Unpublished Gino Romiti between D'Annunzio and Angelo Conti. The exhibition in Livorno and Collesalvetti

“Here is a book of faith, here is a treatise of love, composed by a candid and most fervent spirit, by an enthusiastic exegete to whom the work of art appears as nothing but religion made sensible under a living form”: these are the words with which Gabriele d’Annunzio introduced La beata riva by Angelo Conti, of whom the Vate was a friend and profound admirer. Conti’s treatise on aesthetics was published in 1900, the same year in which D’Annunzio published Il fuoco (Eleonora Duse is said to have asked him to send him both volumes: “I want to read the two books by the two brothers who are so much and so little alike”), and five years after Conti published his book on Giorgione, which provided the premises on which the critic would later base La beata riva. It was D’Annunzio who had reviewed the book on the Venetian painter, offering a reading of it that he would later also use as the introduction to La beata riva: for Conti, the art critic is a continuer of the artist’s work since he is able to penetrate the essence of his work and convey it to the public, since he is able to probe the mystery underlying his creativity, since he is able to illuminate the symbols employed by the artist. Contemplating a work of art, according to Conti, is like drawing from the water of the River Lete (hence the title of his book): it means forgetting the troubles, experiencing a moment of oblivion, “a brief respite to the anxieties of existence.” An eloquent and spiritualizing manifesto of early twentieth-century aestheticism, The Blessed Shore proclaims an almost total identification between art and life, assigns art the role of a revelation of nature (and in turn as a product of nature: “the genius work is born formed with the same spontaneity with which every living organism is born formed”), compares the artist to the child who sees everything with a sense of wonder.

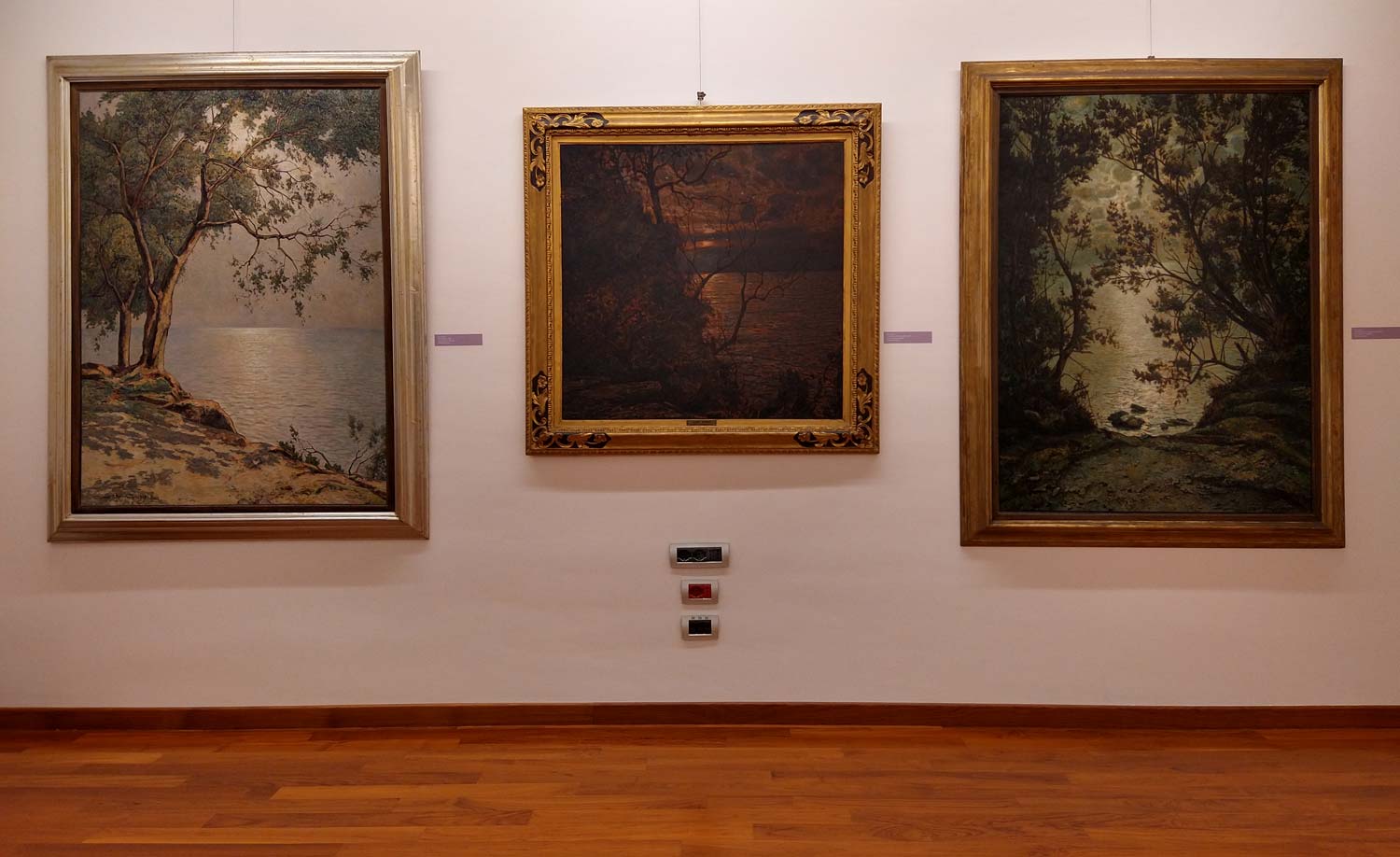

Conti’s ideas had a way of germinating in Livorno, Mo: right there, on the shores of the Tyrrhenian Sea, Conti’s aestheticism contributed to revitalize a fervent and fertile environment, where the lesson of Guglielmo Micheli had given sap to a generation of young talents (the names of Amedeo Modigliani, Gino Romiti and Llewelyn Lloyd would suffice), where the presence of the Sicilian poet Enrico Cavacchioli kindled a widespread passion for D’Annunzian impulses, where Vittore Grubicy, who had brought to the city the Divisionist verb, where younger people were fascinated by the esotericism of the Belgian Charles Doudelet. This was the climate in which the inspiration of one of the greatest artists of the time, Gino Romiti, was formed and developed, and he was not immune to the spell of D’Annunzio’s myth, Conti’s mystical sense of beauty, and Cavacchioli’s charisma. And this is the thesis at the heart of the exhibition La beata riva. Gino Romiti and Spiritualism in Livorno, curated by Francesca Cagianelli, which the Fondazione Livorno and the Pinacoteca Comunale “Carlo Servolini” in Collesalvetti are dedicating to the great and prolific painter from Livorno, focusing on a very specific period of his career: that which goes from his training until the 1930s, a period from which his production will settle on the landscape strand and will no longer be attracted by the spiritual visions of his youth.

