Vercelli, an exhibition to discover the medieval city and all its secrets

In medieval times Vercelli was one of the most prosperous and important cities in Italy in all aspects, from economic and commercial to religious, as well as social and cultural. Indeed, history speaks through the documents that have come down to us, but also through artistic and architectural works. Indeed, the city’s main churches and great treasures preserved in local libraries and archives date back to this flourishing period. And of course, history tells of facts and personalities: among the most relevant protagonists of the immediately premedieval Vercelli is certainly St. Eusebius (4th century) to whom we owe the spread of religion throughout the territory of today’s Piedmont and in particular in the Vercelli area, so much so that the city became one of the most impressive dioceses in Italy and an episcopal seat. In fact, the city’s cathedral is named after the first bishop and patron saint of Vercelli and Piedmont, which houses the saint’s remains in one of its chapels: built where an early Christian basilica once stood, it was completely rebuilt in the second half of the 16th century and then remodeled between the 18th and 19th centuries; the only survivor from the Romanesque period is the bell tower. The cathedral also houses, in the center of the nave, one of the symbols of the prosperity of the diocese of Vercelli, namely the Ottonian Crucifix, commissioned by Bishop Leo of Vercelli: made in the early year one thousand in embossed and partly gilded silver foil, the Christ depicted on the Christus triumphans type bears a rich crown decorated with precious stones.

To learn about medieval Vercelli, it is therefore necessary to rely on the city itself to discover the evidence of that past, both by visiting places associated with that era and through archival materials that preserve and open up collective historical memory. An exhibition running until June 27, 2021 at the Arca exhibition center, titled The Secrets of Medieval Vercelli, intends to take visitors on a kind of journey, also immersive and emotional, within everything related to the Middle Ages in Vercelli. An exceptional guide who accompanies the public through various videos present in all sections of the exhibition is Alessandro Barbero, medieval historian and lecturer at the University of Eastern Piedmont: academic descriptions will prove useful for a deeper and clearer understanding of the precious works and important documents from the city’s most significant institutions displayed along the tour route. The latter unravels from the 9th to the 14th century, the most intense and flourishing period for Vercelli, following a plurality of voices: not only the most famous documents, but also the seemingly more modest testimonies. Knowing the vicissitudes of the diocese and the Commune, the University (Vercelli established the first University of Studies in Piedmont) and the great urban aristocratic families, one has the opportunity to understand various aspects of the society of the time, from the organization of power to the forms of daily life, from political and religious ideologies to cultural developments.

|

| The basilica of St. Andrew in Vercelli. Photo by Luca Volpi |

|

| Vercelli Book (Second half of 10th century; parchment and leather binding on 18th-century wooden boards, 325 x 220 mm, southeastern England; Vercelli, Metropolitan Chapter of the Cathedral of SantEusebio Vercelli, Chapter Library, ms CXVII) |

|

| Ottonian crucifix (10th century; embossed and partly gilded silver foils on wood, 327 x 236 cm; Vercelli, Museo del Tesoro del Duomo) |

From the outset, the exhibition immerses visitors in the Middle Ages thanks to an 18th-century engraving from the Agnesian Diocesan Library that depicts the profile of turreted Vercelli, a sign of power and active life. Particular emphasis is placed on the Ottonian period, the period when emperors of the Holy Roman Empire from Saxony ruled the city from the late 10th century to the early 11th century, during which time Otto I, who became emperor in 955, stands out. Ottonian power extended over the entire West, going so far as to influence even the Church.

Bishop Leo of Vercelli, an ecclesiastical follower of Otto III, played a relevant role in the imperial politics of the time, and he even assumed the task of strategic referent between the pope and the emperor: some imperial diplomas, from theHistorical Archives of the Diocese and theCapitular Archives, testify how Bishop Leo was the main reference for some of Otto III’s concessions in favor of the Church of Vercelli. The famous Vercelli Book, preserved in the Museum of the Cathedral Treasury and displayed in the exhibition, dates back to the 10th century: it is a manuscript of which neither the name of its first possessor nor how and when it arrived in Vercelli is known, but it is known that it originated in England. Written within it are twenty-three prose homilies relating to important Church solemnities and six poetic compositions, all in the Anglo-Saxon language, and it is considered to be of great historical as well as literary importance because it contains much of the poetic production in Old English. Eleven of the twenty-three homilies are documented in the Vercelli Book alone, so the latter constitutes a valuable record both linguistically and culturally.

