It was November 21, 1881, when Pierre-Auguste Renoir wrote his dealer Paul Durand Ruel a letter from Naples imbued with melancholy doubts, uncertainties, and deep awareness. Awareness of which only great artists and the most humble minds eager for discovery are capable. “I am still sick with research. I am not satisfied, I erase, I keep erasing. I hope to get rid of this mania [...] I don’t think I bring back much from this trip. But I think I have made some progress, as always happens after long research. You always go back to the first loves, but with something more.” And this is precisely the premise that accompanies the visitor through the rooms of Palazzo Roverella in Rovigo for the grand exhibition, curated by Paolo Bolpagni, Renoir. The Dawn of a New Classicism, whose goal is to show, with totally new eyes, a little-known side of the artist by shaking off the sweetened and at times cloying patina that has often conditioned the judgment of his art.

Although the premises may seem very similar to the 2008 Rome exhibition curated by Kathleen Adler, Renoir. Maturity Between Classic and Modern, which aimed to recount the changes in style and worldview in the artist’s oeuvre especially through his maidens, the Venetian retrospective succeeds in taking the viewer on a journey through the eyes of the French artist by juxtaposing works by Italian masters with the protagonist’s own work. And wandering through the rooms of the Palazzo Roverella, one admires precisely Italy as seen by a now wise Renoir who discovers Carpaccio and Tiepolo, admires Titian and reevaluates a Raphael previously so hated because of too many altarpieces studied at the Louvre. By juxtaposing these two poised souls, which almost seem to clash with each other, the artist identifies a new classicism that, instead of capturing the ephemeral typical of the Impressionist lesson, reveals figures out of time and space, in a rarefied but real and living world. The artist who for many years painted en plein air and who should have known, more than anyone else, about light and its changing being, recognized in Raphael the master of light who had never painted outdoors, but who was able to restore its freshness better than anyone else.

The trip to Italy, for the Frenchman, represented the definitive break from the circle of Impressionists whose anti-passatist attitudes he had never shared, although in 1877 he railed against the training of artists and architects at the École des Beaux-Arts who had “the ambition to imitate Raphael,” and this in his eyes made them profoundly “ridiculous,” as he recounts in his own text that appears in the collection Letters and Writings published in 2018.

Driven by a desire to know, discover and invent something new while avoiding unimaginative tracing of the past, between October 1881 and January 1882, Renoir set out to discover Italy. His journey begins in Venice, passes perhaps Padua and certainly Florence, then it is the turn of Rome, Naples, Calabria and Palermo.

The travels are described by the painter himself in his letters, where he says, “I suddenly decided to leave and was seized by an eagerness to see Raphael. I am therefore about to devour my Italy. I have seen beautiful Venice, etc. etc. I will start from the north and travel the whole boot while I am there. [...] For museums go to the Louvre. For the Veronese go to the Louvre. That leaves Tiepolo, which I did not know. [...] Venice is beautiful, beautiful lagoon, when the weather is nice. St. Mark’s, Doge’s Palace, stupendous the rest.” Reading excerpts of letters from the exhibition’s catalog allows us to discover a Renoir now in his 40s moved by the eagerness and need to see typical of a young boy. So the artist visits churches, galleries and palaces and, as the curator writes, discovers “the clear sign and the brilliant, full-bodied colors of Vittore Carpaccio, the magnificence of Tintoretto and, indeed, the terse, luminous vaporousness of Gian Battista Tiepolo.”

