The exchange of works between Italy and France for the exhibitions celebrating the 500th anniversary of the disappearances of Leonardo and Raphael (in 2019 the Da Vinci, in 2020 the Urbino) provides that twenty-one works will leave Italy for France, including those of Leonardo da Vinci and those of his other illustrious colleagues (starting with Verrocchio), while France will deprive itself of only seven works by Raphael. That there is a strong imbalance isevident not only from the numbers, but also from the form devised to frame the loans: the “Memorandum of Understanding,” that is, the agreement signed on September 24 by the culture ministers of Italy and France, Dario Franceschini and Franck Riester, in fact includes the exchange of seven works on each side, and stipulates that the others arriving from Italy appear instead as “works not covered by the Memorandum” (but nevertheless loaned by our state museums). However, this in no way changes the substance: France gets twenty-one works, Italy seven. And if the form provided that fourteen works were excluded from the Memorandum (even though they will fly exactly like the others to Paris) it is probably an indication that the imbalance in favor of France was clear from the start.

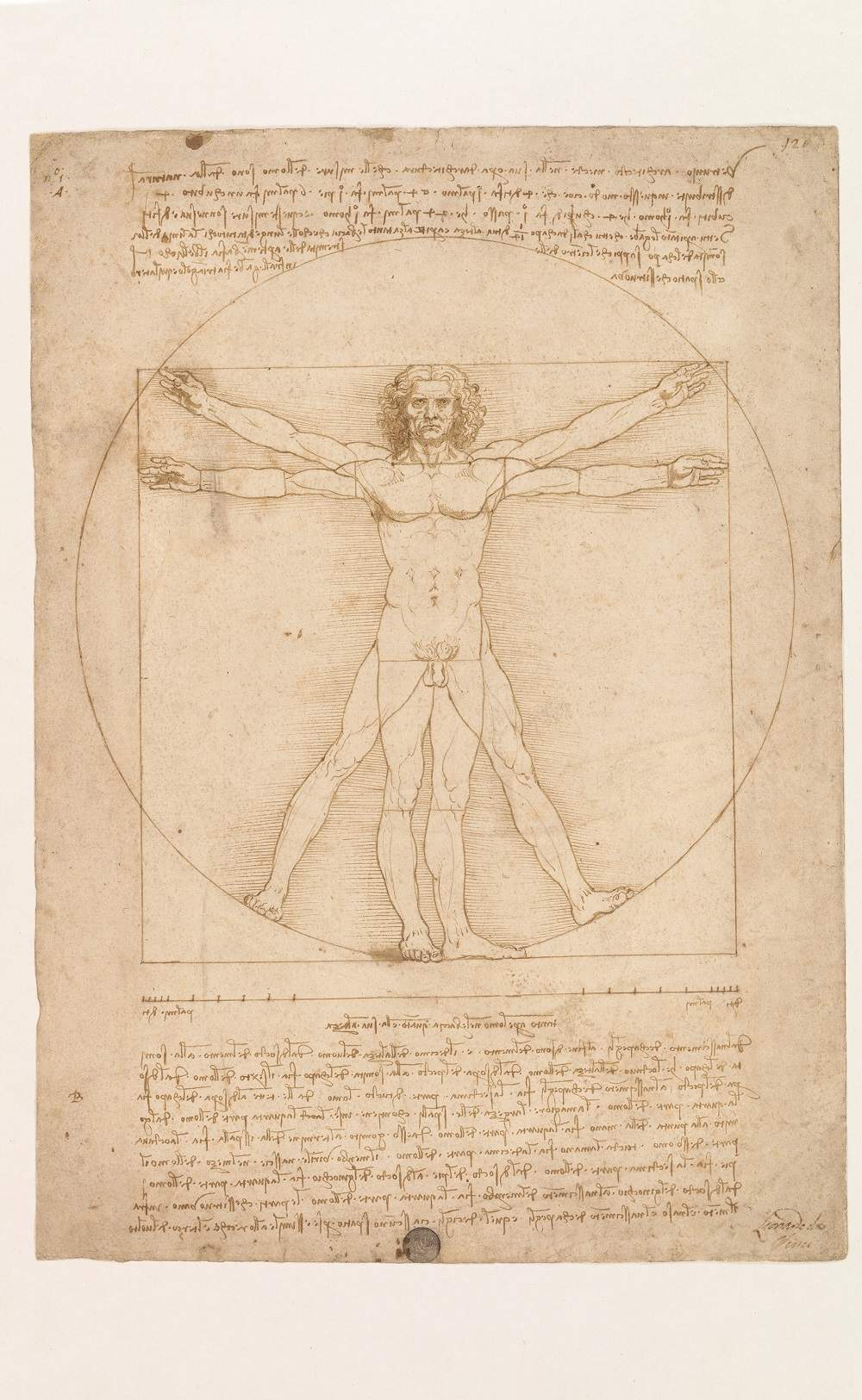

But it is not just a question of quantity: the quality of the loans is also surprising. Among the works that Italy is depriving itself of are some of the most important, and at least three of these are by the public associated with the identity of their museums (theVitruvian Man, symbol of the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, the Scapiliata, now a famous icon of the Galleria Nazionale in Parma, and Verrocchio’sIncredulity of St. Thomas, probably together with Donatello’s St. Mark the best-known work in the Orsanmichele Museum). And masterpieces include the Uffizi’s Landscape Study, Leonardo’s earliest known work, dating from 1473. France responds with two paintings ( Portrait of Baldassarre Castiglione andSelf-Portrait with a Friend) and five drawings by Raphael: to get an idea of the imbalance, think of the reaction of a potential visitor to the Pilotta or the Orsanmichele Museum who, upon visiting them, does not find the Scapiliata or theIncredulity of St. Thomas there, and then try the same exercise by imagining a hypothetical visitor to the Louvre who does not find the Portrait of Baldassarre Castiglione or Raphael’sSelf-Portrait.

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, The Proportions of the Human Body According to Vitruvius - Vitruvian Man (c. 1490; metal point, pen and ink, touches of watercolor on white paper, 34.4 x 24.5 cm; Venice, Gallerie dellAccademia) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Head of a Woman called La Scapiliata (c. 1492 - 1501; white lead with iron and cinnabar pigments, on white lead preparation containing copper, lead yellow, and tin pigments on walnut panel, 24.7 x 21 cm; Parma, Complesso Monumentale della Pilotta, Galleria Nazionale) |

|

| Andrea del Verrocchio, Incredulity of St. Thomas (1467-1483; bronze with gilding, 241 x 140 x 105 cm; Florence, Church and Museum of Orsanmichele, from the tabernacle of the University of Mercanzia) |