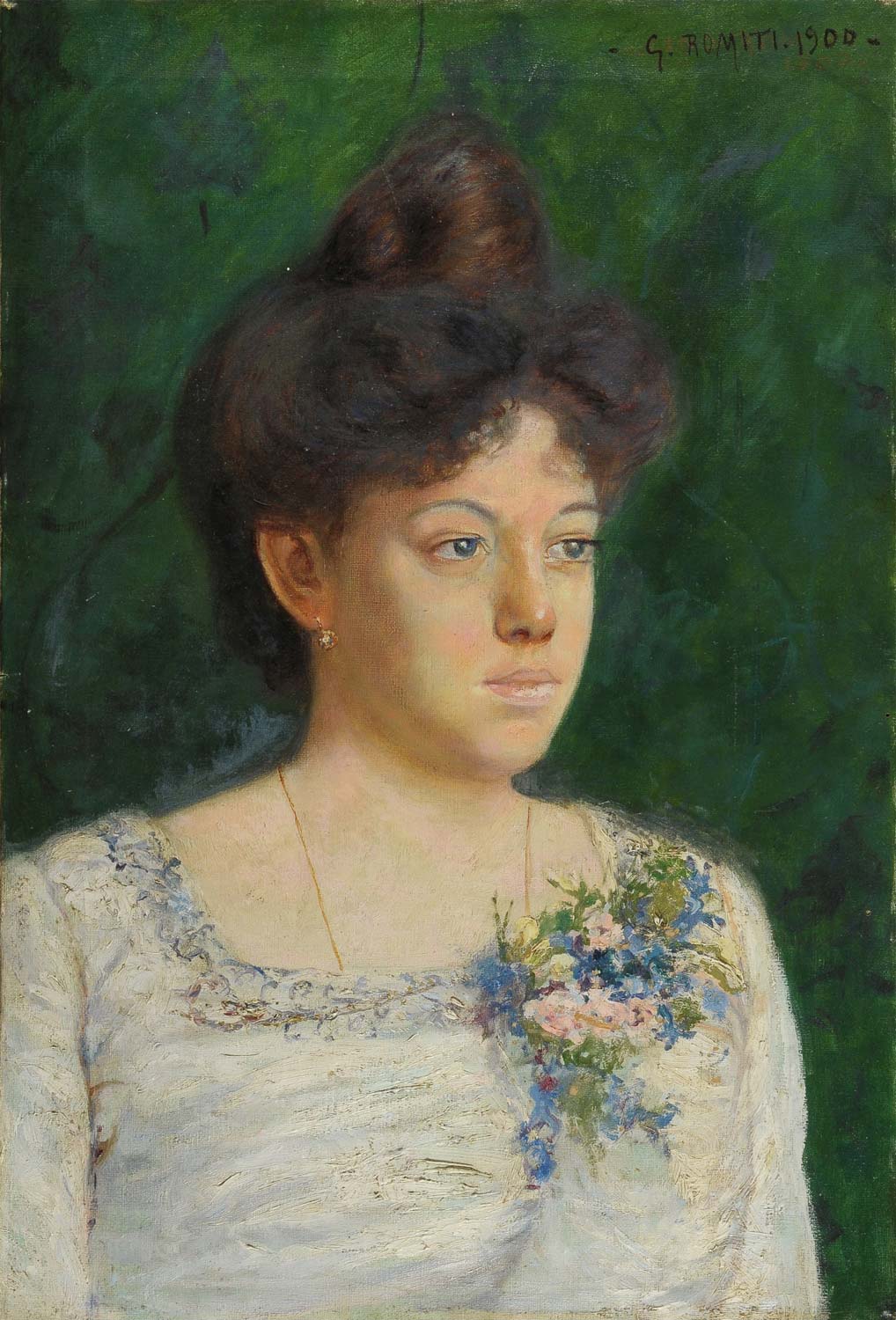

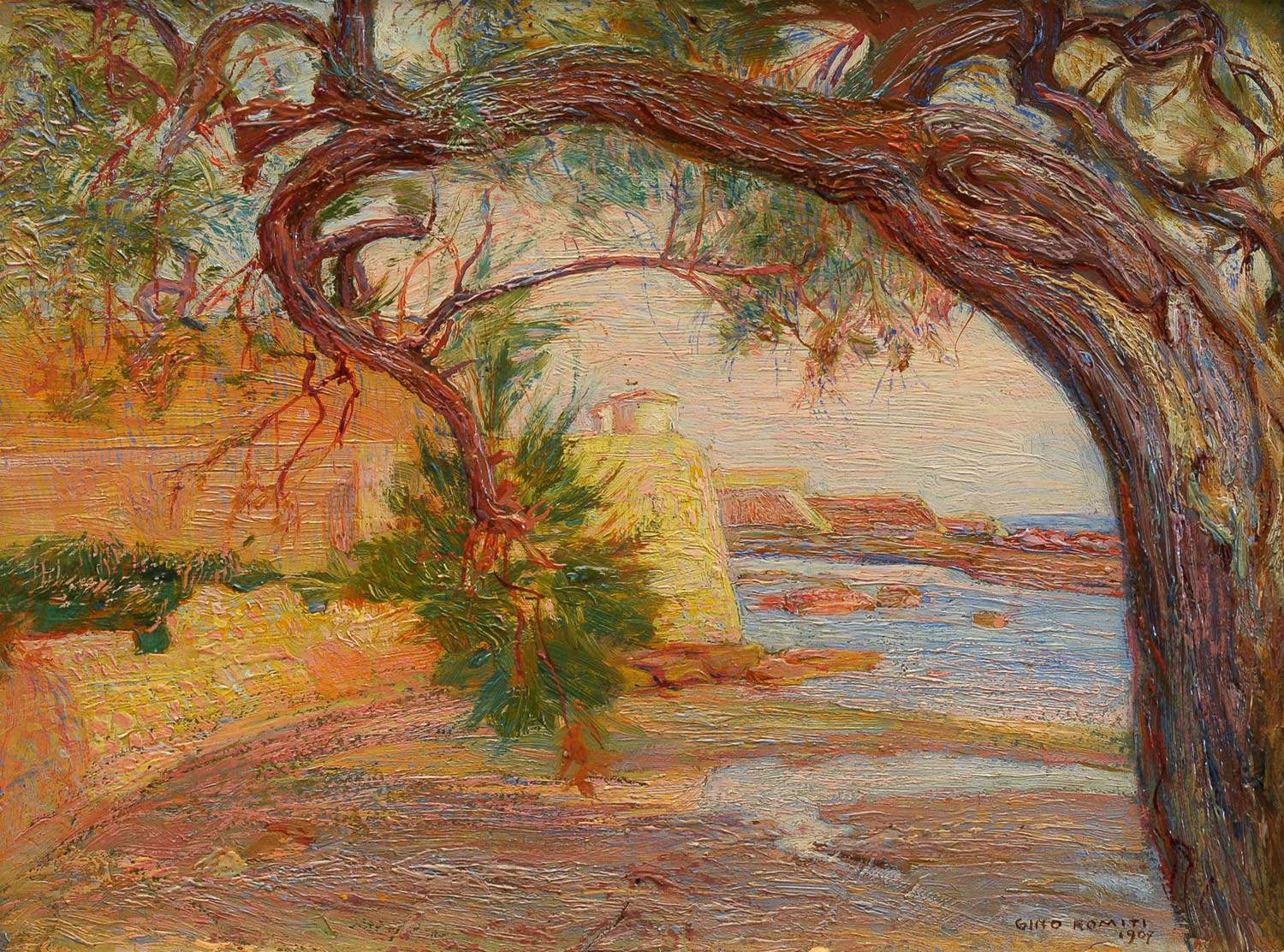

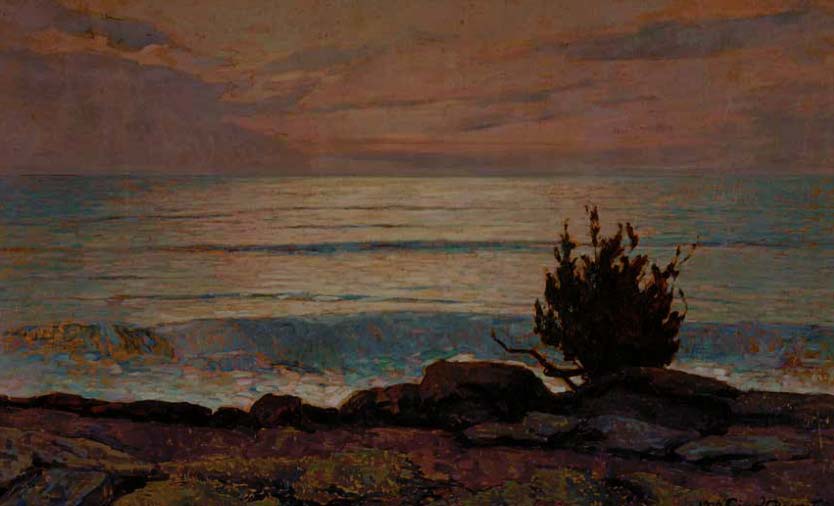

At the Livorno Foundation, however, the exhibition begins by probing Gino Romiti’s growth even beyond the fascination he had for esoteric and spiritual themes, following the Leghorn artist from his beginnings, which took place in the furrow of a far more traditional painting than that of which he would later become capable: thus, the beginning of the exhibition, with the first section on the early stages of Romiti’s career, is entrusted to a pair of portraits(Woman with Myosotis and Portrait of a Lady, respectively of 1900 and 1901) that reveal the attitude of an artist still aligned with Macchiaioli painting, although the Portrait of a Lady, in the light that strikes the face, enlivening it with unexpected flashes, and in the background that, fluidly, envelops the woman’s profile, already hints at the first signs of a change that would punctually arrive with the subsequent paintings that the exhibition aligns in strict chronological order. Arranged on a single wall are a 1907 Tamerice, a foreshortening of the Livorno seafront where one can glimpse the first approaches to the divided brushstroke, and then above all a Marina and a Sinfonia del mare of 1909 in which Romiti’s language of approaching nature with a lyrical tenor (even in the choice of the titles of the paintings) is already shown to be fully accomplished: the eternal poetry of the sea that will resonate so much in Romiti’s soul, throughout his long existence, in these paintings becomes crepuscular light that delicately refracts on a calm sea made whitish by the reflections of the light of the last sun that strikes the ripples of the blue expanse, within compositions always under the banner of the most composed balance between the measure of the sea and that of the land. From these early works, Romiti shows that he is well able to speak the “words of art,” to use an expression of Conti’s: “nature,” he wrote in the first pages of La beata riva, “even in its apparently calmer aspects (indeed maxims in these) is all a pang, it is all a frenzy to reveal itself and to express, by means of man, the secret of its life.” The good artist is the artist who can give voice to the words of nature through the words of art.

