Men who dressed as women in the U.S. of the 1960s: the exhibition on Casa Susanna

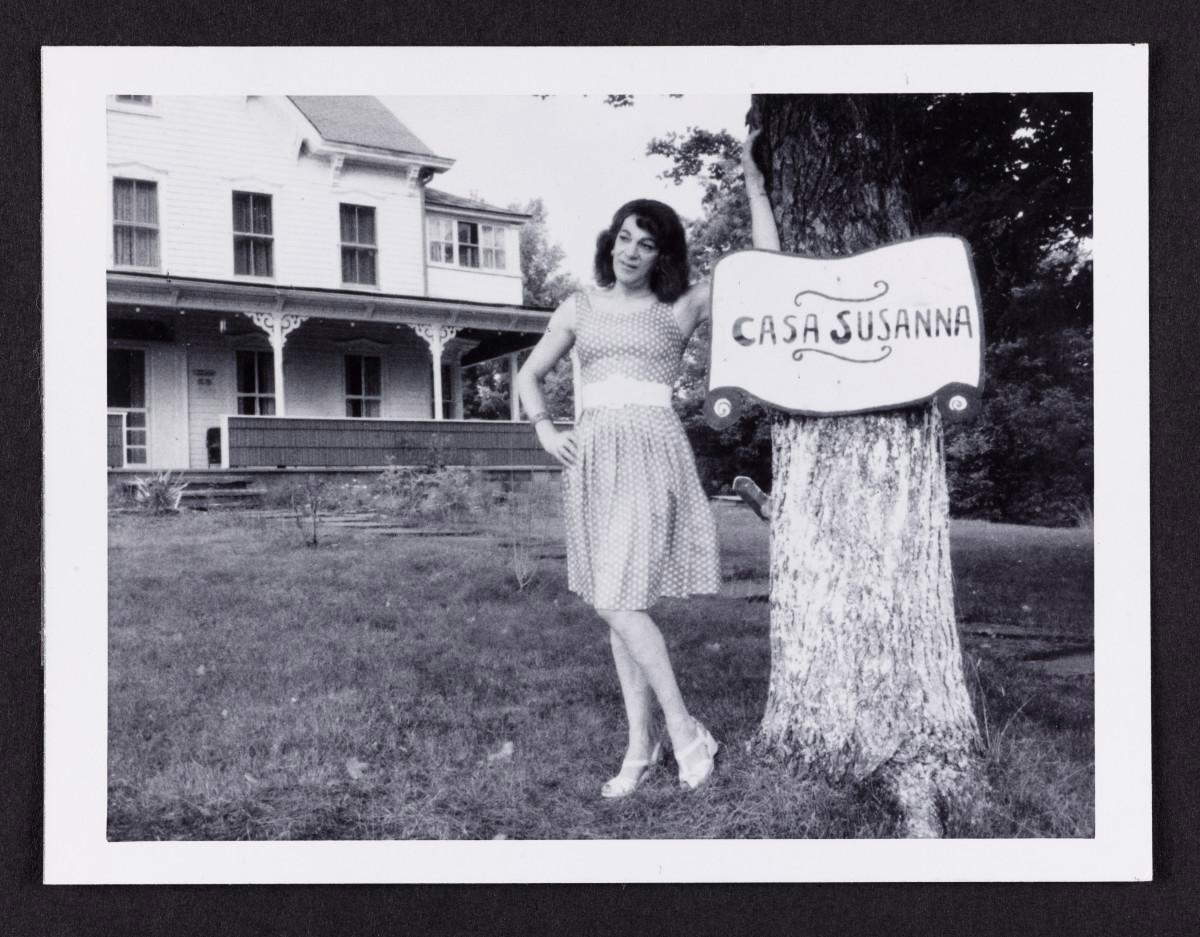

Welcome to Casa Susanna. In the photograph, this name is roughly engraved by hand on the trunk of a tree, in orange. But in another it appears on an actual sign. We see the two images in Arles, France, at theEspace Van Gogh exhibition halls, which catapult us to the United States between the 1950s and 1970s, a two-hour drive north of New York, in the Catskill Mountains. The house, a main building with a garden and other small cottages, is the place that gives its title to the exhibition(Casa Susanna, in fact) curated by Isabelle Bonnet and Sophie Hackett, and to the accompanying book, published by Éditions Textuel. The exhibition is on view in the museum named after the master of sunflowers, from July 3 to September 24, 2023, as part of the fifty-fourth edition of Les Rencontres de la Photographie festival, which produced it together with the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO).

