Surprise: the one on Van Gogh in Rome is not the usual box office exhibition

It is difficult to avoid the risk of setting up an exhibition that has already been seen when dealing with Vincent van Gogh. That is, one of the artists whose name recurs most often in the exhibition palimpsests of half the world: it will suffice to recall that, to date, as many as seven exhibitions are scheduled worldwide in 2023 that are dedicated to him in various ways(Van Gogh, Cezanne, Le Fauconnier & the Bergen School at the Stedelijk Museum in Alkmaar, Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, which will move later to the Musée d’Orsay, and then again Van Gogh and the Avant-Garde at the Art Institute of Chicago with a subsequent stop at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, Van Gogh’s Cypresses at the Metropolitan in New York, and Van Gogh in Drenthe at the Drents Museum in Assen). And the task becomes even more challenging if the curators have to deal with material identical to that of a recent exhibition: a nucleus of works on loan from the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterlo, Holland. So there was every reason for the Van Gogh exhibition, organized in the rooms of the Palazzo Bonaparte in Rome, to result in yet another commercial product exploiting the name of the great Dutch painter, with the usual Kröller-Müller selection. Indeed: with a decidedly reduced selection compared to the one that had held up the forgettable 2017 exhibition Van Gogh between Grain and Sky, curated by Marco Goldin at the Basilica Palladiana in Vicenza. In the Veneto there were as many as 129 works from the Kröller-Müller, while in the capital came exactly a third of them: forty in all, plus six paintings completely unrelated to the exhibition itinerary and useful only to present the collection of the lending museum.

The news about the exhibition thus suggested keeping expectations well below par. And yet, in the end, the exhibition at Palazzo Bonaparte turned out to be a pleasant surprise: an exhibition that does not add any particular novelty to our understanding of Van Gogh’s genius, but which has the merit of being based on an itinerary that tries to give the visitor as much as possible, and intends to present Van Gogh’s short story not only from a human point of view (as is obvious and natural), but also, and perhaps above all, from an artistic and cultural point of view. The two curators, Maria Teresa Benedetti and Francesca Villanti, deserve credit for having made the best use of the paintings and drawings loaned by the Otterlo museum to order an exhibition that follows the entire parabola of Vincent van Gogh with comprehensive apparatus, capable of providing visitors with details about the artist that are usually largely overlooked by exhibitions devoted to him.

Of course, the Roman exhibition does not leave out the human vicissitudes of the painter, which cannot be separated from the product of his brush. This is what Benedetti confirms from the very first lines of his essay in the catalog (a quick but dense reconnaissance of Van Gogh’s story): “The life of Vincent van Gogh, a fragile soul, constantly in search of affection, friendship, approval and love, is marked since his youthful years by disappointments, rejections, abandonments. [...] Pain, Van Gogh’s life companion [...], is transformed, and from individual torment it becomes a universal symbol of suffering proper to the human condition. [...] Ignored in life by critics, he failed to enter the market, and yet his creative story, which lasted only ten years (1880-1890), has imprinted itself with characters of an unprecedented intensity that have generated interesting reflections carried out by exegetes among the most astute and also by personalities linked to the artist by character and psychic affinities.” The exhibition, however, does not limit itself to a mere and superficial account of the painter’s torments, but seeks to go deeper. It goes into the merits of the artist’s expressive choices, the reasons even formal ones that supported them, and the context in which they were formed. His artistic debts are explicated with abundance, although it is not possible to observe comparative works. A much more accurate and truthful image of the artist is thus restored than the image of the impulsive madman Van Gogh that has become fixed in the collective imagination. Each work is accompanied by a caption that, wherever possible, reports content related to it written by the artist himself in his letters. An account is given of the readings in which Van Gogh immersed himself, and the result is (finally) the image of a man who was not only the eccentric outcast bent on his own anxieties, but was also a fine reader and an educated observer, attentive to the reality that surrounded him. These are aspects known to those who know Van Gogh’s art well, but which struggle to impose themselves on the clichés of the cinematic Van Gogh, or the Van Gogh of bad box office exhibitions. So one can only welcome the project of Benedetti and Villanti (both of whom are, after all, specialists in the late 19th-early 20th century), a project that approaches Van Gogh with great respect and can be said to leave something to the visitor, who can therefore go to the Palazzo Bonaparte not only because he or she is offered the chance to see otherwise distant works (this is often the only justification for a visit to an exhibition on Van Gogh), but because he or she is given the power to gain a rather comprehensive insight into his art.

