French auction house Millon makes its debut in Italy, in Cremona, with a rich sale

A debut in Italy for the French auction house Millon, which arrives in our country with its first sale, presenting, on Sept. 27 at 4:30 p.m. in the Stradivari Room of the Hotel Continental, the furnishings (paintings, furniture, carpets and objets d’art from the 15th to the 19th century) of a prestigious Cremonese mansion. The collectors at the origin of these collections were a couple of cultured art lovers from Cremona in the 1960s, a period from which the collection began to take shape (by the 1970s, the collection had already reached a very high level). With refined taste, exacting in their choices, discreet to a fault, the two Cremonese collectors represent precisely that “savoir vivre à l’italienne” that is often still made the object of envy and admiration abroad.

The heart of the sale is antique paintings, a true imaginary journey through Italy, from north to south, with some stops in northern Europe, through different styles, subjects all fascinating, works sometimes no longer admired for decades and others known only through black and white reproductions.

The main lots in the sale bear the names of artists well known to collectors, although the top lot is by a marvelous anonymous. It is a masterpiece of early 18th-century painting of popular subjects, namely the portentous anonymous painting Popolani all’aperto, recently presented in the memorable Giacomo Ceruti exhibition in Brescia (150,000 euros / 250,000 euros), among the most significant works on display at the Santa Giulia exhibition. Among the most extraordinary paintings in the history of the genre scene between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this painting has yet to see critics agree on its attribution, for the most part leaning some toward Ceruti and some toward Pietro Bellotti. The work’s historical events date back to the 1960s, when it was presented as anonymous at Relarte in Milan and immediately purchased for the rooms where it is currently displayed. Notified immediately by the state following Enos Malagutti’s attribution to Ceruti, published gradually by all the leading experts on painting in the Po Valley area (Zeri, Gregori, Frangi, Piazza), this masterpiece of naturalism, poetry and sincerity is a supreme example of that art so typically Lombard dedicated to the poorest commoners and to the medicanti from “infinite misery” (so Federico Zeri). Through the choice of an objectivity devoid of any kind of rhetorical artifice, such as to express instead the strongest and most eternal sense of the Gospel message, the anonymous (for now) painter focuses his attention on the interiorities that exude from the intense gazes of the characters in the foreground: bitterness, resentment, disappointment, resignation, fear. What daring painter could have tackled such a wretched theme in such an effective manner and on such an impressive canvas, as if it were a religious or historical subject ? And what motive must have led the unusual patron to such a choice ? The answer lies perhaps in the traditional sense of religiosity prevalent in the plains of Lombardy, where the very human and very rigorous message of Charles Borromeo (1538 - 1584) was still blended in the 17th century with the typically Lombard industriousness and sense of hospitality and charity. Archbishop of Milan from 1564 to 1584, through city processions, liturgical rites, moralization of customs and reform of the diocese, Charles Borromeo revived local faith, city and rural identities as well as social cohesion especially of the working class. The canvas can then be read as a secular manifesto of a similar moralizing work, or as a “social” memento, a source of reflection or repentance.

Continuing with the main lots, Salvator Rosa (Naples, 1615 - Rome, 1673) is superbly represented by a Bacchanal of princely size and provenance (€50,000/€60,000): the canvas dates from the artist’s Florentine period, and more precisely from the beginning of the fifth decade of the 17th century. It represents, according to Millon, “a spectacular rediscovery for the artist’s catalog, re-emerging on the market after a long period” (so in the sale catalog). Critics relate to this painting the words that Passeri dedicates in his Lives to a work that particularly attracted his attention: “He sent from Fiorenza to Rome some of his paintings that he made there for his own studio, and among others a large canvas in which he had made a Bacchanal of figures three palms high within a forest of beautiful proportion. He feigned a dense forest opaque by its thick intertwining of trunks, and branches, showing escaping in the length of an avenue, which had no end, except confused, and ill secured, and in the broadness of that an interweaving of some figures of men, women, and children dancing partly ingnude and partly covered with graceful garments and with fluttering cloaks around a simulacrum of Bacchus, and by others stretched across the ground with vases and cups in their hands partly in the act of drinking and others drunk and filthily asleep with various attitudes well comparted, and with excellent arrangement. The composition of that picture was admirable, the country well proportioned to the figures, with masterly handling of color, thinned the trees with great artifice, with admirable agreement of color, united in harmony, and if the parts had corresponded to the whole it would have been a singular picture.”

