Why do so many key masterpieces from the GNAM in Rome have to stay in China for eight months?

The first had been the Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, which had sent its jewels to Texas in early 2020: about forty select pieces including Caravaggio’s Flagellation, Parmigianino’sAntea, Guido Reni’sAtalanta and Hippomenes, and Titian’s Danae, i.e., works for which we often go specifically to the Neapolitan museum. Then it was the turn of the Uffizi, which in the fall of the same year sent 22 works to Hong Kong, but at least took care to communicate the absence well in advance (the announcement was made a year earlier), not to deplete the collection too much even though it gave up some masterpieces such as Botticelli’sAdoration of the Magi and Perugino’s Magdalene, and to transparently reveal what the quid pro quo was (600,000 euros). Now the National Gallery of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rome has gotten involved, too, but it has gone further: not only, in fact, has it sent to China some key masterpieces by artists who are underrepresented in Italian museums (Van Gogh, Monet, Cézanne, Klimt, Modigliani), but it has set a record for the longest absence from the venue, since the Chinese tour has clocked up the duration, barring extensions, of no less than eight months, from July 2022 to February 2023.

It now seems clear that we will have to get used to the idea of our public museums shipping blocks of works abroad in exchange for financial support, since this unpleasant habit seems to be spreading with increasing consistency. However, there is a way and a way to communicate the absence of a significant core of masterpieces from its home, and the National Gallery of Rome has probably chosen the wrong ways. The news of the departure for China passed quietly (it was mentioned only on these pages and in a few other newspapers: perhaps they can be counted on the fingers of one hand), and the exhibition became known only when, by then, the works were already on their way to the East.