The magic of photography makes materialize worlds distant in time and space, distant from the eyes, and yet so close because of having them in front of us, visible. Its documentary value of witnessing is particularly significant when, as in the case of the valuable exhibition at Rencontres, it allows us to discover, and see, a hidden and in some ways clandestine history, an experience that without the camera lens would probably have remained unknown. Thus in Arles we have the extraordinary opportunity to enjoy the extraordinary newfound images of Casa Susanna, which in 2004 two antiquarians discovered and purchased in a New York flea market and which later became part of several collections. The exhibition brings together for the first time the AGO’s collection, Cindy Sherman’s personal collection, and Betsy Wollheim’s personal collection.

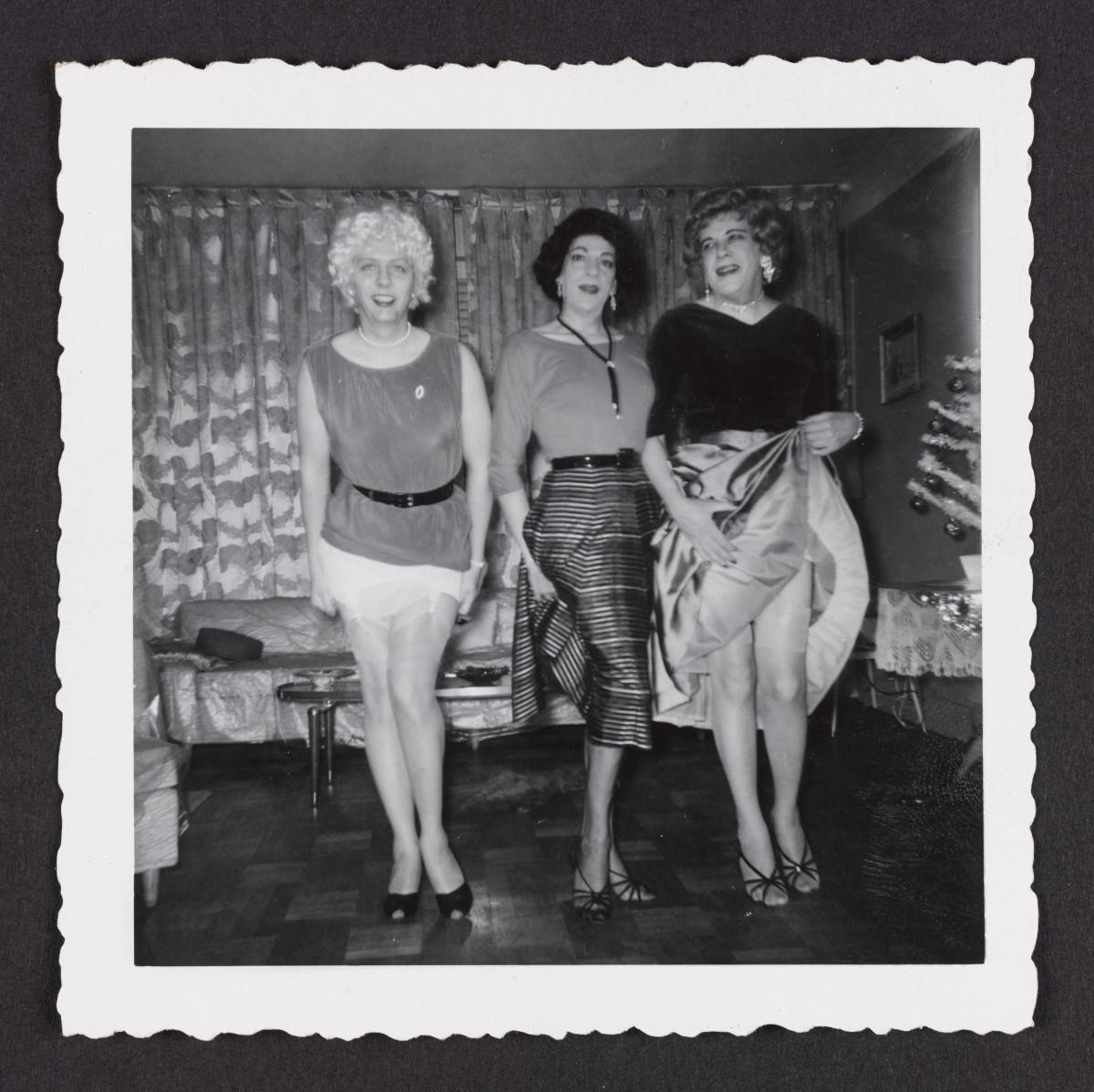

What was special about these prints? They were all portraits of men dressed as women, in a constructed identity as respectable housewives, no excess in clothing. In the exhibition rooms we are greeted by mostly small-format photos, but also reproduced blow-ups, of these elegant, well-dressed ladies who seem to invite us into their homes and into their world to tell us a story. And what a story it is. Let’s sit on the couch and listen to them: they were part of a vast hidden network of “cross-dressers” who all met, precisely, at Casa Susanna. This is how the curators define them, who are keen to specify that this is a different concept from that of transvestites or transsexuals: “In their day, the cross-dressers at Casa Susanna called themselves ’transvestites’ or ’TVs’ for short. This term is now considered pejorative and we have avoided it wherever possible. In French, however, the only term available is ’travesti’. We have used it here both for historical accuracy and because most members of the Casa Susanna network made a clear distinction between their cross-dresser and other trans identities.”

Who were they? Men, white, middle-class American husbands and fathers with even prominent jobs, among them engineers, pilots, even civil servants who liked to dress as women in an America at the height of the Cold War that repressed and condemned transvestites and homosexuals because they violated the norms of the time. Gender differences were branded as deviances to be fought: the main target was homosexuals and cross-dressers, who were considered sick to the point of subjecting them to treatment that was closer to torture than psychiatry. “As historians,” Isabelle Bonnet and Sophie Hackett further specify, “we have tried to strike a balance between the facts, the ways in which individuals in the Susanna House circle self-identified, and our contemporary awareness of a spectrum of gender identity. Therefore, in our view, this community represents the first known trans network in the United States.”