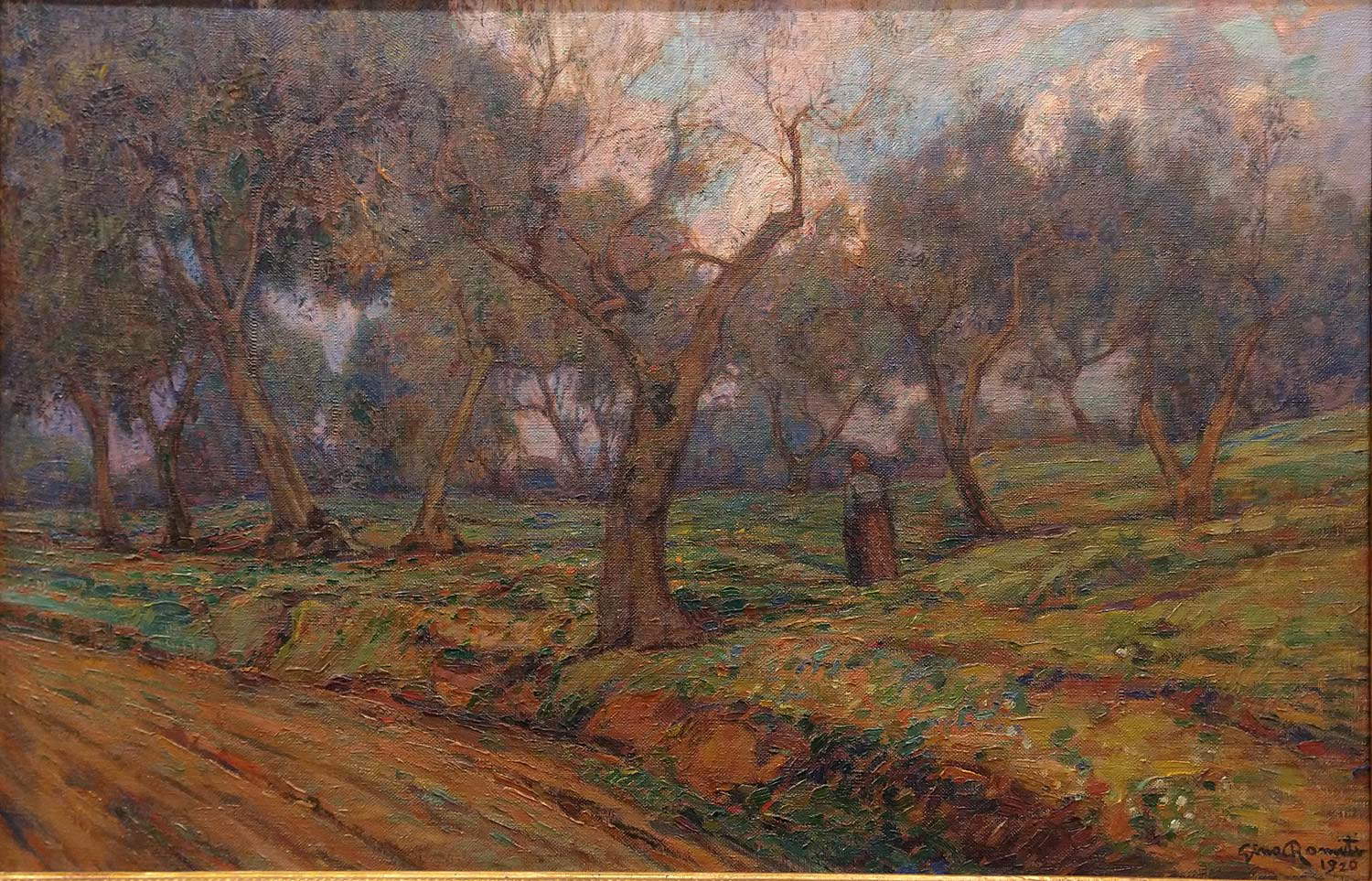

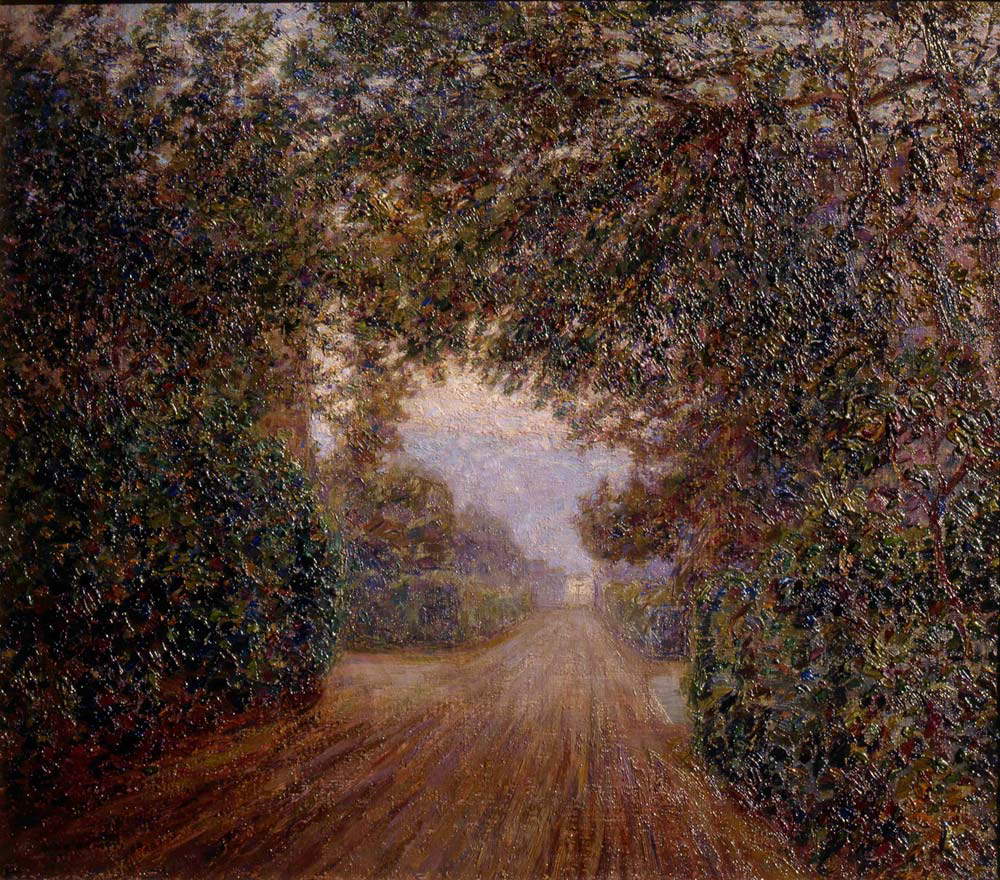

On those dates, however, there will also be no lack of digressions in the Romitian repertoire on that “funerary decadentism borrowed from Cavacchioli” and thus in Doudelet’s “Rosicrucian aesthetics,” as Cagianelli writes in his catalog essay. This will be seen, however, in the section at the Pinacoteca di Collesalvetti: the chapters at the Livorno Foundation focus, on the contrary, on the “declination of the Divisionist formula already elaborated during Michelangelo’s alumnuship in the direction of the pantheistic register” traversed by Vittore Grubicy, to whom Romiti approached already in the early twentieth century. It is to Grubicy that the paysage-état d’âme tenor of Romiti’s views, including the seascapes, refers in general, and it is Grubicy who is also recalled by certain compositional solutions, such as the constant presence of slender trees in the foreground that almost act as a filter between the relative and the landscape: we observe this in some sylvan views such as the Tempietto in the park or The Sun in the Villa, but the memory of Grubicy’s lesson will be vivid even years later, as in theUliveta of 1920 (of which a scaled-down version of the one on display in the exhibition is also known), and in some works in the second section (entitled La gioia infinita: Toward Eternal Melody), starting with Tramonto e plenilunio velato from 1924 and even Poesia della notte - Quercianella from 1938, which bring to mind the celebrated and seminal Winter Poem by the Milanese artist, who with his group now preserved at the GAM in Milan probably touches the pinnacle of the Italian mood landscape. Bridging the two sections is a marvelous Sunset, preserved in the collection of the Livorno Foundation, which is perhaps among the works that most reveal Romiti’s talent, his originality of a painter who, as Cagianelli herself pointed out in her 2007 monograph, knew how to evolve macchia painting (Romiti had been a pupil of Giovanni Fattori, as well as Micheli) into a profoundly evocative art, rich in Symbolist accents, and where a landscape piece is not never simple mímesis, but is, if anything, a poem expressed with colors; it is the artist’s feeling that invests a stretch of coastline, a forest, a cliff, a cliff on the sea, a glimpse of the countryside, and lights up in unison with what he sees. The value of a painting, Romiti himself said, is such “insofar as it succeeds in expressing a state of mind and not insofar as it is capable of offering the observer a pleasant, elegant, harmonious play of colors and lines.”