Palma il Giovane (Venice, 1548/1550 - 1628) amazes us with an immense signed altarpiece in warm lagoon colors (€40,000/€50,000). The impressive altarpiece is a rediscovery, as it re-emerges after decades to the gaze of experts and admirers: datable to c. 1610 - 1615, it is stylistically related to the St. Mark’s Altarpiece executed by Palma in 1614 (Capitular Hall of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, Venice), similar after all also in composition, and has as its model of reference Titian’sAssumption (1515 - 1518), the Venetian cornerstone of monumental religious painting : the foreshortened figure of Christ, the swirling, perspective garland of putti and clouds, the Michelangeloesque figures of the almost life-size saints, the deep shadows, the softly turned volumes, theheavenly gold of the upper part framed by the numerous heads of the cherubs, find their references in the sixteenth-century altarpiece, all harmoniously conceived thanks to the happy distribution of volumes for which Palma was so sought after, with a use of rich, brilliant color and precious, effective juxtapositions such as blue and pink.

The Early Renaissance is represented by a work by Jacopo del Sellaio (Florence, c. 1442 - 1493), a Madonna in Adoration of the Child Jesus (38,000/44.000 euros), a panel already known to scholars such as Everett Fahy, Roberto Longhi, and Federico Zeri, which takes as its reference Filippi Lippi’s altarpiece depicting theAdoration in the Woods, executed in 1459 for the chapel of the Medici Palace in Florence (now in the Gemäldegalderie in Berlin), although Jacopo reinterprets the model and creates here a new, more collected and more concise composition, which effectively responded to the devotional sentiment of Florentine patrons around 1480 (this, too, explains the success of such an image, declined by the master and his workshop in versions from time to time different: here, the elegant and Renaissance Madonna of Botticellian memory is set in a fascinating and complex landscape, lush and omnipresent, which a clear sky illuminates, while an entire herbarium welcomes the Baby Jesus, almost a hortus conclusus of Gothic memory, a Paridisian space of purity and the divine, a metaphysical place of contemplation).

