The actuality of Giovanni Urbani. A text by Giorgio Agamben with foreword by Bruno Zanardi

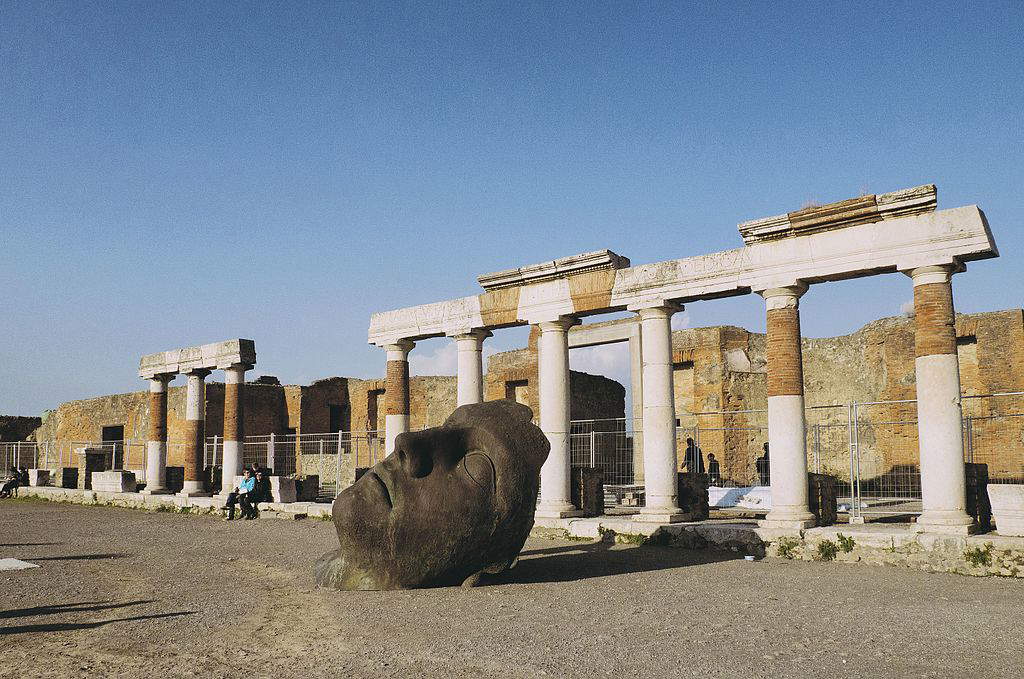

In my recently published article in Finestre sull’Arte I took up a very interesting article by Andrea Carandini published last August 21 in “Il Corriere della Sera” in which the Roman archaeologist writes about the great civil and cultural issue of the protection and enhancement of the artistic heritage. Article in the last part of which Carandini also writes about the complex issue of the preservation of Pompeii. For my part, I quoted an opinion expressed by John Urbani half a century ago on the “Pompeii problem.” Namely, that this site can be preserved only when it is considered for what to all intents and purposes it is. A city. In ruins, but a city nonetheless. Which would oblige (I add it, today, 2023) to free it from the indecent economy of mass tourism of which it is a victim thanks to the “valorization” desired by former minister Franceschini and from there find a way to go in the direction indicated by Carandini. That is, to intervene on the elevations of the domus and make them “a continuous whole.” A theme for giants in architecture, to combine in aesthetic, critical and technological terms the preservation of a city of two thousand years ago with the present day, and to do so without resorting to the usual “architectural” materials such as concrete (reinforced and non-reinforced), cretinous bands of faux-rusted “corten steel,” cans of “nature-green” paint, and anything else of bleak incongruity a and sadness designed by one of the 153.692 graduate architects (CNAPPC) that Italy has today: roughly one per km2 if you take away from the 302,073 km² of its surface area lakes, rivers, mountain peaks, banks of Apennines no longer cultivated therefore increasingly subject to a kind of Amazonian reforestation and so on.

