Uffizi, Koen Vanmechelen's fantastical creatures alongside the museum's classic masterpieces

Huge horned iguanas, a red tiger crouched in the middle of the Niobe room, never-before-seen versions of Medusa with her head teeming with fangs and pointed beaks: these are some of the fantastical creatures that populate the Uffizi for Seduction, an exhibition by Belgian artist Koen Vanmechelen (Sint-Truiden, 1965), welcomed in the Statues and Paintings Gallery and scheduled from Jan. 18 to March 20.

Thirty installations scattered among the museum’s masterpieces with a strong visual and conceptual impact will accompany visitors from the entrance, along the corridors, to the so-called “inscription shelter” room between that of Leonardo and that of Raphael and Michelangelo on the second floor, and then down to the rooms of Caravaggesque and Flemish painting that conclude the itinerary on the first.

Koen Vanmechelen, painter, sculptor, performer, and eclectic figure whose interests range from anthropology to bioethics, from the protection of human rights to bio-genetics, focuses his research on the concepts of hybridization (of animal and plant species) and contamination (of expressive techniques and materials). The artist’s practice spans a wide range of disciplines, bridging the realms of art, science and community engagement. The works in the exhibition, created especially for the Uffizi, focus on the primal, archetypal and antithetical concepts that have always fueled the human imagination: life-death, human-divine, earthly-spiritual, natural-artificial. Presented in dialogue with works from the Uffizi collection, they aim to create an evocative and disorienting journey around the idea of “seduction” and together offer a kind of hymn to the power of life and the regenerating, if sometimes monstrous, force of the natural world.

The artist began his career in the early 1990s. Central to his work is the concept of biocultural diversity, investigated through the domestic chicken and the primitive species from which it is derived. Identity, diversity, globalization and human rights are the topical themes that are interwoven in the realization of his projects. From his first wood sculptures in the 1980s, to the development of Cosmopolitan Chicken Project, a vast research program aimed at generating new breeds of poultry, to the recent creation of an immense park called Labiomista (where large-scale architecture and natural landscape installations, artworks and animals of the most diverse species coexist) Vanmechelen’s art aims at the same time to be ethical and aesthetic expression. In 2010 he received an honorary doctorate from the University of Hasselt, and in 2013 he received the prestigious Golden Nica Hybrid Art Award (Linz) and the Global Artist’s Award (Venice). To date, his work has been shown in more than 80 solo and 220 group exhibitions worldwide. He spoke as a speaker at the 2008 World Economic Forum.

Hall of the exhibition

Hall of the exhibition Hall of the exhibition

Hall of the exhibition Hall of the exhibition

Hall of the exhibition Hall of the exhibition

Hall of the exhibition Hall of the exhibition

Hall of the exhibition Hall of the exhibition

Hall of the exhibitionThe exhibition

Set up in dialogue with the works in the collection, they constitute an evocative and disorienting journey around the idea of seduction: they are a kind of hymn to the power of life and the regenerative (but also precisely hybridizing, monstrous) force of the natural world.

In the corridors of the second floor, included in the Uffizi’s tour route, among the classical statuary, the marble statuary sculptures of the Temptation series depict emperors, philosophers, warriors, heroes, and gods. Their heads are covered with fragments of eggs and other organic grafts: an invitation-challenge to break out of the limits of rational thought to follow change and indulge in unexpected contaminations. Like the one proposed by the bizarre juxtaposition of the Child with Rooster, a plaster cast by nineteenth-century Florentine artist Adriano Cecioni (ordinarily exhibited at the Gallery of Modern Art in Palazzo Pitti, “transferred” for theoccasion at the Uffizi) with Cosmopolitan Fossil, a double installation inspired by it, in which the harmless bird is transformed into an enormous iguana characterized by disturbing mutations, barely held by the child holding it.

A work played on the edge of contrasts (plastic, theatrical, psychological) is also Domestic violence: in its framework, a life-size red marble tiger lies on a carpet of chicken feathers in the center of the famous room that houses the Hellenistic sculptural group of Niobids. Surrounded by sharp blades (one of which pierces its back), a tragic reference to the desperate gestures of the ancient statues, the feline is striking in its meekness and serenity, completely jarring with the dramatic atmosphere of its surroundings. Then the image of the artist himself appears in the exhibition: he does so from the self-portrait Ubuntu, (Diasec print on acrylic, displayed right in the self-portraits room), which depicts him in the guise of a shaman, observing the visitor through a glass mask. Ubuntu, in the Bantu language, means “I exist, because we exist”-an invitation to embrace the principle of this South African philosophy and become intimately involved in the bond of exchange that unites all humanity and natural creation. The work, at the end of the exhibition, will be donated by the artist to the museum.