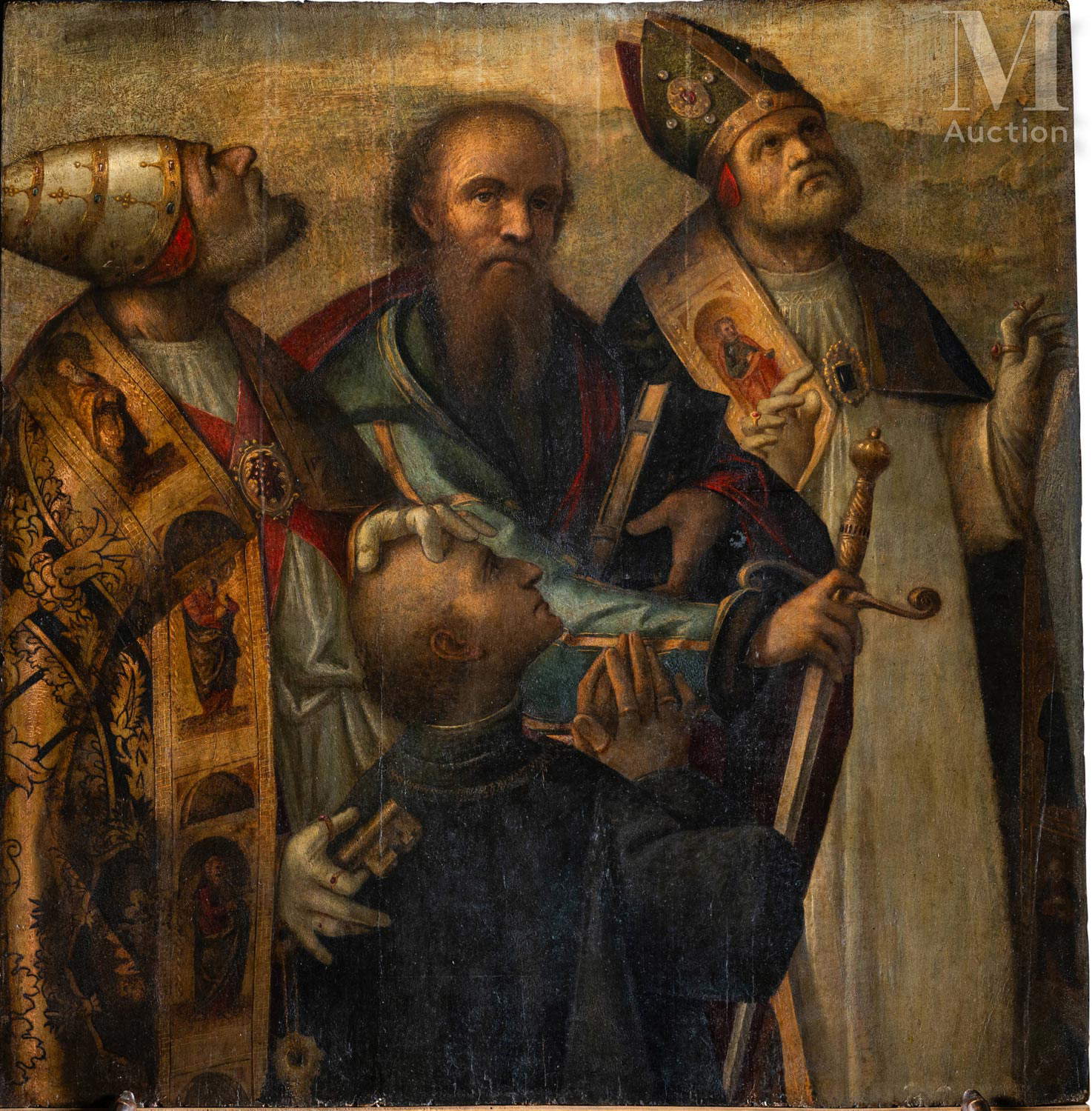

There is also a work by Boccaccio Boccaccino (Ferrara, c. 1467 - Cremona, 1525), Two Saints, a Bishop and the Portrait of the Patron (40,000/50.000 euros), related by critics (Mina Gregori, Marco Tanzi) to a document dated April 1523 (Notarial Archives of Cremona), in which Boccaccino pledged to the heirs of Benedetto Fodri to paint a large altarpiece for the high altar of the Cremonese church of San Pietro al Po. Then in 1555 Boccaccino’s altarpiece was replaced with a Nativity by Bernardino Gatti (still in situ, but on a side altar), and from that date traces of it were lost, until Gregori’s publication (1959) of the fragment presented here. According to the 1523 document, the altarpiece depicted the Virgin and Child surrounded by numerous saints and the portrait of Benedetto Fodri. For this altarpiece the painter was paid the last payment in December 1524, a year that would thus represent the date ante quem it was executed. Saved probably because it contains the alleged portrait of Benedetto Fodri, the panel thus belongs to the final period of Boccaccino’s activity, which remains among the least known and studied of the Ferrara painter. The models of the early Renaissance seem to be replaced in this phase by the humoral modes of the works of Romanino, Bembo and Melone and the material density of their brushstrokes. Gregori recalls in this regard the “chiaroscuro contrasts” the “grotesque accentuations” and “the admirable humorous lump in the profile of St. Peter, with the mitre too heavy and there about to fall.”

