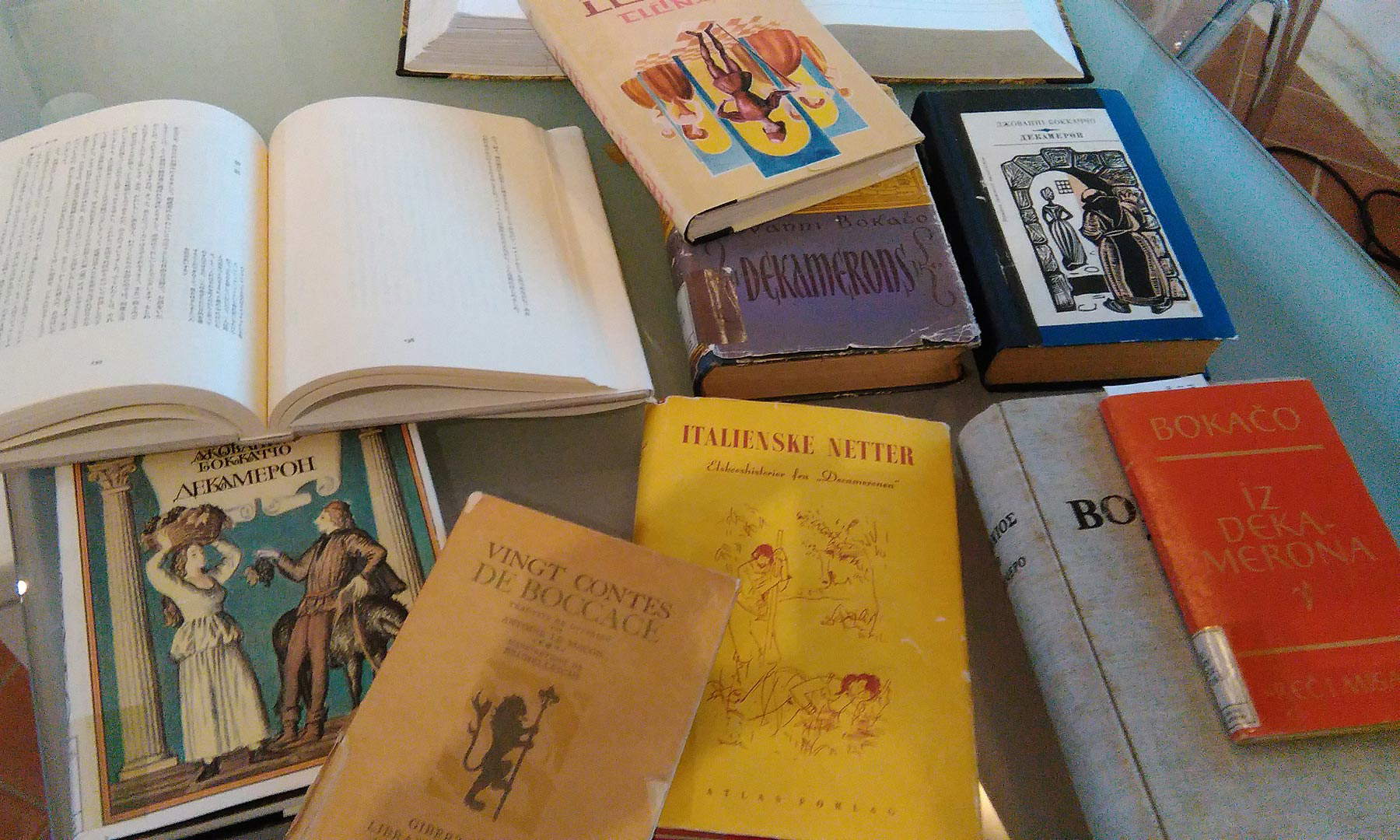

Here, in this Empolese village, in fact, the great author of the Decameron, Giovanni Boccaccio, was born in 1313, and it is thought that this building in the center of the street that bears his name is the house where he spent the last years of his existence: the news that this was his real home spread at the beginning of the nineteenth century, but even today we do not know for sure. Not only that: the original building was almost completely destroyed during the bombings of World War II, and what we see today is an almost complete reconstruction. There is also no lack of a “poet’s room,” located in the room that tradition asserts was the writer’s. Of the fourteenth century, however, there are only a few women’s shoes on display, belonging to who knows who: we can make up for it with an interesting fresco of 1826, by Pietro Benvenuti, depicting Boccaccio in his study, and with the extraordinary specialized library, the richest dedicated to the great certaldese, where numerous editions of the Decameron are preserved (in Italian, in many other languages of the world, illustrated, ancient, recent).

Certaldo, however, is not only Boccaccio. It is a village that surprises. It stands on a hill, which can be reached either by the cable car that leaves from the plain, where the modern city of industry and commerce stretches, which has almost sixteen thousand inhabitants, or by climbing a small road that passes from behind the hill, climbing among the cypress trees. When you arrive, you will find a village that has remained virtually intact since Boccaccio’s time, and what has not remained intact has been reconstructed to give the traveler the impression of finding himself catapulted into the 14th or 15th century. Certaldo is best known for its great prose writer, but in the Middle Ages the town was an important center on the Via Francigena: around here it was full of castles, churches and abbeys, hospitals, and stopping and refreshment places for wayfarers (who, of course, were not only pilgrims, since in ancient times the paths of faith were also busy trade routes). Certaldo has known a relatively quiet history, except for the aftermath of the Battle of Montaperti and especially the events of the 12th century, when it was a fief of the Alberti counts and engaged, with the other Albertian centers led by the proud Semifonte, a town that had experienced a very rapid development, in a clash with Florence. Certaldo was subdued in 1198, while Semifonte four years later: in revenge, Semifonte, the town that had wanted to challenge Florence was razed to the ground and was ordered to build nothing more on the site on which it stood. Instead, Certaldo became a sleepy agricultural center on the Florentine outskirts: the coats of arms of the vicars on the façade of Palazzo Pretorio recall the long period when the town was linked to Florence.

