Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Liguria

A marvelous land squeezed between the sea and the mountains immediately behind: this is Liguria, and even among the museums of this region it is possible to come across the presences of fantastic animals and creatures. From the coasts of the Levante Riviera to the Ponente near the French border to Genoa, here are the animals we found in Liguria. The project is led by Finestre Sull’Arte in collaboration with the Ministry of Culture and aims to introduce museums to everyone through unprecedented points of view on the works, remembering that museums are safe and suitable places for everyone, families, couples, friends, colleagues, individual visitors. Here then is another trip!

1. The Hydra in Gregorio de Ferrari’s canvas at the National Galleries of Palazzo Spinola

The Hydra of Lerna, according to Greek mythology, was a monster resembling a large sea reptile with nine heads: extremely venomous, it was able to kill with just its breath, it also had great intelligence. Its heads could grow back if severed. It was confronted by Hercules (Heracles in Greek) in the second of his twelve labors: the hero was helped by his friend Iolaus, who cauterized the heads once they were cut off so that they would not grow back, and in the end Hercules succeeded by crushing the central head. The canvas created by Gregorio de Ferrari (Porto Maurizio, 1647 - Genoa, 1726), one of the most important painters of late 17th-century Liguria and one of the great names in Genoese Baroque decoration, is part of a series of paintings dedicated to the famous mythological hero that once adorned the rooms of Palazzo Cattaneo Adorno. The four works from the Labors of Hercules cycle were acquired by Palazzo Spinola in 2014, along with three other canvases, also by Gregorio de Ferrari, with themes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. In De Ferrari’s painting, Hercules is depicted pouncing on the fearsome monster, painted at his feet about to be defeated, in a rather convulsive composition but through which it is possible to glimpse great formal balance.

2. Jan Verbeeck’s Fantastic Creatures of the Temptations of St. Anthony at the National Galleries of Palazzo Spinola

This problematic painting, once attributed to Pieter Bruegel the Younger and now referred to the Flemish painter Jan Verbeeck (Mechelen, c. 1520-c. 1569), depicts the episode of the temptations of St. Anthony the Abbot: monstrous demonic apparitions allegedly tormented the saint trying to threaten his faith, but the saint was able to resist. In keeping with typical Nordic iconography, the temptations are depicted not only as beautiful and provocative young women (these are the ones we see next to the saint), but also as bizarre fantastical creatures resulting from the crossbreeding of several animals, singular monsters that are the result of a great imagination that draws on the more famous precedents of Jheronimus Bosch, another artist known for the creatures that populate his paintings. A curiosity: it is said that this painting greatly fascinated Gustave Flaubert, who saw the work while visiting Palazzo Balbi in 1845, where it was formerly located. From the vision of this work would come the work La Tentation de Saint Antoine, written in no less than three versions.

3. The cerberus in Giovanni Battista Carlone’s fresco at the Royal Palace of Genoa

Among the rooms of the Royal Palace in Genoa, and more precisely in the Chapel Gallery, on the west wall, if you look up you will notice a fresco whose protagonist is still Hercules, grappling with another mythological monster: it is Cerberus, the three-headed dog that stood guard at the entrance to the underworld. The fight with Cerberus represents the last of the twelve labors, the feats to which Hercules had been forced for killing his wife and children in an access of anger provoked by the goddess Hera. The last toil consisted precisely in bringing Cerberus alive to Mycenae. And in this fresco by Giovanni Battista Carlone (Genoa, c. 1603 - 1684), another great protagonist of the Genoese Baroque, Hercules, wearing the skin of the Nemean lion defeated in the first effort, is caught in the act of capturing Cerberus, defeated by his strength alone. Carlone depicts Hercules clutching the body of the hellish animal with a mighty chain that will immobilize him. The Gallery includes other depictions of the Hercules myth and is presented with strikingly scenic images, with life-size figures looming over the visitor (the scene of the last effort is painted above a door) to draw him into the events with a strong theatricality that has few other parallels in Genoese palaces of the time.

4. Marsyas in Domenico Parodi’s fresco at the Royal Palace of Genoa.

Marsyas, in the stories of Greek mythology, was a satyr, that is, a creature half man and half goat. Like the other satyrs he excelled in music, and in particular was an extraordinary player of the aulos, the typical one- or two-reed flute of ancient Greece. He was so good that the people of Anatolia, where he lived, believed he was better than Apollo, the god of music: word reached Apollo himself, who decided to challenge him. The two established that the winner would earn the right to do with the loser whatever he wanted: Apollo eventually prevailed, although with methods that were not very “sporting” (according to one version of the myth, after an initial tie decreed by the muses, he imposed on Marsyas to play with the inverted flute; according to other versions, he proposed to sing and play at the same time: in both cases, Marsyas’ instrument would not allow him to beat the god), and he decided to punish Marsyas’ pride by flaying him. Domenico Parodi (Genoa, 1672 - 1742), however, decided to depict not the bloodiest moment, but the contest, in the fresco that adorns the Mirror Gallery of the Royal Palace, one of the building’s most celebrated and celebrated rooms. The Gallery, in 1650, was decorated only by the paintings and statues that were part of the collection of Giovanni Battista Balbi, son of Stefano, the building’s first owner. The current appearance is due to Domenico Parodi himself who, around 1725, for the new owner Gerolamo Ignazio Durazzo imagined the scenic Gallery with stucco, gold, mirrors and paintings that were meant to envelop the visitor to capture and fascinate him as much as possible. Even the scene with Apollo and Marsyas illusionistically breaks through the ceiling: it is as if the Gallery’s vault opens up to the sky (even the clouds cover the stuccoes to give a more realistic effect) to make us witness the contention. Next to Apollo here are some of the muses: Melpomene, muse of tragedy, with a sword, behind we see instead Urania, muse of Astronomy with a globe, and standing to Apollo’s left, Euterpe, music, depicted with a trumpet.

