Against the simplifications of a scholastic vulgata that often tends to trivialize the events of the fifteenth century in Ferrara, leading one to consider them almost a sort of vernacular emanation of a broader “Renaissance” centered on Tuscany, one could pronounce d’embléand even if only by resorting to the resolute and definitive judgment that Roberto Longhi had carved out in his seminal Officina ferrarese, where he acknowledged that, in the last decade of the 15th century, Ferrara sat “higher than anywhere else in Italy,” and this was due to the merit of Ercole de’ Roberti, an artist who had conquered “a situation so personal that in those times it could find no other comparison of value than in Leonardo.” The Ferrara in which Ercole de’ Roberti moves is a city where radical urban solutions are invented, where capital events of Italian literature of the time are written, it is a hospitable gateway through which cultures from the East enter, it is the center of a Renaissance whose ramifications extend far beyond its walls. Renaissance in Ferrara, then, rather than “Renaissance in Ferrara,” as the exhibition dedicated to Ercole de’ Roberti and Lorenzo Costa, and curated by Vittorio Sgarbi and Michele Danieli, which the renovated halls of the Ala Rossetti and Ala Tisi of the Palazzo dei Diamanti are hosting until next June 19, is titled.

Exactly ninety years have passed since the huge exhibition on art in Ferrara in the Renaissance that provided Longhi with the cue to composeOfficina ferrarese, which was born as a sort of long commentary on the Ferrara Renaissance Exhibition, was organized precisely at the Palazzo dei Diamanti. It was 1933, and an initiative needed to be organized to celebrate in the most fitting way the fourth centenary of Ludovico Ariosto’s death: the will of the people who made that exhibition possible (notably the podestà Renzo Ravenna, the Fascist quadrumvir Italo Balbo, at that time the kingdom’s minister of aeronautics but always tied to his city so much as to consider himself a sort of modern continuator of the Este family, and a close friend of Ravenna’s, and then the curator Nino Barbantini and the then director of the Pinacoteca di Ferrara, Arturo Giglioli) was to avoid a conference of academics, and to imagine, if anything, some event of broader wide-ranging, which should not have “a village character, but rather rise to national interest” (such was the intention of Italo Balbo, who played a decisive role in making the exhibition possible). And indeed, in the face of the flood of rhetorical and triumphalist initiatives that accompanied Ariosto’s anniversary, the Exhibition of the Ferrarese Renaissance has always been recognized as a solidly structured and unquestionably valuable exhibition, as a seminal moment, the crowning achievement of a dense season of studies on the arts in the city between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and as the start of a period of exhibitions designed for a wide audience (curiously enough, the exhibition, which in the end drew more than 79.000 paying visitors, arrived, like this year’s, after a restoration of the Palace and a new organization of the rooms, although those works had been conducted, Andrea Emiliani wrote, in an approximate way): nevertheless, it should not be forgotten, as Marcello Toffanello recently pointed out, that that exhibition was one of the many occasions by which the regime tried to make itself presentable.

The scientific results of that exhibition and its assumptions have been extensively covered in the recent bibliography, but it will be useful to recall, in order to establish some coordinates that can make the reading of the 2023 exhibition easier as well, some elements: first of all, the fact that it had not rained down suddenly, but rested its pillars on the foundations built by Adolfo Venturi who, in the 1980s of the previous century, published some important essays on the arts in the Este territory that, Andrea Emiliani acknowledged, “must be considered the most solid foundation for any adequate reconstruction” (and the comparison with Venturi, who moreover also played a role in the organization of the first ever exhibition on the arts in Ferrara in the fifteenth century, set up in 1894 at Burlington House in London, was also inescapable for the organizers of that review). It was then an exhibition that would probably be unrepeatable today, since more than 250 works (as many as can be found marked in the catalog) convened at the Palazzo dei Diamanti: the occasion was indeed facilitated by a propitious period, opened in 1930 by a muscular display, that is, the enormous exhibition of Italian art in London desired by Mussolini, which opened a decade of great exhibitions devoted to accumulation. And that same accumulation that had characterized the Palazzo dei Diamanti exhibition, which also provided the public and scholars with the first important opportunity to admire so many works of the Renaissance in Ferrara in the same place, left many questions open: it is not, however, an aspect to be read as a defect, since at that time exhibitions, especially of that magnitude, were set up above all to test the material on which one had worked and not to present acquired results. Longhi’sOfficina ferrarese would come to bring order on such matters, which, relying on an even larger number of works than those that the exhibition unfolded in the halls, reduced Venturi’s “pro-Ferrarese” opinion (according to which from Ferrara a language would have radiated that would have invested most of northern Italy), specified the scope of the novelties of Ercole de’ Roberti (not to downplay them, recalls Marcello Toffanello in the catalog of Renaissance in Ferrara, but to update them according to a vision that took into account not only personal derivations, but also the “reconstruction of historical frameworks circumscribed to precise geographical situations”), attributed to Ercole by way of coup de théâthree the September of Palazzo Schifanoia, eliminated the fictitious figure of “Ercole Grandi,” a nonexistent artist who wanted to be constructed from some confused readings of a historical document (the works that were assigned to him were variously distributed), and tried to shed light on Lorenzo Costa’s youthful years, about which the exhibition had remained reticent. The results of Longhi’s work, poorly summarized here, asserted themselves with an authority that has fascinated generations of scholars. And a plaque, included in the renovated itinerary of the Palazzo dei Diamanti, commemorates his Officina ferrarese.

So what are the purposes of a new exhibition ninety years later? Certainly not to propose a re-edition, which would necessarily be out of date, of that exhibition, but, if anything, to do something even more extensive, albeit on several timescales: the first, looking backwards, is given by the exhibition Cosmè Tura and Francesco del Cossa, held at Palazzo dei Diamanti in 2007 and curated by Mauro Natale, while the second is the present exhibition, and others will follow, always with pairings (Mazzolino and Ortolano, Dosso and Garofalo, Girolamo da Carpi and Bastianino). The result, therefore, will be the most extensive survey of the arts in Ferrara between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries that has ever been attempted, all in the light of the last decades of research, to offer new framings, to revisit artists sometimes overlooked in the past (it is the case, as will be seen, of Antonio da Crevalcore, who is given a prominent place in the exhibition on Hercules and Lorenzo Costa), to return to questions that have remained unresolved (such as the attribution of the Settembre di Palazzo Schifanoia, to which it will be convenient to return with a separate article). And, of course, in the case of the exhibition that opened last February 18, not so much to offer the public readings that will revolutionize our understanding of Ercole de’ Roberti and Lorenzo Costa but, for example, to “isolate the main ingredients of the language” of the former, as Michele Danieli writes in the catalog, a language “which in turn will constitute the basis for the development of Lorenzo Costa’s,” or to reiterate the modernity of the latter’s language, an artist who during the twentieth century was perhaps little considered because of what was considered a sort of defect (as the curator mentioned during the presentation of the exhibition), namely the “eclecticism” that allowed him to look to Ferrara, Venice and central Italy to fuse everything together. One will discover, therefore, an extremely curious, receptive, modern and original Lorenzo Costa. It should also be remembered that the exhibition that opened a few days ago at the Palazzo dei Diamanti turns out to be the largest monographic exhibition ever on Ercole de’ Roberti to date, and since it is not a simple operation to gather the works of the Ferrara artist, scattered in museums and collections halfway around the world, the difficulty of the operation should be considered, and the fact that for a reasonably long time it will be difficult to see anything even similar again.