That said, it may be added that the current director of Pompeii, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, in his autobiographical notes has always placed Giorgio Agamben’s books among his formative readings. But he evidently does not know that the Roman philosopher always listed among his teachers John Urbani (1925-1994), that is, the best intelligence who has dedicated himself to the preservation of our artistic heritage in the last half-century, also developing from the direction of the Central Institute for Restoration a perfect model for its protection. The planned and preventive conservation of heritage in relation to the environment. A model defined in detail that perfectly fits with the problem of Pompeii, the same one that Carandini also mentioned in the “Corriere” talking about “planned maintenance.” So that I publish for the readers of “Finestre Sull’Arte” an essay by Agamben on Urbani. For three different reasons.

The first to honor Zuchtriegel for his philosophical interests and to acquaint him with a piece of Agamben’s work evidently unknown to him. So that he can measure his own role as director of Pompeii against the figure of a rare superintendent who was prepared to be one, namely Urbani. The second, to make it clear to those who read “Finestre Sull’Arte” what studies and depth of thought every superintendent should have in order to be able to carry out the not simple task of recomposing the special oxymoron that is preserving the past in the present. The last, to clarify that the preservation of an artistic heritage that has gone over the millennia infinitely stratified on the territory which is that of Italy and the Italians is an enterprise of enormous technical-scientific, organizational and, indeed, thinking difficulty. A clarification that unfortunately no University, Heritage School, etc. has been able to make. In fact, if those schools existed, and functioned, they would have long since taught their students that the discovery of a burned corpse in Pompeii, that is, in a city gone buried by the lava of Vesuvius, is not a rare cultural or anthropological event, since there are already thousands (“Pompeii Sites”) of those dead in sight, all rendered in plaster casts using the same system developed by Giuseppe Fiorelli in 1863, exactly one hundred and sixty years ago. And even the existence of that school long ago would have avoided the excited statements of the minister on duty when faced with yet another poor charred corpse. His telling reporters and television stations, “Pompeii is a site that never ceases to hold surprises for us.” And perhaps, I add in passing, those schools would also have avoided the recent move (escape?) of the Mibac chief of staff to the Football League, that is, to a body where a goal is a goal, a goaltender is a goaltender, a great footballer is a great footballer, and a burned corpse, when one is found in a penalty area, is a burned corpse.

Bruno Zanardi

Topicality of John Urbani

from G. Urbani, For an archaeology of the present, Skira, Milan, 2012

1. ARCHEOLOGY

The figure of John Urbani has been acquiring in recent years an aura of exemplarity, not only because of his public commitment as director of the Central Institute for Restoration, but, as is usually the case whenever Italian culture wants to make up for the special inattention it reserves for those it fails to assimilate, also because of his biography. So that - also thanks to Raffaele La Capria’s impassioned evocation of him - the “handsome and damned” dandy stood side by side with the impeccable official, the glamour of private existence covered with its shadow the severe punctuality of public life.

Clearing the field of this false dichotomy, the present book [G. Urbani, Per una archeologia del presente, Skira, Milan, 2012], which brings together a significant, though certainly incomplete, selection of his essays and articles on art, allows us to discover perhaps for the first time Urbani for what he was: not so much - or not simply - an extraordinary philosophical mind, in many ways ahead of the Italian philosophical culture of those years and an art critic in every respect exceptional, but rather and first and foremost a man determined to look lucidly at the time - obscure as perhaps every time is for those who have decided to be intransigently contemporary with it - in which it was his turn to live. The title “For an archaeology of the present” (which is Urbani’s own) is intended to do justice to this lucidity and this decision, so arduous to exercise at a time in Italian history when communist and Catholic culture were preparing to suffocate in their palintrope embrace every possible otherness.

The plane of immanence on which Urbani seeks his confrontation with the present is art - but an art understood archaeologically as humanity’s past. This is not, here, a simple reprise of the Hegelian theorem on the death of art, which Urbani accepts only insofar as he specifies and declines it through novel corollaries. Art is, yes, as in Hegel, something past, but not dead, for it is, indeed, precisely in its relation to this past that the fate and survival of humanity is at stake. Precisely insofar as it is a past-so says the first corollary-art finds itself in the impossibility of dying.