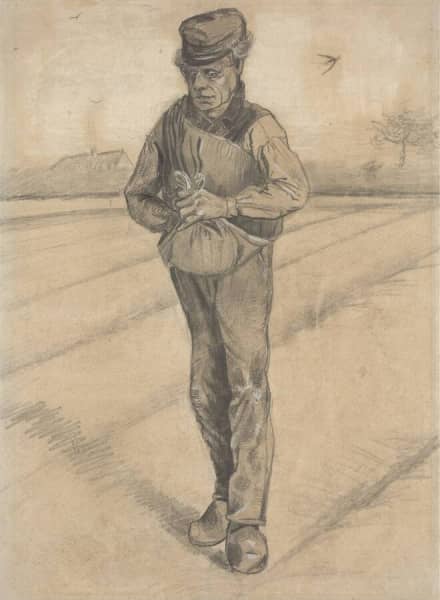

Having passed the room with the six paintings that have nothing to do with the exhibition, but which aim to introduce the Italian public to the collections and history of the Kröller-Müller (they are works by Lucas Cranach the Elder, Renoir, Fantin-Latour, Gauguin, Picasso and Verster) we finally enter the heart of the exhibition, which follows a strict chronological iteration, accompanying Van Gogh through the various stages of his career. It begins with the Dutch period and in particular with the Etten years, where his artistic story begins: the first Van Gogh is a realist artist, interested in social themes, eager to narrate with his paintings the peasant life of the poorest areas of Holland. It is a Van Gogh engaged in feverish graphic activity: in fact, it is the drawings that give an account of his early experiments and artistic orientations. The exhibition thus opens with a Sower that looks directly at the example of Millet, whose works were able to touch the Dutch artist’s religious sentiment, so much so that, writes Villanti, Van Gogh grasps in the Sower “reference to the parable of Christ scattering his words as if they were seeds among the people, a reminder of his long-standing desire to become a ’sower of the word’ when he still thought he would become a preacher following in his father’s footsteps.” The same drawing that opens the exhibition is charged with allegorical meanings, while remaining the work of an artist who was still learning his trade: the same is true of Woman Peeling Potatoes, a sheet that, despite its obvious limitations and uncertainties, manages to reveal the attitude of an artist who, in later years, would delve into the themes of daily life in the countryside, work, and the conditions of Dutch peasants. In parallel, the exhibition follows the formal developments of Van Gogh’s art: Woman Sewing with a Cat, which is only a month or two later than Woman Peeling Potatoes, demonstrates the tangible progress of Van Gogh’s pencil, while Still Life with Straw Hat introduces the audience to the first experiments in color, conducted under the aegis of Anton Mauve, who suggested that the artist begin painting.

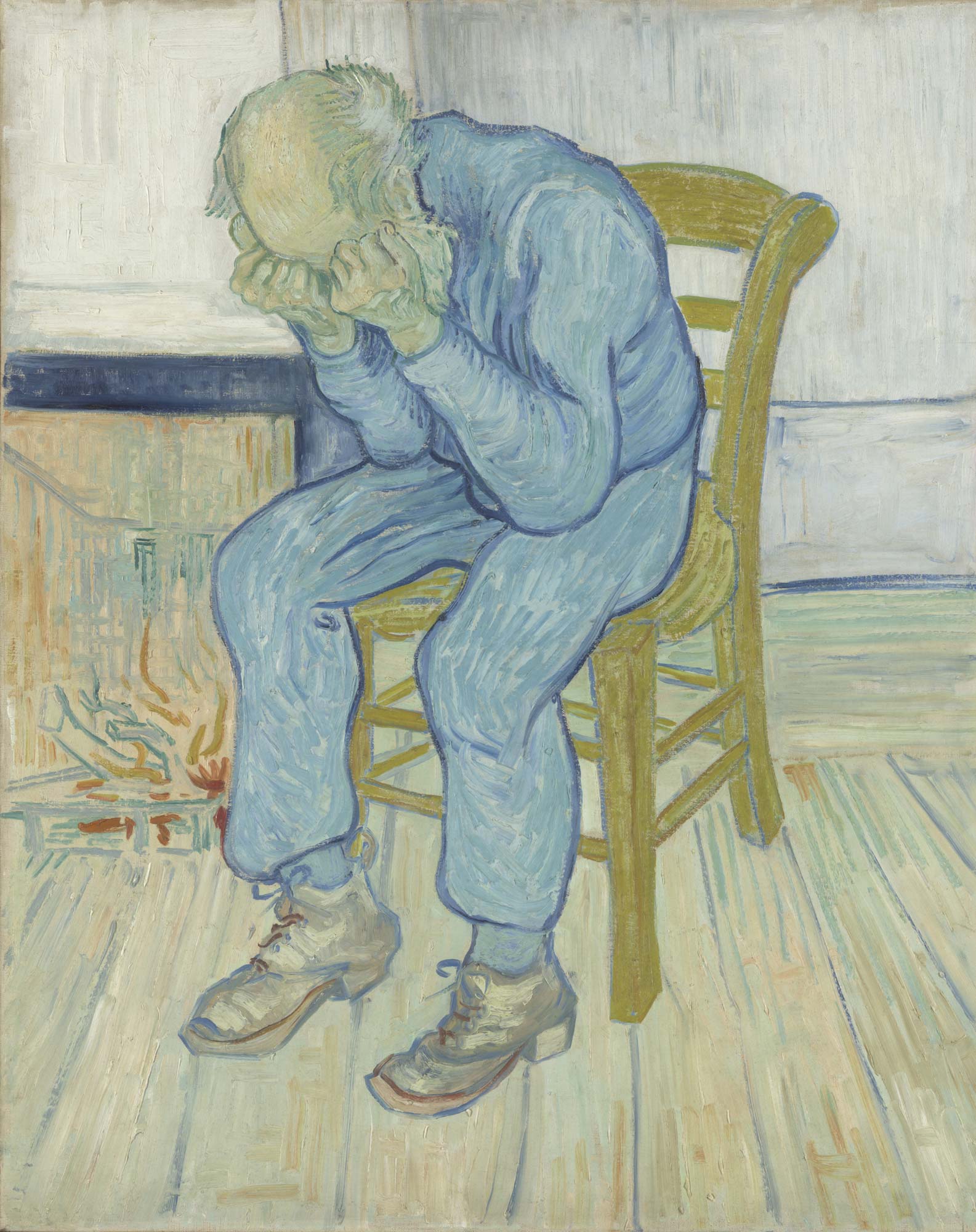

Toward the end of 1881, Van Gogh moved to The Hague: the curators place here a rapid thematic selection devoted to Clasina Christien Maria Hoornik, Vincent’s “Sien,” a meretrician he met in late 1882, with whom the artist would have an affair, abruptly broken off in September of that year because of... character incompatibilities, one might say by advancing an understatement (Van Gogh intended to redeem the woman from her dissolute life, but she evidently did not share this view). The drawing of Sien seated near the stove restores in detail the physiognomy of the beloved woman, who is here modeled for him: the drawing is vigorous, Sien’s presence is strong, intense, conveying a sense of a reposed and intimate monumentality. There is, on the other hand, a sense of tragic heroism in a watercolor from 1882 that recalls Van Gogh’s time spent in the Borinage, a poor region of Belgium known for its coal mines: the artist depicts some women standing, stooped under heavy sacks of coal, intent on strenuous labor that goes so far as to deny their humanity (we do not see their faces). And tragic, too, is the figure of the Suffering Old Man, another drawing exhibited in the same room, which would later be taken up, as we shall see, even in the extreme phase of the artist’s career.