5. Medusa in the fight between Perseus and Phineas by Luca Giordano at the Royal Palace in Genoa.

An important work of the late 17th century, the Struggle between Perseus and Ph ineas by Luca Giordano (Naples, 1634 - 1705), is preserved at the Royal Palace: it depicts an episode from the myth of Perseus, taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses. It is the one that follows the liberation of Andromeda, whom Perseus rescues from the clutches of the sea monster that was undermining her: the beautiful young woman had in fact been betrothed to Phineas, the son of the nymph Anchinoe and therefore a descendant of Poseidon, the sea god who had sent the monster against Andromeda to punish the pride of her mother, who believed that her daughter was more beautiful than all the Nereids, the sea nymphs. For saving Andromeda, Perseus obtained her in marriage: this aroused the wrath of Phineas, who showed up at the wedding banquet along with his warriors. Perseus got the better of his enemies by displaying the head of Medusa, the fearsome creature with a woman’s face and snake hair who was able to petrify with her gaze. The severed head had retained this power, and in the painting Perseus uses it as a weapon against his opponents; Phineas knows this, and tries to protect himself with his shield (curiously, the carapace of a tortoise). It is another iconic Baroque painting, characterized by great theatricality and scenic devices, such as the idea of inserting the figure of Phineas above a group of overpowered warriors, and that of inserting the two tall columns with the red drape around them to sharply divide the scene into two parts.

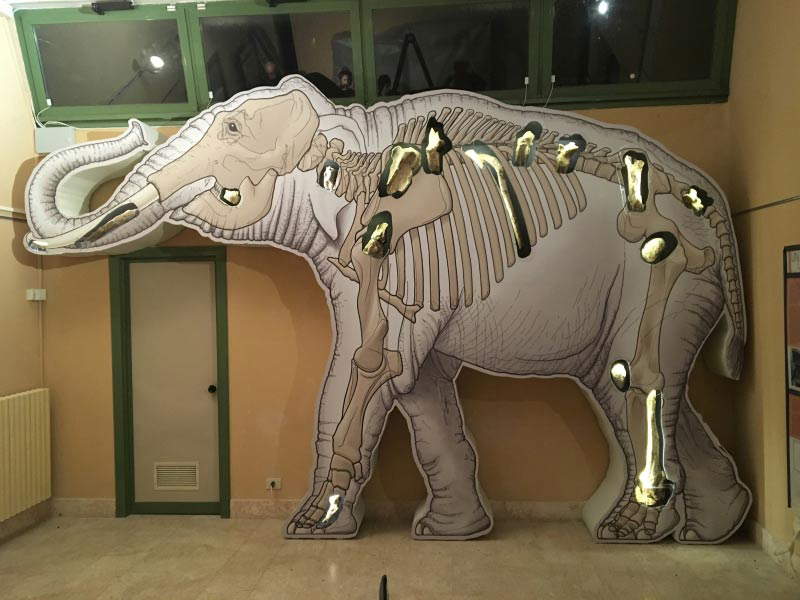

6. The elephas antiquus from the Balzi Rossi Prehistoric Museum in Ventimiglia.

Yes, we know, we are not really talking about a fantastic animal, since theelephas antiquus of the Balzi Rossi Prehistoric Museum in Ventimiglia really existed, but it is nevertheless a prehistoric animal that has... many fantastic sides, starting with the fact that in ancient times finds of remains such as those preserved in Ventimiglia (in the skull the nasal holes are fused into a single opening in the center of the forehead and the skeleton is characterized by very long legs), in the caves of Sicily and Greece, fueled in ancient times the birth of myths and legends. To explain the discovery of remains such as these even gave rise to the myth of the cyclops! The one in Ventimiglia, on the other hand, has a much less mythological history: it was 1899 when the French anthropologist René Vernau reported the discovery of a European elephant or ancient elephant (an animal the size of today’s African elephant, and which in prehistoric times was widespread throughout Europe: it became extinct about 30.000 years ago, due to the hardening of the climate on our continent) found in 1894 by a quarry worker at the Barma Grande cave. It is a 10-year-old, large animal, probably male. Some elements of this young animal, probably felled at the bottom of the cave, occur in anatomical connection, as the discoverers had already suggested. These are essentially the legs (front and hind legs) that were abandoned on the spot, preferring other parts that were richer from the food point of view. Some traces of burning and heating have produced variations in the color of the bones, as well as visible traces of the tools used by Neanderthals to flay the animal. There are also documented traces of shaping on ivory fragments that do not match the rest of the material coming from the Balzi Rossi. These objects, moreover, speak of technological complexities unsuspected by Neanderthals. The remains ofelephas antiquus thus tell of a complex scenario in which the Barma Grande constituted an area of refuge for the ancient elephant during the period of climatic cooling. Neanderthals coped with this period and settled at Balzi Rossi on several occasions: they were able to take advantage of the particular conformation of the site, being able to push prey into the natural trap formed by the Barma Grande, so that they could take down these proboscideans and then cut and consume them directly on site.

