Edith Gabrielli has been the first director since September of the new autonomous museum in Rome that unites the Vittoriano and Palazzo Venezia. These are two institutes Gabrielli knows very well, since they were part of the Polo Museale del Lazio, and the newly appointed director was at the helm of the Lazio pole for five years until she was called to direct the newly created institute. Edith Gabrielli has a long career in the ranks of the ministry (in 2010 she became MiBACT’s youngest executive) and knows very well both, as an art historian, the two museums and, as an experienced executive, the reality of public administration. We interviewed her to let her explain what the new autonomous museum will be like: from Palazzo Venezia as a museum devoted to the applied arts to a more unified Vittoriano that will also be able to count on the Ala Brasini (which will be under the aegis of MiBACT), all under the banner of a work animated by an organic vision. The interview is edited by Federico Giannini.

|

| Edith Gabrielli |

FG. The Vittoriano and Palazzo Venezia institute was officially born in December 2019, from the union of two museums that were previously part of the Polo Museale del Lazio and that were already very united anyway, not only because of their proximity, since they are opposite each other, but also because, for example, they hosted some exhibitions in common: when Minister Dario Franceschini made the announcement of the birth of this new autonomous institute he spoke of two institutes “with enormous potential.” So I would like to begin this interview by asking you what you see as these potentials and how you plan to develop them.

EG. Right to start by saying that already in the last five years, that is, under the Polo Museale, both Palazzo Venezia and the Vittoriano have experienced a phase of revitalization. Then, if you think, I can say more about the brute numbers. But much more can and must be done. The new autonomous structure allows an approach, indeed a novel and very promising vision. Let us start with the simple things, which also in this case are by no means trivial. The new institute stands exactly in the heart of the city, the capital of Italy. Later this center will be joined to the subway network thanks to the Metro C station, but already now it can be said to be well connected. Another simple thing, but again not trivial. Both Palazzo Venezia and the Vittoriano have vast exhibition areas. In the Vittoriano, I am referring to the so-called Ala Brasini, which will be managed by the new institute and which, moreover, has already in the past shown good attractiveness, also because it directly overlooks Via dei Fori Imperiali. Warning: the two institutes have very different roots, histories and identities. Attempting to suppress them or even to flatten them would be a serious mistake. The idea of connecting them should be understood as part of a larger, museologically organic project. In such a perspective, Palazzo Venezia and the Vittoriano can and should be understood as two important parts of a single whole: this whole is Piazza Venezia, currently reduced to a traffic island, but in reality itself the child of a grand project, linked to the name of the Vittoriano’s architect himself, Giuseppe Sacconi. Working synergistically on the two institutes means, in strategic terms, indicating and pursuing a common line, aimed at restoring balance, livability and legibility to a neuralgic area of our country’s capital. It then goes without saying that each institute will take on different functions, in accordance with their respective identities. Vittoriano and Palazzo Venezia, united in one institute, will tell two moments, two different aspects of the same history, which is then the history of our country. In the Vittoriano, the narrative of institutions and society will prevail, in Palazzo Venezia, art and culture will prevail. The overall idea is to make the new institute a must-see place to return to again and again.

In what ways will it be necessary to work on Palazzo Venezia?

In my opinion, everything lies in looking at the palace in organic, overall, strategic terms. I will go down to the concrete. Even today, it is customary to identify the palace with the museum inside it, the National Museum of Palazzo Venezia. Now, the museum certainly has its own value and dimension, which I will come back to immediately, but such identification results in a mistake, because in reality the museum constitutes only a part of a much larger whole, which is precisely the entire palace, a monument of truly remarkable richness and complexity. If we want to have results on the level of knowledge, dissemination and audience the whole complex must take a step forward, in fact I hope more than one. In such a vision, the museum will naturally have to change as well. You see, the National Museum of Palazzo Venezia has too often been nurtured by the ambition to assume the role of a national gallery, that is, of an institution capable of explaining, of illustrating in a complete and convincing way the entire parabola of Italian art, in ancient or modern, through a path generally framed by successive chronological phases. Apart from the fact that only in Rome there are already several such institutes (capable, moreover, of fulfilling this function much better) the nature and size of the Palazzo Venezia Museum’s collections suggest something different: its real strength lies in its ability to represent the applied arts, once thankfully far away called “minor arts.” A leading sector in several foreign museums and instead long neglected in Italy. The new itinerary of the Palazzo Venezia museum will be curved toward the materials and techniques of art: consequently, we will tend to tell that long story that from the Made-in-Italy (i.e., from the artistic and craft tradition of so many large and small centers of the peninsula) has come down to the present day, to the current Made in Italy. Both deserve an in-depth study and contextualization appropriate to their importance in the country’s history and current events. Explaining to everyone, students and adults alike, how a work of art is made, using the Italian tradition, from the Middle Ages to the present day, as a key, that is, without pre-established temporal fractures, but also with firm respect for individual moments: this is what the Museum’s new mission will be. Frankly, I think there are several elements worth reflecting on.