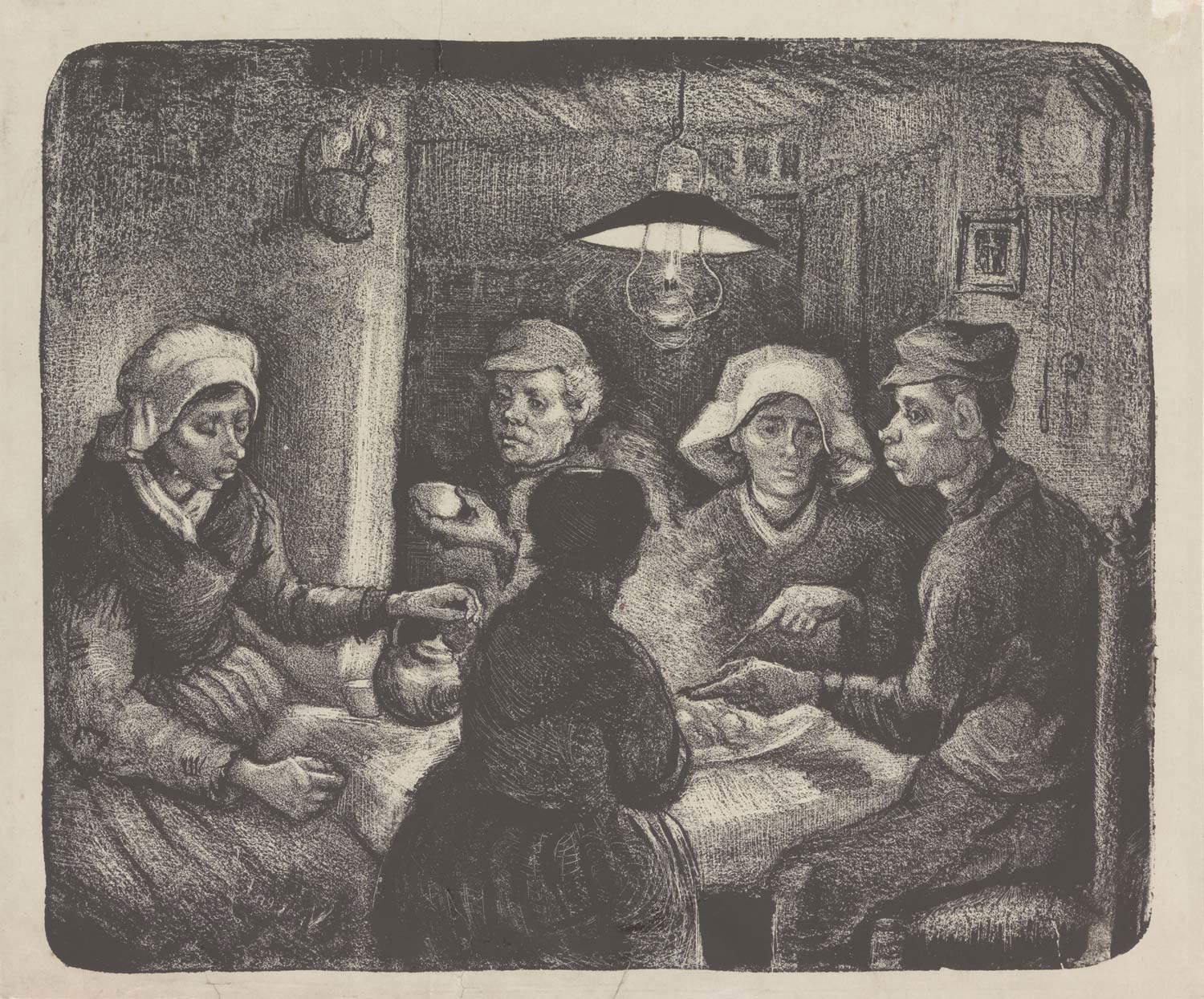

Instead, the move to Nuenen, a village where Vincent’s father Theodorus was working as a Protestant painter, dates from 1883. The outline of Nuenen’s old tower is painted in a canvas from the winter of 1884 (the tower would be torn down a few years later), which Van Gogh loads with references to life in the Dutch countryside: “I wanted to express,” he writes in a letter to his brother Theo dated June 9, 1885, “how those ruins show that for centuries peasants have been buried in the same fields they hoed when they were alive, I wanted to express that simple things are death and burial, as simple as the fall of a leaf in autumn.” The ideal of simplicity that Van Gogh aims to achieve through his art is expressed through works dedicated to local people: thus here is a Weaver with Loom that gives an account of the main activity of sustenance of the inhabitants of Nuenen, here is a group of Peasants Planting Potatoes (preparatory sketch for the first major commission Van Gogh received in his career, when the goldsmith Antoon Hermans asked him for some panels with which to decorate the dining room of his home, here are the intense female portraits such as the Head of a Woman with a White Bonnet, which offer a concrete example of how Van Gogh mastered by the date of 1884 the use of color and how he knew how to paint portraits characterized even by a certain psychological introspection. This brings us to the pinnacle of the Nuenen period, The Potato Eaters, which Van Gogh considered the best work of his Dutch period, and which is evoked in the exhibition by a lithograph taken from the first version, the one executed live, in the home of the De Groot-Van Rooij family, the peasants who posed for the artist around their dinner table. Before moving on to the next room, however, we dwell on Peasant Girl Harvesting Wheat and Peasant Girl Washing a Pot, which the exhibition introduces to closely follow the technical process of Van Gogh’s art: the figures, writes Villanti, “have strongly realistic connotations, from which the intention to create a scene imbued with truth is evident [...]. The composition is very similar, chosen to create a compact and extremely volumetric whole. Van Gogh treasures Delacroix’s working method, focusing more on volumes than contours. The painter works on sheets of tissue paper of the same size using charcoals with deep blacks and fixing the color with a solution of water and milk, evident in both drawings from the discolorations of the paper around the women.”