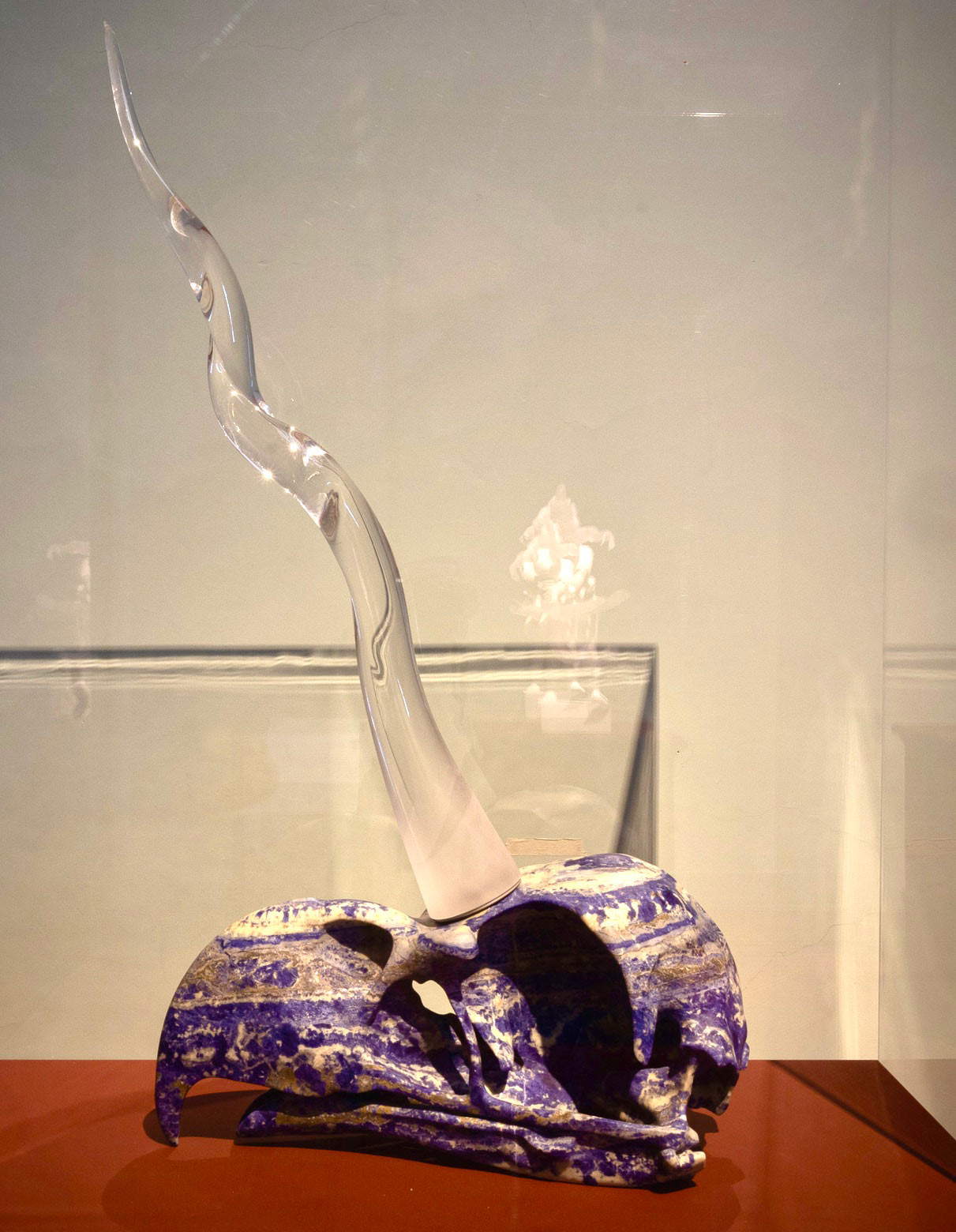

Concluding Seduction are the pair of hybrid Jellyfish in marble and glass, positioned in the main of the Caravaggesque rooms: their heads, bristling with the skulls of monstrous mutagenic chickens with their sharp jaws wide open, flank and enhance the horror of the snake hair framing the distorted face of Medusa, Caravaggio’s masterpiece. On par with the venom of Medusa and her snakes, believed in mythology to be capable of awakening from death, chicken eggs are also used in modern medicine as the basis for medicines and vaccinations. Medusa therefore is a metaphor for the ability to kill as well as to give new life.

The exhibition catalog, published by Giunti and soon available in Italian and English editions, features contributions by the curators, the artist, and Jorge Fernandez, Mario Botta, Chido Govera, and Adriano Berengo.

The exhibition is organized and produced by Gallerie degli Uffizi with Studio Vanmechelen and Fondazione Berengo.

The statements

“Vanmechelen’s works,” says Uffizi Director Eike Schmidt, “ seem to fit spontaneously among those in the historical collection, and they create hybrids between the ancient model and contemporary development analogous to the biological contamination that the artist has been personally practicing for decades in the field of nature among various species of poultry. The image of the chicken thus becomes an avatar and mirror of man, as in Diogenes’ famous commentary on Plato. In this way, artistic creation is read from an ecological perspective (and vice versa: nature becomes art) opening up to horizons of pressing relevance.”

“Right now in the Anthropocene,” says artist Koen Vanmechelen, “we need a new global renaissance. We need a cosmopolitan renaissance. This new narrative must be based on an understanding of the interconnectedness of all living things. The parallel with the Italian Renaissance is clear. Art, being designed for the future, is the means to foster and project new narratives in the world. Art has always been the connective tissue of human existence. It clarifies, opens perspectives and connects through diversity. It aspires to sow Ubuntu, a Bantu term that refers to the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity. This realization comes from seeing in the other the reflection of one’s own self-image, an image that is the bearer of the past and the future.”

|

| Uffizi, Koen Vanmechelen's fantastical creatures alongside the museum's classic masterpieces |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.