|

| The courtyard of Palazzo Venezia |

|

| Northern Italian artist, Hercules and Antheus (c. 1470; fresco; Rome, Palazzo Venezia, Hall of Hercules) |

|

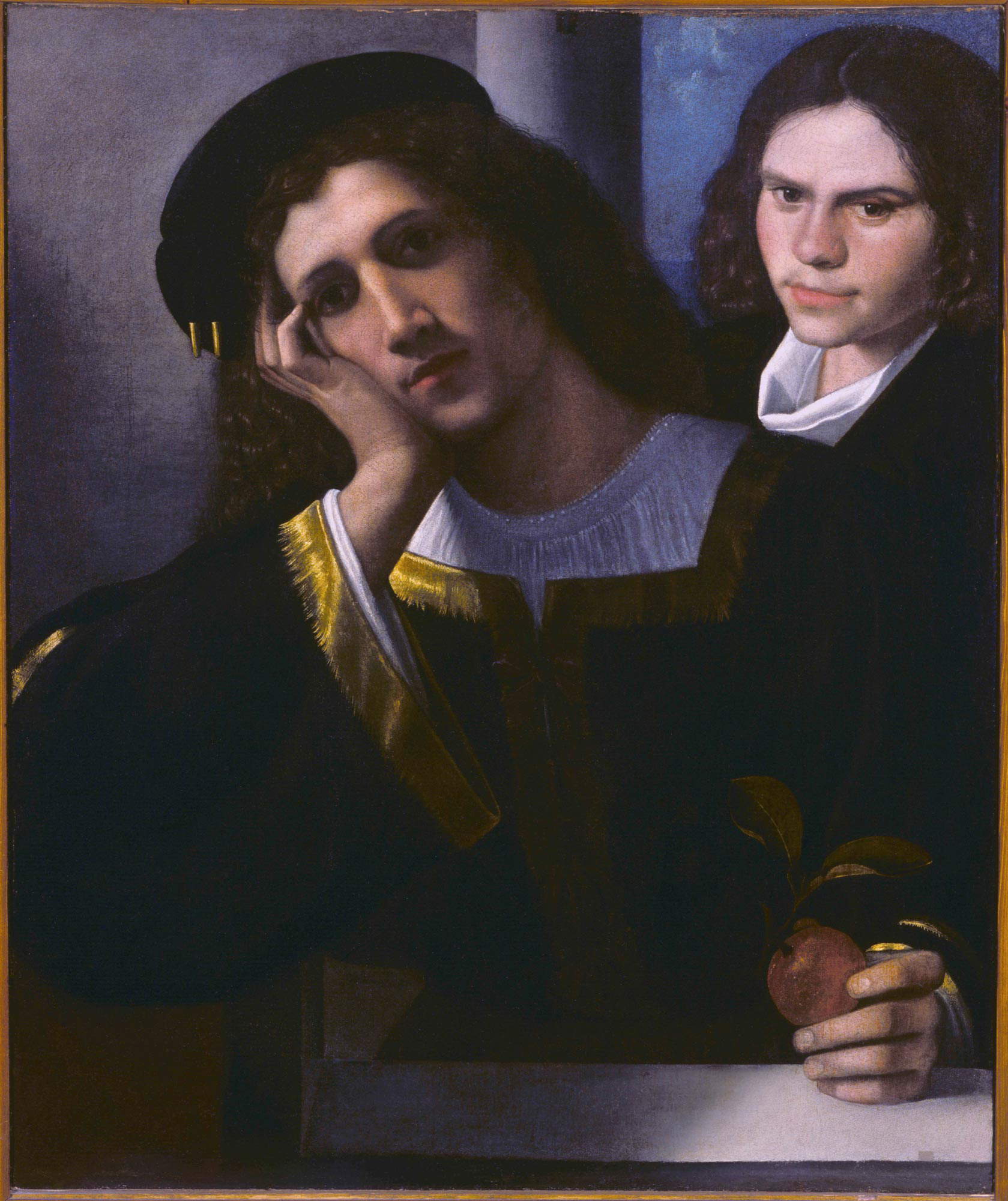

| Giorgione, Double Portrait (early 16th century; oil on canvas, 76.3 x 63.4 cm; Rome, Palazzo Venezia, Inv. 902) |

You referred earlier to the Vittoriano enhancement project, which has among its goals, if not as its main objective, to give a unified character to the monument, which for a long time has presented itself to the public with very fragmented spaces. I would ask you to give us a broad outline of this project and how it is proceeding.

