Artwork loans, Sicily far west: technicians don't decide, politicians do

Sometimes it may be conservation reasons, in other cases the lack of cultural relevance of the event, or both together. And in still a few other cases, as with the loan of Leonardo’sVitruvian Man to the Louvre, regulatory issues are raised for the stop of the transfer, in addition to those related to the work’s special conservation condition. For the Veneto Regional Administrative Court, which suspended the loan (decision postponed to Oct. 16) accepting the appeal filed by Italia Nostra, “the principle of the legal system by which public offices are distinguished into organs of direction and control on the one hand, and of implementation and management on the other” has been violated. From the Legislative Office of the Mibact retort that Minister of Cultural Heritage Dario Franceschini did nothing more than recognize decisions and acts taken by the competent technical offices of the Mibact. “In the face of scientific evaluation, which only experts can do, I stop,” the minister commented. But the issue is that the very technicians (those few still able to act independently of political pressure) have ruled otherwise. Leonardo’s drawing is included in the list of works belonging to the main fund of the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, for which, as the Code of Cultural Heritage (Legislative Decree 42/2004) states in Art. 66, c. 2, l. b, cannot be “authorized to temporarily leave the territory of the Republic.” In addition to this fundamental consideration, in the specific case there is also the negative opinion expressed, for reasons of conservation opportunity, by the official in charge of the Drawings and Prints Cabinet of the Galleries. So be it, Franceschini says to halt before the experts. That where it was possible they were duly kept away: this is what Tomaso Montanari denounces when he points out that the Ministry’s Scientific Technical Committee for Fine Arts, which he has chaired since last June, the competent committee in this case, “was kept carefully away.” And yet, in its opinion expressed at its July 24 meeting on the reorganization of the Mibact, the Higher Council for Cultural and Landscape Heritage pointed out precisely that “in the matter of loans of cultural assets of museums for exhibitions or expositions in the national territory or abroadabroad, precisely ”joint meetings of the technical-scientific committees for fine arts, for museums and for archaeology are desirable,“ in addition to ”greater coordination between the competent general directorates."

It is true, then, that if one were to appeal to Art. 67, c. 1. l. d of the Code, which provides that goods can temporarily leave the territory of the Republic “in implementation of cultural agreements with foreign museum institutions, under reciprocity and for the duration established in the same agreements,” in it, precisely, one speaks of agreements between “museum institutions,” and therefore between technical offices, and not of political agreements between states.

Now, if the measure of the Veneto Court, by stressing the interference of the political sphere in the administrative one, notes the violation of a legal principle with reference to a specific case, there is , on the other hand, a region in Italy where this interference is not only the rule, but it is a rule established precisely legally, against the Code and against the recalled principle of the legal system. We are talking about Sicily, which by virtue of its autonomy not only has exclusive competence in cultural heritage matters, but also has primary legislative power.