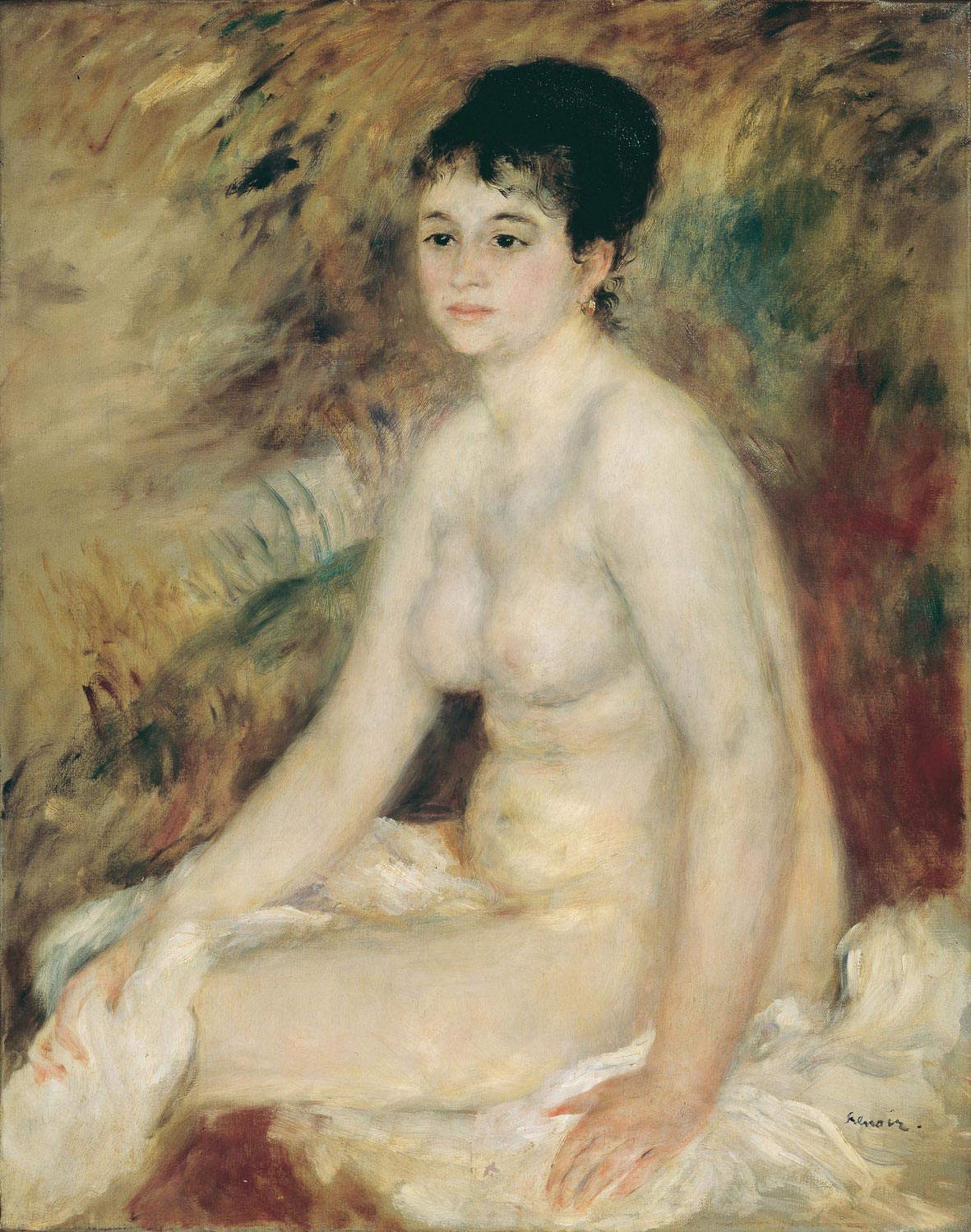

The Rovigo retrospective opens with two masterpieces from Renoir’s Impressionist season, taking visitors by the hand to discover the other side of the artist, without risking minor traumas from the very first room. The exhibition begins with the typical instances of the “Cooperative Society of artists, painters, sculptors and engravers, with variable capital and members” created in 1873 and led by Camille Pissarro. In the first room, the Impressionist Renoir heads unrivaled with two well-known works such as Après le bain of 1876 and Le Moulin de la Galette of 1875-1876, present with a study.

Several Italian artists worked in Paris during that same period, such as Giovanni Boldini from Ferrara, Giuseppe de Nittis from Puglia, whose last, unfinished work depicting his wife and child also appears in the second room, and the highly sensitive Venetian Federico Zandomeneghi, who turns out to be closest to Renoir in terms of the gentleness of his strokes. Those who would find a different climate in Paris would be Medardo Rosso, who would settle in the city later, in 1889, but did not feel distant from Impressionist pursuits. It would be he, first, who would try to evoke in sculpture the rarefied atmospheres of a constantly changing light through an almost sketchy modeling of the surface, with elusive contours.

During his trip to Italy, Renoir learned to capture the essence of figures by paying more attention to volumetries and monumentality, and once back in France, the boyish enthusiasm was succeeded by a profound crisis and he realized that he had to become familiar with drawing, which he had so disparaged up to that time. Drawing, previously absent, now returns to solid importance, providing the artist with enough structure to create an ante litteram“return to order,” a new unmistakable language between the ancient and the modern. A new style, sandwiched between volumetries borrowed from Raphael, Perugino, Tintoretto and then liberated by his brush at once gentle and bold.