The tour itinerary begins in a room that arranges in brief succession the works of all the most important artists who were active in Ferrara at the time when the career of the young Ercole de’ Roberti began: we begin, then, at Palazzo Schifanoia, and to evoke that enterprise (of course, for those going to see the exhibition, a visit to the Salone dei Mesi will be a must) come theAscension of Christ by that curious and enigmatic artist who is the Master with Wide Eyes, perhaps a pupil of Cosmè Tura (the great Ferrara artist is featured with the Madonna of the Zodiac from the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice) and a Madonna and Child by Gherardo da Vicenza, a work at the center of intense attributional debates. As anticipated, it was Longhi who surprisingly assigned Ercole de’ Roberti’s Settembre di Schifanoia, which would thus come to be seen as the artist’s earliest work: not being able to see it in the exhibition, we content ourselves with a reproduction of it on a reduced scale, and continue our journey with the second room, in which some of the cardinal points that nourished Ferrara’s artistic events are affirmed: the gaze cannot but be turned first of all to Padua, so that a cornerstone of Andrea Mantegna’s painting, the St. Euphemia on loan from the National Museum of Capodimonte (the great Venetian artist was, moreover, in Ferrara in 1449), as well as a much-discussed St. Peter the Martyr in wood, which, if it is to be attributed to Donatello, is to be referred to the early part of his stay in Padua (thus around 1443 or shortly after), while the large bronze group, arriving from Ferrara Cathedral, with Christ Crucified between the Madonna and St. John, a challenging work by Niccolò Baroncelli and Domenico di Paris that offers one of the surely most scenic passages in the exhibition, falls within the scope of Donatello’s language. The Venetian front, on the other hand, is represented by another debated work, the Head of St. John from the Pesaro Museums (according to some by Giovanni Bellini, while according to others, including Sgarbi, by Marco Zoppo: in the exhibition it figures as a work by Bellini but the attributive debate is not silenced), as well as Marco Zoppo’s St. John the Baptist. In between, there is the singular Annunciata from a private collection for which no name has yet been found, and which Longhi wanted to be the work of a Ferrarese who looked to Padua (the exhibition instead tries to solve the problem by likening it to the production of Gentile Bellini, even though it is the work of an artist evidently imbued with Paduan culture), while in dialogue with the group of Baroncelli and Domenico di Paris, Vicino da Ferrara’s Crucifixion arrives from Paris to invite the public to delve into the Ferrara the work of this practically anonymous artist (the name “Vicino da Ferrara” is an invention of Longhi, who used it to indicate a painter close, precisely, to Ercole de’ Roberti) belongs to the first season of the Renaissance in Ferrara, that of Cosmè Tura and Francesco del Cossa, and it is a work that adds a compositional rigor mindful of Piero della Francesca’s solutions to a monumentality that is still Paduan and an expressiveness and restlessness that are instead typical of the Ferrara painters. Flemish works are missing to complete the picture of the experiences that were the basis of what would later develop in Ferrara after the mid-15th century, and similarly absent are works by Piero della Francesca, who was another artist of paramount importance (he, too, was in Ferrara in 1449, to work on the Castello Estense), but the catalog and room apparatuses are exhaustive in providing the public with the complete picture.

Thus we return to Ercole de’ Roberti’s beginnings, and back to Schifanoia: in the summer of 1470, Francesco del Cossa wrote to Duke Borso d’Este essentially to ask to be paid more. The duke’s reply is not preserved, but the fact that immediately thereafter the artist is attested in Bologna leaves no doubt as to the tenor of the reply. If we imagine an Ercole de’ Roberti active in the Schifanoia worksite, it is safe to assume that the painter followed his older colleague: in fact, he worked together with him on the Griffoni Polyptych, as part of what Carlo Volpe described as the “most formidable and productive association known to the history of art.” In fact, Cossa did not force the very young collaborator, then barely twenty years old, into the role of executor, but left him very wide margins of freedom, and Ercole responded by returning one of the highest pages of the entire Renaissance, the astonishing predella in which he poured all his incomparable inspiration, showing himself to be an imaginative artist, endowed with excellent narrative skills, an extraordinary film director who in his world just twenty-seven centimeters high organizes a colorful and frenetic universe, with the flair of an engineer and with supreme imaginative flair. Of the Griffoni Polyptych, which an interesting exhibition held in Bologna’s Palazzo Fava during the first wave of Covid reconstructed for the first time in its entirety by bringing together the pieces scattered all over the world, the exhibition displays, in addition to the predella, the roundels with the archangel Gabriel and with the Virgin and the side pillars with the saints, all the work of Hercules, while the parts that are due to Cossa have remained at their locations.

In the next room, however, we delve into another occasion when Francesco del Cossa and Ercole de’ Roberti worked together, though not on the same terms as in the Polyptych: in 1474, Cossa had in fact begun to paint the frescoes in the Garganelli chapel in St. Peter’s in Bologna, and when he died at just over 40 in 1478 he was succeeded by his younger collaborator, who completed the work. The chapel was destroyed between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (we know part of the scenes from copies), and the only fragment that survives is Hercules’s Weeping Magdalene, already featured in the recent exhibition on the Felsine Renaissance at the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna and a work that, Giuseppe Adani has rightly written in these pages, “soars us in plenitude over theentire universe of the sacred and lost poem of Hercules,” a poem whose expressive force, celebrated by the sources (including Michelangelo), is nonetheless all handed down by the powerful lacerto, which in the exhibition dialogues in exemplary fashion with a Madonna dolente by Guido Mazzoni and a Busto di san Domenico di Guzmán by Niccolò dell’Arca, counterparts along the Via Emilia of the power of the young Ferrara, evidence of how the arts in Ferrara were nourished by suggestions from the rest of the region and, conversely, how Ferrara in turn exported its innovations elsewhere (the examples of the Piedmontese Giovanni Martino Spanzotti, present with the Madonna Tucker in the Palazzo Madama in Turin close to the Bolognese Cossa, and of the Emilian Giovanni Antonio Bazzi, an artist with the same name as the more famous Vercelli-Senese Sodoma, dusted off on the occasion of this exhibition to attest to his dependencies on the Cossa of the Pala dei Mercanti). Wedged here, again in the wake of Francesco del Cossa’s painting, is the story of Antonio Leonelli da Crevalcore: the three monumental canvases with St. Paul, the Madonna and Child with an Angel and St. Peter alone occupy an entire wall, while not far away one can admire his Holy Family with St. John the Baptist. Works that interpret with accents of nervous originality (look at the draperies of the saints) and with a stern air, again, the Cossa of the Merchants, placing Antonio da Crevalcore among the most interesting artists of that turn of the century (we are in the ninth decade of the fifteenth century).