|

| View of Certaldo from Casa Boccaccio. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The poet’s room at Casa Boccaccio. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Editions of the Decameron at Casa Boccaccio. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Through the streets of Certaldo. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Through the streets of Certaldo. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

If one observes the village from a distance, from the plan, one of the first things one notices is the pyramidal top of the collegiate church of Saints Jacopo and Filippo, erected in the early 13th century, although it has undergone several renovations, the heaviest between the 19th and 20th centuries: the interior preserves valuable works, including a splendid fresco by Memmo di Filippuccio, a painter active in the early fourteenth century, a portrait of Giovanni Boccaccio by Giovan Francesco Rustici (an underrated genius of Florentine Renaissance sculpture ), a ciborium by Benedetto Buglioni, and then again a pair of Della Robbia terracottas, and a sixteenth-century stoup.

To get this far, the traveler will first have made a small and probably unwitting journey through 14th-century Certaldo, right from his entrance into the village, should he have passed through the Alberti gate, also 14th-century: before arriving at the church, the main one in the village, other buildings from the same period are admired, namely the Stiozzi Ridolfi Palace with its crenellated towers, the Market Loggia, the Palace of Scoto da Semifonte, and the tower-house of the Della Rena family (for which a small detour must be made). Upon arriving at Palazzo Pretorio, one will find that Certaldo has no real square (unless one makes an exception for Piazza della Santissima Annunziata, which is actually little more than a widening): even the main town building has no square in front of it. So, we will consider via Boccaccio as a single, large square on which the life of the town takes place: a life that is slow and silent, however, enlivened only by the bustle of tourists, the tolling of bells, the resigned vociferating of the few inhabitants and, around lunchtime, the smell of onion soup (an institution, in Certaldo) coming out of the town’s restaurants.

Before entering the palace, however, one will want to complete the tour of Certaldo by going to Via del Rivellino, a steep uphill street that reaches the walls running between medieval tower houses, and perhaps visiting the very unique Museo del Chiodo, an original collection of nails of every age and shape (but not only: there are also objects and figures made only of nails) set up on the first floor of the ancient Palazzo Giannozzi thanks to the work of Giancarlo Masini, carpenter and storyteller of the village.

|

| Certaldo, Collegiate Church of Saints Jacopo and Filippo. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Madonna and Child by Memmo di Filippuccio. |

|

| Palazzo Pretorio. Ph. Credit Museo Diffuso Empolese Valdelsa |

|

| The Museum of the Nail in Certaldo. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| A room in the Palazzo Pretorio. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Vault with vicarage coats of arms in the Praetorian Palace. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The tabernacle of the Executed by Benozzo Gozzoli (1464-1465). Ph. Credit Benozzo Gozzoli Museum Castelfiorentino |

Palazzo Pretorio (or Vicar’s Palace, since it was from 1415 the seat of the Vicariate of Valdelsa, one of the territorial subdivisions of the Florentine Republic: each vicar affixed its own coat of arms to the facade, which is why we see it so decorated) is, together with the Museum of Sacred Art located in the former Augustinian convent (the collection of gold funds, including works by the Master of Bigallo, Cenni di Francesco and Puccio di Simone, is interesting), the place where Certaldo’s historical-artistic memory is preserved. The itinerary has recently been renovated and is divided into three parts. It begins with the Archaeological Section, the ’antiquarium that collects the most remote testimonies. It then continues with the Museum of Justice, the route that takes visitors to discover the place where justice was administered in ancient times, but not only, since this is where the works of art are concentrated: the Knight’s Chamber with the 15th-century Madonna and Child by Pier Francesco Fiorentino, an author trained with Benozzo Gozzoli and who we also find in the audience room with two other frescoes (a Pietà and an ’Incredulity ofSt. Thomas), and in the Hall of the Vicar, the most important room in the building, ending with the frescoes that once decorated the tabernacle of the Executed (they are the work of Benozzo Gozzoli and were detached from their original location for conservation reasons: they have therefore been arranged to recreate their ancient arrangement). Finally, the last part, the Gallery of Contemporary Art, where the works that great artists from the 20th century onwards have created to pay homage to Boccaccio and the Decameron stand out.

Finally, also worth a visit is the Tea House Garden of Hidetoshi Nagasawa, a Japanese artist who is a regular in Tuscany. It was 1993 when a Japanese ceremonial tea house, donated to Certaldo by the twin city of Kanramachi, was installed in a small walled garden with no specific function inside the Palazzo Pretorio. In 2001, as part of the regional Dopopesaggio project, Nagasawa was commissioned to create an environmental artwork that would contextualize the ceremonial tea house within the Palazzo. And lo and behold, the experiment gave rise to the “Tea House Garden”: a set of wall elements and tree essences that connect East and West, become a symbol of friendship between the two cities, and reference Japanese philosophy. A work that gave full meaning to a space in the Palace and to a house that had hitherto been out of context. Miraculous interventions of art, fruitful dialogues between ancient and contemporary.

Article written by the editorial staff of Finestre sull’Arte for UnicoopFirenze’s “Toscana da scoprire” campaign.

|

| Certaldo, a piece of the Middle Ages in Boccaccio's hometown |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.