In Italy he read Cennino Cennini’s The Book of Art, thanks to which he rediscovered the importance of history and school. For the curious artist, this book would be the main cue to undertake experiments with colors, binders and brushes, and he was so fascinated by it that he wrote the introduction for the French translation reissued by Victor Mottez’s son, from which we read, “Cennini’s treatise is not only a technical manual: it is also a history book [...] which acquaints us with the lives of those elite artisans thanks to whom Italy, like Greece and France, acquired the purest glory. I insist: it is the works of the many forgotten or unknown artists that make the greatness of a country, not the original work of a genius.”

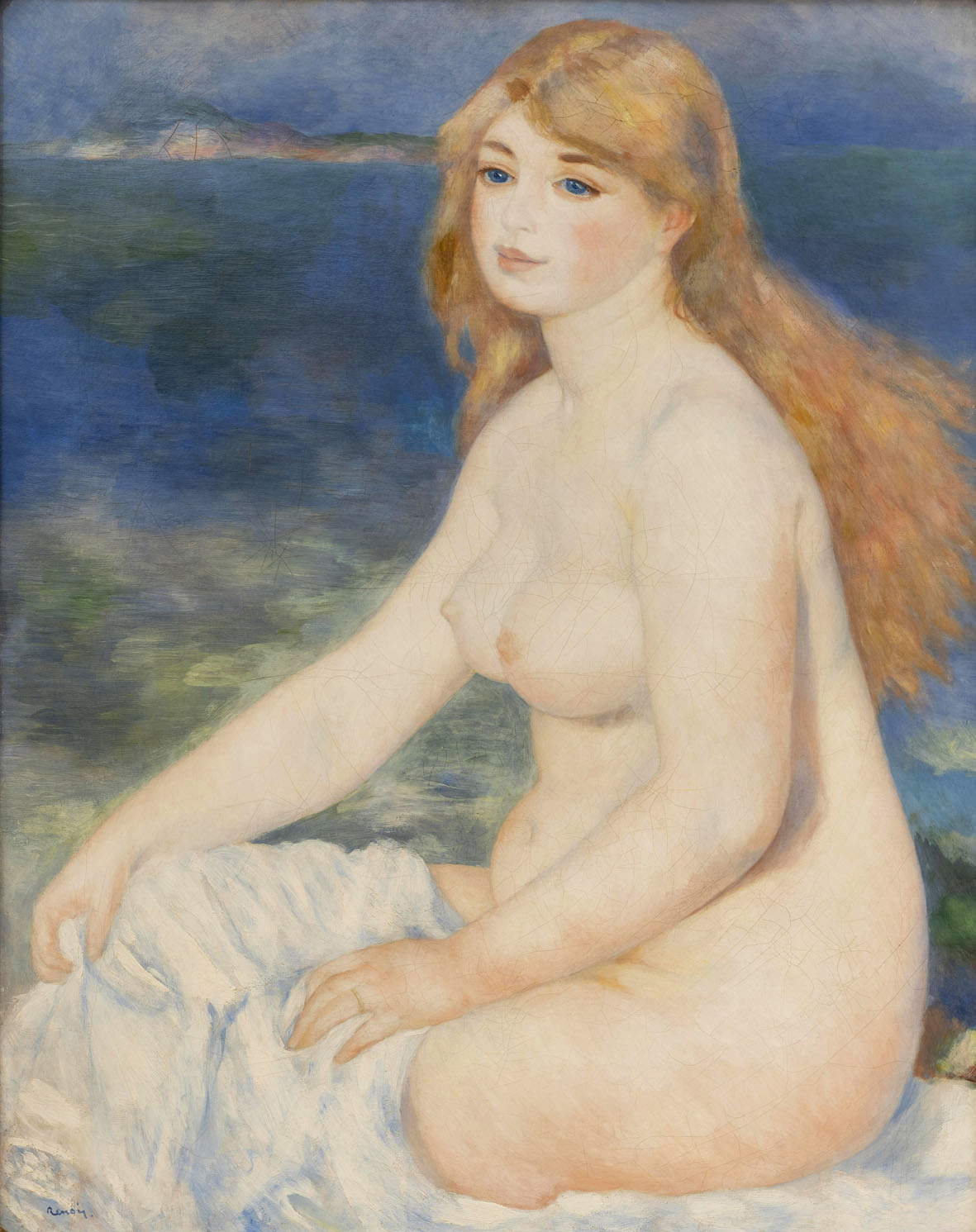

The next salon describes precisely “Renoir’s early rethinking of Impressionism” starting with the rediscovery of drawing through, above all, the delicate graphites of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and the book, quoted earlier, by Cennini, which turns out to be a true revelation for the artist. A key destination of the pilgrimage is Rome, where he is overwhelmed by the boundless Mediterranean light and the Renaissance masters, except for the “too many muscles” of Michelangelo. But it is Naples, Sorrento and Capri where Renoir discovers his Italian roots, becoming fascinated by Pompeian paintings. Italy was the harbinger of a profound and painful creative revolution that culminated in his final abandonment of Impressionism, and part of this separation is recounted in the 1882 work La baigneuse blonde. Renoir portrays his future wife Aline Charigot as a modern Venus with skin of the most fragile porcelain and a diaphanous complexion in front of a sea of an intense blue that, according to the artist, should be that of the Bay of Naples as seen from a boat. The enchanting woman seems to be the keystone of a temporal short-circuit that absorbs the essence of Pompeian art and Raphael’s frescoes at the Villa Farnesina in Rome. Lines are transformed and become sharp, full volumes, monumental figures and contours, usually nonexistent in the artist’s works, are discovered sharp and he begins to create textural and ethereal bodies of timeless beauty with a new focus on drawing and the sinuous lines of existence. The Venus is juxtaposed with two drawings by Renoir and two by Ingres both characterized by this “return to craft,” to use the term that, later, Giorgio de Chirico would coin to talk about his own art. Italian sources also stand out here, such as Vittore Carpaccio’s mixed-media panels of 1485-1490 depicting St. Catherine of Alexandria and St. Dorothy, but also Titian Vecellio’s Madonna and Child of 1560-1565 and Gian Battista Tiepolo’s 1743 canvas Abraham and Angels.

The desire that prompted Renoir to leave for Italy matured not only from the artist’s irrepressible desire to study live the very works that Ingres and other academic painters had elevated to symbols of perfection, but also from the financial crisis that touched France in 1873.