Antonio Leonelli called Antonio da

Antonio Leonelli called Antonio da Antonio

AntonioWe then return to follow, in strict chronological order, the affairs of Ercole de’ Roberti: his stay in Bologna is attested by the marvelous diptych depicting the de facto lords of Bologna, namely Giovanni II Bentivoglio and his wife Ginevra Sforza, one of the highlights of the exhibition, arriving from Washington. This is, according to Longhi, the “most beautiful diptych portrait in all of 15th-century Italy” after Piero della Francesca’s double portrait of the Montefeltro dukes, with whom the relationship is obvious and undeniable (moreover, interestingly, Battista and Ginevra Sforza were sisters): in the exhibition, the diptych weaves a fruitful dialogue with a Portrait of a Young Man by Antonio da Crevalcore, which we must imagine was also anciently paired with a female portrait in a nuptial diptych, and with the Portrait of a Man from the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum in Rotterdam, dense with Antonellesque reminiscences, and still at the center of an attributional question that divides it between Ercole de’ Roberti and Lorenzo Costa. A first invitation, then, to the second part of this double monograph, but not before finishing the journey among the works of Hercules. And the Hercules of the 1570s and 1580s is an artist who scrupulously observes all that goes on around him, who blends with resolute determination, supreme skill and witty ingenuity the composure of Piero della Francesca, the minuteness of the Flemish, the arch lines of German art, as well as distended Venetian openings. It is a pity that the exhibition does not feature the Portuense Altarpiece, the only work by Hercules that can be dated with certainty, and the only altarpiece that remains of him, since the other one known to us, the St. Lazarus Altarpiece, was destroyed in Berlin during World War II: the absence of this fundamental masterpiece is not, however, a demerit of the organizers of the exhibition, since the work, preserved at the Pinacoteca di Brera, is among the thirteen works that the Milanese museum generally excludes from loan because they are strong of “great notoriety with the public, including the international public,” and are considered to have identity. For the sake of completeness, however, it should be noted that this list, since it was first made known, has been modified on only one occasion, namely sometime between May and August 2021 according to the museum’s website historian, precisely in order to add, to the list thatfrom the outset has counted twelve odd works such as Mantegna’s Dead Christ, Piero della Francesca’s Montefeltro Altarpiece, Raphael’s The Marriage of the Virgin, Caravaggio’s Supper at Emmaus, and Hayez’s The Kiss, precisely the Portuense Altarpiece: it is, moreover, the only modification the list has ever undergone. Had it been in the exhibition, it would have been the most impressive work in the show, with dimensions a few centimeters larger than those of Vicino da Ferrara’s Crucifixion.

