If the protagonist of the major Roman exhibition dedicated to Gustav Klimt (Baumgarten, 1862 - Vienna, 1918), which was held until March 27, 2022 at the Museo di Roma in Palazzo Braschi, was undoubtedly Judith I from the Belvedere Museum in Vienna, among Klimt’s most erotically charged masterpieces, the star of the exhibition dedicated to the same artist but held at the Ricci Oddi Gallery in Piacenza and theXNL - Piacenza Contemporanea is certainly the Portrait of a Lady. The Piacenza exhibition, curated by Gabriella Belli and Elena Pontiggia, in fact intends to celebrate the painting’s definitive return home, with which the Roman exhibition ended. Instead, the exhibition itinerary designed by the gallery around this work places it inside a kind of isolated niche against a completely dark background to give it even more prominence, about halfway up the second exhibition floor, where the visitor comes face to face with Klimt’s mature masterpiece in a collected atmosphere. A video preceding it recounts the troubled affair related to the painting that shocked the art world and beyond for several years. A story of a theft and an unusual find that took place after more than 20 years and that today results in great joy at the work’s return to its original home.

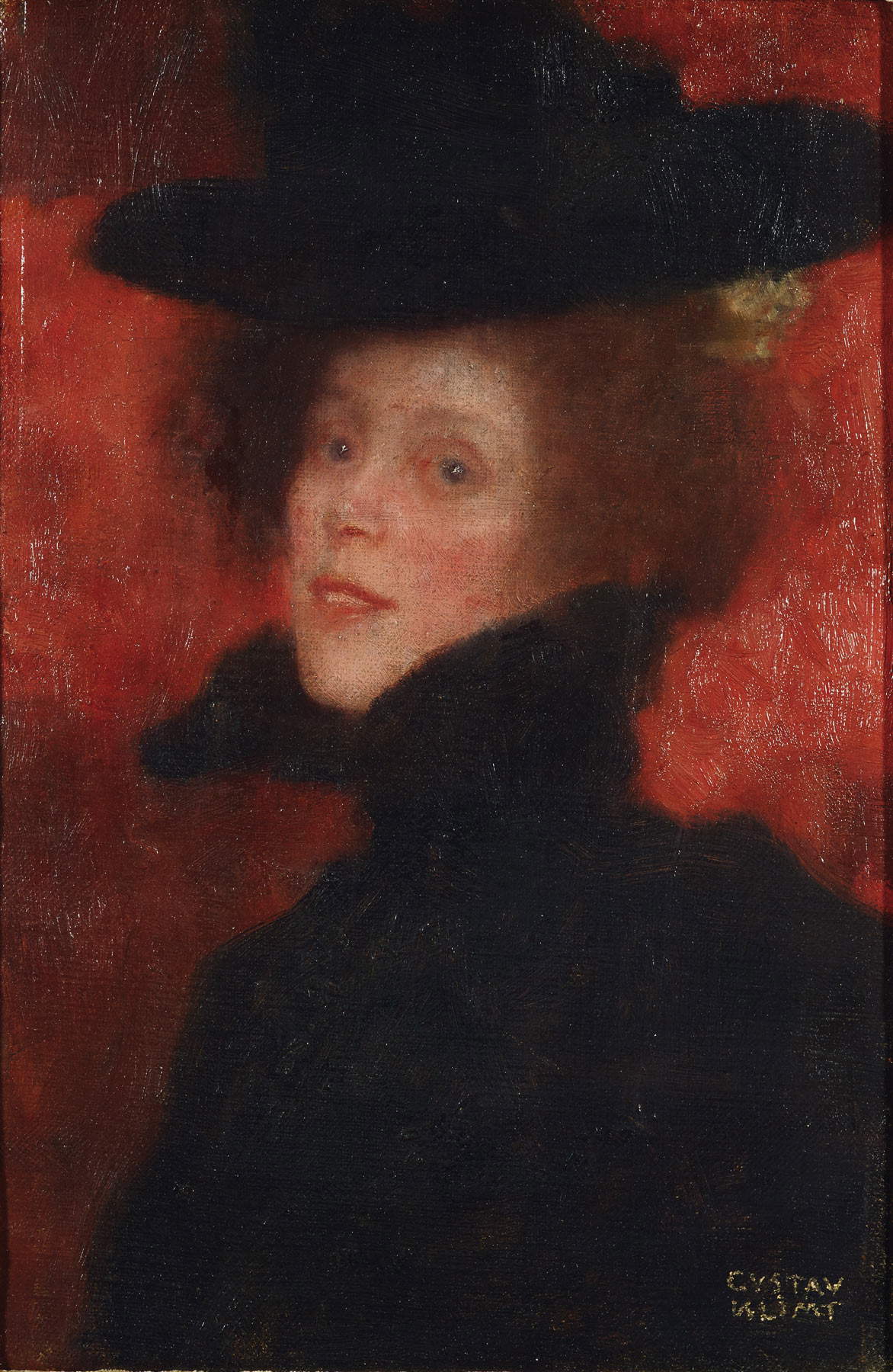

In fact, it is recent news history that the Portrait of a Lady was found in a black sack inside a small compartment closed by a door without a lock in the courtyard of the museum, which was followed by investigations to verify its authenticity: it was December 10, 2019, gardening work was underway along the outside wall of the museum, and twenty-two years had passed since that incredible theft that occurred in February 1997, when during the stages of packing the works for the preparation of the exhibition Da Hayez a Klimt. Masters of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries at the Ricci Oddi Gallery, curated by then-director Stefano Fugazza and staged at the Palazzo Gotico in Piacenza, Klimt’s painting disappeared, we still do not know how. But the story related to the painting, traced very clearly in the two catalog essays written by Franz Smola and Lucia Pini, has even more incredible when one considers that it was a high school student from Piacenza, Claudia Maga, who discovered in 1996 that there was another portrait underneath the Portrait of a Lady, which was believed to be lost and that instead Klimt painted the Ricci Oddi version on it (a hypothesis confirmed by the investigations that began thanks to the confrontation with Ferdinando Arisi and Stefano Fugazza, president and director of Ricci Oddi, respectively): Referred to as Backfisch, or “young girl” in the current Austrian parlance of the 1910s, the lost portrait depicted a young woman identical in face and pose to the present one, but dressed and styled differently, characterized above all by a large black hat. This was an element that became frequent in Klimt’s portraits at two particular moments in his