“I just do my job. Some people are bullfighters, some people are congressmen, I’m a photographer.” That’s how Thomas (David Hemmings) responds to an unnerved Vanessa Redgrave in Blow-Up, Michelangelo Antonioni’s 1966 film still considered an unmatched symbol of storytelling around photographic research. Her playbill stands out in one of the storefronts in Arles, a Provençal town that every summer since 1970 has hosted what is perhaps the world’s largest festival of photography, Les Rencontres de la photographie d’Arles, which opened its 54th edition to the public last June 3 and will continue through Sept. 24. That poster, albeit unintentionally, evokes one of the central themes chosen by the festival’s management: the investigation of the relationship between cinema and photography.

As old as the two arts, it is a complex bond that has developed in a profound and fascinating way, between directors who try their hand at photography and photographers who are inspired by the language of film, creating an ongoing dialogue between the two forms of expression. Antonioni - certainly - explored it more than anyone else, as witnessed also by the protagonists of his films, always engaged in the adventures of the gaze: the photographer of Blow-up (1966), the reporter of Profession: reporter (1974), the director of Identification of a woman (1982) or that of Beyond the Clouds (1995). Wim Wenders has also often related to the photographic gaze, and with Antonioni he co-directed the latter film.

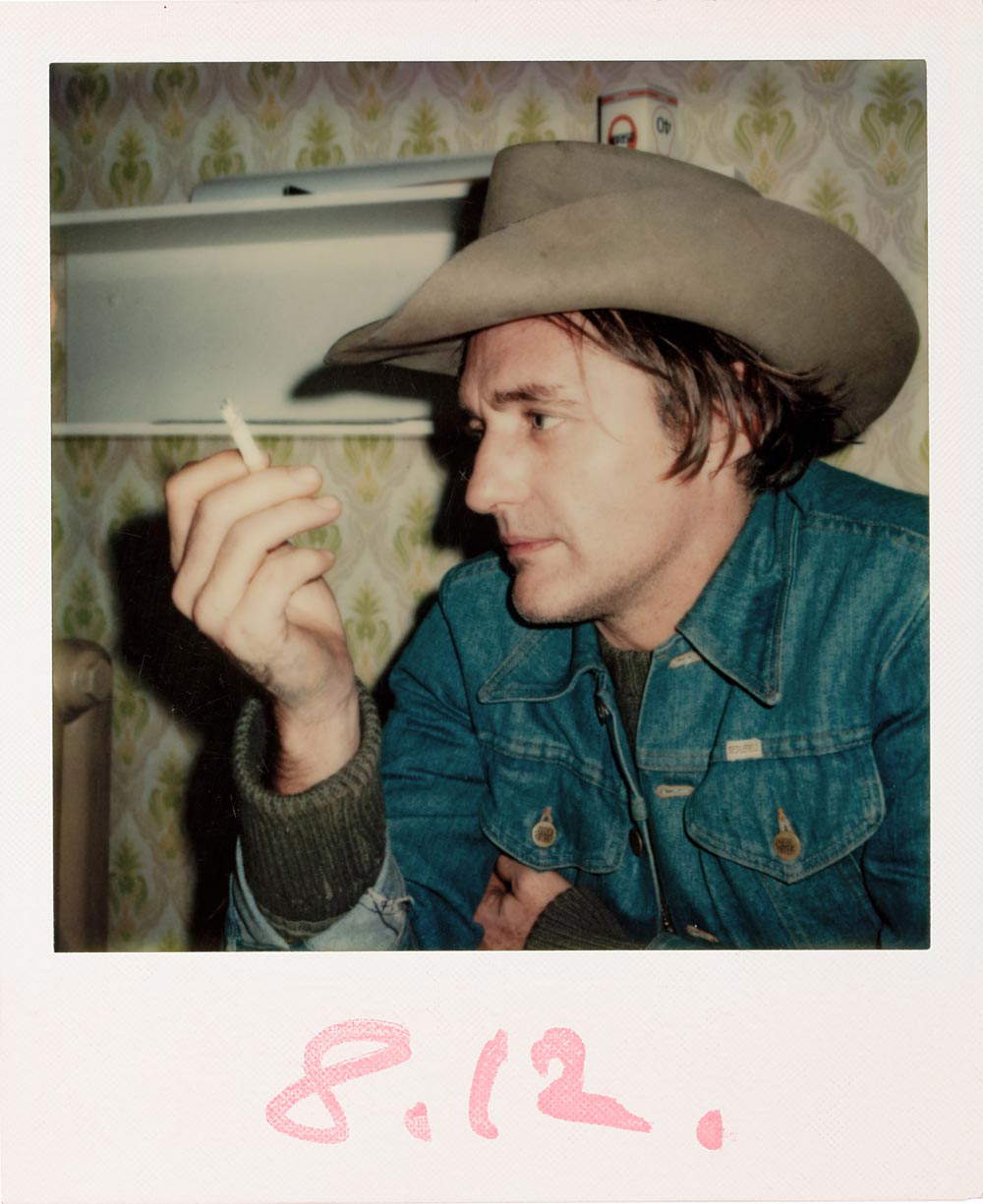

Les Rencontres d’Arles is dedicating a space to Wenders, which seems more like a tribute to the director (who was present in Arles on opening days) than an exhibition in the fullest sense of the term. In fact, My Polaroid friend atEspace Van Gogh exhibits the shots that Wenders took with a Polaroid camera, precisely, during the filming of The American Friend. The 1977 film, shot between Paris and Hamburg, stars Bruno Ganz and Dennis Hopper playing characters from Patricia Highsmith’s novel with the original title Ripley’s Game. At the time, as the director tells it, Polaroids had the function that today’s smartphone camera has: they were really a photographic notebook. With those he would photograph locations on location scouts and then stick the photos on the wall of the production office so that a record of his choices would remain. With the same camera he also photographed his actors during preparation and sometimes during scene breaks, and, at one point, the Polaroid even came to play a role in the film, which, not coincidentally, was originally, and throughout its making, titled Framed (“framed”).