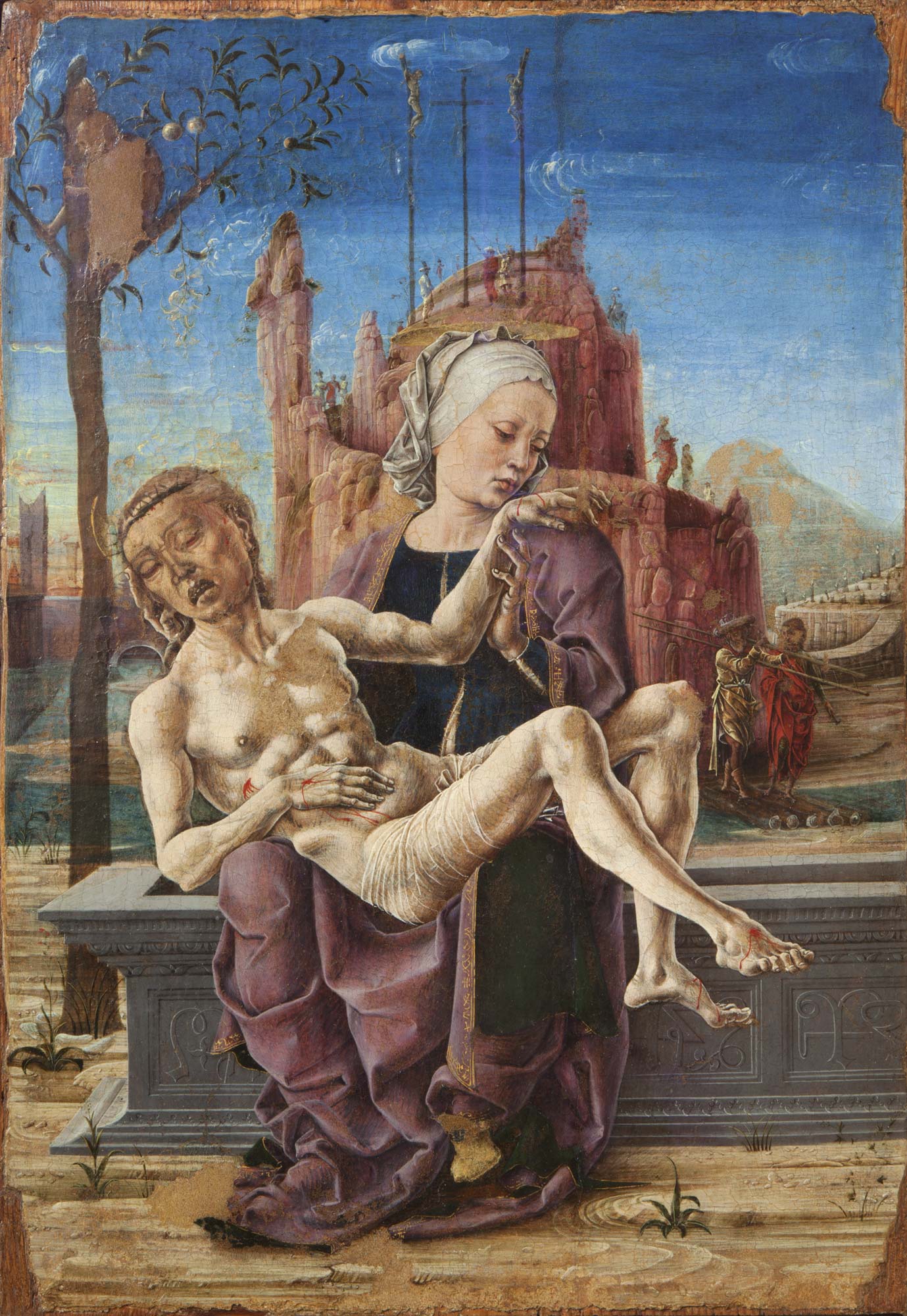

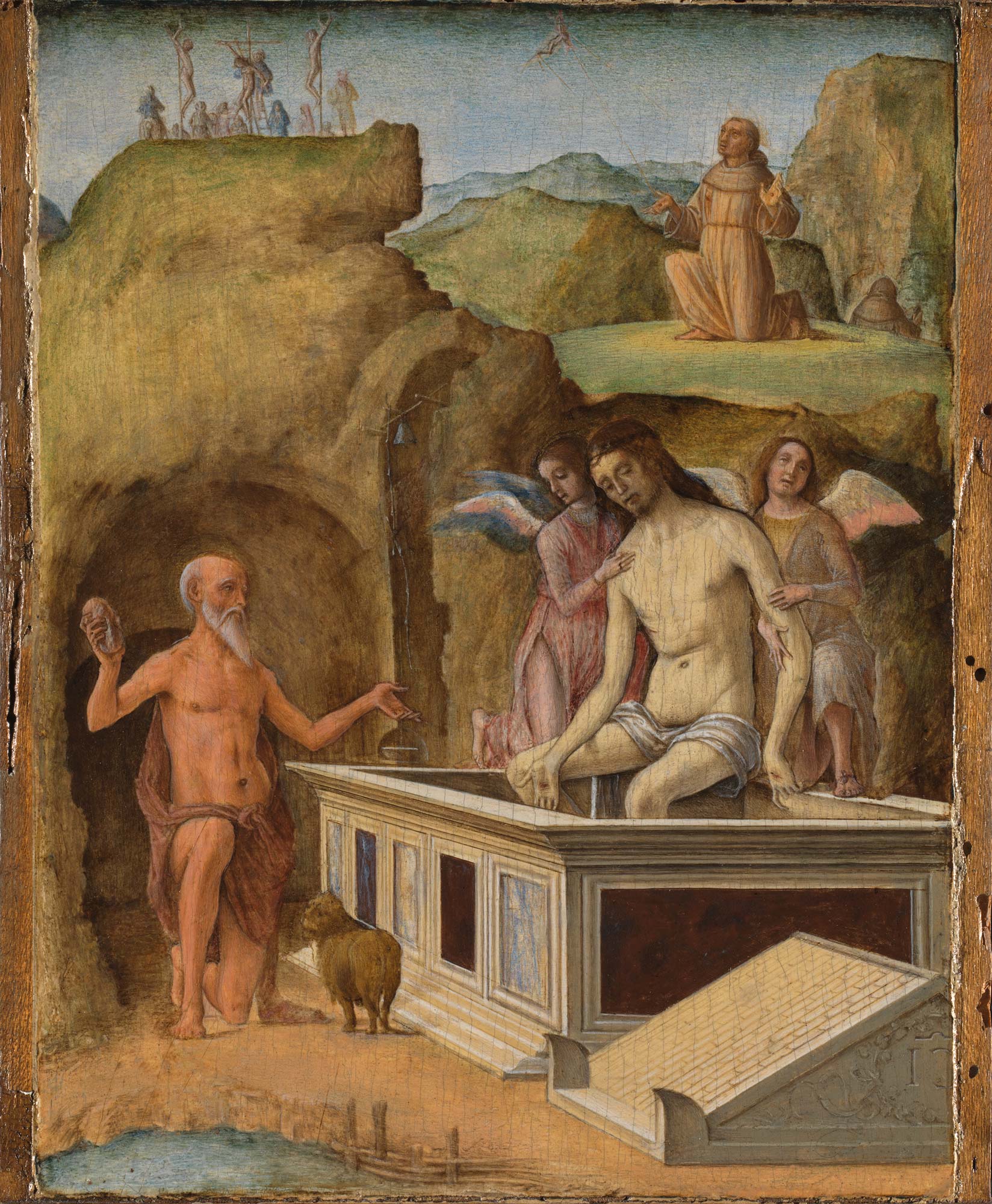

We are consoled by a comparison of a very high-fidelity reproduction of the Liverpool Pietà (the original remained in England because it was too fragile), part of the predella in San Giovanni in Monte (we do not know, however, whether an altarpiece ever existed in the Bolognese church), and compared with the famous Pietà by Cosmè Tura in the Museo Correr in Venice to emphasize its relationships, as well as with a stone Vesperbild by a Bohemian sculptor to recall its iconographic origins, and with another Pietà, by Mazzolino, which looks straight at the Pietà by Ercole de’ Roberti. Berlin’s Saint John the Baptist is evoked by a harsh drawing of a foot, and the part of the exhibition on early Hercules closes with a splendid pairing of works from the mid-1980s, the Saint Michael from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna and the delightful Madonna and Child between two vases of roses, from the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Ferrara. For the San Michele, the exhibition is an opportunity to reaffirm the Barbertian autography: “who else,” wonders Michele Danieli, “could have concentrated such expressive force and such confidence in the articulation of volumes in such a small surface?” Decidedly less contested, however, is the Madonna that was first attributed to Hercules by Adolfo Venturi, and has never since been questioned. We then come to the room that deals with the last Ercole, considering a span from 1486, the year in which he became court painter at the Este family (a position that, according to the sources, procured him a great deal of work: unfortunately, however, very little remains to us today, and for the most part these are works executed for private devotion, and yet a considerable portion of that very little is on display), until 1496, the year of his death. This phase of Ercole’s career is represented in the exhibition with several cornerstones, starting with an exceptional loan, that of the diptych from the National Gallery in London, the only work that remains to us of those that Ercole executed for Eleonora d’Aragona, duchess of Ferrara, wife of Ercole I d’Este. The first panel depicts theAdoration of the Shepherds while the other puts together, in a scene of astonishing compositional direction, the Deposition from the Cross, the Vision of St. Jerome and the Stigmata of St. Francis: “masterpieces of spatial organization,” Danieli writes, “the small panels show a clear, softened painting, sensitive to the innovations of the Po Valley.” Here, then, is the mark of the last Hercules, to be further discerned in the beautiful Madonna and Child in the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, which, in its terse Venetian light preserves the ancient monumentality, in the two panels devoted to the women of antiquity (the Portia and Brutus arriving from the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, and the Lucretia from the Galleria Estense in Modena, given to Hercules along with Giovanni Francesco Maineri), exceptionally reunited, and formerly part of a single decorative cycle commissioned by the Este, and especially in the calm Institution of the Eucharist, also arriving from London, a work that gives an account of a Hercules grappling with a modern rethinking of his syntax: his life comes to an end that he was only forty years old, or perhaps a little older, and we will never know in what direction he would move by the turn of the century.