career, namely at the end of the 19th century, as seen in the Lady with Cloak and Hat on a Red Background, featured in the exhibition and from the Klimt Foundation, and between 1907 and 1910, when the fashion for large hats was accompanied by the presence of a showy feather boa or large stole. The only reproduction of Backfisch can be seen in an essay by Franz Servaes on the artist published in Velhagen & Klasings Monatshefte magazine that probably dates from 1918: Klimt repainted presumably Backfisch between late 1916 and 1917, making the hat disappear and freeing the neck from the scarf, and finally changed the title to Portrait of a Lady. As far as the pose is concerned, it turns out to be very similar to the painting Portrait of a Lady in White, also in the exhibition: the body slightly leaning forward, the face looking at the viewer with a smile on her lips, and the flowered fabric falling over her shoulders.

Given the temporal proximity between the Roman and Piacenza exhibitions and the similarity of the themes addressed through the most salient moments of the artist’s career, from the Viennese Secession to his mature production, and the Italian heirs to his art, Klimt. The Man, the Artist, His World, that’s the title of the exhibition at the Ricci Oddi Gallery, could have been a short-form copy of the Museum of Rome show, but instead it gives the public some surprises. Many of the works exhibited at Palazzo Braschi can be found here as well, remixed and juxtaposed in different ways; the size of the exhibition is much reduced, and the presence of Judith I was not been bisected (the great masterpieces are all presented together at the end of the exhibition in a portfolio), but the additions include, for example, several etchings by Max Klinger from the series The Glove, lithographs by Edvard Munch, an entire section devoted to publicity posters for Vienna Secession exhibitions, drawings by Oskar Kokoschka along with drawings by Egon Schiele, the latter already present but to a lesser extent, and all four panels of Vittorio Zecchin’s The Thousand and One Nights .

However, the room with The Beethoven Frieze inspired by Wagner’s interpretation of the Ninth Symphony, which Klimt had presented at the 14th Secession Exhibition in 1902 and which can be seen today in Vienna’s Secession Palace (the one on display is the full copy of the work made in 2019), is found, as well as various objects from the Wiener Werkstätte, whose production led by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser intended to bring design into everyday life. Postcards testifying to Klimt’s travels to Italy are also missing, and his relationship with the Bel Paese is hardly addressed (in the Rome exhibition, three sections analyzed his participation in the Venice Biennale of 1899 and 1910, the Rome International Exhibition of 1911, and the II Roman Secession of 1914), except for his legacy in some Italian artists, such as Vittorio Zecchin, Felice Casorati, Galileo Chini, Adolfo Wildt, and Luigi Bonazza.