The economic collapse, as was obvious, mainly affected what was not essential to life, such as art, and Renoir encountered serious difficulties. As art historian Giuseppe Di Natale explains in the exhibition’s catalog, the artist decided to reach a wider audience by returning to exhibit at the Salon from 1878 and disavowing his past as an Impressionist, feeling a deep embarrassment for it and prompting him to implement true self-revisionism. Renoir thus gave birth to an art that anticipated that which would spread overwhelmingly in the aftermath of World War I with a return to the classical artist’s craft. From here the tour continues in the room of “modern classicism: ancient myth and the bathers,” in which the artist was fascinated by ancient tragedy and created Pompeian rehearsals of some characters from Greek mythology that would later be purchased by Picasso.

In this room, Mediterranean classicism is also reproposed by the monumental bronze Venus holding the apple of victory modeled by Catalan assistant Richard Guino under strict instructions from a Renoir now overcome by arthritis. The latter dialogues with Marino Marini’s 1938 Classical Giovinetta, Eros Pellini’s very sweet Ragazza lombarda, and Arturo Martini’s far more slender 1935 Frightened Amazons. Concluding the mythological and classical experiments is included a focus on bathers from Rubens to De Chirico, thus moving from what Renoir looks at to what he unwittingly teaches posterity. Flesh bends, and gains a physical plasticity capable of welding light and form in the textural color of Pieter Paul Rubens’ 1622 nymphs crowning the goddess of abundance, as well as the bathers portrayed by the now former Impressionist. Renoir thus tries to imitate the Flemish painter’s nymphs in the pose and plasticity of the figure in his Woman Drying herself of 1912-1914, weaving a coherent dialogue between the two. Dialogue completed by De Chirico’s sensual and nostalgic Ariadne at Naxos of 1932 and Ferruccio Ferrazzi’s Fragmento di composizione.

We then come to the large “landscapes” section where exterior views are alternated with photographs of the artist’s life. It is here that Bolpagni has decided to introduce an emaciated Renoir, now almost overcome by arthritis, which we already see coming into the room with the bronze sculptures. The selected works cover a time span from 1892 with La Seine à Argenteuil to 1913, and we are catapulted mostly to the south of France. More than any other place, Renoir fell madly in love with the light of the Midi and especially with an old village not too far from Nice, Cagnes-sur-Mer, so much so that he finally amazed himself there in the late 1890s by then old and ill. Despite arthritis and missing his wife, now deceased, the artist would not stop working and had a studio built in the garden to continue painting outdoors until his last breath. Photographs, arranged in a long vitrine in the center of the room, depict him as a weary old man in love with art to such an extent that he had his brush tied to his hands in order to still be able to create. Here, too, Renoir’s works are firmly linked to those of Italian artists of the next generation such as Enrico Palucci, with his 1946 Veduta del lago d’Iseo (View of Lake Iseo ), Arturo Tosi, but above all a naturalistic Carrà of the 1930s where the solidity of images and the vibration of colors coexist sadly.