In the 12th century Vercelli became involved in the Peace of Constance, signed in 1183 through an agreement between Emperor Frederick Barbarossa at the head of the Holy Roman Empire and representatives of the Lombard League (including Vercelli) following the former’s defeat at the Battle of Legnano. A copy of that famous treaty is on display for review. Also on display are important illuminated codices and diplomas that testify to the political lines of the local Church, and many parchments from the Diocesan Library, including those from the Fondo San Donato; of the latter, two authentic specimens are exhibited that tell of a purchase and sale by the Canons of St. Eusebius and a testamentary bequest by Archdeacon Guala. The following century saw the rise of the Seignories with new powers given to important families, and it is to the 13th century that Cardinal Guala Bicchieri is linked, to whom we owe the great works of the city of Vercelli, such as the Basilica of Sant’Andrea, one of the first Gothic churches in Italy, and the Salone Dugentesco, an ancient hostel built in 1224 to accommodate pilgrims traveling along the Via Francigena. On display, three volumes of the Biscioni testify to the presence between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries of a university settlement in Vercelli: a pact made in Padua in 1228 between envoys of the Commune of Vercelli and representatives of the University of Padua sanctioned rules on the reception of students, the choice and salaries of lecturers, and popular activities to make the School known.

|

| Arbitration ruling by Tommaso de Maleto, Francesco de Paliate and Giacomo Roba, citizens of Vercelli, in the matter in dispute between Giorgio Avogadro of Collobiano and Antonio del fu Francesco Avogadro of Collobiano (Vercelli, January 7, 1384; parchment, 38 x 59 cm.) |

|

| Protocol, notary Giovanni Passardo, 1347-1361. The protocol of notary Giovanni Passardo contains a religious-scaramantic invocation against sudden death, written presumably during the severe plague epidemic that struck the city of Vercelli in 1361. |

|

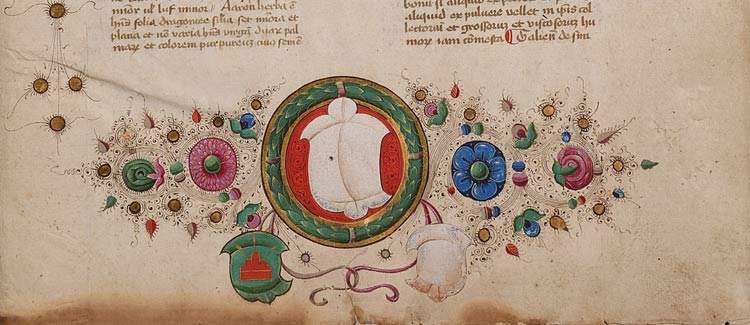

| Vercelli, Biblioteca Agnesiana, paper codex, in Latin, in bookish Gothic script, datable to the 1950s-60s. It contains the entire Liber pandectarum medicinae, also known as Medicinalis pandecta, written by Matteo Silvatico, a doctor from Salerno who lived between 1280 and 1342 and owned a garden in which he cultivated medicinal plants. |

In the 14th century the bourgeois class assumed more and more power such that the Empire and Church were forced to accommodate the growing influence of nation-states; Europe was divided between two pontiffs: Clement V transferred the papal see to Avignon in 1305, which would remain under the control of the kings of France for about seventy years, while following the Western Schism of 1378 Gregory XI once again installed the apostolic see in Rome. The power of the aristocracy and the new local bourgeoisie at the expense of the papal one is evidenced in the exhibition by the large parchment of more than two meters from the Caresana Fund of the Agnesiana Diocesan Library, in which the landed estate of a member of the small aristocracy of the Vercelli countryside is described. A family dispute that arose over the use of water from an irrigation ditch to feed a mill is then documented by an arbitration ruling of 1384: the protagonists of the affair were Giorgio Avogadro of Collobiano and Antonio del fu Francesco Avogadro of Collobiano.

In addition, interest in the new challenges of medicine was established in this period: two parchments from the State Archives that confirm this are on display. These include the Medicinalis pandecta, written around 1332 by Matteo Silvatico, a doctor from Salerno who cultivated medicinal plants in his garden, and dedicated to the King of Naples Robert of Anjou: the work was intended to provide the correct naming of simples of vegetable, mineral and animal origin. And again, a deed dated July 20, 1361 bears witness to a religious-scaramantic invocation against “sudden death” probably drafted during the plague epidemic that struck the city of Vercelli in 1361.

The review concludes with a visual experience with a strong emotional impact: the majesty of images reproducing the four medieval Crucifixes (the one from Pavia in the Basilica of San Michele, the one from Casale Monferrato in the Cathedral of Sant’Evasio, the one from Ariberto in the Cathedral Museum in Milan, and the one from Vercelli in the Cathedral of Sant’Eusebio), with special attention to the Crucifix of Vercelli.

All aspects of medieval Vercelli are recounted in a major exhibition that underscores the importance of preserving archival material in order to know and understand a complex social reality as chronologically distant from the present as that of the Middle Ages.

|

| Vercelli, an exhibition to discover the medieval city and all its secrets |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.