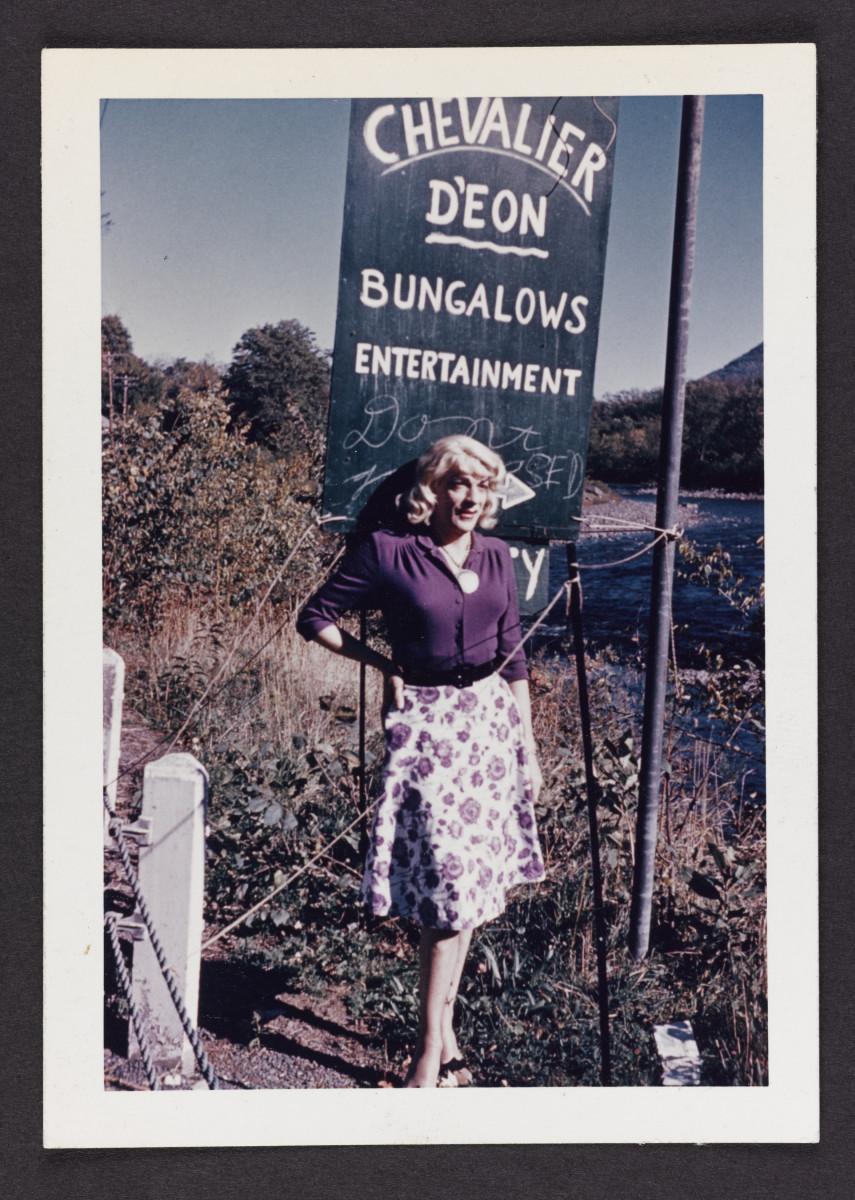

Thus, Susanna. Born Humberto (Tito) Arriagada in Santiago, Chile in 1917. At age 21 he came to the United States to attend college; in 1940 he joined the U.S. Army employed by the propaganda radio station Voice of America. He married Marie in 1958 and it was she, his wife, who opened the doors of his house in the green to Susanna’s cross-dressing friends. Between 1959 and 1968 this group gathered in that place safe from prying eyes, a network of relationships organized around the underground magazine Transvestia. This experience offered many people the chance to no longer be alone in their desire for cross-dressing. Susanna, but also Virginia, Doris, Fiona, Gail, Felicity, Gloria and their friends created a unique collective identity despite the serious risks they were taking. In the exhibition, the curators also provided the stories of some of the protagonists of the rediscovered photo gallery. Susanna and Marie named the venue “Chevalier d’Éon” in honor of the notorious French diplomat, a spy who secretly worked in the direct service of King Louis XV and lived the first half of his life as a man and the other half as a woman.

Images rediscovered. The world of photography is discovering in recent years some stories that remained locked in trunks for decades. Think of the Vivian Maier case, a compulsive shutterbug nanny whose hundreds of negatives and rolls of film still to be printed were only found a few years after her death in an antiques market, just like the photographs set in Casa Susanna. Or the recent return to light of the history of Italian Alberto Di Leonardo, whose talent in more than 10,000 photographs was unveiled at the behest of his granddaughter after her grandfather’s death.

However, this one we see at the Espace Van Gogh in Arles is a different case, in which it is not so much the talent or the eye of the photographer that counts (the protagonists immortalized each other) but, we reiterate, the facts that these snapshots of life tell and their glances as it were crossed that nonetheless give rise to remarkable images. More than fifty years on, the exhibition now has the merit of restoring to cross-dressers the dignity, freedom and smiling beauty that the intolerable rules of the time had mortified. To visit it is to give oneself an opportunity to feel part of the events, desires and vision of a small community that left an important testimony, not only on a historical and sociological level, but also on a visual one. The model for the images were the advertising and fashion photographs published in magazines such as Good Housekeeping, Ladies’ Home Journal but also Vogue.

So what do we observe in these shots that to demote to amateurish would be reductive? Portraits, mostly full-length and with different sets, both in black and white and in color. In those in color, one appreciates more the attention to color harmonies, to combinations. In the documentary film directed by Sébastien Lifshitz, an important document complementing the exhibition of which it bears the same title, there are the protagonists themselves telling their stories in the first person. Returning both in memory and physically to Casa Susanna, they recall how guests in the cottage would spend up to four hours in the bathroom getting ready. They would only come out when they were fully satisfied with their transformation into women’s clothes. And the smiles turned to the lens speak volumes on the subject of happiness.