And Romiti, wrote critic Giovanni Rosadi in 1922, commenting on the very Sunset that was already in the collections of the Cassa di Risparmio di Livorno at the time, “takes pleasure in gathering the emotion he receives from the aspects of nature and portraying them in imaginative forms, sometimes bizarre, but always enlivened by a balanced sense of harmony.” The second section of the exhibition thus offers visitors a nucleus of meditations on the theme of the moon, the one that perhaps in the 1920s most and best moved the painter’s soul. Mario De Maria, the “Marius Pictor” who had already exhibited in Livorno in the 1870s and who would shortly afterwards do the illustrations for Gabriele d’Annunzio’s Isotta Guttadauro, an artist highly appreciated by Angelo Conti for the ability of his images to awaken “sleeping fantasies,” as Conti himself would write (under the pseudonym “Doctor Mysticus”) reviewing an 1887 exhibition of his in La Tribuna, in which he praised his “fantastic moon, deeply melancholy, like his soul.” And how can we not also catch a reflection of Romiti’s soul in his Plenilunio velato, a work of the Livorno Foundation in which the full moon appears almost shy, hidden behind the dry branches of a shrub, concealed by a light blanket of clouds, but still strong enough to illuminate a stretch of coastline and show us its profile? Or again in Factor’s Marina of 1929 and Lunar Nocturne, works where the moon cannot be seen, but its presence lives on in the light that illuminates a placid and serene sea, whose scent we almost seem to smell, the melody of the waves caressing the dark expanse of the rocks that contrast with the whiteness of the illuminated water? Or in the more troubled Winter Poem, where the rough sea and the profile of the coast recall elements undoubtedly Nomellini-like? We seem then to find, in the figure of Romiti, the poet “pious and enemy of sleep” who is moved before the moon in Baudelaire’s famous Tristesses de la lune: “Un poète pieux, ennemi du sommeil, / Dans le creux de sa main prend cette larme pâle, / Aux reflets irisés comme un fragment d’opale, / Et la met dans son coeur loin des yeux du soleil.”