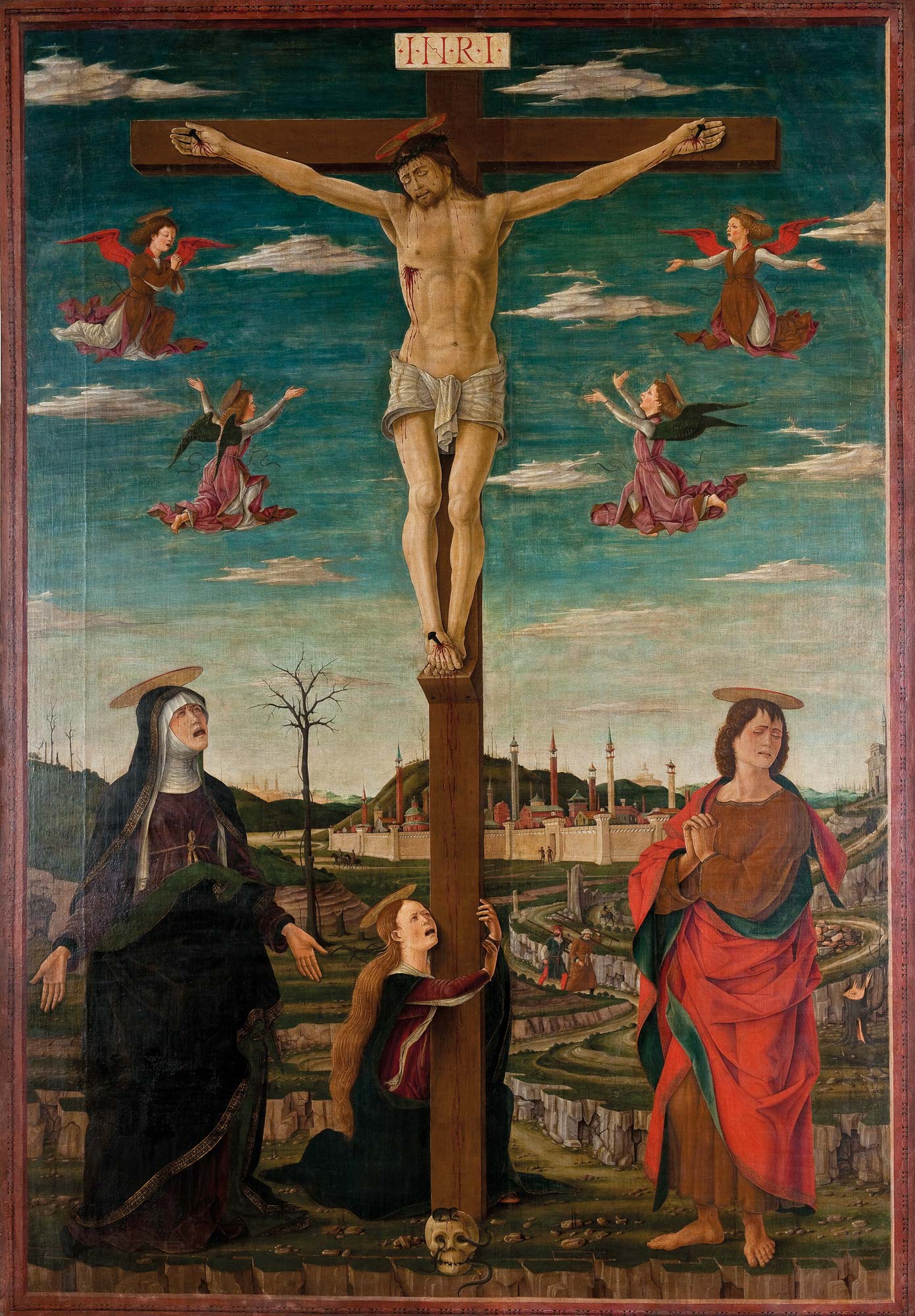

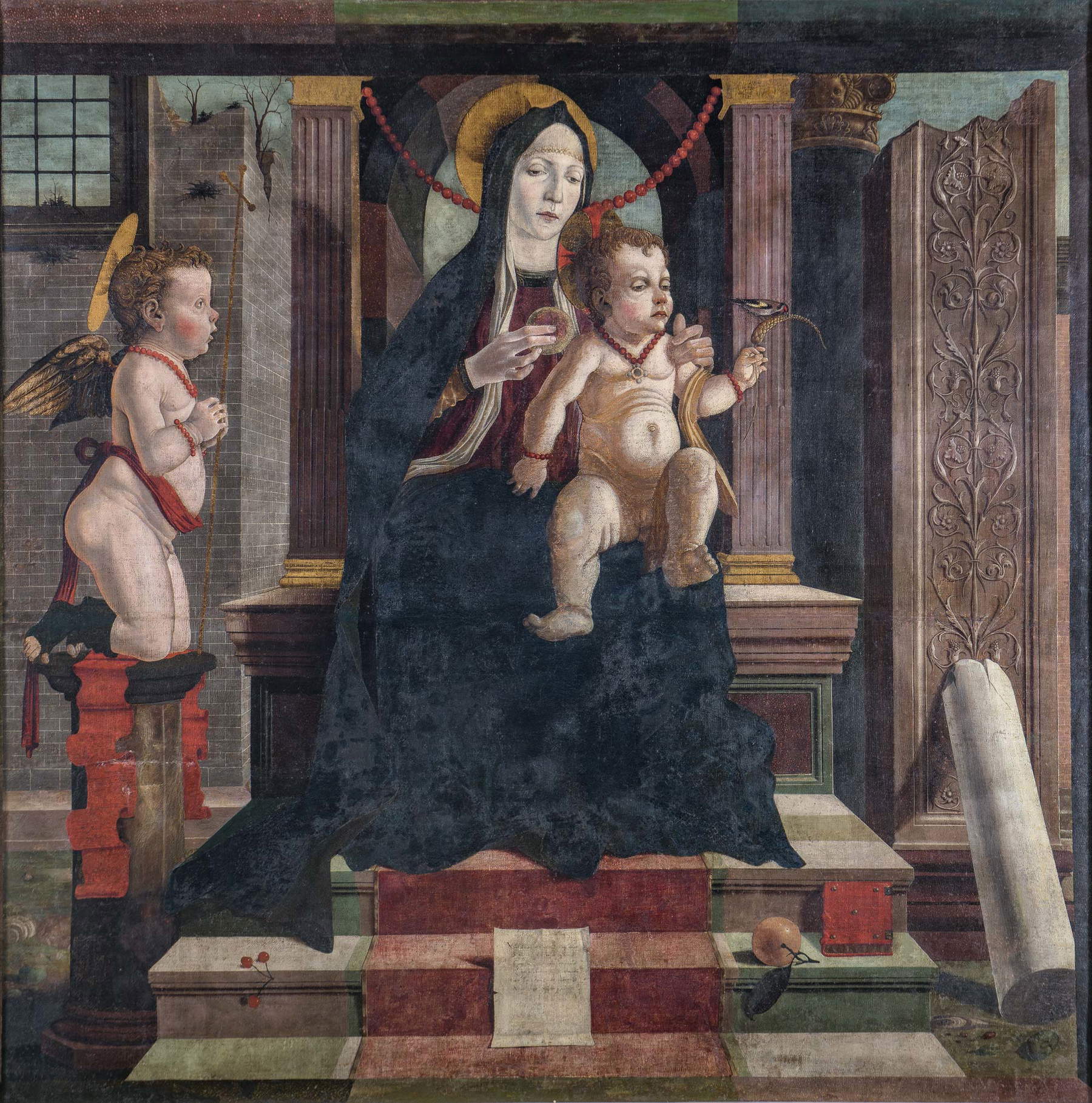

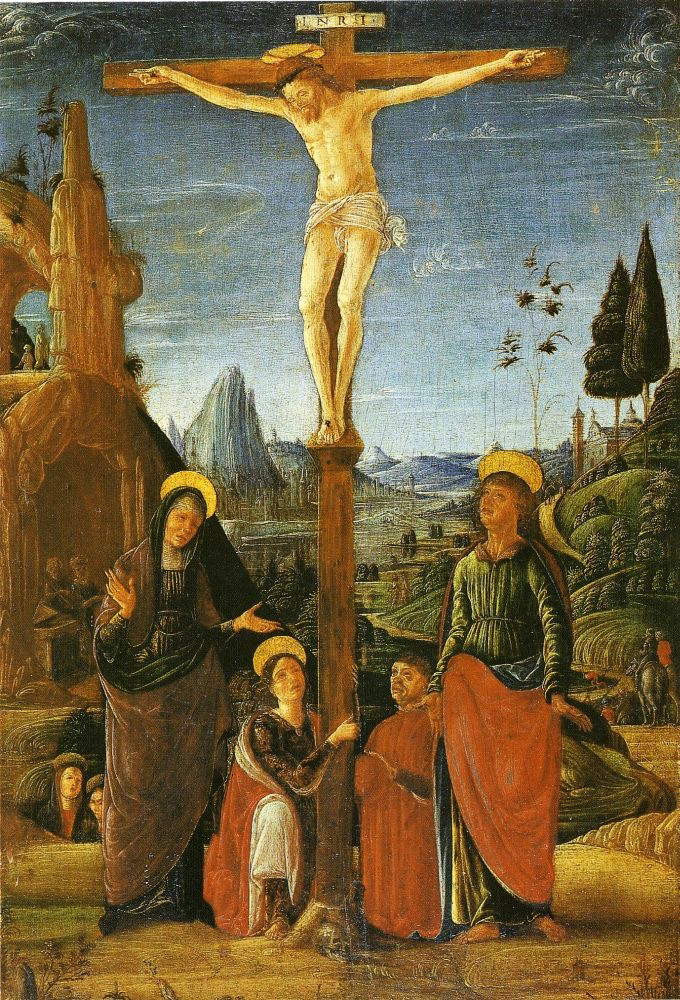

After a room illustrating the vicissitudes of Ferrara painting in the late 15th century to give an account of the city’s artistic and cultural vibrancy (of note is the presence of the Dormitio Virginis from the Ambrosiana in Milan, for which the exhibition does not, however, solve the enigma regarding autography, but Valerio Mosso notes “intriguing affinities” with the Veronese Francesco di Bettino, though without making an attribution), the chapter of the exhibition on Lorenzo Costa opens, which begins with a section devoted to his early years, and is one of the best-performed in the show. Costa, from Ferrara, approached Ercole de’ Roberti from the very beginning (although it is not possible to ascertain a frequentation between the two), and he was probably the only artist of his generation capable of measuring himself against Roberti’s inspiration and revisiting it according to his own original inclination: this is what the exhibition intends to demonstrate in a room that opens with the Crucifixion from the Lindenau-Museum, a work known only from 1845, and first attributed to Costa by Roberto Longhi. It is a work that reveals all the characteristics of Ferrara painting and is therefore to be placed at a date before 1483, the year in which Lorenzo Costa moved to Bologna and his language was affected. The artist also shows that he possesses a marked narrative verve in the Stories of the Argonauts, four of which are brought together for the first time on the very occasion of the exhibition: these are paintings that attest to a full understanding of Ercole de’ Roberti’s language, which is still capable of being revived in the more sculptural pieces of the Saint Sebastian lent by the Uffizi, which is nevertheless also a work of supreme sweetness to be placed in the 1490s, when the artist shows that he has assimilated the delicacy of the art of Francesco Francia, who at that height was the greatest painter in Bologna. The same is true of one of the most beautiful works in the exhibition, the Holy Family from the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon, where the Ferrarese roughness that distinguishes, for example, the figure of St. Joseph, and the supreme grace that gives life to the figure of the very tender Child coexist in total harmony. Acting as a watershed is a masterpiece such as the Pala Rossi, which comes from the Basilica of San Petronio, praised already by Vasari, and which “shows all the richness of Costa’s expressive horizon and his lucidity of assimilation,” as Danieli reiterates, since one finds here reminiscences of Roberti (the throne above all), a compositional structure that looks to Francesco Francia, Flemish minutiae and even a Venetian luminosity, so much so that several scholars have advanced the hypothesis of a stay by Lorenzo Costa in the lagoon.

