Not much has been heard about the many initiatives organized for the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of Galileo Chini’s birth, and it is not difficult to understand the reasons why: these are mainly situations linked to the cities most marked by his art, there have been no exhibitions of enormous scope, and the artist’s name itself, despite the growing attention of critics to him, which follows an interest that has matured in the last twentyyears after a long period in which Chini remained on the sidelines (he was considered a minor artist, little more than an imitator of the Viennese Secessionists), is not among those capable of moving the masses. Yet on this anniversary there is much out there to learn about Chini’s art, especially on the ground, especially in Tuscany, in the places that were most receptive to his language. To give an idea, in Montecatini an association of tour guides has come up with a two-hour walk among the places of Galileo Chini: the Terme Tamerici, the Terme Tettuccio, the Palazzo Comunale, the Grand Hotel La Pace. And then, the Palazzo Comunale, in the rooms where the “MO.C.A.” (“Montecatini Contemporary Art,” the city’s civic gallery) space has been set up, dedicates an exhibition to him, which began in July and runs until Jan. 7, gathering a good number of his works, selected by Paolo Bellucci, art historian, connoisseur of the artist, and curator of the Galileo Chini repertory.

As the title suggests(Galileo Chini - Works in the Public and Private Collections of Montecatini Terme), it is an exhibition closely linked to the place that hosts it. However, the selection, about fifty works in all, manages to accurately convey the relevance of Galileo Chini in the Italian and international context of his time. The Italy of the Belle Époque is reflected in the works of Galileo Chini. This is an almost unique case in Europe: probably no other artist succeeded, like the Florentine, in becoming an interpreter, and even in the space of a narrow turn of years, of the tastes, expectations and moods of that era. A society that was beginning to discover wealth, tourism, vacations, the superfluous. And Chini was the perfect artist for that society: because he was the most versatile (he could alternately wear the clothes of the painter, the ceramist, the decorator, the set designer), because he was always present at the great international exhibitions and knew how to intercept fashions before anyone else (and was even able to reinterpret them according to his own, highly original sensibility), because every time he exhibited he received acclaim. He was the favorite artist of upper-class Italy in the early 20th century. He was surprising, wrote Filippo Bacci di Capaci, for his “incessant search for sources of inspiration (from the ancient to the traditional, from contemporary aesthetic research to the cultural and linguistic heritages of other ethnic groups, to the most varied handicrafts),” for his “readiness to learn and consequential inventive flair,” for his “naturalness in moving tirelessly from one city to another, when travel was not as easy and quick as it is today.”