The Cremonese sixteenth century is represented by Giovanni Battista Trotti known as the Malosso (Cremona, 1555 - Parma, 1619), with a Madonna of the Rosary between Saints Dominic and Stephen (€12,000/16,000), which has all the stylistic and compositional characteristics of Malosso, whose signature also appears on the typical cartouche painted at the bottom, in the center of the canvas: “Malossus faciebat año 1599.” This is a very common subject in Malosso’s production and probably comes from a noble chapel. The whole composition is particularly close to two drawings referable to Trotti: one is the Madonna and Child between Two Saints preserved in the Victoria and Albert Museum, in which the position of the angels flanking the group of the Virgin and Child, here still conceived frontal and central, is taken up. The second is the Madonna and Child, Saints Lawrence and John the Baptist and the patron preserved at the Uffizi Drawings and Prints Cabinet, in which the Madonna and Child and Saint Lawrence correspond, in counterpart, to the right-hand area of our canvas, that is, to the figure of the deacon saint-not found, however, in the master’s paintings known to us-and the off-center setting of the Madonna and Jesus in the clouds. “Apex of the classic pyramidal structure,” writes scholar Raffaella Poltronieri in the entry, “the Virgin holds in her arms her son who is handing the rosary to St. Dominic, a composition already sketched in a canvas of the 1980s, the Madonna of Loreto in a private collection. But most comparable to this group is the Madonna and Child from the Courtauld Galleries (inv. 606), a squared drawing that differs from our canvas only in the absence of the rosary in the Child’s hand.”