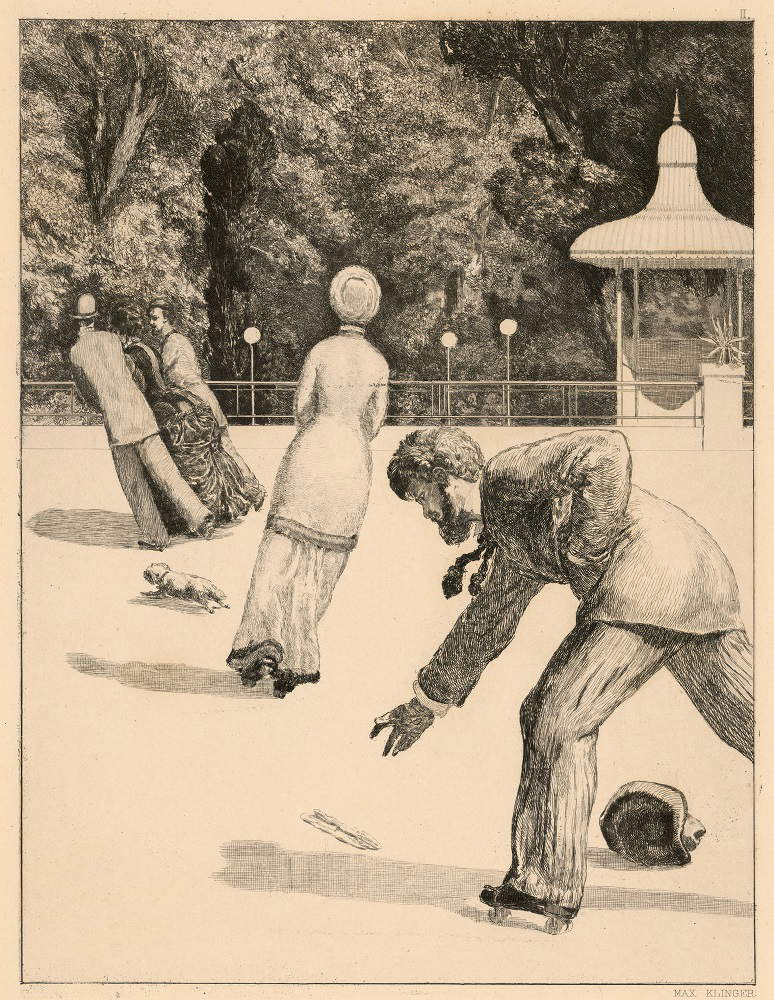

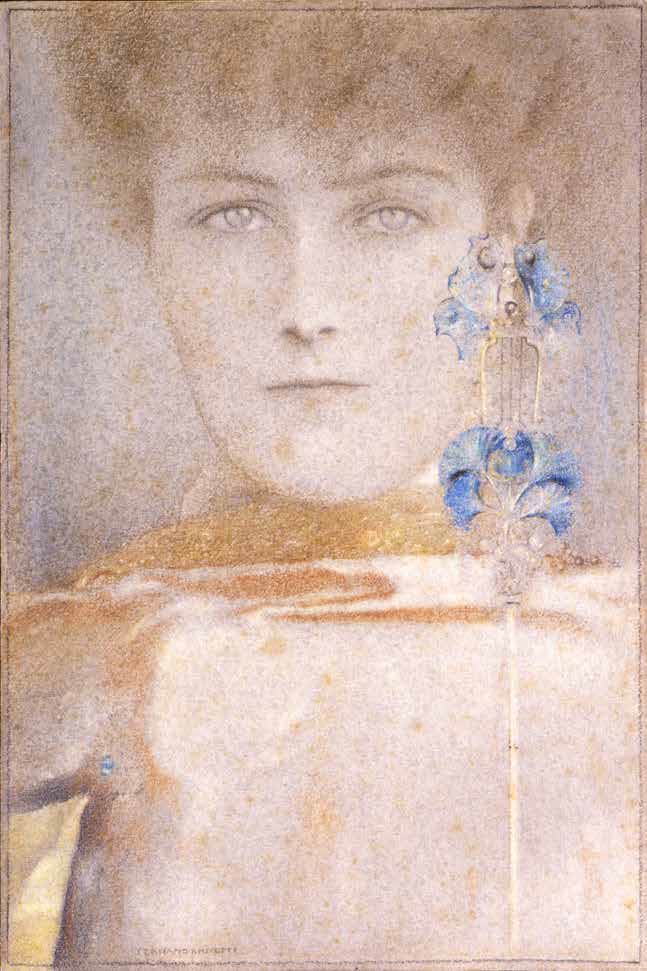

The exhibition opens with works from European Symbolism, the context in which Klimt was formed and which dominated the European art scene after and in opposition to Impressionism. These are works populated with demonic elements, mythological characters, dark forces, and harking back to the dreamlike sphere, vision, and fantasy. Thus we see as anticipated the series of The Glove by the German Max Klinger (Leipzig, 1857 - Grossjena, 1920), in which the artist imagines a story that begins with a young woman who loses her glove while skating until the kidnapping of the same glove by a monster who quickly emerges from a window; engravings by Norwegian Edvard Munch depicting a world populated by ghosts, a mysterious female figure by Belgian Fernand Khnopff, and an interpretation of the ancient myth of Medusa by German Franz von Stuck are then exhibited.

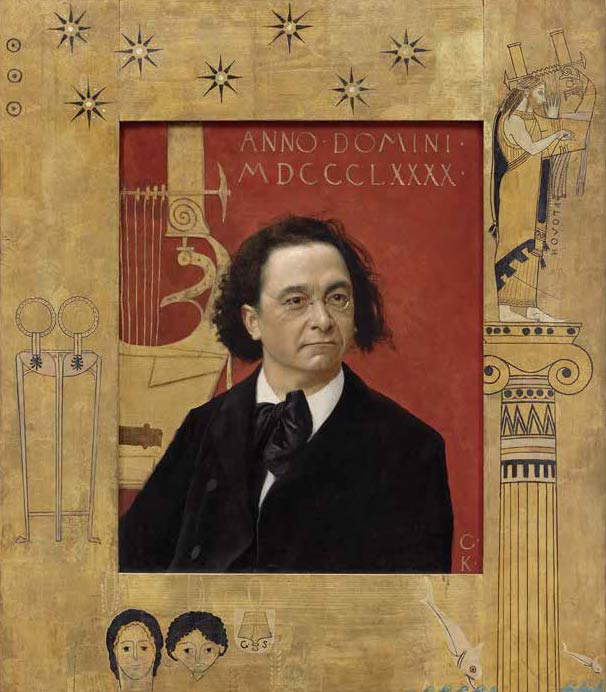

After this introductory section, Klimt’s beginnings are then presented with pencil sketches of still academic male nudes and sketches for theatrical settings, such as the Karlsbad Municipal Theater Curtain Sketch. In fact, together with his brother Ernst and his friend Franz Matsch (Vienna, 1861 - 1942), the artist founded the Company of Artists in 1879: Matsch’s sketch for the ceilings of the staircase of the Burgtheater in Vienna is on display. With the third section, the exhibition presents Klimt within the Viennese Secession , which the artist founded in April 1897 with a group of artists who had broken away like him from the Wiener Künstlerhaus, the official association of Viennese artists. The Vienna Secession had twenty-three members, of which Klimt was president for the first year, and was intended to be an art that corresponded to the needs of the time in Austria. Along with Joseph Pembauer’s Portrait of Joseph Pembauer, Portrait of a Woman, Lady with Cloak and Hat on a Red Background, and Lady in Front of the Fireplace by Klimt, works by other members of the Secession, such as Carl Moll and Koloman Moser, are exhibited.