Arrangements of

Arrangements of Set-ups of the

Set-ups of the Set-ups of the exhibition Galileo

Set-ups of the exhibition Galileo Set-ups of the exhibition Galileo Chini

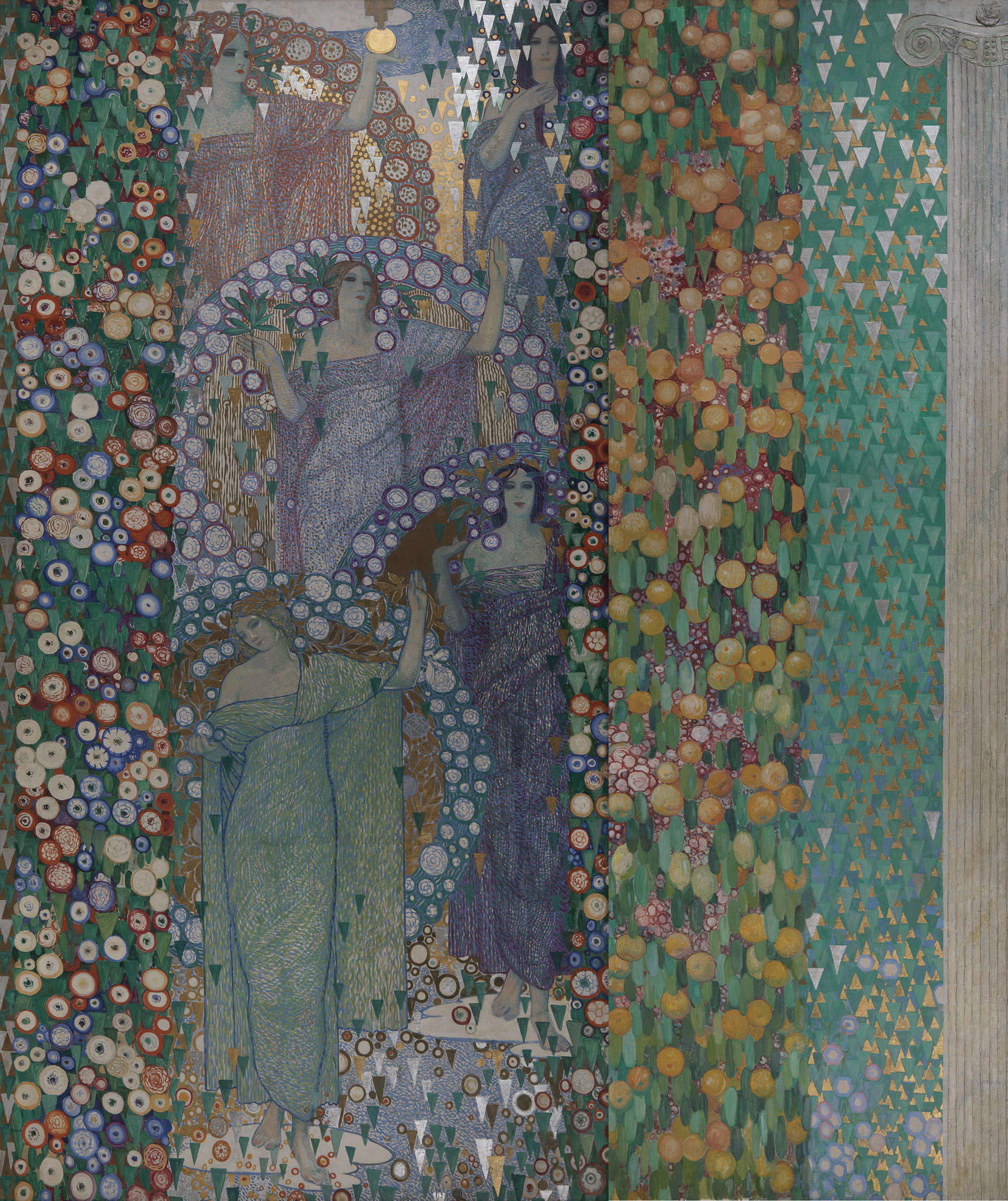

Set-ups of the exhibition Galileo ChiniThe exhibition in Montecatini Terme succeeds, with clarity and lightness, in bringing out the varied and multifaceted character of Galileo Chini’s art. It is a review with a rather usual layout, similar to that of several exhibitions that in recent years have been dedicated to the versatile Tuscan artist: no great novelties are to be expected from the exhibition, especially if one is already familiar with Chini’s production (on the other hand, those who have never seen an exhibition on Chini, go without delay). A classic thematic itinerary with the room dedicated to decorative painting, the one on his stay in Thailand, the section on landscapes (and in particular on the landscapes of his beloved Versilia), the lunge on graphics, and so on. However, the exhibition at the Palazzo Comunale in Montecatini deserves attention, for at least three good reasons (beyond, of course, the strong bond between the artist and the city, where Chini first went in 1904). The first is encountered immediately at the start of the itinerary: it is the sumptuous Classical Spring, a large canvas four meters high by more than three meters wide, which the artist painted in 1914 for the room of the Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović at the Venice Biennale that year, part of a cycle of fourteen panels, some of which were originally paired, all dedicated to spring. It is a painting in which the most colorful season takes on the guise of five female figures striding, almost in dance step, over a meadow of ringing, sparkling flowers, closed on the right by the outline of a column with the mask of the god Hypnos: the references, of course, are to Klimt, Jugendstil and European symbolism, which Chini reinterprets by filtering suggestions from northern Europe through the warmth of Tuscany, the air of Venice, the vitalism of Italian literature of the time, but also through the simplicity and tendency toward abstraction of Eastern art that he encountered firsthand during his stay in Siam. Chini himself had written that, in painting this cornerstone of his production, he had been thinking of “the springtime that gladdens this sweet Venice when it welcomes artists from all over the world, of art, a spiritual springtime that eternally reemerges,” and that he wished to avoid “arduous and abstruse subjects” in order to concentrate only on “ranges and forms of color and composed pleasing tones.” The Classical Spring, a radiant but also solemn and mystical painting (the mask of the god of sleep harks back to the theosophical thought that fascinated large groups of artists in the early 20th century), now