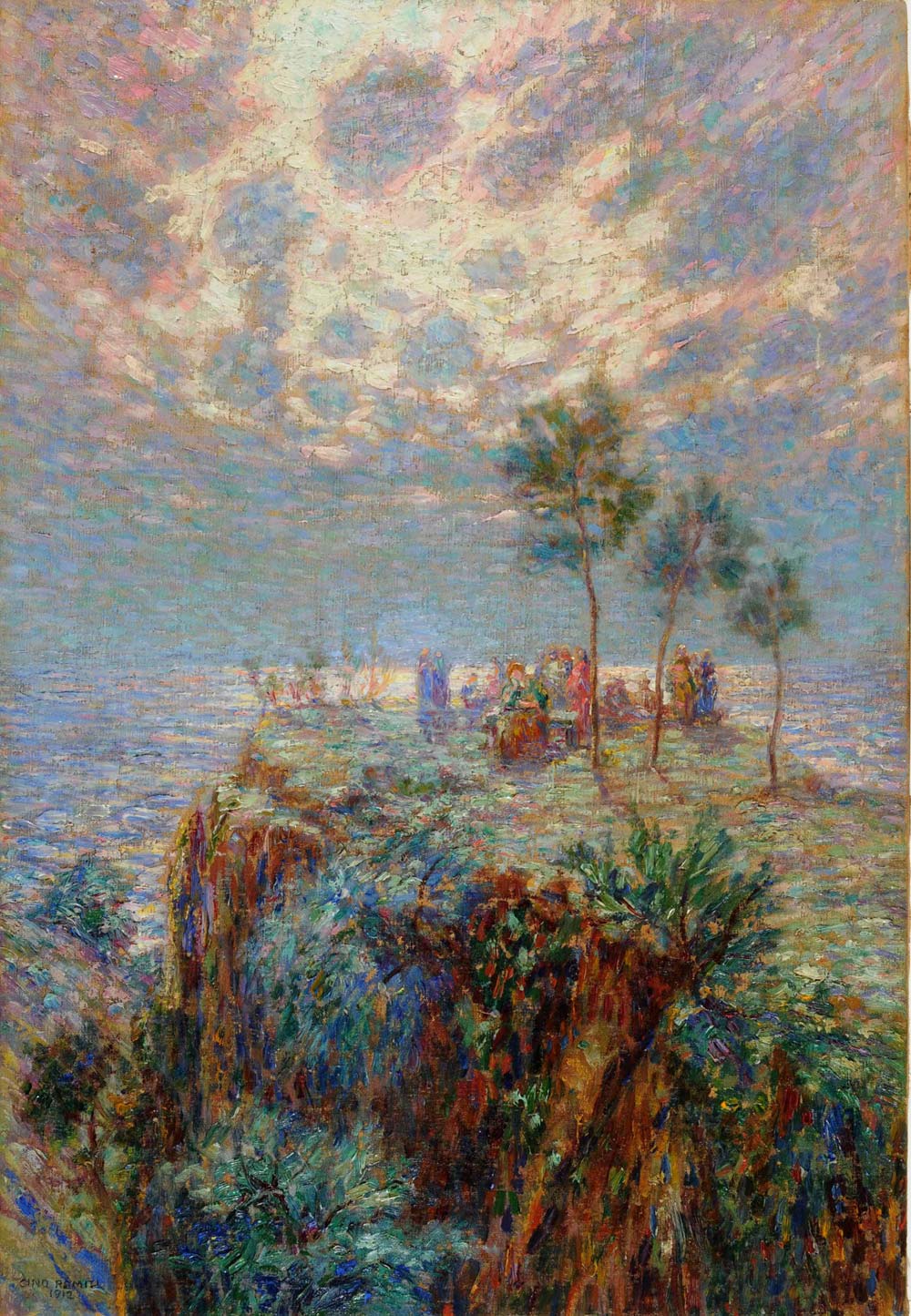

Moving on to the Pinacoteca di Collesalvetti, one will visit the most original section of the exhibition, the one aimed at capturing the path of the spiritual Romiti, beginning with an unpublished work from 1903, Centaur in the Woods, which Cagianelli identifies as a painting “at the origin of a whole faunal strand in the Labronian sphere,” which would later be traversed by artists such as Carlo Servolini and Mario Pieri Nerli. The origins of this image, a powerful and almost witch-like nocturne that in the exhibition dialogues with I primi canti della sera of 1900, an early attempt to free itself from the poetics of the stain in favor of research with more cryptic intonations, according to the curator. cryptic intonations, are, according to the curator, to be traced precisely in Romiti’s rapprochement with the aesthetic ideas of Angelo Conti and in the young Leghorn painter’s interest in Grubicy’s pictorial texts, in a general climate of enthusiasm for the spiritual that had invested Tuscany in the early twentieth century, in polemic with positivism, as was happening, moreover, somewhat throughout Europe. The fascination with esoteric themes also surfaces in a Contemplazione of 1912 where, a rare case in Romiti’s production of these years, we notice an assemblage of figures on the top of a cliff overlooking the sea, leaving us to fantasize about who they are, what they are doing, what rituals they are performing as they sit in a circle under the dim serene light that invests the Labronian coast. The subsequent large-scale work I giardini del mare of 1914, on loan from the Cirulli Foundation in Bologna, not only evokes the harmonious musicality of so much of Romiti’s painting (it will be worth pointing out that much of the artist’s output cannot be explained without imagining the inspirations that he had to take from music, always on the wave of Conti’s aesthetics), with those blades of light that mark perhaps the highest point of tangency of the Leghorn painter with the coeval research of the Futurists, allow, like the painting just before Verso la luce exhibited on the same wall, a lunge on the “gardens abandoned in the shade” on which, in the catalog, the scholar Dario Matteoni intervenes with a dedicated essay, in search of possible “D’Annunzian scenarios” that Romiti could perhaps derive from reading Gabriele d’Annunzio’s Poema paradisiaco, the garden poem. The immortal verses of the Vate, who, in his poem, attributes an almost salvific role to the garden (think, among many, of the unforgettable ones in Consolation), probably moved Romiti to his images of gardens (some, and perhaps even more congruent ones, are exhibited in the Livorno section of the exhibition), although one cannot speak of mere translations. After all, Matteoni writes, “it is not a matter of subordination, but rather of a pictorial transposition of an imagery widely popularized in the artistic and literary culture of that first decade of the twentieth century.”