The focus on outfits tells the whole story of fashion in the years between the 1950s and 1970s in this roundup of images. Femininity is the watchword, as are the always hyper-coordinated looks where pastel colors prevail. Knee-length skirts with minimal sweaters or light blouses tucked in, as well as fitted or bell skirt dresses. Stiletto heels being invented in those very years and handbags, small, usually with a handle held by hand or on the wrist, almost always matching the shoes, are almost never missing from the photographs. Wigs with very similar cuts, bobs with short bangs, straight hair or with waves, some have ringlets. There is the whole variety of hair colors as well as special attention to costume jewelry as well, pearls being the main feature. And again, portraits in swimsuits, undergarments and guêpières, the ultimate expression of transformation into a woman.

And then, in the background, the real protagonist, the home. Place of refuge and freedom. The kitchen, the living room, the garden. The Christmas tree, the sofa, the glass coffee table, the chairs, the television, the swing: all the surroundings contribute to making that experience integrated into the everyday of a common life. Photographs are prepared, real sets are created to capture those moments of freedom and happiness. An imaginary stage where the protagonists can perform in their most beautiful and beloved clothes, which is sometimes symbolized precisely by a curtain that can be seen in the background of the photos, like an ideal theater, a metaphor for that parallel life that the guests of Casa Susanna had the illusion of living freely. Every year Susanna and Marie organized a Halloween party, the only time when cross-dressers could dress up even in public without incurring risks.