owned by of Fondazione ViVal Banca, was moreover also present at the exhibition on Galileo Chini that was set up at the end of 2021 in the rooms of Villa Bardini in Florence, where it was at the center of a section devoted to the contribution that Chini guaranteed to the Venice Biennials: in Montecatini, on the other hand, it is the centerpiece, in the central hall of the Palazzo Comunale, also with early 20th-century ornaments, of the section devoted to decoration. In the catalog we read that at the 2014 Biennale, when the panels were exhibited, there were “no eyes other than for the paintings of the Florentine artist, who unexpectedly became the protagonists of the entire event.” Perhaps the enthusiasm of the Montecatini exhibition is too high, but it is true that there were many positive comments about his panels, and the fact that after the exhibition they were sold is further evidence of their success, since they were born as ephemeral vestments: the Classical Spring, which remained in the possession of the artist’s family, was later destined by the latter to the Montecatini Art Academy, whose collection, in 2011, became the property of the Valdinievole Credit Bank Foundation.

The second reason is the section devoted to Florence after the destruction of World War II, a tragic subject that is often not even touched upon in exhibitions on Chini, partly because there are not many works that the artist devoted to this theme: despite Chini’s adherence to Fascism, shortly before the enactment of the racial laws he began to develop an ever-growing sense of disillusionment, which later erupted into open criticism with a courageous painting, known today as The Mad Dictator (as well as The Sad Madman), which the artist imagined in May 1938, on the occasion of Adolf Hitler’s visit to Florence. The painting (currently at the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Bologna, while the preparatory sketch is at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Florence: it was purchased by the Uffizi Galleries in 2019) would take shape only the following year, when Germany invaded Poland and Chini wanted to denounce with his painting the madness of war, but in the meantime the artist had had his professorship at the Academy of Fine Arts revoked and his PNF membership withdrawn precisely because of his dissenting positions: a manifesto against the madness and horrors of war, it was exhibited for the first time in 2019. The Montecatini exhibition tells this story and, moreover, launches the proposal to change the painting’s name, titling it The Seer, since the madman takes the form of a Laocoon, already caught in the coils of the fatal serpent, who wanders unheeded while behind him we witness a scene of devastation, bodies of dead men and women lie, the landscape is devastated: it is one of the most brutal paintings of those years.