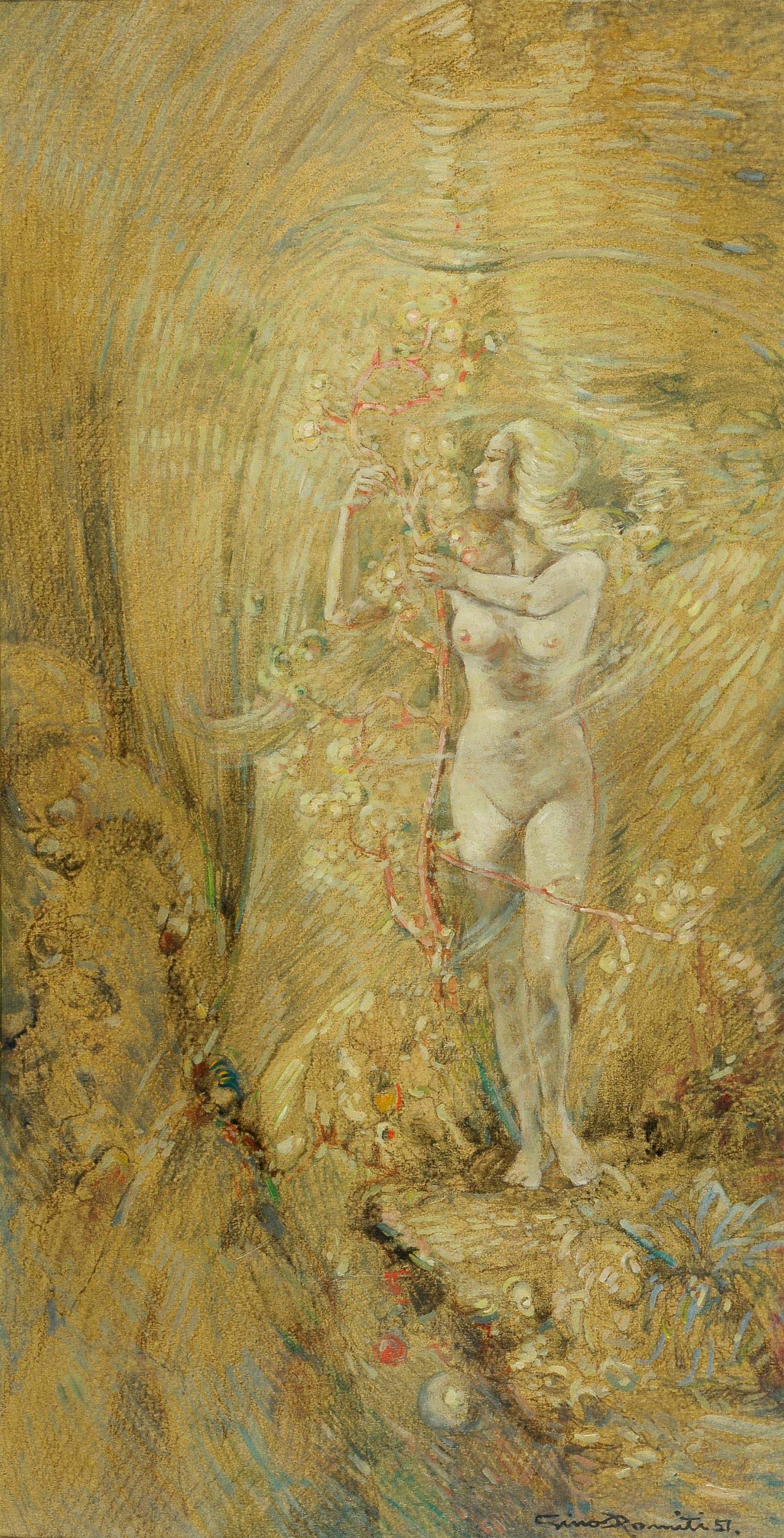

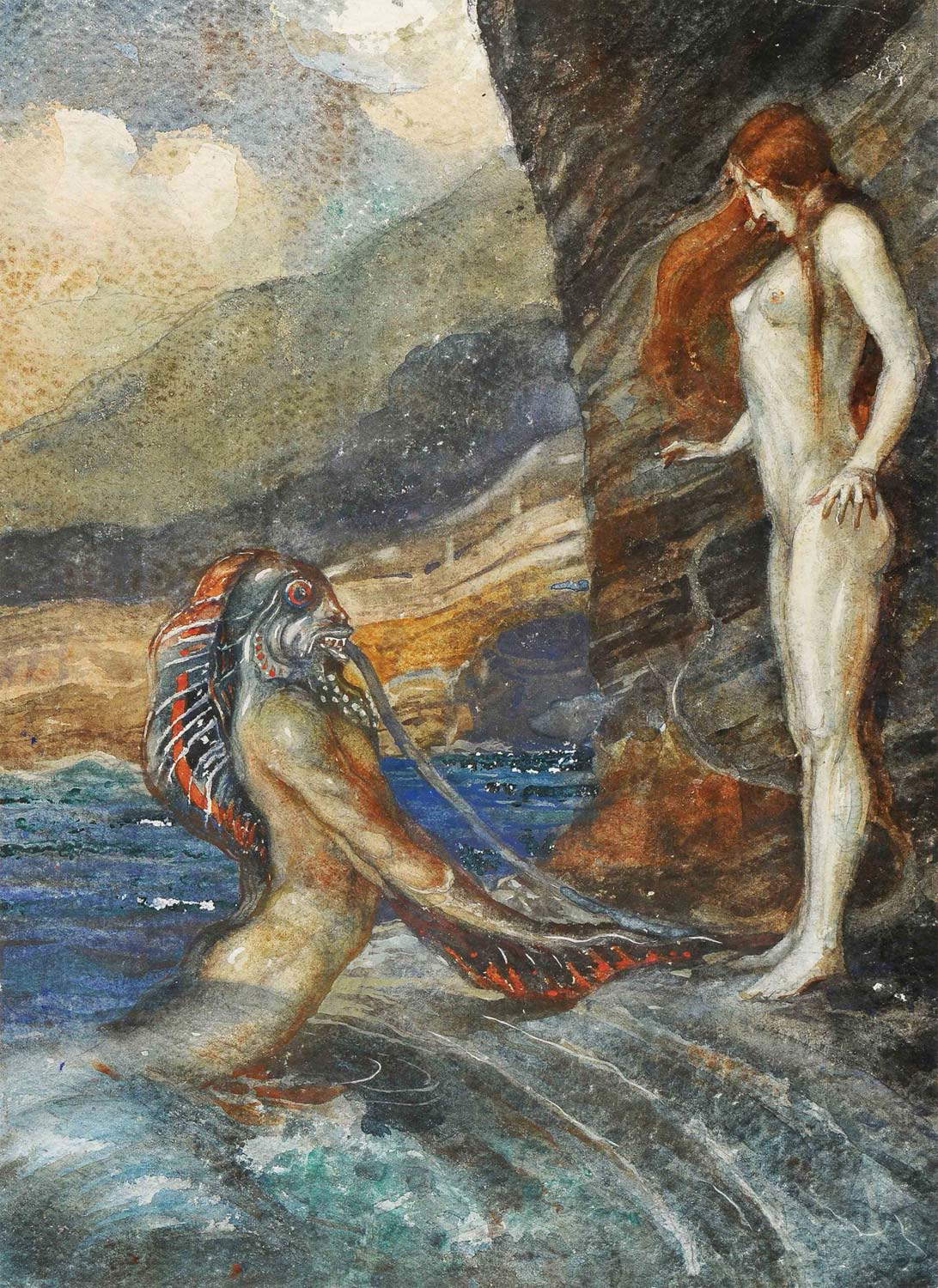

The journey through Romiti’s art concludes with a Marine Fund, belonging to a strand much practiced by the Leghorn painter (for this, in his city, he would become known as a kind of painter-palombaro, although in reality he never once dived in his entire life: he liked to reiterate that his backdrops were the fruit of his intuition, of his imagination), and with two works where the theme of the fantastic makes its full entrance, since The Ambush and the Mermaid feature graceful sea creatures moving among the waves. It is interesting to note that Mermaid is the only work in the exhibition that does not belong to the period investigated by the curator: it is in fact a 1957 panel, thus of Romiti’s extreme maturity, placed at the end of the itinerary to show how, despite his turn toward more reassuring themes, so to speak, starting in the 1940s, his interest in certain subjects pursued since the beginning of his career would never wane.