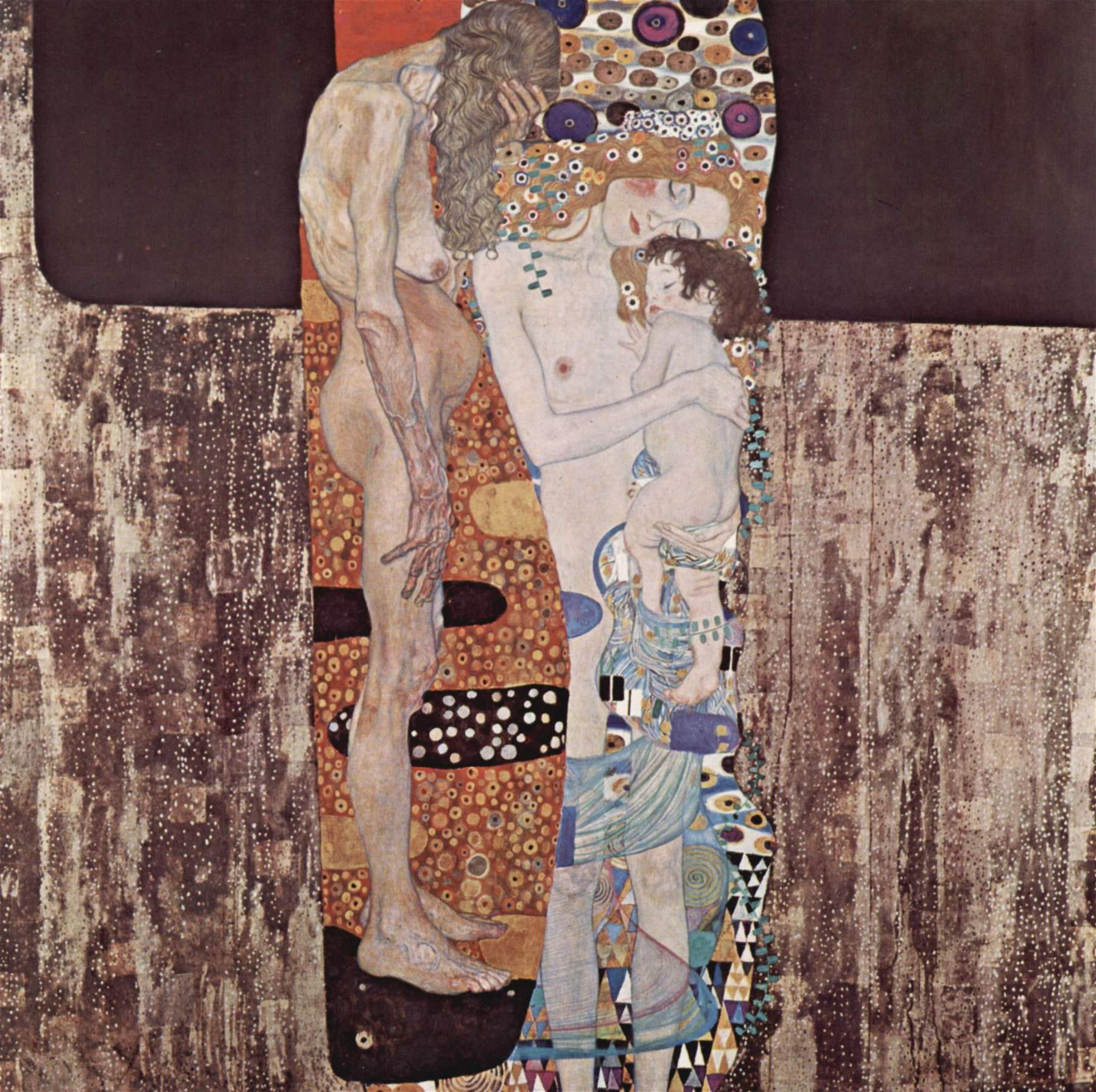

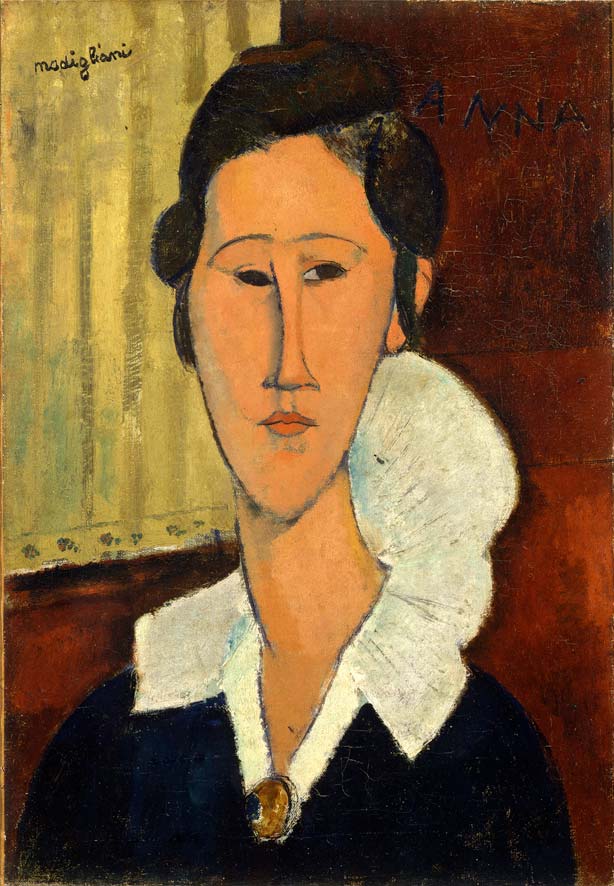

Moreover, it seemed that initially the exhibition was only one, and that the works would be away from Italy only from July to October, for three months: only later, when the exhibition was over, did the public learn that there would be another exhibition, in Chengdu, from November until February 26. Let’s hope then that when the second stage is over, a third one will not be announced as a surprise. Of the Chengdu exhibition, moreover, there are few traces to be found around: a launch by the Chinese agency Xinhua, translated into Italian by Agenzia Nova, an article in the Global Times, a blurb on the website of the Italian consulate in Chongqing, another on the website of the Italian Foreign Press Agency. In short, in Italy practically no one has broken the news. But that’s not all: if you go on a visit to the National Gallery and want to look for, say, Van Gogh’s Gardener andArlesiana or Klimt’s Three Ages, which are among the very rare of their works in Italian public museums (there are six in all, three by Van Gogh and three by Klimt), you will find no sign informing visitors of their absence, as would be good practice in such situations, at least for key masterpieces. Or if there is, it is well hidden. True, there is a scant explanation on the National Gallery’s website, but it is not given any prominence (it is not on the home page nor is it linked in the What’s on section: in short, you find it by getting to it from Google and putting in the appropriate keywords, so you basically get there if you already know the works have left), and then it conveys contradictory information.

Indeed, it says there that “in September 2022, a selection of masterpieces from the National Gallery left for China to be displayed in two temporary exhibitions in Beijing and Shanghai.” Meanwhile, the works left in July: the correct dates can be found on the Italian site of the Chinese organizer of the exhibition, while photos of the July 24 opening can be found on some Chinese sites. Also, the site remembers when the works left (albeit providing a date two months late), but does not say when they will return. Then, the second stop of the exhibition is in Chengdu and not Shanghai. Again, the organizer’s website states that there are 62 works in the exhibition, belonging to 47 artists, while the notice on the GNAM website lists exactly half of them (not having visited the exhibition in China we cannot say who is right). Finally, it moves to sympathy the idea that “the intense activity of outgoing loans to Italy and abroad [...] has allowed the room substitutions and the 65 temporary exhibitions of the National Gallery from 2015/2016 to date, to exhibit at the museum about 2000 works from the collection, including some never exhibited before and new acquisitions.” In short, in the future we will have to hope that GNAM will again send one of the only three Klimt works we have in our public museums to China if this is the only way to pull another still life by De Pisis out of storage. Incidentally, it should be recorded that the two Van Gogh works are leaving at the very time that an exhibition dedicated to Van Gogh is being held in Rome (with a block of forty works from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, as usual: but they at least have a collection of almost three hundred Van Goghs, so they have no problem replacing the absences).

One can also have some sympathy for a museum that deprives itself, in one fell swoop, of dozens of works in exchange for adequate compensation (despite the fact that it is a practice that is not exactly viewed very well by ICOM), if, however avoids giving up key works, if the artists it sends off-site do not end up becoming underrepresented, if everyone is notified of the absence in good time by giving it proper notice, if visitors are properly informed (and thus if inside the museum, in place of the absent painting, a poster is put up saying in large letters where the painting is, for which exhibition, and how long it is off-site), if there is full transparency about the whole operation. If, therefore, there has been a quid pro quo, let it be done as the Uffizi did: let it be communicated in clear letters. If there was not and it was therefore a pure diplomatic move, say so anyway with the utmost clarity: at least the public will be able to get the full picture and draw its own conclusions.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.