In the next room, several works by Francesco Francia preserved in private collections provide useful terms of comparison, and the same is true of three panels by Perugino (theArchangel Gabriel and two predella compartments, all works from the late phase of Pietro Vannucci’s career, and all on loan from the National Gallery of Umbria), functional to open the discourse concerning Lorenzo Costa’s updating of central Italian painting, which so much misfortune has brought him in the past, since critics have read this change of orientation of his as a sort of renunciation of the vigor that had characterized his youthful years. The exhibition, through a decidedly important selection, aims instead to present to the public the thesis that, on the one hand, Lorenzo Costa, by approaching Perugino, nevertheless proved himself to be a modern painter who looked to a painting that had imposed itself at the taste of the patrons, and on the other hand maintained a certain independence and a good degree of originality testified by a path that was anything but linear. So if the Madonna and Child with Saints Petronius and Thecla is perhaps the most Perugian Lorenzo Costa had produced up to that point, the slightly later Pala Ghedini, on the contrary, denotes a rapprochement to the ways of Hercules, with that very high throne under a loggia in perspective and that opens on the base to show, as in a kind of television screen, the landscape behind, an obvious reminder of the Pala Portuense. And the same goes for the predella of the altarpiece of Santa Maria della Misericordia in Bologna, anAdoration of the Magi now at the Pinacoteca di Brera and which in the exhibition is reunited with some of the panels of the ancient dismembered machine: Danieli rightly defines theAdoration as a “small masterpiece of ornate Peruginism, where the slender and lively figures of Ercole de’ Roberti adopt the central Italian grace of a Pinturicchio, who at those dates had also seduced Amico Aspertini.” Also close to theAdoration of the Magi is the delicate Holy Family that arrives from the Museum of Art in Toledo, Ohio, a work “skillfully set up through the succession of planes that, in addition to ensuring a sense of space, direct the viewer’s gaze first to the lively Child climbing on his mother’s legs, then to the parents adoring him, and finally to the enchanting natural scenery” (thus Pietro Di Natale).

