Can a mother go against her children? Can Sotheby ’s beat a fake painting at auction for $16 million? Can the ’Italian royal family’ have accumulated works of art by breaking the relevant Italian laws? Is it possible that the superintendencies have no knowledge of the presence and state of conservation of absolute masterpieces in their territory? These are the dumbfounded questions that can be asked by viewers who watched the two-part investigation of Rai Tre’s Report program on Oct. 15 (report titled “Buy art and put it aside” lasting 38 minutes) and Oct. 22 (report titled “Treasure hunt” lasting 12 minutes) by journalists Manuele Bonaccorsi and Federico Marconi, on the collection that belonged to Gianni Agnelli, which, after his death and that of his wife Marella Caracciolo, became the object of contention between his daughter Margherita and his three children John, Lapo and Ginevra Elkann.

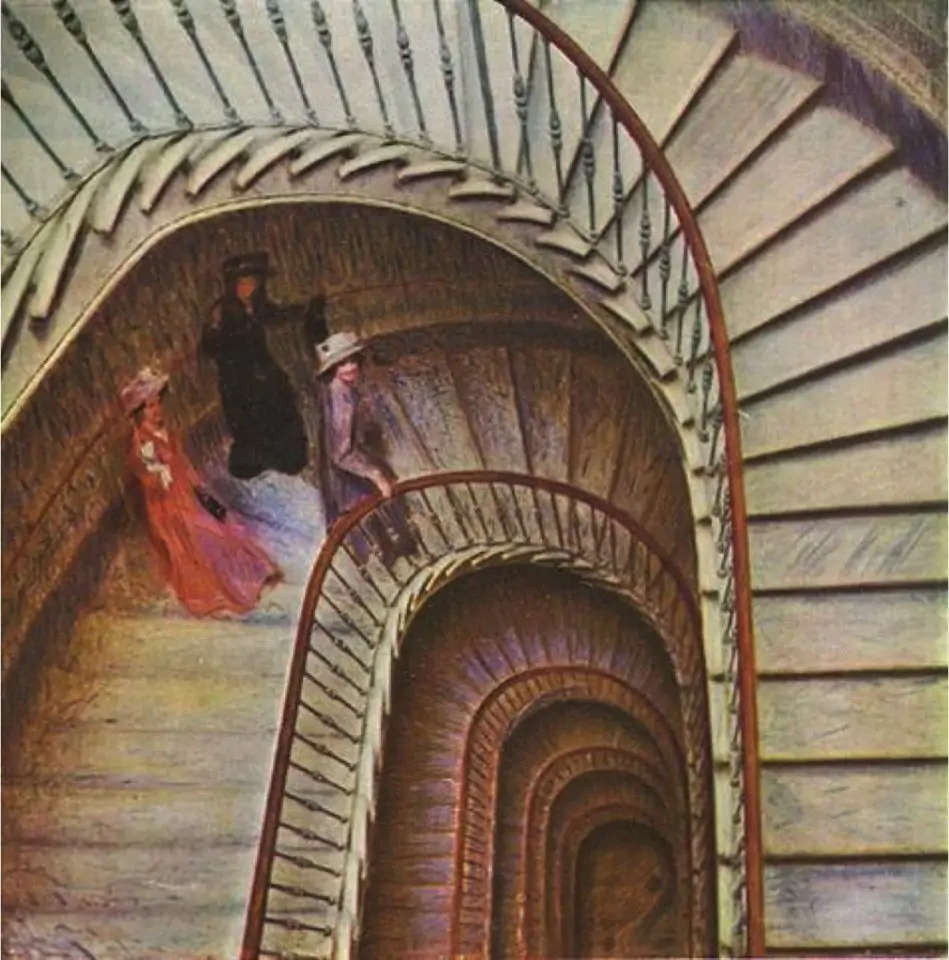

We are not talking about a “scab collector” as Silvio Berlusconi would have been, again according to Report, who on sleepless nights bought paintings at infomercials, but about a man who in the international jetset was synonymous with elegance, class, and taste, who shared with his wife a passion for art. Indeed, the lawyer allegedly amassed as many as 637 works of art from a total value estimated at 1 billion euros to furnish the rooms of his mansions. A Monet for the dining room, Picasso’sHarlequin (worth more than 100 million euros alone) in the hallway of the living room of the New York house, a De Chirico for the boys’ room, a Balla for his bedroom... Canvases, sculptures and other objects from Gianni Agnelli’s collection that once he died in 2003 passed to his wife Marella Caracciolo and daughter Margherita after a house-by-house, vault-by-vault census and cataloguing to define the consistency of the inheritance. Consistency of the inheritance, however, which Margherita, once her mother died, disputes, for not having been made aware, according to her, of all of Donna Marella’s possessions later passed on to her grandchildren. That is, her three children. And so Margherita Agnelli sued John, Lapo and Ginevra. Usual private family matters that are often repeated after a death, were it not that we are talking about a family that has been part of the history of this country and that the list includes masterpieces of modern and contemporary art that have universal value and that for this reason can be protected and restricted under a specific law, the Cultural Heritage Code, to regulate their possession, conservation, sale and possible transport abroad (which must always be authorized), and accessibility for study purposes.

After the airing of the broadcast and an interview with Undersecretary of the Ministry of Culture Vittorio Sgarbi, the process of requesting notification from the ministry to the owners for 4 canvases began. In fact, notification to the ministry would be mandatory for works of art considered worthy of protection, and even just for a change of location permission must be sought. The possibility that a work is not notified thus allows more freedom in the use of the asset and its sale even abroad, so much so that in the Rai Tre investigation an expert states that the notification on a painting would in the beginning result in the halving of its value on the market because of the limitations to which the work would be subjected. The Milan Public Prosecutor’s Office was already investigating which works would no longer be on Italian soil.