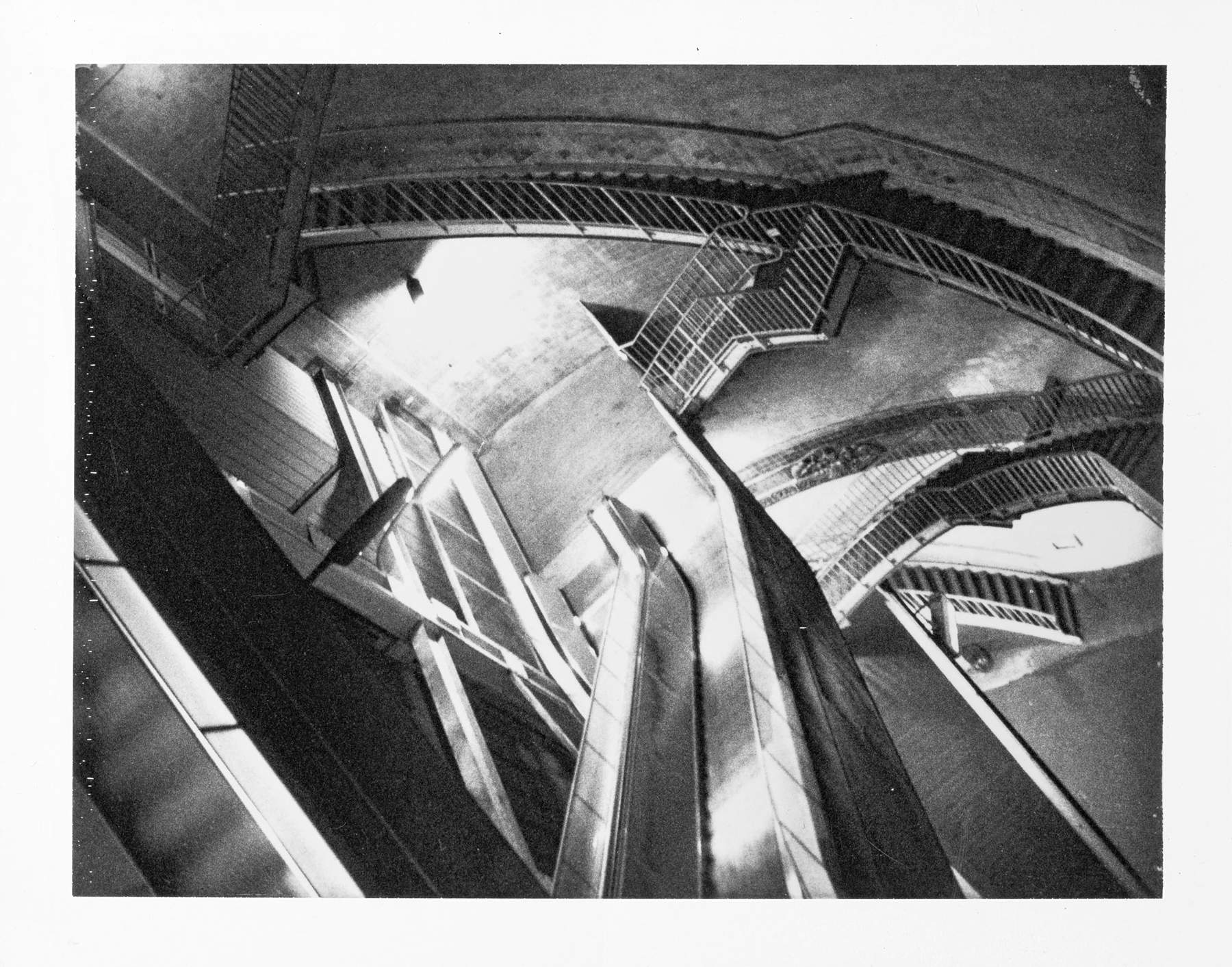

Staying with cinema, one of the best-known director-photographers is Stanley Kubrick. Before becoming a world-renowned filmmaker, Kubrick had begun his career as a photographer for Look magazine. His attention to detail, impeccable composition, and ability to capture striking images are evident in both his photographic shots and his films. And Kubrick is one of the stars of the exhibition Scrapbooks. Inside the imagination of filmmakers, also at the Espace van Gogh in Arles, which brings together the “scrapbooks,” those collections of notes that have always accompanied a filmmaker’s work in the process of building the imaginary world of a film. The exhibition explores the use of scrapbooks among filmmakers in the late 20th century, when photographic images were already easily usable and just before the digital dematerialized everything, gradually transforming the concept of the scrapbook until it became a tool for social (or “social”) dialogue.