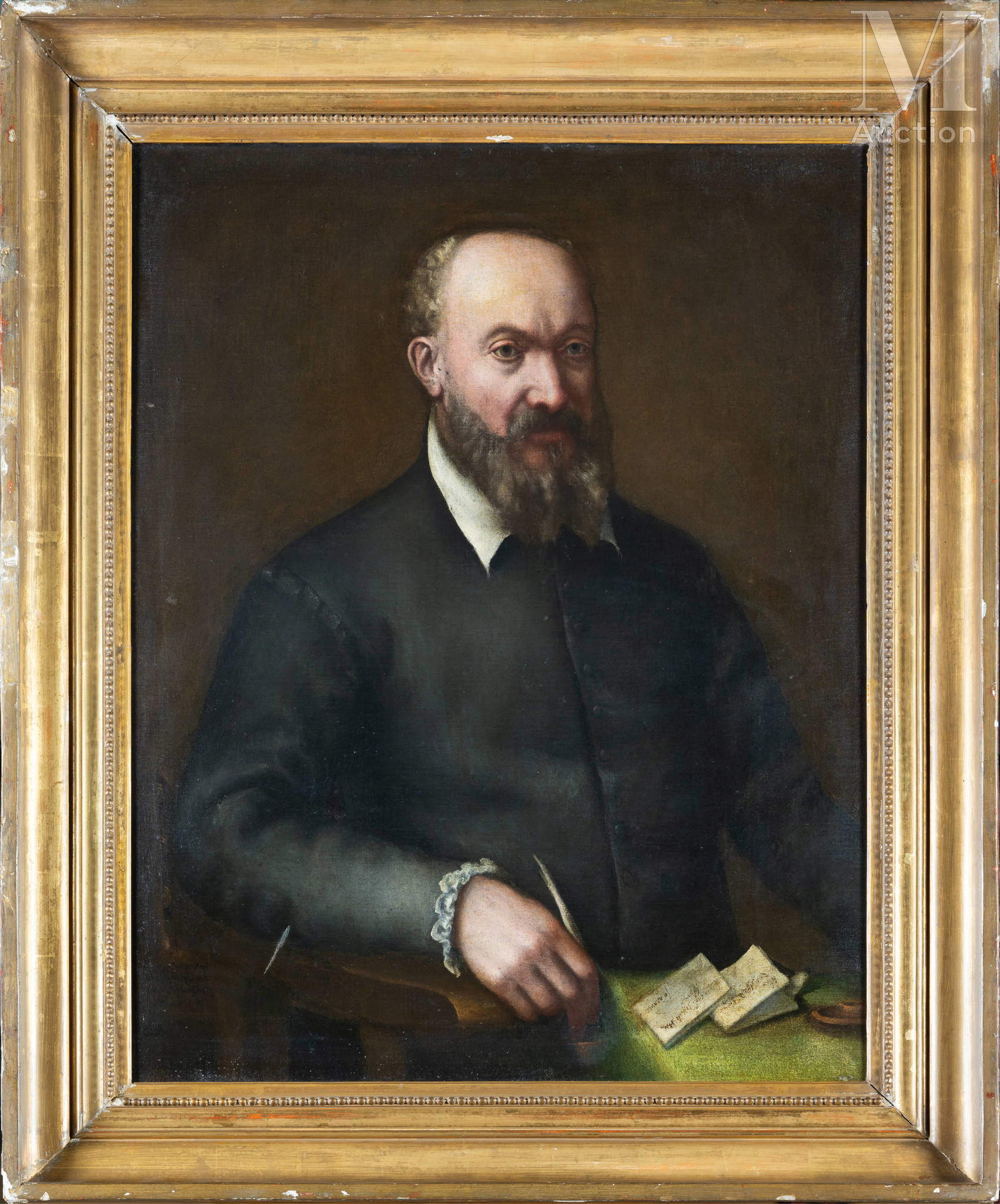

Also present is Sophonisba’s sister, Europa Anguissola (Cremona, c. 1548-1549 - ante Jan. 18, 1579) with an unpublished manly portrait authenticated for the occasion by Professor Marco Tanzi (€20,000/€30,000). “The remarkable painting,” writes Tanzi himself, "is of particular importance in 16th-century Cremonese painting because it appears to be, at the current state of research, the only one signed of the ’many portraits of gentlemen in Cremona, which are natural and beautiful at all’-mainly self-portraits-remembered first by Giorgio Vasari then by documents and printed sources, by the hand of the penultimate daughter of Amilcare Anguissola and Bianca Ponzoni. In this case the aretino cannot be faulted because the portrait is of fine distinction and rather sustained quality. Then, the finding finally comes to fill an important gap, for of Europa she was known mainly for two unexciting religious paintings, two altarpieces formerly in the church of Sant’Elena in Cremona, of which only one is signed, the Calling of Peter and Andrew now in the parish church of Vidiceto. The composition, “with the figure seated at the small table covered by the green velvet tablecloth, intent on writing a letter with a stylus,” Tanzi continues, “falls within the established tradition of town portraiture, especially by Bernardino Campi, in the mid-16th century.” The palette “is that used by all the Anguissola sisters, refined and elegant, with an accentuated taste for color contrasts that are never overemphasized but rendered with that freshness that makes each of their paintings pleasing to the viewer: from neutral backgrounds emerge the bright greens of the velvets, the blacks that turn to gray in the refined giuppone, with luminous inserts of skilful whites in the collars and snow-white cuffs; and the accentuated study of the physiognomies of the faces, amidst pales and blushes softened and lowered in tone, so as to render the effigies in their most typical expressions, of a steadfast naturalism that is never excessive. Right in the groove of Sofonisba.”

The Neapolitan Battistello Caracciolo (Naples, 1578 - 1635) is the author of a beautiful Salome , known as the “Salome Pelzer” (€50,000 / €60,000). Known to critics since Voss and Longhi, the work is dated by Causa around the beginning of the second decade of the 17th century. Battistello treated this theme in at least three other canvases (the Salome in the Uffizi in Florence, the one in the Museum of Fine Arts in Seville, and the one in a private collection), but each time in a different way, finding its starting point in the Peltzer painting. Moreover, the motif of the prisoner facing upper left would derive from the Beheading of the Baptist that Caravaggio painted in Malta in 1608, and the overall composition is certainly indebted to his Salome painted around 1609-1610 (now in the Prado). But not only Caravaggio. Citing the Peltzer painting in 1927, Longhi states, “Does not the Salomé, certainly by the young Caracciolo, as Voss also thinks, demonstrate the precedence of the Neapolitan over certain modes-for example, the contexture and illusive whiteness of the whites on the old knave’s head-that were believed to be the special preserve of Velázquez? And can the same not be said of the singular visual ’imminence’ whence that tremendous and fulminating presentation proceeds?” Resuming Testori, Causa recalls moreover that Longhi drew a drawing of his own from the Salomé Peltzer, so impressed was he by it. The Salome for sale at Millon’s thus shows signs of a strong Caravaggesque temperature, with perfect use of Merisi’s intensity in the contrasts between light and shadow and in the interpretation of the figures in terms of graphic realism.