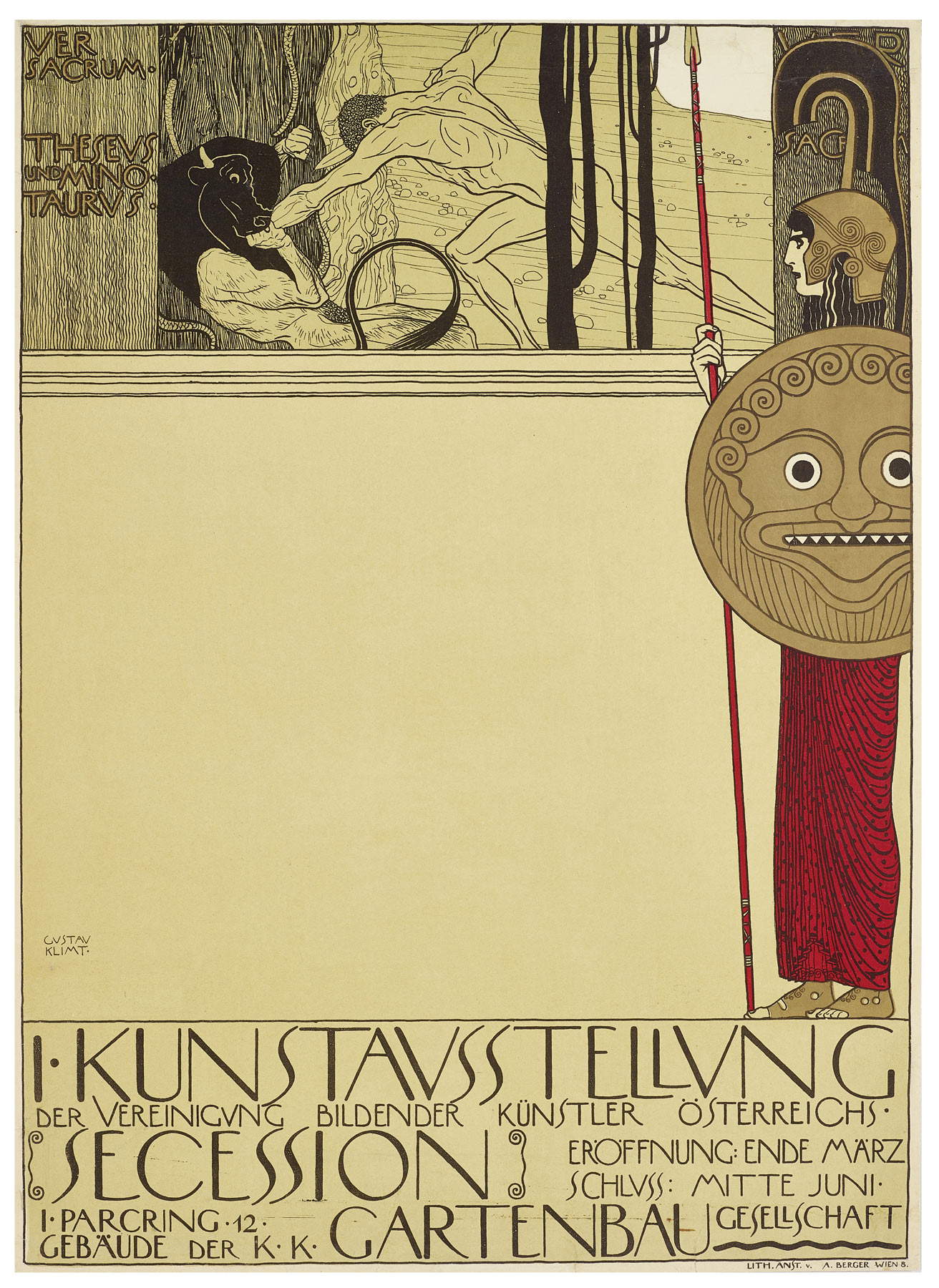

Here begins an interesting section devoted entirely to publicity posters for Vienna Secession exhibitions, including Klimt’s two versions of the poster for the first Secession Exhibition, illustrating Theseus struggling with the Minotaur: the first version with the Greek hero completely naked, which was, however, deemed scandalous and immoral because it showed nudity, and the second version censored by a gimmick; in the poster for the second Secession Exhibition in 1898, Joseph Maria Olbrich illustrates instead the Secession Building he had designed with the famous dome of golden laurel leaves. This is followed by Secessionist journals, first and foremost Ver Sacrum whose name “Sacred Spring” refers to a mythological tradition of ancient Rome that those born in spring were sent to found new settlements once they became adults, and decorative objects and furniture components belonging to the Wiener Werkstätte, founded in 1903 by Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser with the indutrial Fritz Wärndorfer on the model of the BritishArts and Crafts movement.