|

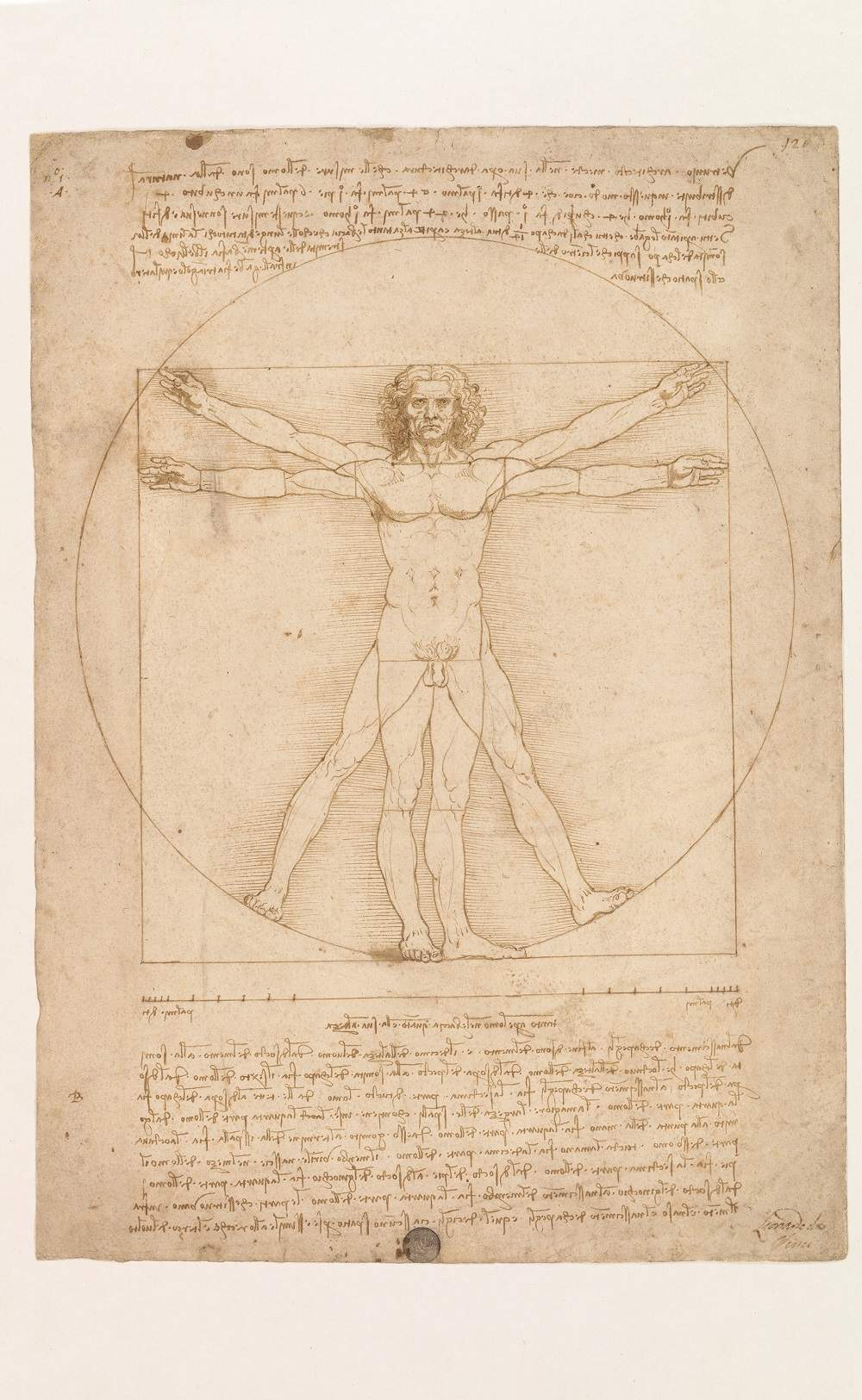

| Leonardo da Vinci, The Proportions of the Human Body According to Vitruvius - Vitruvian Man (c. 1490; metal point, pen and ink, touches of watercolor on white paper, 34.4 x 24.5 cm; Venice, Gallerie dellAccademia) |

Procedures and methods of lending works of art and goods in the Mibact: word from museum directors

But first, let’s see how lending is regulated in the state. Normative reference is Art. 48 of the Code, headed “Authorization for exhibitions and expositions,” while Art. 66, we said, regulates “temporary exit from the territory of the Republic.” To define criteria, procedures and modalities, Art. 48, c. 3, refers to the issuance of a ministerial decree. And, therefore, the Decree of December 23, 2014 (the so-called “Museums Decree”) distinguishes between the case in which authorizations are headed by the director of museums of museum poles, the director of museums or the director of autonomous museums, referring for procedures to the Decree of the President of the Council of Ministers August 29, 2014, No. 171. This stipulates that in the case of autonomous museums, it is the director who authorizes the loan after consulting the relevant Directorates General, and for that abroad, also the Directorate General of Museums (Art. 35). The director of non-autonomous museums, on the other hand, authorizes after hearing the relevant General Directorates and, for loans abroad, also the DG Museums (Art. 35). While for museum poles, it is the director who authorizes the loan of cultural goods from the collections under his or her jurisdiction for exhibitions or displays in the national territory or abroad, after consulting the relevant superintendencies and, for loans abroad, also the DG Museums (Art. 34).

These procedures were partly changed by the Bonisoli-led ministerial reorganization(Dpcm June 19, 2019, no. 76), in force since last August 22, but in fact “frozen” by Franceschini-bis. But what does it establish again? That the territorial director of museum networks (former director of the museum pole) must inform in advance the relevant superintendency and, for loans abroad, also the Secretary General, after consulting the DG Museums (Art. 34). In other words, the superintendency is no longer “heard” and thus called upon to express an opinion, but only “informed,” as is the Secretary General, who enters the scene in this area as well, confirming the criticism of excessive centralization that was intended to be given to the administrative machine with the recent reorganization. Non-autonomous museum directors must also only “inform” in advance the General Directorate ABAP, for loans abroad, and the Secretary General, while it remains that they must “hear” the Museums DG (Art. 35). The process for institutes with special autonomy remains unchanged.