The administrative conditions are now objectively more favorable. The new autonomous institute will have two-thirds of all exhibition areas under its management, including the Central Museum of the Risorgimento and, as mentioned, the Brasini Wing. But again, beware: our idea is to collaborate synergistically with the other two subjects in the Vittoriano, the Ministry of Defense and the Institute for the History of the Risorgimento. These are strong entities whose identities and expertise deserve respect. Already in the past, in the days of the Polo Museale, we worked very much in exactly that direction. With the Ministry of Defense, memoranda of understanding are already in place. We will continue to work so that the visitor can enjoy a complete and unified itinerary and therefore understand the monument in its complexity, reunifying the spaces and ensuring a single opening and closing time: visitors do not understand, indeed they hate, the fragmentation of visiting routes and the closure of spaces. Where possible, as I mentioned, I will be happy to accommodate and in turn propose joint projects. The future of the Vittoriano, I repeat, also passes through a broader and closer collaboration with both the Defense and the Institute for the History of the Risorgimento.

Despite their proximity, the numbers are very different. Referring to 2019 figures, the Vittoriano was visited by three million visitors, while Palazzo Venezia by just over fifty thousand paying visitors. Will there be a way to work then to grow the numbers of Palazzo Venezia?

Your question allows me to refer to what I was saying at the beginning, that is, to go back to the near past of the two institutes and their actual numbers, to the time of the Lazio Museum Pole. Let me then state that not only one, but both monuments have gone through a distinctly positive trend. Let us start with the brute numbers. In 2014, the Vittoriano had less than a million spectators: at the end of 2019, more than three million. On Palazzo Venezia we must make, as I said before, a distinction between museum and palace. In 2014 the palace, except for a few and certain occasions, was closed to the public. As for the Museum, it had less than 9,000 paying visitors. Five years later, the reopening of Palazzo Venezia saw half a million spectators flow into the courtyard and adjoining spaces. This flow has certainly helped to improve the museum’s performance, which in 2019 recorded more than 20,000 paying visitors. There is more. The palace’s garden itself, the lower loggia, the upper loggia, and other spaces have hosted a fair number of cultural initiatives and events, in this case for a fee and mostly included in a museological project called ArtCity, organized from 2017 to 2019. In this way, Palazzo Venezia has made an important contribution to reaching one million users in the summer of 2019. Frankly, I judge this to be a good result already, but again, we can and will do more. You see, for various reasons, some of which I have already outlined, the National Museum of Palazzo Venezia has proved in history to be incapable of developing a strong and constant attraction. That is why it will be necessary to intervene, and in depth. But the change will also be linked to the context, that is, the palace itself, which in turn has changed, is changing and will change even more. Those living around have already noticed this, and how much. That is why I have great confidence in Palazzo Venezia. It is an extraordinary building in many ways. It just needs care and especially to be well told, well communicated. The palace, its courtyard, its green spaces have become a busy place, a shelter from traffic. They work, again. And when they work well for those who know them, for those who live or work next to them, it means you are on the right track.

Let’s talk about exhibitions: we mentioned earlier that in the past Palazzo Venezia and the Vittoriano have been the scene of important exhibitions, Voglia d’Italia on late 19th century collectingcomes to mind, for example . What is under consideration for what concerns the exhibition activity of the institute, especially since now the Vittoriano will be able to count on the Ala Brasini?