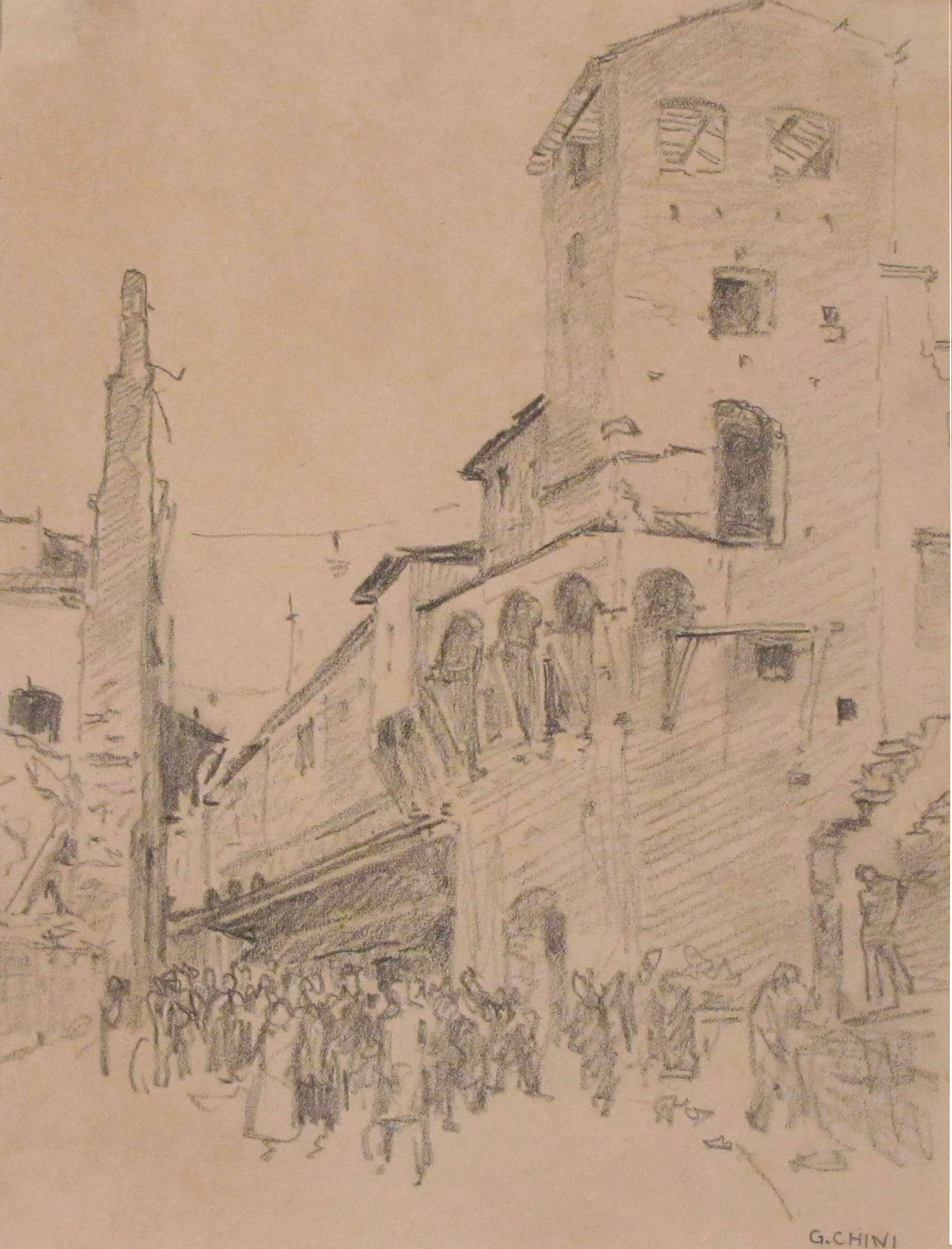

While The Mad Dictator is only evoked, as the work is not in the exhibition, it is nevertheless possible to observe some works that testify to the conditions in Florence after the bombings of 1943. Chini’s family directly suffered the consequences of the war, since in 1943 they were forced to evacuate to Montale, a town between Prato and Pistoia, and the artist’s personal drama is reflected in the paintings and drawings depicting the destruction of Florence’s historic center. The artist was able to return to the city after its liberation in September 1944: a city in rubble opened up before his eyes. Chini, at that time a man of seventy-one, “felt the need and moral obligation,” the exhibition catalog reads, “to travel daily to the places of destruction of his beloved Florence to bear witness with his painting to the horrors of the war and its consequences.” We are left today with about 20 paintings, almost all of which were later donated to the City of Florence, that preserve memories of how Florence was reduced: the landscape cut, the somber and earthy tones of Chini’s paintings, the choice to include even small groups of inhabitants wandering among the ruins of the city give us not only a sadly vivid image of the conditions in the center of Florence when the war was over, but also allow us to enter thepainter’s soul, to understand his pain, almost to suffer along with him as we see how the war ended up crashing down with all its violence on his city, the city he had always loved, one of the most beautiful cities in the world. This is a Galileo Chini that one does not often get to see in exhibitions dedicated to him.