Here the term “archaeology,” which Urbani uses before Foucault made it a technical term in his thought, acquires its strategic meaning. Indeed, archaeology defines that character of our culture whereby it can only access its own truth through a confrontation with the past. This definition may certainly appear as a consequence of the professional strain of a man who had chosen to devote his life to the preservation of the art of the past. But it is not so (or not only so). Archaeology for Urbani is an essential anthropological component of Western man, understood as that living being who, in order to understand himself, must come to terms with what has been. Even more radically than in Foucault, archaeology defines, that is, the condition of man who finds himself today for the first time confronted with the totality of his history and, yet - or, perhaps, precisely because of this - unable to access the present. The question that guides Urbani’s entire interrogation therefore sounds, “what is the meaning of the presence of the past in the present?” where the seemingly contradictory formula (“presence of the past in the present”) is but the most rigorous expression of the historical situation of a living being that can survive only through “the material integration of the past” into its own spiritual becoming. The formula also means, however, that the only possible locus of the past is, as a matter of course, the present and, together with and just as obviously, that the only way into the present is the inheritance of the past, that living one’s present necessarily means knowing how to live one’s past.

It is significant that Urbani, choosing as the epigraph for his book Around Restoration a phrase from Plato, consciously alters it by translating as “past” the Greek word arché which means “origin, principle” (and also “command”): “the past is like a deity who when present among men saves all that exists.” The principle, thearché is not a mere beginning, which then disappears into that to which it has given rise; on the contrary, precisely because it is past, the origin never ceases to begin, that is, to command and govern not only the birth, but also the growth, development, circulation and transmission -- in a word: the history -- of that which is brought into being.

It is in this perspective that one must take seriously Urbani’s paradox, according to which art is something of the past - it is, indeed, as it were, the very figure of humanity’s past - and yet, precisely because of this and to the same extent, that of which maximally it goes in the present. Foucault once wrote that his archaeological investigations of the past were but the shadow scope of his theoretical interrogation of the present. What in the French philosopher is a criterion of method seems in Urbani to acquire an ontological consistency, as if past and present were not only not intellectually separable but coincided punctually according to being and place. As the close of the article that gives this book its title states, the present is something like an “archaeological layer,” “human and true only if one succeeds in ’excavating’ it, if one succeeds, that is, to make earth of its illusions and dig up its stupid idols as poor furnishings, from which, having fallen the myth, there remains with the dust and indestructible as it is, the trace of what we really are.”

2. ART AND CRITICS

To the Hegelian theorem about the death of art, Urbani adds another important corollary. Art has not simply ceased to exist, but has, rather, transformed itself into critical reflection on art. As early as 1958 a great art historian, Sergio Bettini, wrote that “perhaps never before has it become clear how inevitable it is that the problem of art and the problem of criticism converge.” Urbani absolutizes this convergence and uses it as the cipher that allows him to decode the apparent complications and not always edifying ambiguities of the art that was contemporary with him (and that, in its larvae drifts, still continues to be so for us). The identification of art and criticism became possible at the moment when, through a slow process of metamorphosis-which coincides with the birth and development of modern aesthetics-art is transformed into an “objective representation of aesthetic feeling,” only as such an object of evaluation and estimation.

If the work is but the representation of aesthetic feeling and if this is inseparable from the aesthetic judgment that perceives and ascertains it, then the being-work of the work of art is erased and it necessarily resolves itself into a critical operation on art. “Contemporary art,” he writes, “insofar as it gives itself to itself as the object of such representation-that is, insofar as it arises as a critical reflection on art-produces works that are, so to speak, already erased, that is, non-works, but objective representations of an investigation accomplished in its making, thus not further explicable.” In this sense that Urbani reads the famous Desanctisian dictum that “art dies, criticism is born.” criticism arises from the shattering of the original unity of art, science and technique in the work and is, therefore, nothing but “a cunning of reason” to maintain a relationship between them, but "nothing more than any relationship at all, because it is fictitious, because it is based on what art, science and technique no longer are, that is, they have ceased to be precisely that from the moment that from art criticism was born."