And that is only if we wanted to stop at political reasons, which, however, really should not be the basis for the loan of a work of art, in the most absolute way. Not least because everyone has his or her own motivations: there is no difference if you want to deny a loan because you believe that Leonardo is an Italian artist (this was the grotesque line of important players in the vast populist scene) or if instead you want to grant it to strengthen the friendship between two countries. Loans of ancient works of art should stay out of politics, because a loan is a scientific act, and not a political act. It would therefore be worth re-reading a celebrated article that Francis Haskell wrote in 1990, which was given the eloquent title Titian and the perils of international exhibition, and which the English art historian opened with a reflection on the necessary compromises on which all major international exhibitions of ancient art are based: on the one hand the lending institutions, which should grant their works only if genuine scholarly interests subsist on the other side, and on the other hand those who ask, which, however, Haskell wrote, often organize exhibitions that have nothing scientific about them, perhaps because they are set up for political reasons, for reasons of prestige or for reasons of box office. Loans, as a result, often have to conform to this logic, in the sense that they can become the object of political deals, or pawns to boost the prestige of an exhibition or its economic success. The only criteria that should guide the design of an exhibition should therefore be those of scientificity andusefulness.

It is clear and evident that the museums that will lend the works (Uffizi, Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, Complesso della Pilotta, Museo di Orsanmichele, Pinacoteca di Brera, and Musei Reali in Turin) have given their consent only after carefully verifying that the works are in a condition to travel. Just as it is glaringly obvious that the Louvre has what it takes to mount an exhibition on Leonardo that will be able to satisfy international audiences. The question must be asked, however, whether yet another exhibition on Leonardo, arranged only because a round anniversary falls this year (unfortunate: by now, it seems that art history can only be done with birthdays), and without any scientific novelties having been produced that are relevant enough to justify such a major movement of works, and this only four years after the last major exhibition (the one at the Palazzo Reale in Milan) and in the year in which, throughout Italy and beyond, we have witnessed a myriad of Leonardo events (some useful and scientifically inapposite, others less so). Not to mention the fact that, for one exhibition among many, the public could be deprived of the chance to see theVitruvian Man for a long time: colleagues at Corriere Veneto reported the opinion of the superintendent of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Marco Ciatti, according to whom further exposure of the fragile drawing could prevent it from being brought back to light for the next ten years. Not of the same opinion, on the other hand, appeared the Istituto Superiore per la Conservazione e il Restauro, but the mere fact that one of the most accredited experts on the conservation of works expressed himself in certain terms should have suggested, at the very least, the utmost prudence, avoiding a trip of dubious utility to the paper, also because this year theVitruvian Man has already enjoyed an exhaustive exhibition in its home. A problem that, on the other front, also concerns the Portrait of Baldassarre Castiglione, albeit in lesser proportions, since the work in this case does not risk forced rest, but precisely by virtue of its fragility until 2006 it had never left the Louvre: after that it traveled often, which is why it would have been the case to avoid the painting a new trip.

|