7. The swan of the Ligurians in the pendants of the Chiavari necropolis.

The ancient Ligurians are also known as the people of the swan: the reference is to the legend of the mythical king of the Ligurians Cicno, a great friend of Phaethon, son of the Sun god, who obtained permission from his father to be able to drive the sun chariot. He was unable to steer it, however, and came too close to the Earth, running the risk of setting it on fire: to prevent him from destroying the planet, the god Zeus electrocuted the young man, causing him to fall into the waters of the Eridanus (Po) River, where he drowned. Cycnus was shocked by his friend’s death, and the gods, moved to compassion, transformed him into a swan. According to another version of the myth, Cycnus was instead transformed into a swan by Apollo after his demise. In any case, the splendid animal is a symbol of the Ligurians and is therefore found in many representations, such as in this bronze pendant, found in the tomb of a woman belonging to the Iron Age Ligurian Tigullii tribe, which is now on display in the National Archaeological Museum in Chiavari. The object has bird-shaped projections on both sides, with the beak pointing downward and the head connected to the suspension ring. Pendants with the same shape were produced in central Italy to be applied generally to a shield; the two specimens found at Chiavari, on the other hand, were part of a female trousseau and were connected by a chain to some ornamental object, perhaps a necklace.

8. The sphinxes of the Antiquarium of Albintimilium (Ventimiglia).

The Antiquarium of the Roman city of Albintimilium, corresponding to present-day Ventimiglia, preserves a funerary monument found by archaeologist Girolamo Rossi (Ventimiglia, 1831 - 1914) in excavations he supervised in 1886, consisting of anarula (i.e., a small votive altar) with a beveled tympanum front, which bears on its front face an inscription concerning the burial desired by a certain Lucius Allius Ligus for himself, his wife Valeria Thallusa, and their son Lucius Allius Allianus, who died at the age of only 20. The monument was flanked by two gray stone sphinxes. The first, complete with base and well preserved, has a large and elongated female body, while the head and wings are small and disproportionate. The wavy hairstyle with side ringlets and bun at the nape of the neck reproduces a type attested in the Tiberius-Claudian age (AD 14 to 54). The second one, on the other hand, extensively restored in antiquity and lacking support, has a very large and elongated body, the wings tiny and badly remade upper part in concrete, as well as the legs. The head, which has a concrete neck, does not seem relevant. The sphinx, a mythical animal with the body of a lion and the face of a woman, was often used in ancient funerary monuments: in fact, it was considered the guardian of burial areas. This is precisely the significance that the sphinx holds in the Albintimilium burial monument where it interprets, in an extremely rigid and schematic language, an iconography widely used in Cisalpine funerary contexts.

9. The bull Api in the coinage of the Roman Villa of Varignano.

In the Roman Villa of Varignano, which is located just before Porto Venere in one of the most scenically beautiful areas of Italy, a bronze coin was found minted at the time of Emperor Julian and produced in the mint of Lugdunum (present-day Lyon, France) in 362-363 AD.C. which bears on its reverse the image of the bull Apis, worshipped by the Egyptians as a herald of the god Ptah, but also as a deity of their own. It is therefore not only the image of a fantastic animal, but even of a divine animal: in fact, the Egyptians attached great importance to Api, a symbol of strength and a brave spirit, and thus linked to the concept of kingship.

10. The Medusa in the mosaic of the National Archaeological Museum in Luni.

Dating from between the late third and early fourth centuries CE, this mosaic comes from the Domus of Oceano in Luni, a residence so called because it also had a larger mosaic, still on view at the National Archaeological Museum in Luni, depicting the face of the god Oceano with two cupids riding dolphins caught fishing in a sea populated with fish, mollusks and crustaceans. The mosaic with the gorgoneion, or Medusa’s head, was located in the corridor that gave access to the room with the Ocean tessellation. On a white background is traced a rectangle divided into four squares that house as many distinct elements; in the first is depicted the gorgoneion. Medusa’s head also has two wings, while her hair, as per typical iconography, is made of snakes. A large flower divides it from the panel that houses instead the depiction of a Silenus who has two points of view: entering the corridor he has the usual “senile” appearance with a long beard, on the other side we read instead the face of a young man whose old man’s beard serves as his hair. Closing the figurative system is another multi-petaled flower. The mosaic is polychrome, with black, gray, blue, white, yellow, ochre, red, brown, and green marble tiles; details are rendered with glass paste tiles.

|

| Animals and fantastic places in Italy's museums: Liguria |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.