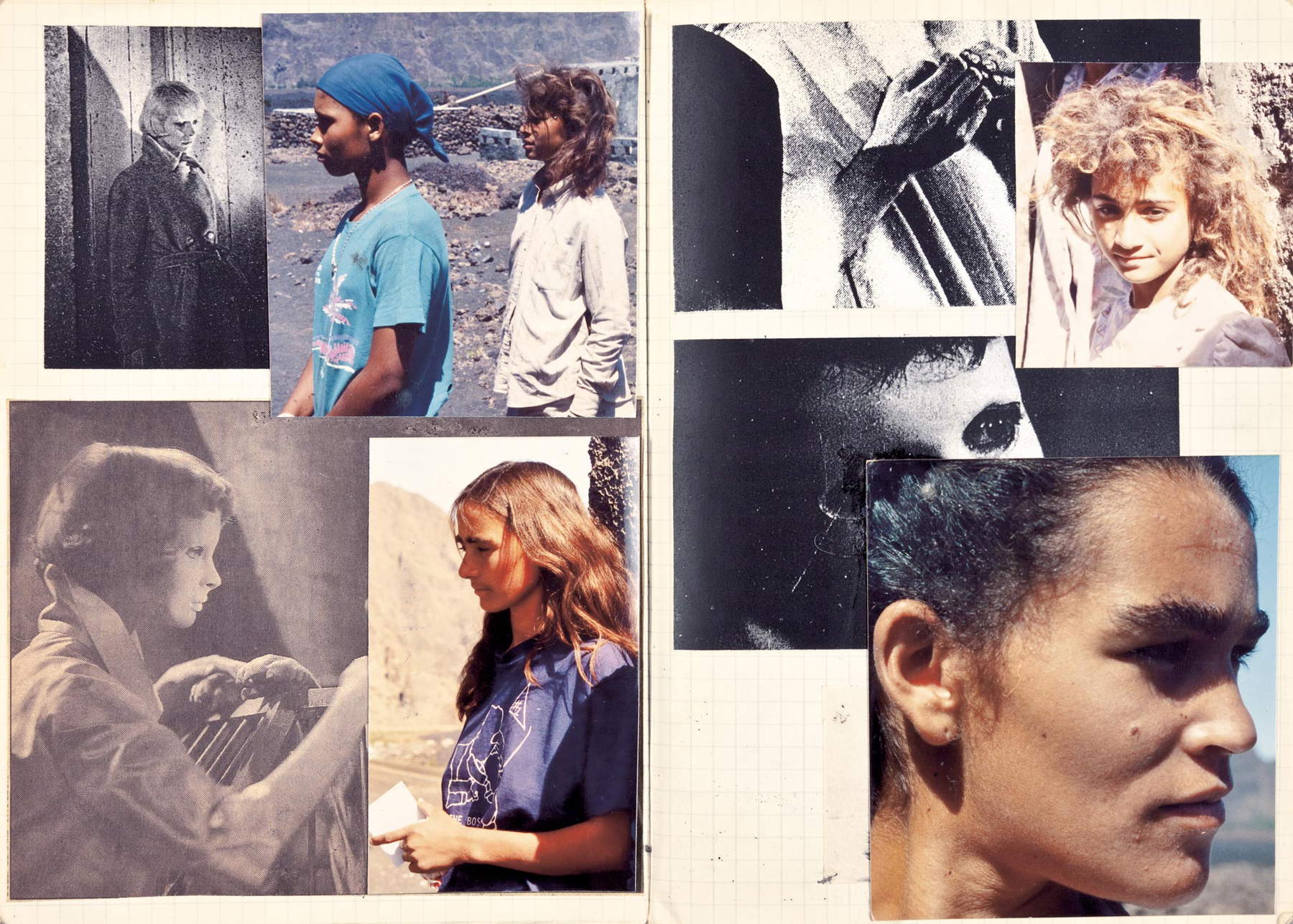

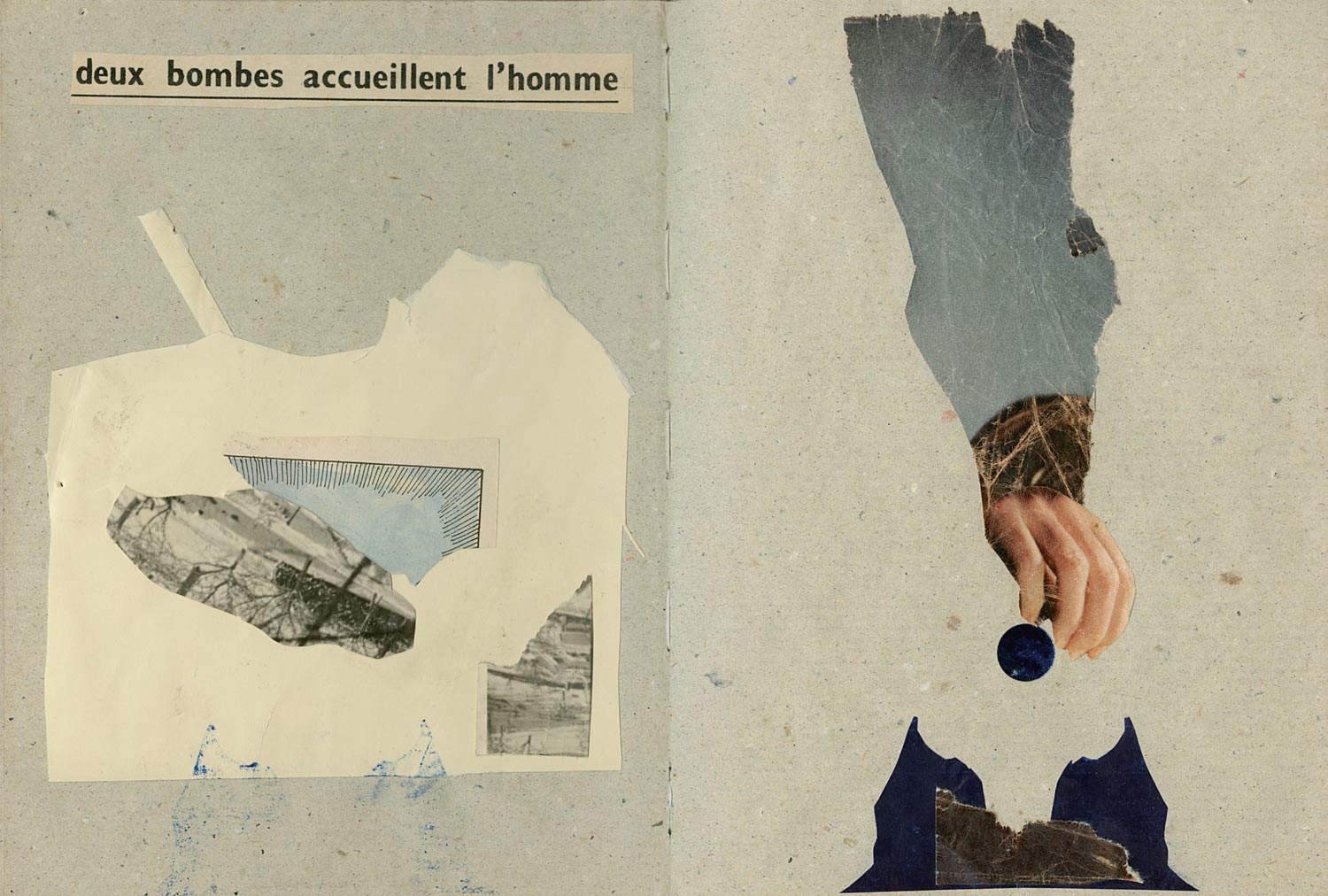

The scrapbook is a hybrid object, halfway between a notebook and a photo album that collects images from different registers: newspaper articles, photos, postcards, cut, manipulated and reassembled thus visualizing a creative process that stops in an image a path of months, if not years, of reflection and creation. From visual notes in the margins of a screenplay taken in elegant Italian notebooks ( Derek Jarman’s), to true stand-alone collections that take the form of works of art such as Jim Jarmush’s “Newsprint collages,” the scrapbook is a physical transposition of a filmmaker’s creative richness and complexity of thought. "For a film, scrapbooks are both the past (as drafts) and the future (as an archive), but also a visualization of the end result. Composed with film syntax, they offer a polyphonic autofiction in which memory follows the process of editing, not just that of a juxtaposition or collection of images," says curator Matthieu Orléan, who has collected the works of William S. Burroughs, Robert Duncan, the aforementioned Derek Jarman, Jim Jarmusch, Stanley Kubrick, Agnès Varda, among others.

Agnès Varda in particular is given a place of honor during Les Rencontres. In addition to her scrapbooks, she is the protagonist of the exhibition La pointe courte, from photographs to film at Cloître Saint-Trophime, curated by Carole Sandrin, with the collaboration of Elisa Magnani, and Agnès Varda - Hans-Ulrich Obrist Archives at Luma in Arles, which recounts the collaboration between the artist and the curator who first invited her to confront a contemporary art ostra.