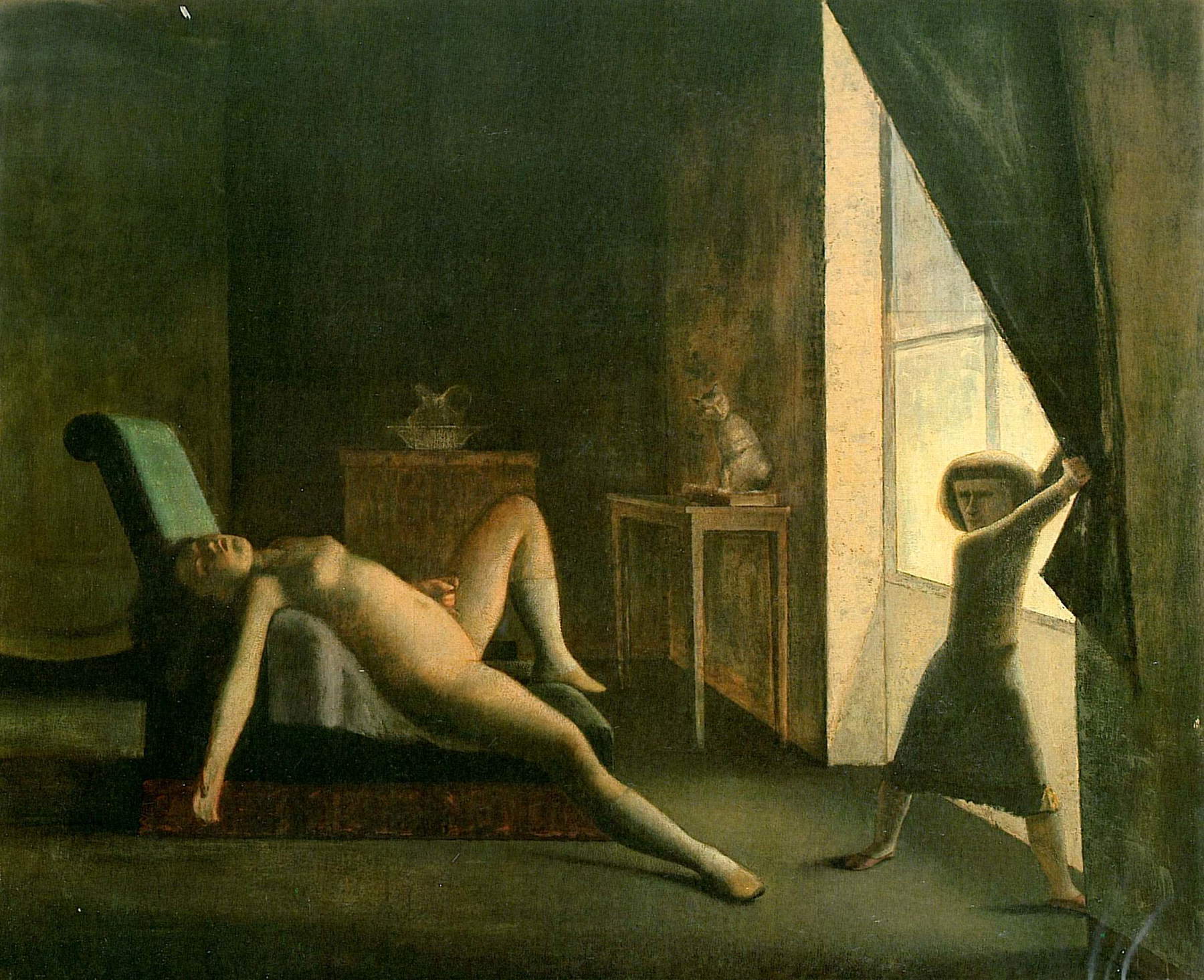

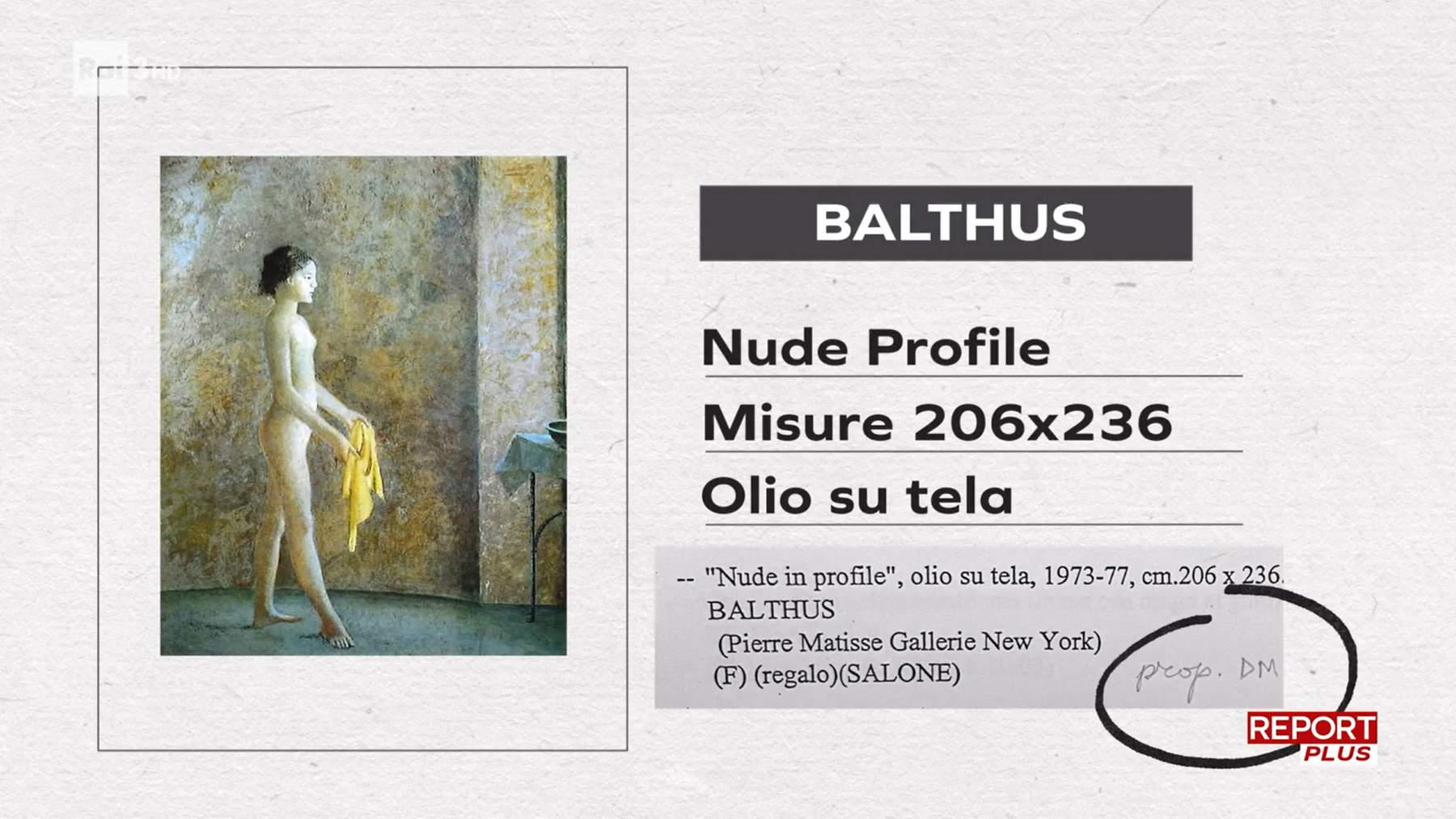

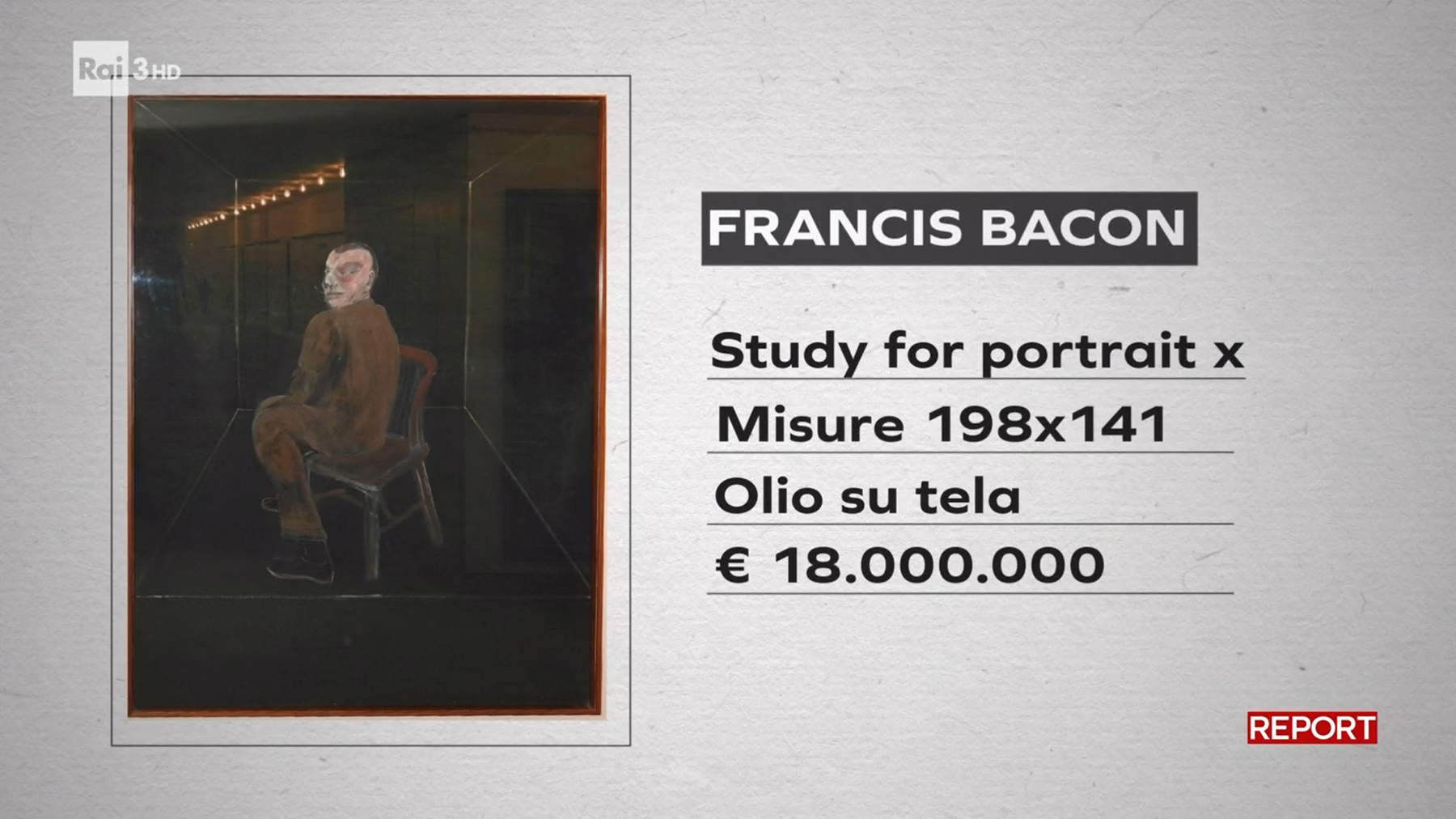

On the list reconstructed by Report and at the center of the inheritance dispute are works by Monet, Picasso, Bacon, Balthus, Klimt, Paul Klee, Schiele, Delaunay, Rothko, Francis Bacon, Pomodoro, Moreau, Canova, Bellini, Jerome, Balthus, Indiana, Matieu, Sargent, De Chirico, Vanvitelli, Balla, Schifano, Ghirri, Goya, and Andy Wahrol. Present in the Avvocato’s homes in Italy and abroad were displayed on the walls for the benefit of friends and guests. Far more than are on display in the Pinacoteca Agnelli designed by Renzo Piano (Lo Scrigno) opened in 2002 in Turin on the top floor of the Lingotto, and which the Avvocato wanted to donate to humanity, visible for those who wish (there are 25 extraordinary works).

A list about which the Ministry and Superintendencies knew almost nothing. Apparently, “No work of the Agnellis was ever notified,” Sgarbi says in the interview, and the journalist adds that “According to information from lawyers who worked with the Agnelli family, at the time of the division of the inheritance the works subject to protection in Turin would have been just four, plaster bas-reliefs by Canova, which the Agnellis kept in a sub-staircase of the Villa Frescot residence.”

Undersecretary Sgarbi, after receiving the list from Report, wrote to Margherita Agnelli, the three Elkann brothers, and the Cultural Heritage Superintendencies of Turin and Venice, to learn the location of three works, in addition to Canova’s plaster casts: these are Giacomo Balla’s Salutando, Giorgio De Chirico’s Mistero e malinconia di una strada, and Balthus’s La Chambre. “Regarding the issue,” Sgarbi writes in the letter, "represented in the episode of the Rai3 program Report on Sunday, Oct. 15, on the size of the Agnelli collection following hereditary divisions, it is proper to indicate the position of the Ministry of Culture regarding the importance of the works for the Italian artistic heritage. It is expressed through the constraint of special interest, called notification, entrusted to the discretion of the Superintendencies, which, over the years, have taken note of purchases, mainly of contemporary art, by non-Italian authors largely from the international market and preserved abroad. Upon analysis of the lists, the works purchased mainly in the 1960s and 1970s, as I tried to explain to the Report correspondents, were neither of particular importance nor more than 50 years old, which at the time was the term for establishing their historical interest. All masterpieces by foreign authors result in houses not in Italy, and could not and cannot be subjected to any constraints. Only four cases appear today, through journalistic investigation, worthy of attention and such as to activate the efforts of the Superintendencies of Venice and Turin. These are Canova’s bas-reliefs from Villa Franchetti Albrizzi in Preganziol (which should be considered ’immovable by destination’) on which an inquiry has been opened; the outcomes of which cannot, in any case, disregard knowledge of their current location. Of certain interest to the Italian artistic heritage are Giacomo Balla’s Salutando, from 1908, and Giorgio De Chirico’s Il mistero e la malinconia di una strada , from 1914. Finally, it may deserve attention, due to its presence in the exhibitions in Venice in 1980 and Rome in 2015, Balthus’s La chambre, from 1954, which is also not seventy years old and does not require free movement permits. Report’s research, with the retrieval of the lists, leads to these conclusions, for which the current owners, the heirs of Gianni and Marella Agnelli, are being asked, also through the verifications of the Superintendencies of Turin and Rome, to indicate the current location of the three works, which, according to the law, since they do not result in temporary imports or export requests, should be in Italy. For the other paintings, by non-Italian authors and not preserved in Italy, the claim of constraint and any protection by the Ministry of Culture appears nonsensical."