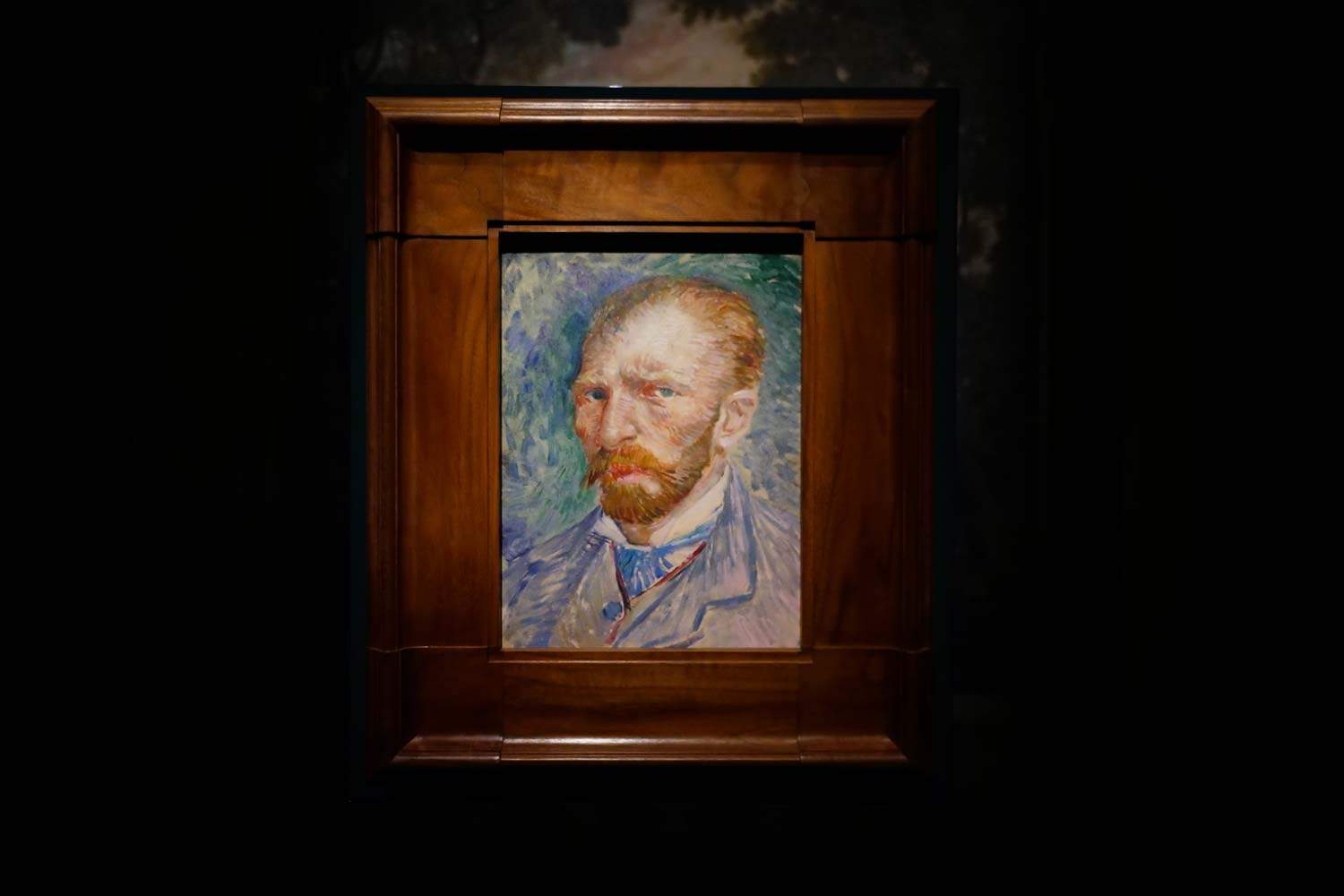

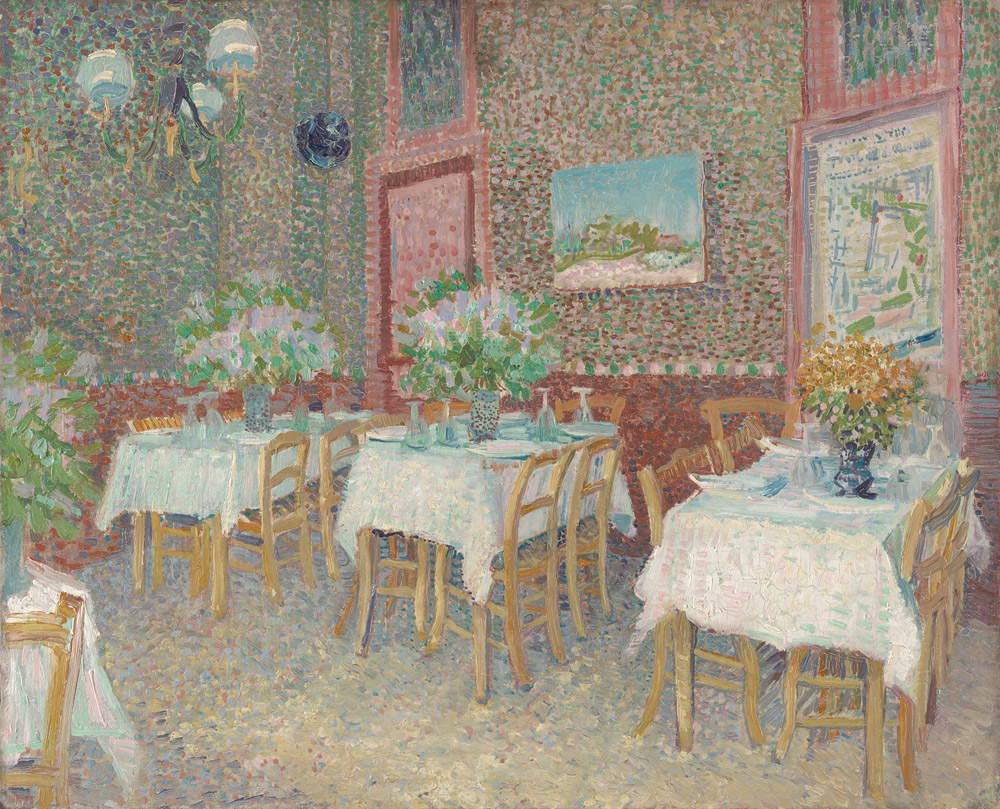

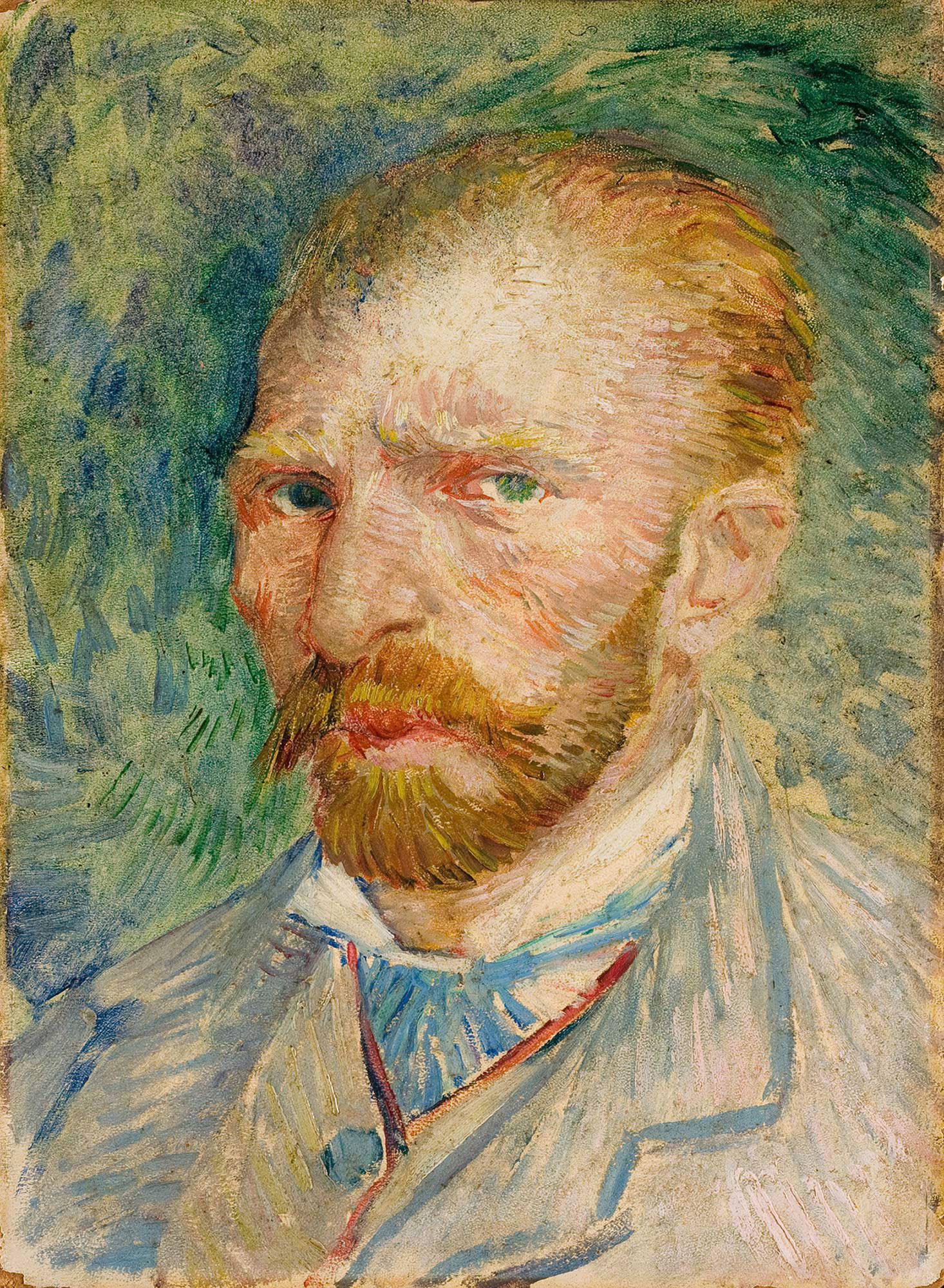

1886 was the year the artist moved to Paris. The stay, which lasted two years, is retraced with a small but significant number of paintings, beginning with the Hill of Montmartre, which testifies to the old appearance of the Parisian neighborhood, before total urbanization: it is a painting that still suffers from the palette, backgrounds and compositional schemes of the Dutch period, elements that would later give way to decidedly different solutions oriented toward modern painters. An example of this is theAngle of a Meadow, which looks to the pointillism of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac (with the latter Van Gogh had also befriended), and the same can be be said ofInterior of a Restaurant of 1887, a work in which the Dutch artist further experimented with the pointillist technique by looking for strong hues, studying the possibilities offered by color contrasts, and adopting an oblique compositional scheme, unprecedented for him, in order to render a summary of modern Parisian life. Already in Holland, Van Gogh had deepened his understanding of color theory by reading the treatises of Charles Blanc, a poet and art critic who had written a Grammaire des arts du dessin that was much appreciated by the Dutch artist: his impact with France gave him a way to deepen his research on complementary colors (the letters show how much passion the subject would arouse in him, and the exhibition devotes a focus to this theme). The second floor closes with the ParisianSelf-Portrait of 1887, to which the exhibition devotes an entire room. Forty self-portraits are known from the artist, who was firmly convinced that a painter who portrays himself performs an operation that no camera can do: “painted portraits have a life of their own that originates from the painter’s soul,” Van Gogh wrote in a letter to Theo in 1885, brought back by the exhibition in a panel that identifies the self-portrait as a kind of self-inquiry that Van Gogh would never stop operating.