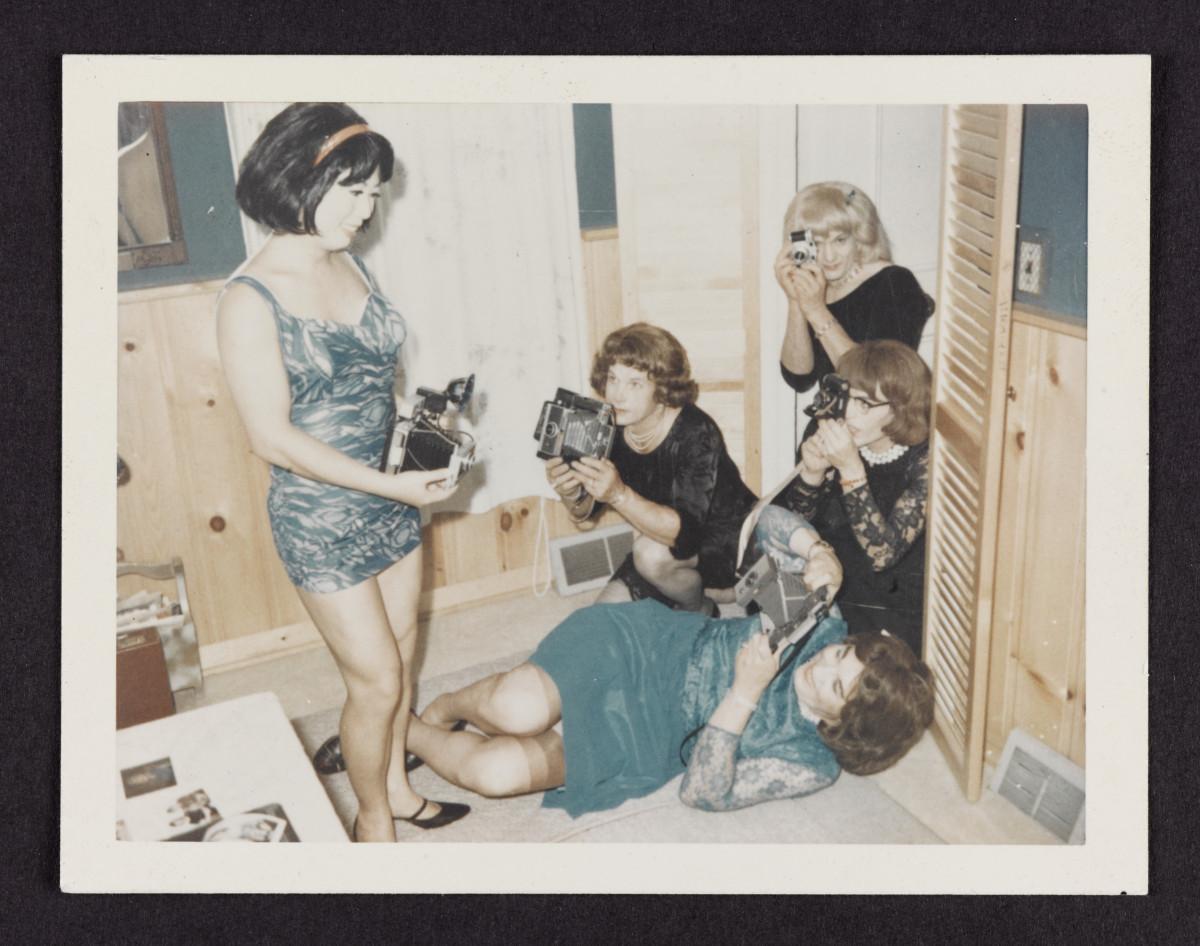

Moving through the halls of Espace Van Gogh and the pictures we jump from season to season, through the different outfits, the snow, the changing light: men dressed en femme laughing, having fun, gardening, playing Scrabble. In addition to the photos, there are several sections in the exhibition devoted to Transvestia magazine, the cross-dressers’ link. Susanna Says was the name of the landlady’s regular column. Photography was a key part of the publication. We saw it: between them they were taking them, making copies and keeping those of themselves and those of others. When at some point there was the possibility of having a Polaroid camera, it made the problems related to printing and duplication much easier.

Several covers were on display. All decorated with a lace design belting the page vertically on the left until it disappears into the spine. Top title with font that changed color to match that of the frieze. White background and central photo (a portrait). The first issue of the magazine, founded and edited by Virginia Prince, was published in 1960. And from there it went on for six issues a year of about eighty pages each until 1986. Transvestia was sent clandestinely by mail. It contained fiction, autobiographical articles, poems, clothing and make-up tips, and, most importantly, photographs. Before the magazine, most cross-dressers lived in total isolation, in secrecy and shame. So distribution functioned as a kind of forerunner of social networks, creating a small, safe community.

On the cover of the book Casa Susanna. L’histoire du premier réseau transgender américan 1959-1968, edited by Isabelle Bonnet & Sophie Hackett published by Èditions Textuel, are the protagonists of this incredible story with cameras in hand. Photography was the only means of bearing witness to that experience that served yes for the magazine, but it was essential for them above all, to remember that that “dream” had really happened. It is thrilling to see, thanks to the film, the moved eyes of some of them after