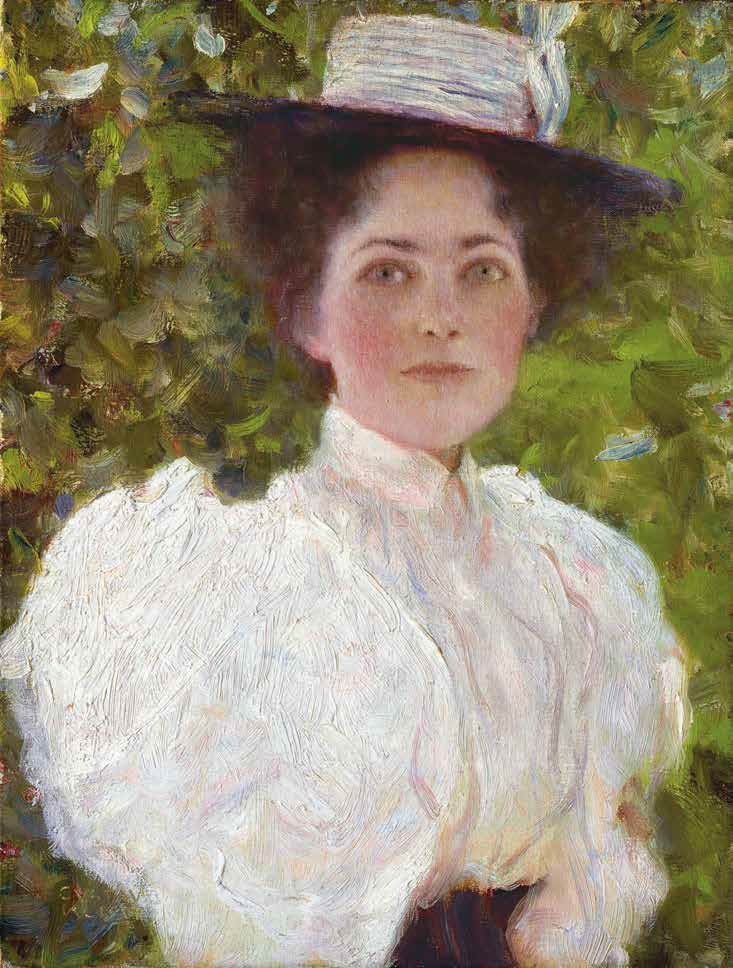

After the section with Egon Schiele’s erotic drawings , which are placed with a more dramatic, neurotic and more driven stroke along the lines of the works full of eroticism and sensuality by Klimt, and lithographs imbued with reminiscences of folk art by Oskar Kokoschka.Closing the second floor of the exhibition is a section devoted to a series of Klimt’s portraits , such as the young woman in a wide white blouse and hat depicted in Girl in the Green from 1898, the slightly later Old Man on his Deathbed (1900), some studies of women’s portraits, but standing out are The Friends I from the Klimt Foundation(1907), Portrait of Amalia Zuckerkandl (1913-1917) and Portrait of a Lady in White from the Belvedere Museum (1917-1918), three Klimt masterpieces.

On the second floor, a space has been set aside for the reconstruction of Beethoven’s Frieze , which runs along three walls, addressing themes that can be summarized as man’s desire for happiness, happiness thwarted by hostile forces, and the desire for happiness that is appeased in the Arts. It isArt in fact, as the catalog of the 14th Secession Exhibition of 1902 dedicated to Beethoven explains, that “guides us into the realm of the Ideal, the only one where it is given us to know pure joy, pure love, pure happiness.” Missing from the Piacenza exhibition, however, is a sketch of a sculpture by Max Klinger that portrayed the composer, displayed instead in the center of the reconstructed room at the Museum of Rome exhibition, a reminder of the original marble statue completed by Klinger that was placed at the 1902 Exhibition in the very center of the Frieze room.