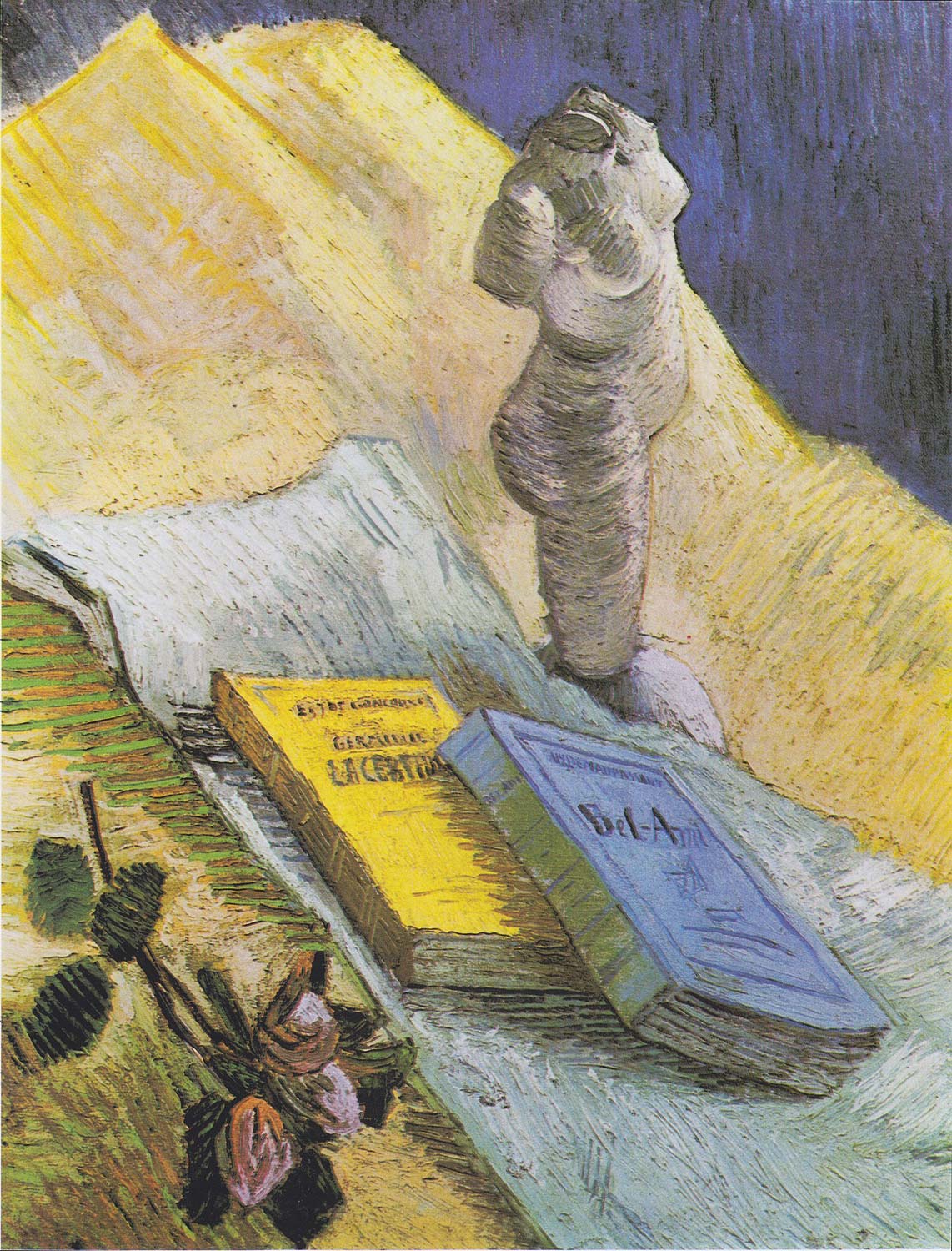

The first room on the upper floor recounts the move from Paris to Arles, with a number of works that straddle the 1887-1888 period displayed to demonstrate the variety of interests Van Gogh had at the time: the Flowers in a Blue Vase offers the curators an opportunity to emphasize Van Gogh’s debts to Adolphe Monticelli, an artist who has many elements in common with the great Dutchman (radical innovations, substantial isolation, lack of understanding on the part of his contemporaries), while the Still Life with Plaster Figurine, with its flat colors and oblique cut, stems from the artist’s passion for Japanese prints, of which, moreover, he was also a passionate collector. We come to Arles with the Basket of Lemons and Bottle: it was 1888 when Van Gogh moved to Provence, eager to impart an extreme change to his palette. Provence is Van Gogh’s Japan. The painter was burning with the desire to see live the light of the south and the warm colors of the Mediterranean, he wanted to renew his art by letting himself be carried away by the glow of those lands: thus, already in this Basket of Lemons, writes Benedetti, “one feels the sense of a new freedom,” a freedom also matured by the readings that freed him from the sense of sadness he was beginning to feel in Paris. And Monticelli is an artist who touches Van Gogh’s soulstrings because (and it is Van Gogh himself who writes this), “he dreamed of sunshine, love and joy, but he was always tormented by poverty,” and he had “a refined taste as a colorist, a man of rare breed who carried on the best ancient traditions.” And Arles, according to Van Gogh, was an ideal place for “artists who love sun and color.” The sun of Arles arrives alive and burning inside the Sower of 1888, a work in which the artist returns to the themes of the Dutch period, but with a renewed awareness, with the idea that color can be the key to a new and untried expressiveness, with a strength and poetry that the artist pours even into the most ordinary, for example in the portrait of Lieutenant Millet, where Van Gogh unleashes an energy hardly seen in previous portraits, even cloaking it, according to Villanti, with an unusual sacredness, a sense of transcendence that goes back to the primitive Sienese.