A unique figure in French cinema, Varda, born in 1928, was the official photographer of the Festival d’Avignon and the Théâtre National Populaire, a documentary filmmaker, author and director. Considered among the pioneers of the Nouvelle Vague, the only woman alongside François Truffaut and Jean-Luc Godard, who came before her into the pages of film history because it was difficult to classify the complexity of her work into a single role, or more banally because they were men. "I was the first woman-author. After my medium-length film La pointe courte I was all alone in that great wave of the New Wave that followed, I was the alibi, the mistake. But I didn’t give a damn, I just made my films. Later there were the women directors of the feminist revolt. But it was a flash in the pan, I didn’t let myself get caught up in it. But I fought for women to have technical and creative roles as camera operators, set designers. So I got a reputation as an emmerdeuse feminist," she told Panorama’s Manuela Grassi in 2000. Yet, Agnes Varda was not only longer-lived than her male colleagues, but more prolific, so much so that in 2017 she still made the documentary Visages, villages that features her as a protagonist, as well as director, together with the young and innovative French artist JR. For this film she was nominated for an Oscar, making her the oldest nominee ever.

Perhaps one of the most exciting and comprehensive experiences of this year’s edition of Les Rencontres is precisely the exhibition La pointe courte, from photographs to film, which is a unique opportunity to discover Agnes Varda’s talent in the field of photography, and the construction of a process that would lead her, seamlessly, to cinema. On display is an articulated journey that starts with some of the 800 photographs Agnes Varda took in the small town of Sète, a few kilometers from Arles. Varda arrived here in 1940 as a refugee during World War II, then returned there on vacation every year until the early 1960s, and documenting (first as an amateur photographer, then as a professional) her friends, fishermen, the docks south of town, and the working-class neighborhood of Étang de Thau that soon became the protagonists of her first film, Le pointe courte, shot in 1954. Varda is known for her poetic and humane approach to storytelling, which is reflected in both her films and her photographs. Her distinctive style is characterized by an intimate attention to detail and an ability to capture fleeting moments that reveal the hidden beauty in the everyday.

Among wonderful vintage prints made by Varda herself that reveal a mature and professional photographic gaze, contact sheets (i.e., those photographs created directly from the entire strip of 35 mm negative and used primarily to select images), small prints that testify to a documentary rather than than artistic use, newspaper clippings and precious scripts full of notes, this exhibition is extremely rich and succeeds in telling the story of an incredible as well as original path of construction of a radical film, appreciated by cinephiles and critics at the time, but then cast aside by film history. An exhibition worth the trip.

If the directors who are inspired by photography are diverse, less frequented is the opposite path, which reaches its highest example with the work of Gregory Crewdson, who is not a director, but acts like one. Known for his theatrical and evocative images, he is in Arles with Gregory Crewdson Eveningside 2012 - 2022 in La Mécanique générale, an exhibition curated by Jean-Charles Vergne, previously presented at Gallerie d’Italia Turin in 2022(reviewed here). His works are characterized by elaborate sets and meticulous attention to detail, drawing attention to psychological and metaphysical aspects of the lives depicted. Crewdson creates a kind of “surreal reality” through photography, drawing inspiration from the atmospheres and narrative techniques typical of cinema.

And in the context of the broader narrative of Les Rencontres this exhibition emphasizes even more the cinematographic nature of Crewdson’s production, which for each shot builds a set entirely comparable to that of a film, in terms of the resources deployed, as well as the professionalism involved: from scene builders, to post production experts, to the protagonists of his works often played by Hollywood stars (in his previous productions he hired actresses such as Gwyneth Paltrow and Julianne Moore) .

The debate raging, among those in the industry, is over whether it is appropriate to commit these means for a single picture. Excluding the purely commercial terms, evidently already resolved by the market, I am convinced that Crewdson’s works have the power to convey all the richness of a long, cinematic narrative, in a single shot, but also to offer that multiplicity of reading planes in a temporal development that until now was only reserved for cinema. An original research path, which objectively takes away from photography its value of immediacy, of accessibility, but creates a hybrid path, and as such, a new one. And as far as I am concerned also, really, fascinating.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.