Amid cross-referenced documents and twists and turns (and hidden cameras unbeknownst to the unsuspecting interlocutor) Report discovers that the works on the complete list, on which the negotiations were consummated and which indicated the technical characteristics and location for each of them, appeared in the past in different places without having evidently received the Ministry’s clearance, and even one of them was allegedly sold at auction in New York by Sotheby’s for $16 million in 2013: it is Monet’s Glaçon effet blanc, one of the most important works in the Agnelli collection that he kept hanging in the dining room of Villa Frescot in Turin, but which, according to Report reports, in the papers of investigators from the Milan Public Prosecutor’s Office is allegedly in Italy in the possession of Margherita Agnelli: “On the Monet,” explains journalist Manuele Bonaccorsi, who edited the investigation, “today the Milan prosecutor’s office is investigating: hypothesis of crime of receiving stolen goods. It all stems from a complaint filed by Margherita Agnelli, who claims ownership of this and dozens of other works.” In essence, Margherita Agnelli is claiming ownership of those paintings as an inheritance, and therefore the charge of receiving stolen goods is aimed at her sons who allegedly took works of hers from her by paternal inheritance. While the position of the three children would be that those paintings were only their grandmother Marella’s and therefore not inherited by their mother upon the death of their grandfather, Gianni Agnelli.

“Report can reveal that according to a testimony in the investigation files, the Monet would still be in Italy. The one sold by Sotheby’s would be a fake. To verify this, the auction house would compare the painting owned by the Agnellis with the one sold in America. And the descendants of the patron of Fiat owned the original. We wrote to the auction house who only replied that ’Sotheby’s has investigated the matter thoroughly and is sure that all correct procedures were followed’ .” Sigfrido Ranuci wonders “how it ended up at the world’s most famous auction house” that “could beat it for $16 million? Until proven otherwise, we believe him, also because let’s remember that the illegal export of works of art that took place without the authorization of the Ministry of Culture is punishable by up to eight years in prison and 80 thousand euros fine and also the confiscation of the property.”

But that’s not all. To investigate the disappearance of the works, “Margherita hired a Swiss private investigator,” who in front of the cameras with his face disguised states that “Several dozen works of art disappeared. From the villas, from the palaces.”

Also gone is a "Giacomo Balla, the most important author of Italian Futurism. It is called the Stairway of Farewells, dated 1908. Purchased at auction in New York in 1990 for $4 million by Gianni Agnelli, it is then displayed in the Roman house, in the bedroom," and on the list there would also be another painting by Balla, very important: Old Carpenter, an oil on canvas.“ And giving the news to Elena Gigli, art historian and editor of the Giacomo Balla catalog, the reaction was one of astonishment: ”This is a nice discovery on your part. And you ask me this question because I have catalogued the painting, however, without the measurements, which I did not know at all.“ And when asked when it was last exhibited in public, he replies, ”I think only to amateurs and connoisseurs from 1904."