more than fifty years flipping through the prints and recognizing themselves and others in that moment. “But that can’t be me!” one interviewee who has become a woman exclaims in favor of the camera. And yes, it is indeed her, because the photograph stands there to testify to something that cannot be refuted in this case.

Casa Susanna no longer housed anyone after Marie had a serious accident in 1967, and after the house was sold in 1972. Singular that the cross-dressers’ oasis dematerialized in the same year that Lisetta Carmi ’s book I travestiti was published in Italy, which booksellers refused to display because it was too scandalous for the morals of the time and was therefore withdrawn, destined for the scrap heap. The social survey reportage on the community of “transvestites” (to recall the title at the time) in downtown Genoa, of which Contrasto in 2022 published a new edition with the hitherto unpublished color photographs that, mutatis mutandis, are so reminiscent of those exhibited in Arles, was made between 1965 and 1972. Journalist Stefano Ciavatta points out that, elsewhere in France, just two years before the start of the meetings at Chevalier d’Éon, "between 1956 and 1962 the 40-year-old Swedish photographer Christer Strömholm made Les amies de place blanche, a reportage that was the result of a long and participatory frequentation in the Place Blanche neighborhood of Paris, the equivalent of the transvestite ghetto in Genoa. [...] It will only be published in 1983 and in Swedish."

In 1970 Susanna signs her last column in Transvestia without giving any further explanation. And then she writes again for the very last time in 1979 claiming that cross-dressers had not achieved liberation and that trans identity was still taboo. No one knew that Susanna had had to live full-time as a man to support his wife, who was severely disabled after the accident. “Love, Susanna.” Thus she bids farewell to her audience, and to us, visitors to the exhibition who reluctantly leave her home.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.