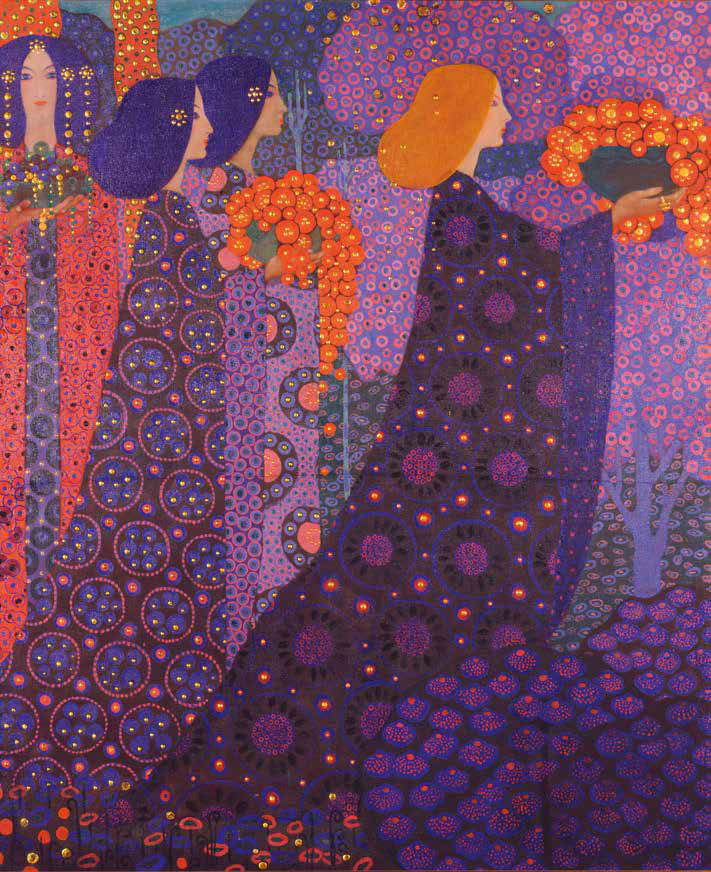

Visitors then enter the niche dedicated to the Portrait of a Lady discussed earlier and finally have the opportunity to confront the outcomes ofKlimt’s legacy, represented by some Italian followers who, influenced by Klimt’s works they saw at the 1910 Venice Biennale and the 1911 International Art Exhibition in Rome, rethought their art from a more modern and international perspective. Giving a taste of this, welcoming the public at the entrance to the second floor of the exhibition, are the four canvases from Vittorio Zecchin’s Le Mille e una notte cycle, reminiscent of Klimt’s typical mosaic composition; also part of the latter section are some vases by Galileo Chini decorated as refined handcrafted design objects and some works by Felice Casorati , who inserted Klimtian elements into a more formal and primitive art.

Unlike the Palazzo Braschi exhibition that reconstructed in one room, for the first time, thanks toartificial intelligence and machine learning, the original colors of the so-called Quadri delle Facoltà, the allegories for the University’s ballroom that the Ministry of Education in Vienna commissioned in 1894 from Klimt and Franz Matsch, the Piacenza exhibition offers in theformer Carmine Church the digital reconstruction of Medicine, one of the three paintings along with Philosophy and Law that Klimt made for the ceiling of the Great Hall. The Paintings, and particularly Medicine, were rejected by the University because they were too scandalous, sensual and too pessimistic toward science. In her essay devoted to the Paintings for the University, Elena Pontiggia reports some of the criticism after Medicine was first exhibited still unfinished in 1901 at the 10th Secession Exhibition. In the Viennese newspaper Deutsches Volkblatt, the painter Karl Schreder wrote, "It seemed impossible to overcome Philosophy, and yet it happened. Klimt has succeeded in surpassing himself. His latest creation [...] is the most vulgar thing in art that has been seen in Vienna. For those who have studied and admired the sublime creations of art, the thousands of works by the most famous masters of all times and countries, this grotesque stuff, appearing under the sacred name of ’art,’ is a real mockery." Tired of the criticism, Klimt gave up the commission by returning the fee. The works were then returned to the artist, who sold them to various buyers: the Philosophy and Jurisprudence were sold to collector August Lederer, but were seized in 1938 by the Nazis, while the Medicine was purchased by the Belvedere Museum in 1919. Then in 1944 all three were taken to Immendorf Castle, where due to fire the following year they ended up destroyed.

The Piacenza exhibition has, for those who had already visited the much-anticipated Roman show, many similarities with the latter, but the writer did not, however, catch it as a repetition or a copy of something already seen. On the contrary, it is an opportunity to admire works, particularly graphics, of the highest value. For those who, on the other hand, had not visited the Roman exhibition, the Piacenza show is a coherent and well laid out exhibition that offers the chance to see works by Klimt and his context from important Italian and international institutions, through which one can fully understand the environment in which one of the greatest artists of the Viennese Secession moved.

Once you leave the exhibition, the collection of the Ricci Oddi Gallery is then worth a careful visit, at the end of which you can ask to be accompanied to the place where Klimt’s Portrait of a Lady was found, in front of that small room where it remained for more than 20 years without anyone knowing it.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.