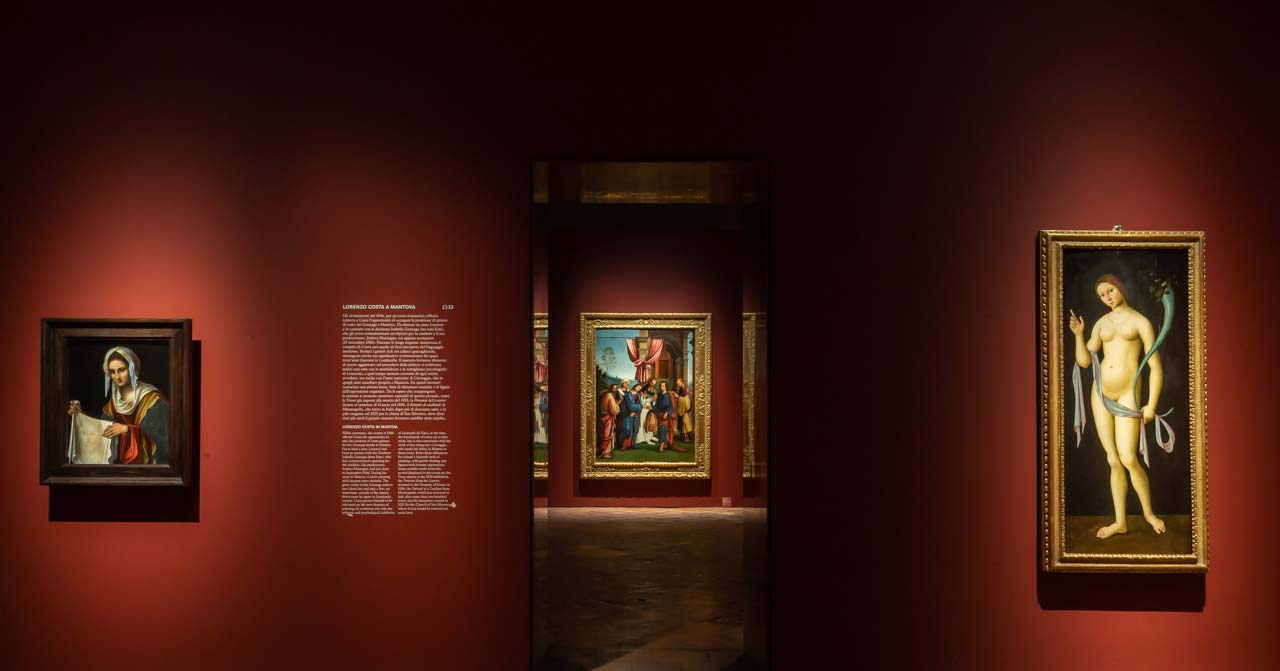

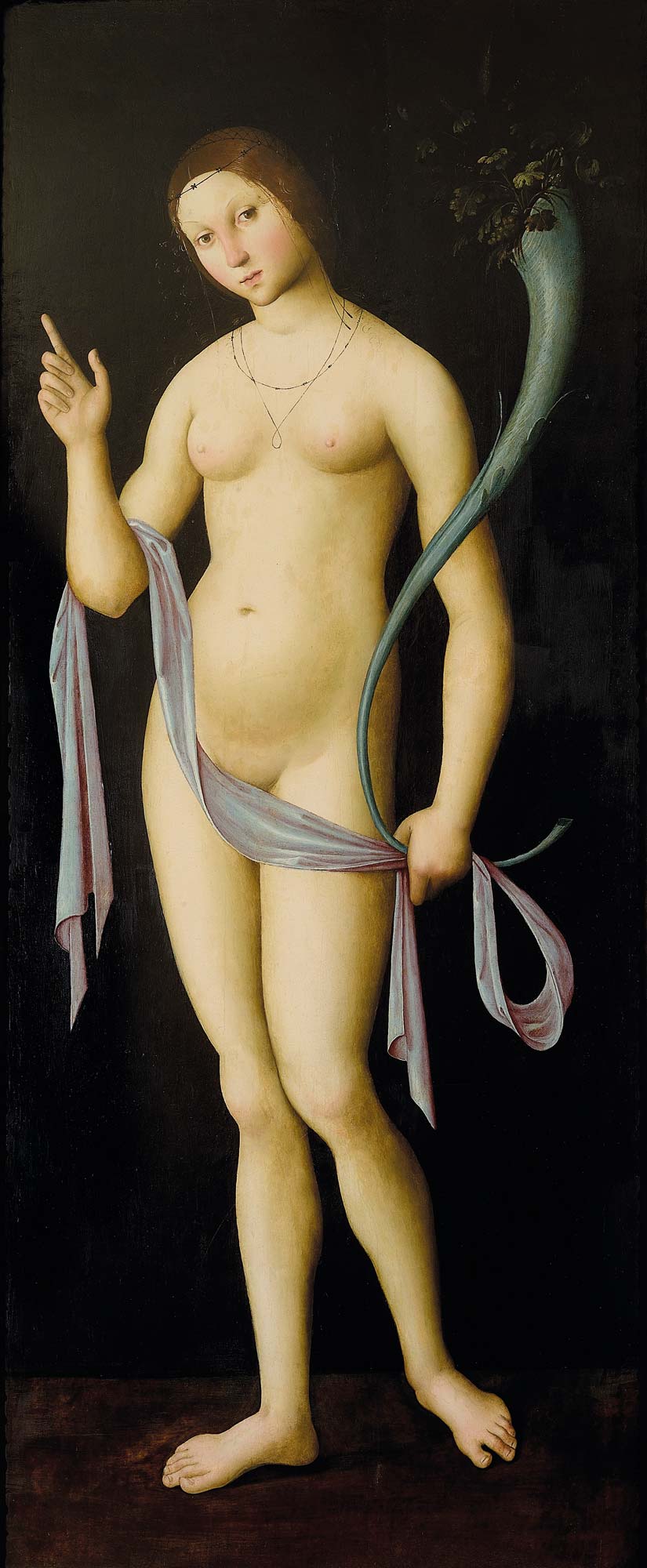

Closing the exhibition, before the final appendix on the fortunes of Ercole de’ Roberti, is the room on the last season of Lorenzo Costa’s career, the Mantuan one, which began in 1506 when the artist was called to the banks of the Mincio River by Isabella d’Este to replace Andrea Mantegna, who had just died. Costa did not wait, given also the changed political situation in Bologna, with the fall of Giovanni II Bentivoglio. In the catalog, the reconstruction of the last thirty years of the Ferrara painter is entrusted to Stefano L’Occaso, a great connoisseur of things Mantuan, who notes, however, the impossibility of arriving at complete conclusions, since many of the works to which the artist aspired in those years have been lost (in Palazzo Sebastiano, for example, there was a “Camera del Costa,” which must have been of supreme significance if one thinks that very rarely do ancient sources use, to indicate the room of a palace, the name of a painter responsible for its decoration). And it will then have to be considered that almost everything of Lorenzo Costa’s that was in Mantua and could be moved, is now found elsewhere: in the city the only important work left is the St. Andrew Altarpiece, a work of 1525 in which the artist seems almost to recapitulate everything he had learned throughout his career, a work preserved in the Albertian basilica as well as another exceptional loan for the exhibition (in fact, it can be admired in the last room), while nothing is left in the public collections. Among the most significant works in the last room is the recently resurfaced Veronica purchased from the Louvre in 1989: it is a painting that was commissioned directly by Isabella d’Este as a diplomatic gift to be sent to France. “The work,” notes L’Occaso, “would [...] have had to compete with the quality of a painting by Mantegna, but different characteristics were recognized in it, a different way of painting, softer and more delicate”: the somber background and blurred outlines in fact demonstrate a fascination for Leonardo da Vinci’s paintings. Among the various works that make up the last section of the exhibition, a work with an obvious Correggesque character, namely the Portrait of a Cardinal from the Minneapolis Institute of Art, which thus testifies to the breadth of Costa’s horizons even in the extreme phase of his career, and the statuesque yet soft Venus on a dark background, which conveys to us a rather accomplished idea about the canons of beauty of the time, deserve mention.

At the Palazzo dei Diamanti, the public has the opportunity to visit an exhibition of an international nature, with a strong scientific structure, a well-considered selection and an impeccable organization, which took a couple of years to prepare and which ended up putting together the most extensive monographic exhibition ever organized on Ercole de’ Roberti (about twenty of his works are present, and calculating how limited his catalog is and how delicate his paintings are, one could already express a positive judgment even just by looking at the numbers) and an updated rereading of the entire parable of Lorenzo Costa (who comes out not as a mere follower, and much less as an artist of secondary importance, but as one of the highest interpreters of that season, as a strong and original painter), all following a project that shows towards traditional studies, starting with Longhi’sOfficina ferrarese, a great respect. The catalog is also good, a useful tool not only for keeping up to date with the readings the exhibition offers on the topics it addresses, but also for recapitulating what we know about Ercole and Lorenzo, with an introduction by Vittorio Sgarbi, essays by Giovanni Ricci, Marcello Toffanello and Roberto Cara, and the many contributions by Michele Danieli, Valerio Mosso, Valentina Lapierre and Stefano L’Occaso that make up a solid and lengthy framework within which the works’ files are arranged. A beginning, then, that bodes well for the continuation of the Renaissance in Ferrara project, with subsequent stages that will investigate the entire sixteenth century Ferrara until 1598, the year of the Devolution of Ferrara to the Papal State.

Lastly, we cannot fail to mention the renovated spaces of the Rossetti wing and the Tisi wing, united by the project of the architectural firm Labics, which, inside the rooms, has revised the surfaces and floors, inserted special burnished brass portals that present the visitor with fascinating mirror effects that offer the sensation of being inside a much wider and longer wide and long than it actually is, revolutionized the reception areas, starting with the bookstore and the new cafeteria, all set up in the premises of the former Risorgimento Museum, and above all created a connection between the two wings. Where there used to be a sort of temporary walkway that exposed visitors to the cold in winter, there is now a wooden structure with large windows with continuous views of the palace’s large garden, also newly built. This is a decidedly lighter and less impactful solution than the initial design that was met with lively controversy. A solution that contributes to making the Rossetti and Tisi wings an even more modern and welcoming museum venue. It is ideal for hosting a long project on the Renaissance in Ferrara with an international scope.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini

Nato a Massa nel 1986, si è laureato nel 2010 in Informatica Umanistica all’Università di Pisa. Nel 2009 ha iniziato a lavorare nel settore della comunicazione su web, con particolare riferimento alla comunicazione per i beni culturali. Nel 2017 ha fondato con Ilaria Baratta la rivista Finestre sull’Arte. Dalla fondazione è direttore responsabile della rivista. Nel 2025 ha scritto il libro Vero, Falso, Fake. Credenze, errori e falsità nel mondo dell'arte (Giunti editore). Collabora e ha collaborato con diverse riviste, tra cui Art e Dossier e Left, e per la televisione è stato autore del documentario Le mani dell’arte (Rai 5) ed è stato tra i presentatori del programma Dorian – L’arte non invecchia (Rai 5). Al suo attivo anche docenze in materia di giornalismo culturale all'Università di Genova e all'Ordine dei Giornalisti, inoltre partecipa regolarmente come relatore e moderatore su temi di arte e cultura a numerosi convegni (tra gli altri: Lu.Bec. Lucca Beni Culturali, Ro.Me Exhibition, Con-Vivere Festival, TTG Travel Experience).

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.