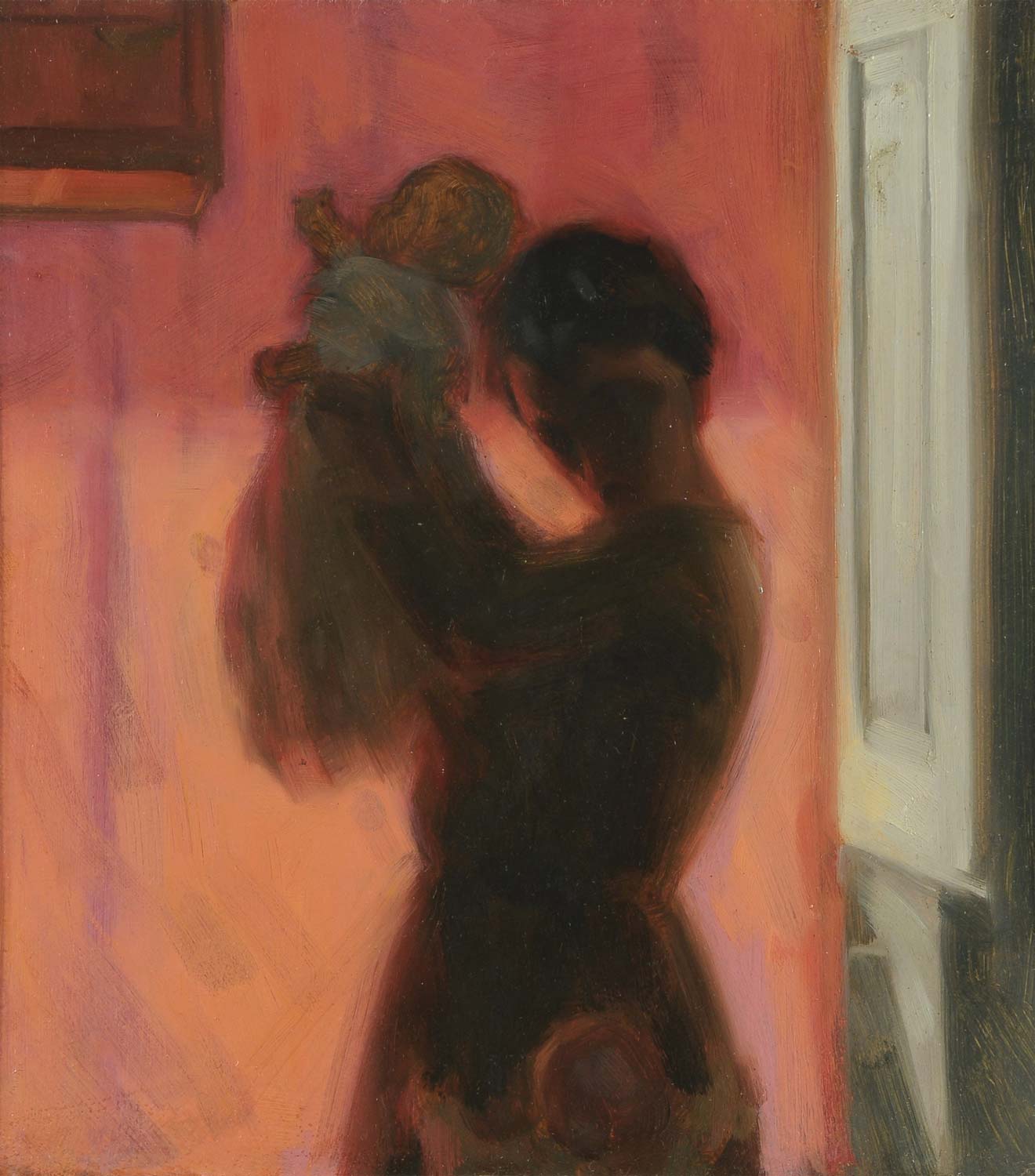

The exhibition ends with two sections that reconstruct the context in which Romiti operated. The first, The Face of Blue. Protagonists and cenacles on the Tyrrhenian shore between Micheli’s school, Caffè Bardi and Bottega d’Arte, presents a theory of works by artists who frequented the same circles as Gino Romiti: here then is Llewelyn Lloyd, who like him studied at Micheli’s, present with two works; here is anEpopea by Plinio Nomellini from 1904, one of those seascapes that Romiti will keep present a few years later for his “poems of the sea,” and then again the unfailing Charles Doudelet, an unusual and poignant Renato Natali(Lovers of 1910-1911), a very rare artist rediscovered on the occasion of this exhibition, Giuseppe Maria Del Chiappa, present with a Neo-RenaissanceAllegory, Manlio Martinelli’s poetic Maternity, and then some younger artists who would come together right around Romiti himself. Among them it is worth mentioning Mario Pieri Nerli who explores the themes of the fabulous(La fanciulla e il mostro marino), a much more earthly but no less powerful Gastone Razzaguta in describing, in his 1917 Miseria, a poor fishermen’s family against the light, sad on a dock immersed in mist, and then Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona with his oriental fantasies. Also present are some imaginative artists close to Grubicy’s pointillism, reinterpreted, however, in a more radical, almost extremist key: Benvenuto Benvenuti and Adriano Baracchini Caputi, both driven by a firm desire to probe innovative techniques. The closing is entrusted to a focus on the theme of the mermaid, with engravings collected by Emanuele Bardazzi (who also dedicates an essay to the subject in the catalog) to probe the fortune of this mythological figure in European art of the time: thus ranging from Rops to Waterhouse, from Greiner to Alberto Martini.

Gino Romiti,

Gino Romiti, Gino Romiti,

Gino Romiti,

The Livorno and Collesalvetti exhibition thus intends to open a new front of research on Romiti, who has so far been probed mainly for production more akin to that of the Macchiaioli tradition: Romiti, after all, has always been placed by critics in the groove of post-Macchiaioli painting, and the purpose of the Livorno and Collesalvetti exhibition is instead to demonstrate that his production knew a much wider variety than is usually acknowledged, thanks also to a very prolific activity at the end of his career, from the 1940s onward (an activity that is the one best known to the public and even to those who know Romiti’s art). To arrive at this new historiographical investigation of Romiti, Cagianelli probed a great deal of archival material, from which he constructed an exhibition divided into five sections that, as we have seen, portrays the beginning of Romiti’s career, setting it in the context of early twentieth-century Livorno, one of the most culturally and artistically vibrant Italian cities of the period. A Livorno that, even before the well-known experience of Caffè Bardi, which from 1908, the date of its opening, was a meeting point for the most up-to-date Leghorn artists of the time (in addition to Romiti himself, one can count Renato Natali, Mario Puccini, Benvenuto Benvenuti, Gastone Razzaguta, Umberto Fioravanti, Manlio Martinelli), already between 1895 and 1900 was “a sort of laboratory of Divisionist updates and Symbolist impulses,” writes Cagianelli: a “Livorno even mythical, transfigured by the visionary genius of some of the protagonists of a unique coterie in Italy,” in which at a very young age many of the future animators of Caffè Bardi were already participating.

A pleasant exhibition of research, therefore, which follows the one that the Collesalvetti Art Gallery dedicated to Charles Doudelet, another exhibition moved by the objective of reconstructing the cultural events of Livorno at the beginning of the 20th century, which had few equals in Italy and were of significant importance in the broader perspective of European culture of the time, despite the fact that these stories are little known. The exhibition The Blessed Shore. Gino Romiti and Spiritualism in Livorno, also thanks to an in-depth catalog, thus offers its own contribution to bring to the surface a non-secondary part of these events, as well as to make one of the most interesting artists of the early twentieth century in Italy better known.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.