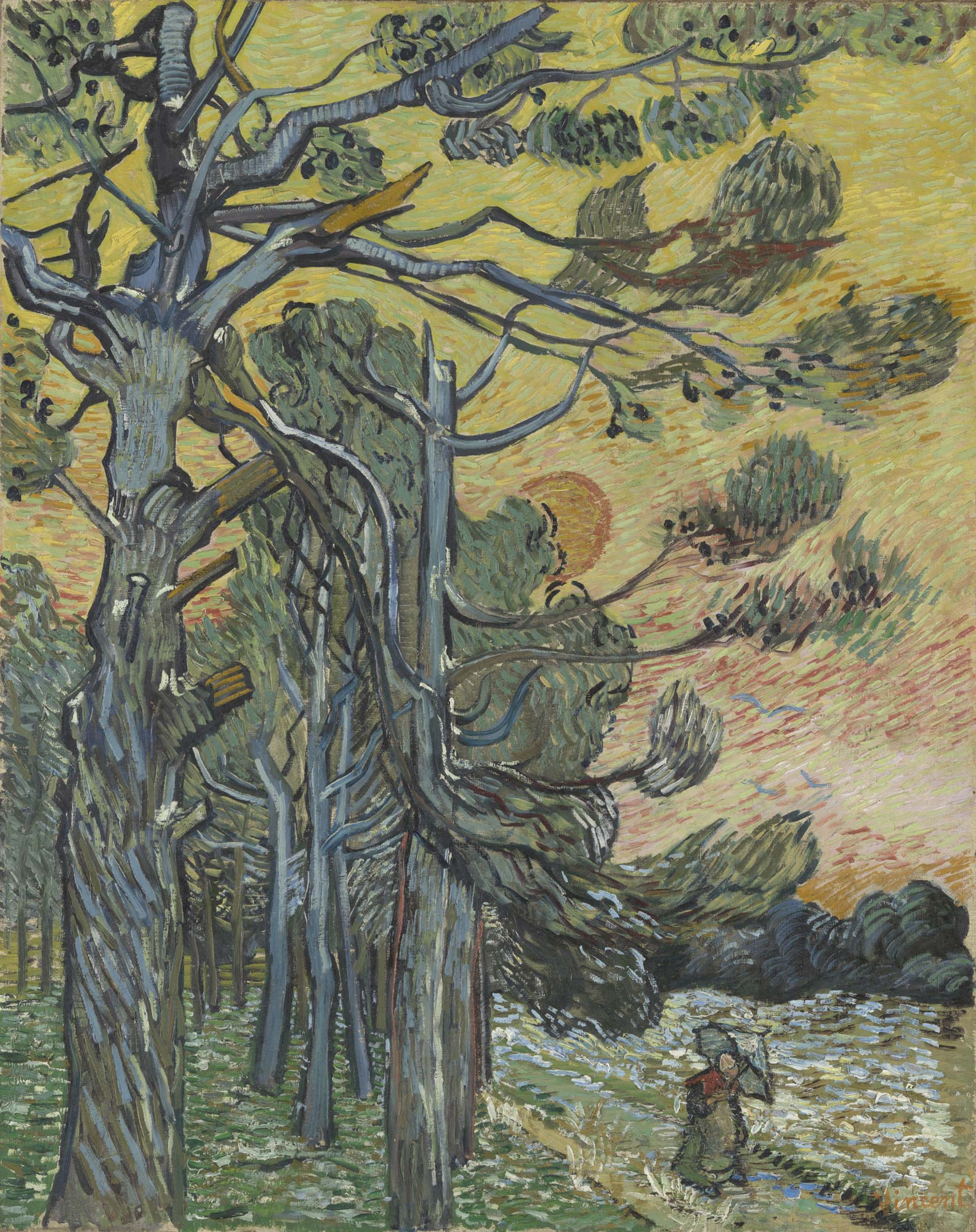

The happy period in Arles, however, is destined to be short-lived. Not even a year and a half, and in Van Gogh the signs of a profound psychic distress manifested themselves, leading him to be hospitalized at the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole nursing home, near Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. The period of his hospitalization is well represented, in particular, by two works. The first is The Garden of the Asylum at Saint-Rémy, a work from May 1889, thus dating from the first month of his hospitalization: Van Gogh looks at the world through the window of his room, the illness fills his eyes and causes him to see reality as he had never before seen it, everything becomes more intense, more vivid, more charged, more violent. In The Garden of the Asylum one senses the prodromes of what was to be the last Van Gogh, and an even more obvious sample is offered by the second work, the Pines at Sunset, painted in December of that same year, when the artist is given the option of leaving the hospital to visit the countryside. Van Gogh’s mind leads his hand to paint an altered reality, but a clear lucidity shines through the letters: “I got up,” the artist writes to his sister Willemien about the Pines, “to go and give a few brushstrokes to a canvas I was working on-it is precisely the one with the twisted pines against a red, orange and yellow sky-yesterday it seemed very innovative, the tones pure and ringing, well, writing to you, I don’t know what thoughts came to me and, looking at my painting again, I said to myself that it was no good. So I took a color I had on my palette, some opaque, off-white, which is made by mixing white, green and a little bit of carmine. I added this tone of green all over the sky, and lo and behold, looking from a distance, the tones softened because they were broken up.”