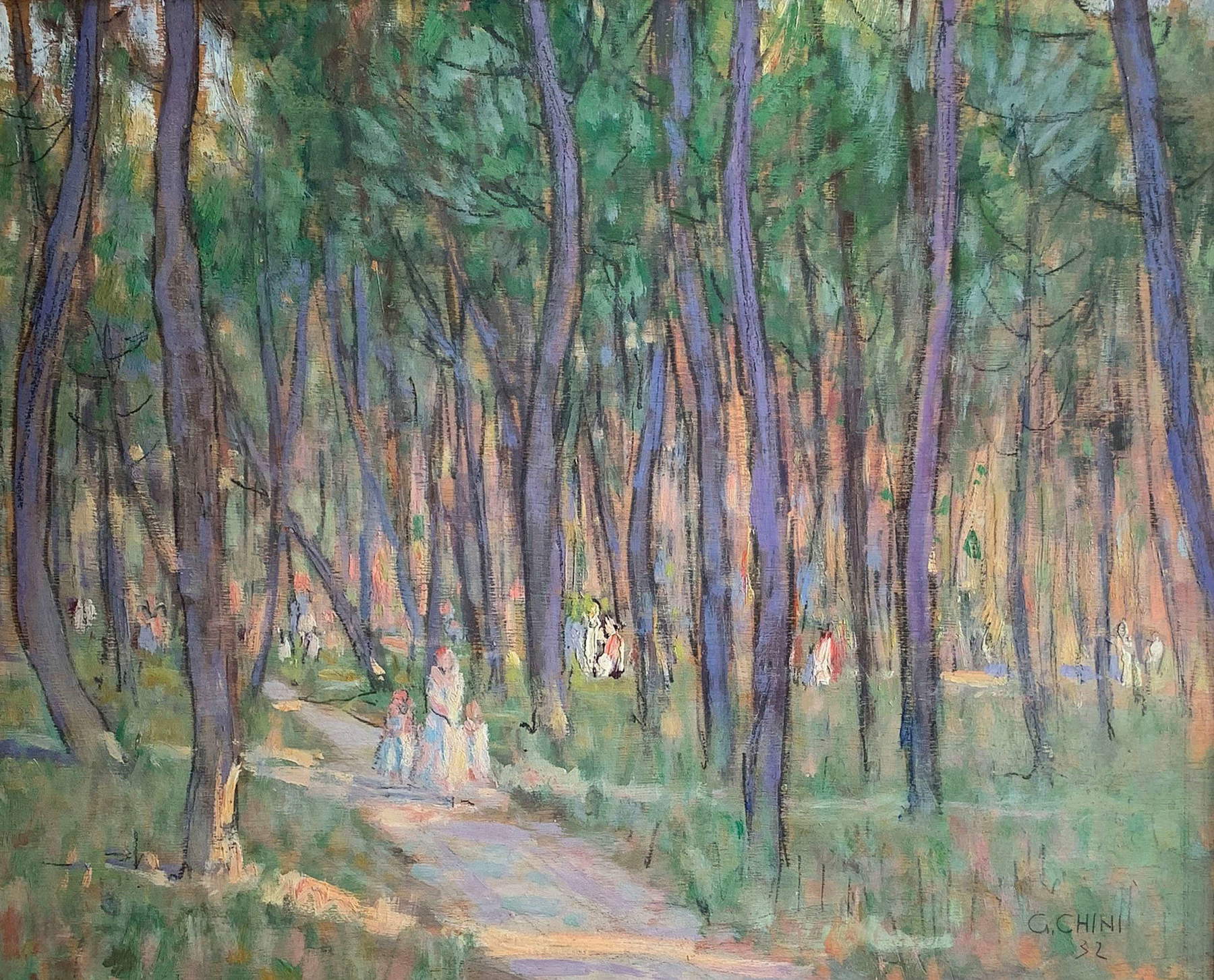

Finally, the third reason for interest is the room devoted to the last Galileo Chini, to the part of his production that tends to be most neglected, yet coherent, extraordinary and dramatic conclusion to one of the most original events in Italian art of the early part of the twentieth century. After the exertions of the war, Chini is a gloomy artist, burdened by an eye disease that will lead him to blindness, an artist who suffers: his works lose their light, lose their colors, lose the vital freshness of past years and become gloomy, dense, material, closer to the expressionism of a Lorenzo Viani than to the flourishes of Art Nouveau towards which he had always turned his gaze. Then the subjects change: Galileo senses the nearness of the end, and death becomes a recurring theme in his production. A tragic spirit takes possession of him, responsible for the production of works that, Fabio Benzi wrote, “also signify the impossibility of a generation, the decadent one born in the last quarter of the previous century, to adapt to the historical, social and cultural upheaval caused by World War II.” Before his farewell, Chini makes time to paint a bleak final work, The Last Intercourse, which icastically closes the itinerary of the Montecatini exhibition: in this harsh, suffering, scratchy, arid painting with earthy tones, the artist depicts himself, naked, in the arms of death that envelops him with its black mantle and welcomes him against the backdrop of a deserted landscape, with only a bare olive tree as its only presence, although a glimmer of blue in the sky can be glimpsed in the distance, a faint sign of hope. This is the image with which Chini decides to consign himself to history, and this is also the image with which the exhibition closes, tacking on a parallel, in the same room, with Joan Miró’s Woman Wrapped in a Bird’s Flight , one of the Catalan artist’s most significant works preserved in an Italian public collection, since the painting is the property of the Municipality of Montecatini Terme.