It is in the 1960 essay on Burri that the transformation of art into critical reflection is caught and exemplified flagrantly. Against the insulting - and unfortunately still current today - interpetration of the readymade as a work of art, Urbani recalls that "Duchamp had the precise consciousness of operating not as an artist, but as an ideologue or if you prefer as a philosopher in the original sense: trying to reverse in actions his own line of thought. As a ’non-artist,’ he understood that the conditions of modern thought no longer included the possibility of an artistic representation of reality through objects. Art’s road to reality was inexorably blocked by an insurmountable obstacle. The obstacle was art itself, constituted through the centuries in Western thought as an ’autonomous reality.’ A reality that was indifferent and different from natural reality, but almost other than the latter to be perceived and suffered in its pure phenomenal evidence, in its formalistic apparatus. It was therefore pointless to invent yet another form of art: the irreconcilability of art and reality would not cease until human consciousness found a whole new way of standing before reality. This new way, with an insight that remains among the most brilliant in modern thinking about art, was tested by Duchamp with actual existential acts, such as readymades can be called, not with some ’painting’ or ’sculpture.’ In fact, in order to give rise to a readymade, it was necessary that the act of creation be, as it were, transported from the area of art to the area of reality, where it would give objects a brand new meaning: that of being different from themselves insofar as they were individuated, elected, remade, or rather made in the original manner of poiesis."

Nothing is understood of the singular historical fate that led to the birth of the contemporary art museum (a phenomenon about which Urbani never tires of irony) and the singular metissage of artists and curators that resulted, if one does not reflect on what Urbani had prophetically seen as early as the early 1960s: the confusion - certainly not accidental - between art and critical reflection and the consequent eclipse of the dimension of the work. And artists and curators would do well to reflect on this early diagnosis, instead of persisting in presenting, one does not know whether out of naiveté or cynicism, as works of art their - in any case repetitive with respect to Duchamp’s gesture - critical operations on art and as thoughts or “concepts” what is but the shadow that the dissolution of the work casts over artistic making. Roman law knew the figure of the curator, who supplemented with his declaration the legal incapacity of minors, madmen, prodigals, and women: in Urbani’s perspective, it is because of a similar irresponsibility in the face of their historical task that artists and curators seem today to be forced to hybridize their competencies.

3. HISTORY AND POSTHISTORY

There is another Hegelian theorem under which Urbani inscribes, in the form of a gloss, a significant corollary: that of the end of history. It was Alexandre Kojève who placed this theorem at the center of his thought, wondering, not without a good dose of irony, what would be the figure of the human in the posthistorical world, once, that is, that man, having completed the historical process of humanization, had become animal again. As long as the historical process of anthropogenesis was not yet finished, art and philosophy (alongside these, Kojève also mentions play and love) certainly retained their essential civilizing function; but once - as, according to Kojève, had now occurred in the United States and was about to occur throughout the industrialized world, that process was complete, man’s return to animality could only mean the eclipse or radical transformation of those behaviors.

In 1968, on the occasion of the second edition of his Introduction to the Reading of Hegel, Kojève adds a note, in which he seems to entrust to Japanese “pure snobbery” the possibility of a singular survival of the human at the end of history. In those “summits (nowhere surpassed) of specifically Japanese snobbery that are the Nô theater, the tea ceremony or the art of bouquets,” posthistoric men have shown themselves “capable of living in function of totally formalized values, that is, completely emptied of all ’human’ content in the sense of ’historical.’”

Urbani’s legendary snobbery, which did not fail to strike anyone who knew him, has perhaps its place precisely in this absolutely serious wager: European humanity can survive the end of history only to the extent that, in a kind of snobbery pushed to the extreme power, it succeeds in making confrontation with its past its essential task. The preservation of the past, to which Urbani has dedicated his existence as a public servant, acquires in this perspective a new and unprecedented anthropological signicate, for in it depends the survival ofhomo sapiens to its history. Between an integrally animalized America and a Japan that keeps itself human only at the price of renouncing all historical content, Europe could offer the alternative of a human culture that remains so after the end of its history, confronting this same history in its totality.

The article on Vacchi (1962) collected in this volume contains decisive indications in this regard. Urbani, who may have been familiar with the first edition of Kojève’s book (1947), but certainly not with the note affixed to the second edition, begins with an unqualified prognosis of the consummation of the history of the West and the becoming nature of history: “This dense layer of unreality (call it, if you prefer, History) after a dizzying growth of a few decades, now, from clear indubitable signs, no longer grows. The rhythm of its life event has changed: the rapid succession of great thoughts and heroic deeds has been replaced by the motionless time of self-consciousness. This self-mirroring of the world of history is a solidifying, a congealing around the world of nature no longer as cultural sediment or archaeological skin, but almost as the seaweed and the shell incorporate themselves into the rock. And thus also a dying, a descending from which one returns only as a salt statue. And together, it is the beginning of an inconceivable mutation: the transformation of unreality into the real; the becoming ’nature’ of history.”