Voglia d’Italia has been many things. Among other things, it helped bring attention back to a period of our country that was for too long and unjustly neglected. From the standpoint of museology, the exhibition can also be read as a kind of dress rehearsal, in view of the unified conception of the two monuments. It is worth remembering that it was divided into two sections, one in Palazzo Venezia, the other in the Vittoriano. On that occasion the architect Benedetta Tagliabue and I also studied how to make the visitor walk along the road separating the two monuments precisely to give the idea of a path. Not only Voglia d’Italia, but practically all the exhibitions we have done in the Pole have been characterized by a very precise suture line between scientific quality, didactic and popularizing commitment (i.e., care in conveying in a simple and clear way the results of research) and finally the ability to attract the general public. I still think exactly the same way. But you rightly ask me about the today and tomorrow of the Vittoriano and Palazzo Venezia. I’ll get to that right away. To do so, it is necessary to insist a little on the concept of a program. You see, if we talk about a single exhibition everything may seem relatively simple. But one swallow does not make a summer, or at least not always. The hard part comes right after that. That is to continue along the right path. To do that planning becomes essential. Exactly why we are thinking, or rather have already thought, about medium- and long-term programming. The plan is to have exhibitions of different levels and approaches, so large exhibitions of strong commitment but also exhibitions of medium and small proportions, with which to investigate circumscribed yet equally interesting phenomena, so as to have a place where the programming finds its own continuity. On the individual exhibitions, now. I would like to repeat, the ridgeline will remain the same: we will do exhibitions that can hold together research, didactics and the ability to arouse interest. Those who know me know that I am a great supporter of Italian methodological reflection in the field of cultural heritage: I believe there are some concepts in which our country has made an enormous contribution to international reflection. Let us suffice here the concept of territorial protection or that of planned conservation. All this, however, does not exclude communication and also the ability to be really serious in planning, that is, for example, to discard those ideas that, however valid on a theoretical level, in reality for various reasons would fail to capture public interest. At the exact opposite end of the spectrum, we need to evaluate with extreme rigor and if necessary shelve those proposals that, although they may make the sirens of economic convenience sing, do not have the necessary scientific requirements. To all this I add a third plan, which is that of education. We can really make an impact as cultural institutions only if we work on this. This is one of the things I am working on most at this stage of planning and programming. If we succeed in this, we can really contribute to the revitalization of Rome as a capital city where one comes not only once in a lifetime to see the must-see monuments, but also where one must return because it is a promoter of cultural activity that deserves to be discovered every time.

|

| View of the Vittoriano |

|

| The Vittoriano |

Precisely on this aspect, another point to which you have turned your attention during your tenure at the Polo Museale del Lazio is represented by the activities aimed at the younger public, that of children and young people. In relation to them, how will the institution position itself and what are the activities you will have the opportunity to work on?

I thank you for the recognition. In fact in the days of the Museum Pole we did a lot in this direction. I only recall the engagement with the many thousands of high school students involved through the School-Work Alternation project. But let us come to today and tomorrow. The new institute has on its side a significant relevance on the historical-artistic level. It is also true that when dealing with the Vittoriano one must keep in mind a strong institutional value. That is also why, when we talk about art and heritage education, we do it as a form, and among the highest, of citizenship education. We are working on the various audiences. Right to think that education is primarily aimed at children and young people. I said primarily, not solely. We also need to go beyond that. I am thinking, for example, of second-generation Italians, that is, the so-called ’new Italians.’ We have thought a lot about this already under the Lazio Museum Pole. Italian Lexicon. Faces and Stories of Our Country was an important exhibition in this respect. Curated by me personally for the museological part, but with a team of psychologists and philosophers of language at its side, Lessico italiano was an important step in focusing in exhibition terms on the mechanisms of our identity and, at the same time, communicating them in terms as positive as they are current to today’s citizens. Let us then take the concrete example of Palazzo Venezia and its museum, just as we want to change it into a museum curved around applied arts, that is, the materials and techniques of the arts. Well: all of this comes through a strong educational effort for me. I remain convinced that a large part of the public and almost all school-age children do not know how a fresco, a panel, a wooden sculpture, to say nothing of a seal or a sword were produced. So how to convey all this to them? The intention is to work on two levels. The first level can be enjoyed remotely: we will make available to the public, through our website, downloadable materials, such as to prepare for the visit and that is to delve into it afterwards, once it has been made. A second level is in-presence: we will study specific activities, including workshops, so as to concretely explain how individual works are created, through their respective working techniques. It should not be forgotten that art also comes from a practice, a craft, an awareness. Beware here: the material and technical aspect represents a bridge, one among many possible ones, to access art and its linguistic aspects. I believe that such an approach can prove successful on the educational level: many viewers ask us for it, sometimes under the impetus of the restoration experience.

And speaking of remote activities, good work has also been done on digital in recent times on the Vittoriano, because the Vittoriano has a site that has a lot of content and is also very much appreciated not only by the public but also by communication professionals. How will the new institute intend to communicate through digital tools?