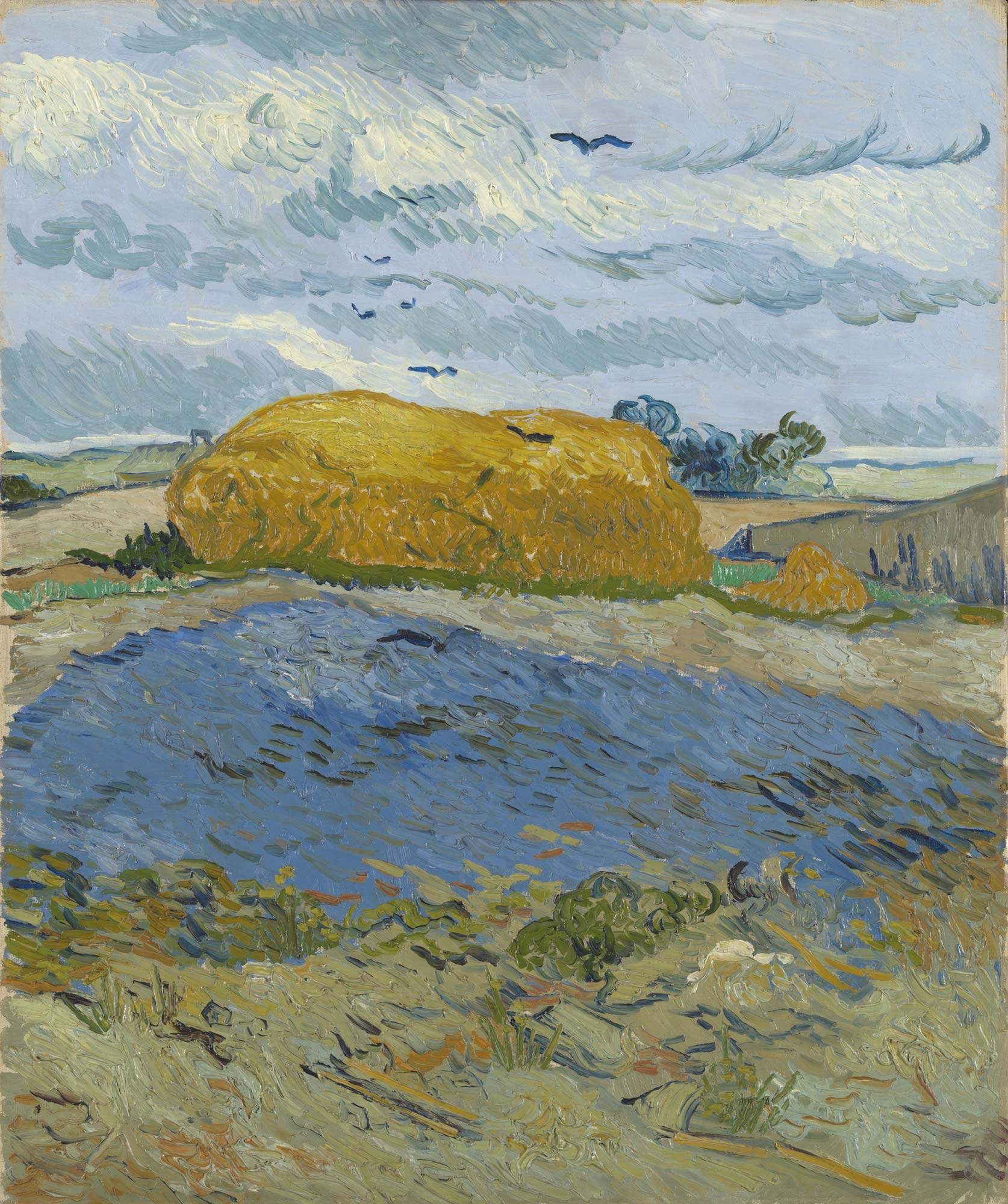

Van Gogh realized that painting was good for him, and in the moments when his illness gave him respite he tried to get permission to devote himself to his activities, never impulsively, but always meditating on his research: evidence of this is the Sower of 1890, his last experimentation with his beloved Millet. His resignation came in May 1890, the time to which dates the Desperate Old Man with which the exhibition closes, a reworking of the drawing dating from the Etten period exhibited at the beginning of the itinerary, and a manifestation of his suffering that the public has a way of perceiving and touching as early as the penultimate room, observing the Sheaf under a cloudy sky, which is not charged with the tormented anguish of Wheatfield with Flight of Crows (the Van Gogh Museum painting that is perhaps the most famous of the last phase of the artist’s career and life), but is equally able to convey the same sense of despondency, loneliness and sadness that the artist felt at the end of his life. The storm and crows fluttering beneath the fields become ominous omens of what was to come shortly thereafter: Vincent van Gogh shot himself in the chest on July 27, 1890, and died two days later.

The exit to the bookshop is accompanied by the audio of an avoidable and sloppy narration by the now ubiquitous Constantine D’Orazio about Van Gogh’s last days: it is a surplus that could easily have been avoided and that the audience can overlook without regret, not least because following the narrative set up by Benedetti and Villanti is frankly challenging (one will arrive at the end of the tour surprised at how it was possible to spend a couple of hours in an exhibition of only forty paintings). This is because the exhibition is continually enlivened by lateral insights that induce one to return to the works, to move away from the mainitinerary, to reason about the drawings and paintings by following the many traces left by the two curators and educational project leader Eleonora Luongo: for example, the public is offered, as anticipated, a long parallel narrative on Van Gogh’s “artistic evolution” (so the panels), which makes continuous lunges into the artist’s technique, the materials he used, his color choices, and even the punctiliousness with which he conducted his formal research (it will be discovered, for example, that in Arles he had his colors sent directly from Paris). All of this always following the lead of his writings, as when the transition, between Holland and Paris, from imitative to evocative color is emphasized: “It doesn’t matter if my colors are exactly the same as those of nature, as long as they look good on my canvas, just as they look good in life.” Even, some panels call for the direct involvement of the visitor, invited to touch the apparatus to make comparisons between Dutch and French colors, or to discover how the artist applied complementary hues, through direct examples that can be verified on the works in the exhibition. A commendable didactic effort as well: this too is talking to the public so that something remains.

Some misgivings may be advanced about Art Media Studio’s installation The Starry Night, which the audience encounters before the exhibition finale: it can still be considered an entertaining pause before heading to the concluding rooms (at least, however, in Rome there is no model of the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole clinic that the Vicenza audience had to put up with in 2017, which moreover plunged into the middle of the path and was unavoidable: at Palazzo Bonaparte, however, the installation is rightly separated from the path). Finally, good is the catalog, designed especially for a wide audience: In addition to the curator’s reconnaissance mentioned above, to the worksheets (all with an essential bibliography and selected exhibitions, which is not taken for granted in a catalog of an exhibition on Van Gogh, just as it is not taken for granted that there are the worksheets either) and a contribution by Francesca Villanti on the origins of the Kröller-Müller, there will be two essays, one by Marco Di Capua and one by Mariella Guzzoni, respectively on Van Gogh’s letters and the books the artist read, to provide the public with an overview of the artist that may not be complete but is certainly much more truthful than what has emerged from so many hasty and shoddy operations on Van Gogh. At the Palazzo Bonaparte, however, an exhibition has been mounted that goes beyond the logic of the usual box office exhibitions, the usual “blockbuster exhibitions,” and even with the limitations imposed by the need to have works coming from a single collection (which is still the second largest collection of Van Gogh in the world, so much so that the Kröller-Müller, even depriving itself of the works lent to the Bonaparte Palace, has no problem with underrepresentation, but it is still a single collection) manages to create a worthwhile product, a cultural operation to look forward to.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.