Nordic Caravaggism is well evoked by the Card Players by Gerard Seghers (Antwerp, 1591 - 1651): probably acquired in 1960, this typical scene by the Flemish painter re-emerges on the market for the first time after about sixty years. A major player in the Antwerp art world and culture of his time, Seghers assisted Rubens in the decoration of the Jesuit Church in 1621; married Catherina Wouters in the same year; was court painter to Prince-Cardinal Ferdinand; joined the guild of St. Luke and the chamber of rhetoricians in his city; and was equally active as an art dealer. As our canvas clearly shows, Gerard Seghers’s work condenses within itself the characteristics of some of the main Caravaggesque currents contemporary to him : in addition to those of Antwerp and Utrecht, also those of Italy and Spain " (in fact, the artist stayed in Rome and at the court of King Philip III). The short, mellow brushstrokes blend admirably with the dense, piercing shadows of the scene from the typical half-figures in the foreground; the restrained but precise light creates halos and reflections as if magical, revealing and concealing at the same time, in a perhaps mischievous play of gentle ambiguity and quiet implication.

By contrast, by a rare painter, Angiolillo Arcuccio (active in Naples between 1464 and 1492), is an unpublished, impressive and remarkable polyptych on a gold ground (60,000-80,000 euros). This is a remarkably important and hitherto still completely unknown work by the painter: purchased in 1964 by Rinaldo Schreiber and kept in the following decades in the current Cremonese collection, it was made the subject of an expert report by Professor Alfredo Puerari that attributed it to an anonymous painter, nevertheless correctly approximating it to the polyptych referred by Causa and others to Arcuccio in the Neapolitan church of San Domenico Maggiore. Ignored by the scant subsequent bibliography on Arcuccio, the painting under consideration is, however, referred to Arcuccio’s hand in a photograph of only the three main panels (cardboard No. 420461) preserved in the Photographic Archive of the Kunsthistorisches Institut in Florence, where it is reported to have come from tal Boccardi in Rome and the Galleria L’Antonina, also in Rome, and has since been cited and partially published. The attribution to Arcuccio, points out art historian Pierluigi Leone De Castris, “does not present particular problems and, from the aspect of figurative culture the polyptych under examination reveals the same characteristics - proper to all the works of this painter - of strong dependence on Valencian art in Naples during the years of the reign of Alfonso of Aragon and his son Ferrante, particularly thanks to the figure of the court painter Jacomart Baço and perhaps his ’associate’ Joan Reixach.” More complex instead is the dating, placed however by De Castris around 1471.

Lots of lesser financial commitment, but no less artistic interest, include a Madonna and Child by Alceo Dossena (Cremona, 1878 - Rome, 1937) exhibited at the recent Mart exhibition in Rovereto (1,500/2,000 euros), a fine Sale of the Firstborn from the workshop of Gioacchino Assereto (8.000/14,000 euros), a 17th-century Painted Wooden Maternity (or Allegory of Charity) close to the works of Giacomo Bertesi (3,000/5,000 euros), a painting by Giacomo Francesco Cipper known as il Todeschini (Feldkirch, 1664 - Milan, 1736) depicting Three Card Players (6,000/8,000 euros). The magnificent rooms that have housed these works and the other lots included in the sale for decades will exceptionally be open to the public by appointment only.

“For its first Italian auction,” says Vittorio Preda, Millon’s ancient art expert, “Millon’s auction house and myself can only be honored to be able to present these works to other collectors and enthusiasts. These rediscoveries, which have aroused great enthusiasm in us, will certainly not fail to arouse as many emotions, comforting us in the idea that ours is the most beautiful profession in the world.” The appointment is in Cremona on September 27, 2023 at 4:30 p.m. at the Stradivari Room of the Continental Hotel, Piazza della Libertà 26, Cremona. Exhibition at the Cremona private residence from September 23 to 26 from 10:30 a.m. to 6 p.m., by appointment only by calling +33 777 999 260 or +39 338 473 5257.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.