You rightly mentioned that the Victorian was given a new official website just under a couple of years ago, in June 2019. Well: that site earned an honorable mention at the Webby Awards, which for those in the industry are equivalent to the Academy Awards for movies or the Grammys for music. Let me also mention the application, or app, that is downloadable from and related to the site. You see, the Vittoriano app, in addition to being very innovative, is designed to achieve a result that is not at all obvious, to guide the visitor according to a path, so that he or she does not miss anything, and at the same time avoid making him or her feel in a cage, an effect that is particularly undesirable for everyone and even more so for young people. We will continue to work in this direction. The new institute will, of course, need its own site, which in part will take up the positive experience of the Vittoriano. The Vittoriano and Palazzo Venezia website will provide quick and intuitive access to pages about the various institutes that comprise it, including the Library of Archaeology and Art History. On this I would like to open a parenthesis. As is well known, the Library, known by all as BIASA, is destined to move to another location: a truly remarkable project, which will certainly contribute to its revitalization, long awaited by its users. On the other hand, at least as long as it remains inside Palazzo Venezia we intend to work positively with it, precisely because we consider it a fundamental resource for scholars and students. Its ’strong’ presence in the new site goes in this exact direction. To return to the main question, which is whether and how much we want to do in digital, we are planning an app for Palazzo Venezia as well, and an extremely rich content offering. The idea is to organize an editorial staff, capable of making content available to the public remotely as well. Digital will also be useful, as I said, within the educational workshops and tour routes. I’m thinking of its potential in telling the story of individual buildings and also of the surrounding area: the project submitted to the international selection plans to allocate the underground spaces of the monuments that will be connected through the Metro C station to the entire urban fabric of Piazza Venezia. Of course, all this provided that digital is used properly. Pandemic has taught and is teaching us this as well. I say ’properly used’ where, in my opinion and without taking anything away from those who have thought otherwise, digital should flank, never replace the real visit: at the center of our museums must remain the living, direct experience of the objects.

I latch on to this last reflection on the relationship with the territory to close the interview with a question that relates to this very topic: an issue that has become on the agenda with the covid emergency, since it is said that museums will have to work a lot with the territory, much more than before. As director of the Polo Museale del Lazio You, in addition to having obviously already worked with Palazzo Venezia and the Vittoriano, have also worked a lot on local communities, since the pole summed up several museums especially from the territory. In this sense, how should the new institute work in your opinion?

The experience of Covid-19 leaves a very significant datum: when we reopened in May, the museums in the big cities (I am talking especially about the museums in Rome) had a vertical collapse in visits, while the museums in the territory in some cases recorded an increase in visitors, in some cases on the order of 20-25 percent. The explanation? Covid has produced an increase in so-called proximity tourism, that is, made up of people from other municipalities or regions of Italy. Little has been said about this, perhaps because priorities were other, yet it does not seem to me to be a negligible figure. You see, in my experience in contact with the territory, first in Piedmont, then in Latium, I have often heard local administrations invoke the ambition to great international tourism. In some circumscribed and determined cases this ambition has been translated into reality. Most of the time, however, it has been a dream, a myth. What remains is the collaboration between those who run large museums, such as precisely the state, and individual local communities, to the point of creating a relationship of real, direct and constructive synergy. The ultimate goal is to make that monument part of the territory. Or, taking the opposite route, but to achieve the same result, to convince the citizens of small and large municipalities that that palace, that park, that villa, that archaeological area are first and foremost part of their respective identities. That the first ones who have to appropriate it, who have to experience it, are them. It is not always easy, it depends on many things, but in my opinion this was and remains the only serious way forward. My album as Superintendent of Piedmont and as Director of the Lazio Museum Pole abounds with such experiences. One suffices for all. In 2015 several among the museums and cultural places given to the Polo for management were closed, sometimes for many years. To recall them all is not useful, but I assure you that there were at least 10 of them. These included the so-called Tower of Cicero in the upper part of Arpino, near Frosinone. The mayor of the Lazio town came to see me and together we decided that the time had come to reopen it. I repeat: together. Sometimes all it really takes is a little goodwill on both sides. The opening ceremony was held at the same time as the Certamen, the well-known Latin translation competition that takes place exactly there every year, at Cicero’s birthplace and which gathers the cream of tomorrow’s classical philologists. I myself had been among them, in my senior year. Well: seeing the lawn surrounding the tower packed with the citizens of Arpino and together with these four hundred or so young people, from all over Europe, remains in my personal scrapbook of memories. This talk can also fit in the post-Covid period, hopefully as near as ever. I would not be at all surprised if the first movement of affection toward our museums came from there, from the people and community who are close to them. Something similar also marks the project on the new institute. In this project, as I said, a part of the museum will also be allocated to tell the context, the square, the place, because these two monuments should really be read within the urban fabric. Moreover, if there is one thing that the 2001 Policy Act made clear, it is that Italian museums have one more mission than others: connection with the territory. This connection with the territory is quite palpable when it comes to museums and archaeological areas that are located in suburban settings, but it is also so in large cities: even large museums in order to function at their best need to establish relationships with the fabric that surrounds them. That is why my first thought in clearing the courtyard of Palazzo Venezia of cars was precisely for those who live in and frequent this area.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.