Ranucci in closing gives an account of the reaction of those concerned: "John, Lapo and Ginevra wrote to us that ’that our request does not hold any public interest’ and that they ’have operated in compliance with the applicable regulations and that they do not comment further because it is a matter of a private nature.’ Margherita also wrote to us through her lawyers and told us that they ’do not comment for reasons of confidentiality and security’ but emphasize that she did not object to access to the records’ requested by Report from the Mic to know which works were notified and which were no longer in Italy based on the data in the Ministry’s records. Access to the records was opposed by the Elkanns in an appeal to the Tar, arguing that these are confidential, personal and not public matters. And here we can open the debate on the boundary between private ownership and public interest of a work of art. The next hearing is scheduled for October 31.

It is worth remembering that works of art in question would be those found in three houses that belonged to the lawyer and passed in usufruct to his wife Marella upon his death: in Turin Villa Frescot and Villar Perosa and a large property in front of the Quirinale in Rome. All three of these properties were emptied and put up for sale by Margheria (according to both Report and an article in Il Foglio). According to Gianni Agnelli’s will these houses were to go “for life usufruct to my wife Marella and for bare ownership to my two children Margherita and Edoardo.”

Son Edoardo died in 2000 by committing suicide, and Margherita in 2004 decided to sign a settlement agreement on her father’s inheritance and an inheritance pact with her mother, renouncing her future inheritance in exchange for about 1.4 billion euros as revealed by Corriere della Sera in 2009. And upon her mother Marella’s death in 2019, however, once she came into possession of the three properties she had in the meantime granted for her children’s use, the long family battle is triggered. Those paintings in fact, Margherita is challenged, had been purchased by her mother Marella directly and thus by grandmother Marella’s testamentary will were intended only for the three Elkann grandchildren. In the list of “works not found,” writes the Corriere of Oct. 14, “there are paintings by Balla, De Chirico and Gérôme in Rome; Monet and two Bacons in Villar Perosa and Villa Frescot. The Elkann brothers replicate painting by painting. The Balla, de Chirico and Gérôme? The inventory of the ’goods contained in the property in Rome,’ signed by Marella and Margherita, and merged of Annex 2A of the Settlement Agreement, deliberately does not contain page 75, expunged, in which these paintings were indicated.”

Here we talked about the potentially most important Italian modern art gallery set up by private individuals, which with its hundreds of pieces would be unique in its completeness and uniqueness. Which despite being private has motivations in being protected. Here we have only given an account of the works of art but, as in the “War of the Roses,” the testamentary feud did not stop at these alone (with even ventilated threats of disclosure of the allusively hidden economic secrets) investing also other consistencies of the family’s wealth up to the holding of shares for the control of the company at the head of the Group companies. Who knows what the Advocate would have said upon seeing this hoarding.

Two anecdotes come to the writer’s mind. When a few years ago Lapo was arrested by the New York police during a night at the home of a transsexual escort simulating a kidnapping, it was 2016 (11 years after he ended up in a coma in a similar sex and drug situation), the news with all its details went around the world and in a radio broadcast they asked a historical collaborator and friend of his grandfather Gianni Agnelli, Jas Gawronski, for a comment: “The Lawyer used to say: do everything in life but remember one thing: do it with class.” Thinking instead of the relationship between the senator for life and Princess Caracciolo who are united by a passion for art so much so that they (can) spend exorbitant amounts of money on paintings such as the ones mentioned, it makes one wonder what drives a man, in this case one who has everything from money to power, to buy such valuable works by scattering them among houses and vaults that he will probably see a few hours a year. It is the taste of knowing he has them even if he does not enjoy the sight of them every day. Man, who is a desire for infinity, can never be satisfied with what he has even when he reaches certain levels. One episode is emblematic: Agnelli was able to have breakfast at Villa Frescot then take the helicopter and be in Paris for lunch and then return to Sankt Moritz for aperitifs. And one day, on one of these trips in the helicopter flying over a mountain lake he suddenly opened the hatch and jumped down into the water. When he was pulled ashore and asked why he had made such a gesture, he simply and lapidarily replied, “I wanted to feel what it felt like.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.