In summary. One thing is clear: in no reform or pseudo-counter-reform is there any provision for the minister to replace the technical offices in authorizing loans. It is always the director who gives the okay, after hearing or informing other offices. Equally clear is the abuse that, on the other hand, takes place in Sicily, where, not only, as we shall see, is the Assessore dei Beni Culturali e dell’Identità Siciliana the one who authorizes, but even the entire Government Council is called upon to give its opinion.

|

| Antonello da Messina, Annunciation (1474; oil on panel transported on canvas, 180 x 180 cm; Syracuse, Palazzo Bellomo) |

Procedures and modalities for the loan of works of art and goods in the Assessorato BB.CC. e Identità Siciliana: word to politics

We are talking about rather recent scenarios. The issue is sensational: until last January 29, in fact, Sicily did not have a clear and unambiguous discipline for the lending of works of art. A gap in the regulatory aspect with consequent repercussions in administrative practice. So much so that one would have to wonder how loans of family jewels have been authorized over the years. We had first raised the issue in 2016 in Il Giornale dell’Arte criticizing a Sicilian exhibition on the Renaissance, where it was the pro tempore Assessore ai beni culturali who had not deemed it necessary to formalize an opinion from the director of the lending museum. The occasion for an alderman in the very branch to take notice of what we had been denouncing for years had thus, then, come last January, with a decree by the unfortunate alderman Sebastiano Tusa, with a monographic exhibition of Antonello da Messina underway in Palermo and behind the sting of controversy (and legal action) over the disputed loans.

Let us, however, take a step back. The normative text of reference even in the Autonomous Region remains the Code, but the ministerial decree in which “the criteria, procedures and modalities for the granting of authorization,” provided for in Article 48, is established, in Sicily has corresponded to the issuance of a circular (2005), which has been all but disregarded. Instead, a practice has become established that did not find, precisely, legislative footholds, whereby the loan within the Region was authorized by the museum director, while if it was outside the regional territory, the councillor, on the advice of the director and after consulting the Regional Council of Cultural Heritage (the counterpart, but with substantial differences, of the Higher Council of the Mibact).

But what, however, did that circular issued close to the entry into force of the Code say? That in the case of intra-regional loans to authorize was the general manager, after obtaining the favorable opinion of the museum director and, “where necessary,” the superintendence. In the case of loans domestically or abroad, it was mandatory to acquire the opinion of the Regional Council as well. Senonché, from 2009 to 2017, Sicily no longer reassembled this advisory body. No opinion, therefore. The point is that it was precisely the technician Tusa who determined that the authoritative opinion of the very technicians could be dispensed with, those of the highest advisory body of the President of the Region (and not of the alderman=minister, as in the Mibact) in matters of cultural heritage.

The Tusa Decree does not distinguish between “inward” and outward, the loan "shall be arranged by order of the Director General of the Department of Cultural Heritage and the I.S., after the appreciation of the Assessor of Cultural Heritage and the I.S., after hearing the opinion of the director of the lending institute and, where necessary for the sole purpose of safeguarding the state of preservation of the property, the director of the Regional Center for Design and Restoration." Translated, the technical body (DG) can initiate the procedure only after the political body has given a favorable opinion. In effect, authorization has been put back in the hands of the Assessor, when, in fact, political discretion should not interfere with technical decisions. Along with that of the Regional Council, the opinion of the body in charge of protection, the superintendency, also disappears, replaced by a technical-scientific body of the Assessor, the CRPR.

But that’s not all. The Tusa Decree also regulates the assets of the so-called "armored loan decree" (D.A. No. 1771 of June 27, 2013). It was written at the time of the dispute that arose between the Sicilian Region and some U.S. museums, to close the spigots of easy lending for a short list of 23 assets, recognized as an “essential resource of the actions of cultural heritage enhancement in Sicily.” Or so it was said at the time. In reality, it is anything but a “armored loan” regulation, doing nothing more than loosening the meshes for that very narrow list of assets identifying the region. Thanks, in fact, to an exemption (Art. 4) it shifts the evaluation of specialized issues from the technicians to the Government Council, allowing the latter full latitude, regardless of the questions of expediency raised by the former. This has already happened recently. In 2016, unusually quickly, the Junta gave a positive opinion to the loan of Antonello da Messina’sAnnunciata from the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo. Against the negative opinion of the then director of the museum, the okay was given for the loan at the turn of a dubious exhibition(Mater) of a dubious Milanese foundation, so much so that the Vatican Museums had withdrawn the works at first granted on loan to the first stage of the exhibition event in Parma, as the then director Antonio Paolucci told us. The second stage of the exhibition in Turin was eventually skipped, but from Sicily, meanwhile, the green light had been given without batting an eyelid. Thanks to the waiver provided by the decree that defers to the discretion of councillors such as those for Health, Family or Agriculture, to determine whether a fragile pictorial film can take a trip.

Of course, the Code also applies in Sicily, and primary legislative competence does not mean not being able to revise or modify contradictory norms such as this 2013 decree, already highly questionable in itself (as well as poorly written: where it indicates Article 67, instead of 66), which remained for a good six years without procedures being regulated. What seems clear, however, is that autonomy so understood has allowed Sicily to establish the primacy of politics over technical matters. If autonomy gives birth to a monster, it begets the Wild West.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.