Galileo Chini,

Galileo Chini,

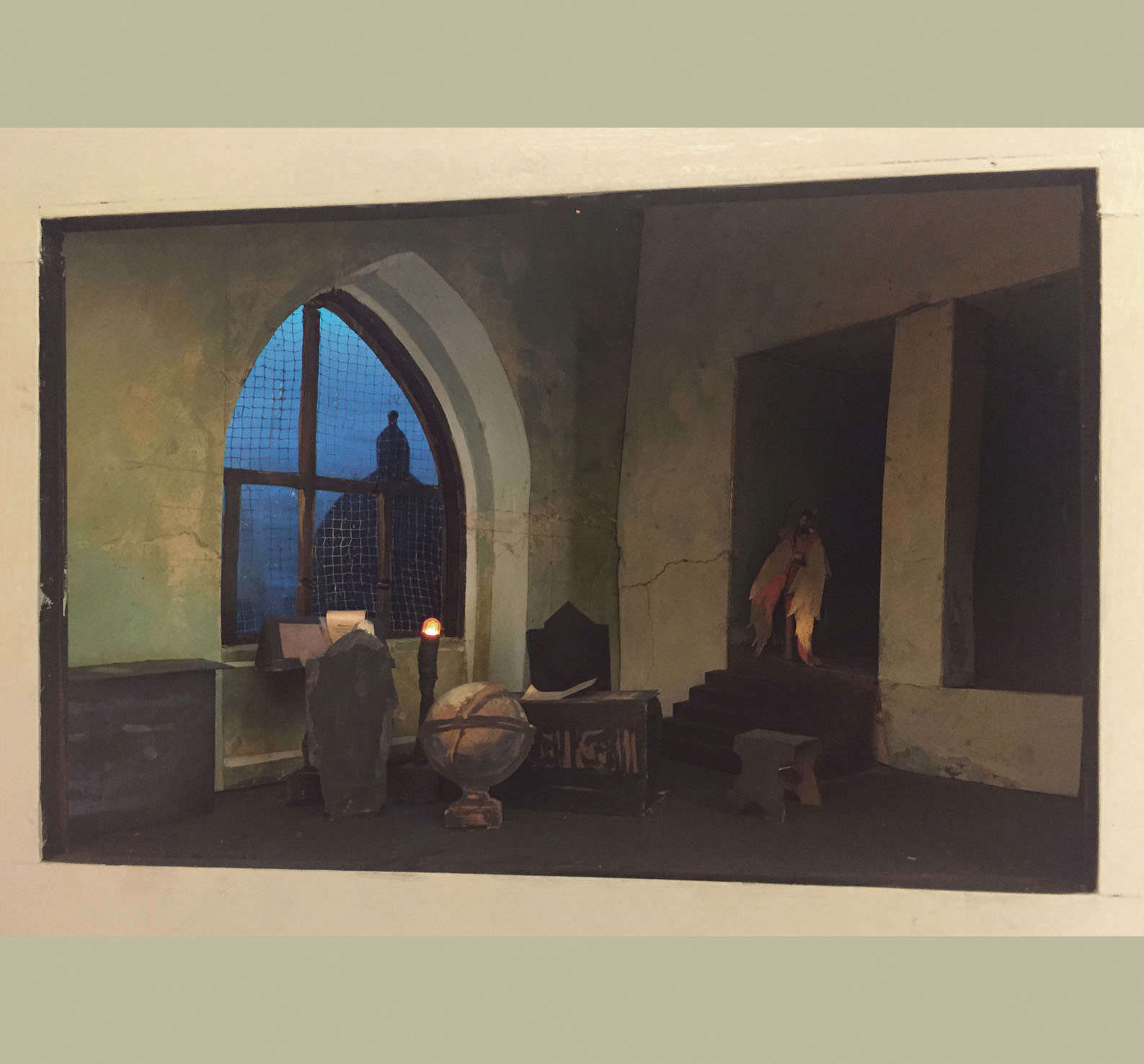

Also deserving of special mention are the small focus on Chini the scenographer, with the exhibition of a three-dimensional model for Faust executed between 1917 and 1935 and then never realized, and the section devoted to landscape painting, a genre to which Galileo Chini devoted himself with great vigor between the 1920s and 1930s, when the commissions for the great decorative undertakings that had kept the artist busy at the beginning of the century were disappearing, and it was therefore necessary to reinvent himself: the artist thus knew how to continue to be the prolific and talented ceramist he had always been, but he also proposed himself as an easel painter who, albeit belatedly, looked to the poetics of the landscape-state of mind to restore on his panels tranquil and soothing views of Tuscany, especially Versilia, a land where he used to spend long stays. Here, then, is a painting like Early Morning Hours captures all the calm of a rosy dawn on the Fossa dell’Abate, the canal that divides Lido di Camaiore from Viareggio, with the pine forests still in shadow and the moon beginning to give way to daylight, while Presso Camaiore stands out for its almost Impressionist verve , with birch trees that seem truly stirred by the wind, and again the Pineta piccola seems almost to refer, with its acid colors and its regular and orderly course, to Klimt’s landscapes.

The stated goal of investigating the relationship between Montecatini and the works of Galileo Chini, the artist who more than any other has marked the spa town, can therefore be said to have been achieved. And operations such as the exhibition in Montecatini Terme, that is, popular reviews of a good level, scientifically valid, designed for the area, supported by a good educational offer, should be encouraged and supported: they have low costs (in this case, the review was set up entirely with works preserved in the city and its surroundings, thus without resorting to loans from outside), excellent spin-offs, they carry out a fundamental cultural action, and they offer valuable opportunities for everyone, inhabitants and visitors, to deepen their knowledge. In addition, Galileo Chini - Works in the Public and Private Collections of Montecatini Terme is also free admission: a generosity that we hope will be amply repaid with the success of the public.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.