Then we pass the small but full-bodied still life room, among which stand out for their beauty and intensity of colors the Roses in a Vase from 1900 by the protagonist of the retrospective, but also the elusive and lively Dalie from 1932 by De Pisis. Extremely interesting here is the comparison of the various results achieved from the beginning to the end of the 20th century by different artists, French and Italian, of an apparently simple and reiterable subject such as still life. And the Ferrara-born De Pisis, active in Paris in the early 1930s, “matured a pictorial shorthand” born out of his study of Impressionism and post-Impressionism, mixing colors in a crisp and nervous manner creating unique suggestions. Renoir, with his still lifes, succeeds in incorporating pure light into his paintings, and of particular mastery turns out a small work with two “vases boules” vases made by the now elderly artist who defined painting as a restful activity for the brain and says that when he painted flowers he allowed himself to make mistakes and experiment boldly with color, without worrying too much about wasting a canvas. He thus drew the greatest lessons by making mistakes, experimenting and innovating thanks to the flowers he loved so much that, it is said, it would be “flowers” that would be his last word before he died.

But the tour does not end in the same way for the visitor, who will find himself continuing the journey through two rooms that best summarize and characterize the artist’s work: “the female portrait” and “Gabrielle and the world of family affection.” The former is perhaps the most daring and complex section of the entire retrospective, which, by emphasizing the female figures so beloved by the artist, creates a juxtaposition, anything but jarring, advanced by Carlo Ludovico Ragghianti ’s intuition with a Magdalene, from 1540-1560 by Romanino, with its free and tearing femininity. According to the art historian, in fact, that very particular femininity heedless of “venustade et proportione” is the sign of a kind of “pre-incarnation of Renoir,” although it must be remembered how this is not a precise reference, but rather a beautiful suggestion. The imperturbable impenetrability of Renoir’s portraits, on the other hand, seems to find its counterpart, in a chronologically opposite sense, in the works of Antoinette Raphaël Mafai, who fuses the plastic sensuality of Rodin with the primitivism of Jacob Epstein. Renoir, in his female portraits, does not seek a psychology of the character, but rather captures elements of pure nature, escaping the ephemeral and trying to achieve the eternal.

On a different floor, the exhibition continues to discover Gabrielle and the elder artist’s family affections. Here stands a very small sanguine portrait of the young woman that the curator calls a “flower among flowers” , nothing more than a study, but one of palpable sweetness and extraordinary grace in which softness and linearity are perfectly balanced.

The sweetness of the affections finds its Italian counterpart in Armando Spadini, whom in 1919 Giorgio de Chirico is said to have described as a “Renoir of Italy [...] in full possession of all his means of expression; an excellent draughtsman, a colorist full of passion, with a subtle parable of melancholic lyricism.” And it is precisely from here that Paolo Bolpagni creates an exhibition within the exhibition, bringing together many of the Italian’s sweetest works and exhibiting, above all, President Luigi Einaudi’s favorite painting, as well as the back of the 1,000 lire bill “children studying” from 1918.

Concluding the exhibition is “Renoir engraver and lithographer” preceded by a video of a field trip by the artist. Initially the painter did not show a great passion for the art of engraving because of the disconcerting lack for him of the colors to which he was so accustomed, but it would be the volume La lithographie originale en couleurs by André Mellerio, published in 1898, that would prompt him to try his hand at this new technique. After his first unsuccessful experiments and after practice in both etchings and lithography, Renoir chose to adopt a “clear line” of outlines only, which in Henri Loys Delteil’s judgment resulted in an “innate grace, an innocence and freshness that belong to him alone.” And as much as his posterity took lessons, striving to understand his lesson and make it their own, Renoir proves to be, thanks also to this retrospective, a rare flower in perpetual search of an eternal that he managed, with his art, to touch.

Walking through the rooms, one does not sense the difficulty, surely encountered by the curator, in finding parallels between what Renoir saw and was inspired by and those whom, on the other hand, Renoir influenced with quiet delicacy. Nothing is jarringly at odds, not even the swaggering choice to place a screaming Magdalene by Romanino among the Frenchman’s inexpressive beauties. Walking through the corridors, every choice made seems simple, and that is also why Palazzo Roverella turns out to be, once again, after the 2022 Kandinsky exhibition, a buzzing cultural hub of endless possibilities.

Summing up, the one on Renoir and the New Classicism turns out to be a grand and unique exhibition that returns the profile of a restless and calm artist, stubborn and at the same time capable of updating and changing ideas. An artist who managed to break away from the transitory and extremely fragile atmospheres of Impressionism to seek and finally find something solid and eternal, becoming a model for many artists after him.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.