The task-or, rather, in Urbani’s less optimistic terms-the “hope” that this posthistorical situation seems to reserve as a bequest to humanity (and, in particular, to those who still practice art or reflect on it) is that “of this fatal petrifying of our history, men will one day make their own natural world; and instead of moving mountains and diverting rivers, their life, their unthinkable history may finally consist in wisely appropriating this ’nature’ of ours, in disposing of it as a raw material for their unpredictable designs”-in other words, that they, instead of wanting to dominate nature through history, first decide to confront it. And, as far as art and its history are concerned, “the part assigned to true artists is clear and precise: to fix in its indestructible membrane the ultimate meaning of what is lost, of what art ceases to be, and to impart to this solidified form of negation the energy capable of generating the next negation.”

It is only in this perspective that one understands the relentless battle that, in tones from time to time ironic or apodictic, Urbani has not ceased to fight against contemporary art: this must be criticized and taken out of the way, not because it does not have an epochal significance and task, but, on the contrary, precisely insofar as it shows itself incapable of living up to it and, “instead of freezing one by one the infinite veins of the historical body of painting, and thus consigning them to theobscure process of crystallization that will make yesterday’s history the nature of tomorrow,” s’ deludes itself that it can “reintroduce an aesthetic sap into the negation it has isolated,” seeking, with greater or lesser bad conscience, to produce “new phantasms” of works.

Against this resignation of art (which - with a courage that lends even more weight to his snobbery - he exemplifies in names that have now become venerable classics: Pollock, Fautrier, Burri), Urbani does not cease to remind artists of the urgency of their posthistorical task: “the historical consciousness of art, in the ultimate, all-encompassing and highly lucid form that is our time, has only one positive way of realizing itself: by mirroring itself. Only thus, with this increasing pressure from within, does it create the premises of its own necessary self-destruction. That is, it creates works in which the time of history has stopped, but on the hour that encompasses all the others in the quadrant, and all delivers to the duration of an infinitely recurring moment.”

This posthistorical task has, however, no other content-this is Urbani’s ultimate message-than history; the stake in it is, once again, the past: “This presentification of art-in-his-history, which began as a process of alienation with the modern availability of aesthetic feeling to ’all styles of all epochsÈ, certainly does not aim to resolve itself with the forgetting of history and with a general disinterest in past, present or future art. Rather, it will lead to knowing the essence of the historical becoming of art, namely to knowing what remains veiled today in the metaphysical concept of the formal autonomy of art. It goes without saying that the attainment of this distant goal is not the business of critics, historians or any other sort of specialists. It is the making of art that leads (thought de-) art in the right direction: crystallizing little by little in the ahistorical dimension that now belongs to it, in this closed circle that sends back to it from all sides the image of itself, where therefore it can only find itself by denying itself.”

4. CHANCE AND APPEARANCE

Not surprisingly, in this problematic context, Urbani had to fatally grapple with the issue of science and technology. A Heideggerian saying he was fond of quoting was the one taken from Hölderlin’s verse that reads, “there where danger is, there grows/ also that which saves,” which the philosopher referred precisely to technique and its decisive role in the fate of the West. The 1960 essay La parte del caso nell’arte di oggi-which is perhaps Urbani’s philosophical masterpiece-constitutes an attempt to read together, in an impervious yet stringent argument, the fate of science and technology and that of art.

The essay begins with the peremptory observation that humanity today has no other way of representing reality than as an object of scientific knowledge. Placed before things in their simple appearance, we necessarily bypass the “wall of the visible” in order to represent them objectively to ourselves according to their own requirements of weight, measure, form, physical structure. That is, reality presents itself to us already always as composed of rationally knowable “objects” and not as “things present, simply offered to view.” And what is true of reality is also true of works of art, which aesthetics has accustomed us to representing as objects endowed in turn with particular qualities and values.

It is precisely this integral objectification of the world that explains the difficulties and aporias with which art has had to contend at that crucial point in its history that coincides with the birth of the avant-garde. For from this moment on, the work of art becomes, “of all real objects, the only one that shows us a decisive laceration between its being an object... offered to our objective thought” and its being a thing solely founded on its appearance, in its “being present here, now, in such an aspect and not in another.” Caught in this laceration, the work of art tries desperately to represent itself as an object and, at the same time, to present itself as a thing.

Once again, Duchamp’s ready-made is, for Urbani, the place where this laceration was first exhibited as such. By taking any utilitarian object and suddenly introducing it into the aesthetic sphere, Duchamp forced it to present itself as a work of art and, even if only for the brief instant in which the scandal and surprise lasted, he thus succeeded “in bringing objects down from their objective horizon and provoked them to come forward as things.” According to Urbani, what happened later in the art that was contemporary for him is a kind of reversal of Duchamp’s gesture: that is, it moves from the objectively thought of work of art, as a painting made for the museum, and provokes it (through tears, stains, holes, etc.) to be the object of the museum. -again Burri and Pollock function here as implicit references) to leave the aesthetic sphere, that is, the system of formal values that define it, to present itself simply as an object among others.

Here, too, Urbani had seen far ahead. Indeed, what seems to define the art that today calls itself contemporary is the indetermination of the two symmetrical gestures: art today dwells precisely in the indifference between the object and the thing, between the object that represents itself as a work and the work that represents itself as an object. Hence the impossibility-rather, the more or less conscious renunciation of even discriminating between the two spheres: the laceration, which still defined the gestures of Duchamp and Burri, has disappeared and what now stands before us in its imperturbable indifference is merely an apathetic hybrid between the object and the thing.

It is in this context that Urbani’s meditation on art and science intersects with the problem of chance. There is, in fact, a moment when the provocations of artists for him contemporary "seem to come to a head, and the horizon of objectivity to crack, and painting to fall from the limelight of its own objective self-representation onto the bare earth of the world, to make itself a thing among things. This moment is entrusted to chance.“ And, Urbani continues, ”one does not understand what painting is trying to tell us today if one does not recognize that it speaks the language of chance."

It is in this gap, in this laceration of the work of art between its being an object and its being a thing, that the essay interrogates the growing part that chance plays not only in the gesture of action painting, but also in the shot of the photographic lens and even in the furnishing of our homes, in the technique of restoration or in theatrical direction. Chance -Writes Urbani, following, with a typically Heideggerian gesture, the etymon first of the Latin term and then of the Greek term automaton- is that which falls, which comes out of the order of causes and objectifying knowledge. It is the unobjectifiable non-value that, infinitely falling from the horizon of values and objectivity, of science and aesthetics, hopelessly seeks itself (according to the meaning of the Greek verb maomai) without ever being able to definitively find itself. Precisely for this reason, it is “the ultimate gift of the real thought objectively, that is, thought in the only dimension in which it is possible for us to think it today.” And, in this impervious situation in the no-man’s-land between science and art, between the object and the thing, its gift is for us "the last way that the real has of manifesting itself as pure and simple appearing."

Here - in this extreme deferral toward a pure appearance - Urbani really seems to move a step beyond his master Heidegger, who, when confronted with the point at which the “danger” of technique is reversed into salvation, seems to wrap himself in terminological obscurities and fall back into religious pathos. “Only a god can save us” sounds a famous Heideggerian dictum; in Urbani’s more sober terms, one could say that “only a chance can save us”-but on the condition that we do not forget that salvation does not lead us here toward the “mystery of being,” but brings us back to the vicinity of the wall of the visible, toward the pure appearance of things.

In the early 1980s, Reiner Schürmann elaborates his anarchic interpretation of Heidegger, in which, separating origin from history, he tries to demystify and grasparché as pure “coming into presence”; in the same years, Gianni Carchia, going up the history of aesthetics against the grain, identifies the supreme experience of art in the contemplation of pure appearance as such. It is singular that, many years before they proposed their revolutionary theses, this tenacious archaeologist, this relentless preserver of the past ended up anarchically leading thearché of the work of art not so much or not only back to the heart of the present, but rather to dissolve itself, beyond all time, into that pure, exhausted, smiling appearance whose access is guarded by chance.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.