To give an idea of the uniqueness of an exhibition featuring Pisanello as its protagonist, it will suffice to recall that twenty-one years have passed since the last exhibition dedicated to him (at the National Gallery in London, in 2001), and that in the last fifty years there have been only three events centered around his figure (in addition to the London exhibition, there were two in Paris and Verona in 1996). The main drawback that weighs on this artist today, wrote Joanna Woods-Marsden reviewing the National Gallery exhibition in Renaissance Quarterly in 2002, lies in the fact that his art is hardly accessible by the museum-going public because little of him has survived: suffice it to say that the exhibition Pisanello. The Tumult of the World, a new chapter in Pisanello’s exhibition history that opened last October 7 at the Ducal Palace in Mantua, curated by Stefano L’Occaso, gathers together practically half of the known mobile production of this “Raphael of his time” (the definition is still Woods-Marsden’s), excluding drawings and medals. The occasion for an exhibition in the city of the Gonzaga is given by an anniversary: this year marks the fiftieth anniversary of the presentation to the public of the wall paintings of the "Pisanello Room,“ discovered in the 1960s and returned to the community by Superintendent Giovanni Paccagnini. A ”hard-earned“ discovery, as Cesare Brandi called it (for whom Pisanello was a ”luminary and elusive artist, both ancient and new“), and thus perhaps there was ”none more laborious and deserved than this." The exhibition accompanies an enhancement of the Tournament of Knights, conceived by L’Occaso himself and designed by the Mantua territorial pole of the Milan Polytechnic, with supervision by Eduardo Souto de Moura: new lighting that enhances every detail of the cycle, a raised platform to bring visitors to the height of the floor as it was in the 15th century, at the time of Pisanello, and digital tools that show the public the room as it was before the tearing of the 18th-century frieze with the effigies of the dukes of Mantua and the neoclassical paneling that had altered the appearance of this room.

That discovery, made possible by Paccagnini’s insight and persistence (a plaque affixed in the room commemorates him), was one of the most extraordinary of the last century, and it is rightly remembered with an exhibition worthy of its importance, set up partly under Pisanello’s paintings and partly in the rooms of the Santa Croce apartment. We have already mentioned the enhancement of the Tournament of the Knights and everything related to it on these pages: the exhibition, however, is not a mere filler, an addition to be dismissed in a few lines in the face of the considerable work that has been done to give new legibility to the Pisanello room, and which will remain even when all the works loaned for the exhibition have reached their institutions. It is, on the other hand, one of the most important exhibitions to be held in Italy this year, first and foremost because it is the only one that can be set up in a place where Pisanello worked directly on walls (unless one imagines improbable exhibitions inside Veronese churches): an element capable of guaranteeing to the exhibition a completeness to which neither the Paris-Verona exhibition of 1996 nor the London one five years later could aspire, and it is significant that, at the press conference, this aspect was first of all acknowledged by Dominique Cordellier, who curated the Louvre exhibition twenty-six years ago. Then, because it gives a way to bring to the rooms on the ground floor of the Ducal Palace a selection of works that is extremely useful in lowering the visitor, even those who know little about the period in which Pisanello worked, into the context of Mantua at the beginning of the fifteenth century, and to essay its fertile artistic vitality. And again, it is a relevant exhibition because of its international dimension: loans of the highest order arrive in Mantua, as will be seen later.

The novelty of the project is to be found first of all in the approach that has been given to the exhibition: the two exhibitions of 1996, with more than a hundred pieces (including paintings, drawings and medals), were intended to offer the public an overall reading of Pisanello’s artistic and cultural development. The one in London, much less extensive than the previous two, focused on the relationships between Pisanello and his patrons. In contrast, the new exhibition organized in Mantua focuses, on the one hand, on the paintings in the Pisanello Room that dialogue with a large nucleus of drawings displayed below the works on the wall, and on the other on the context from which the Tuscan painter’s masterpieces arose.

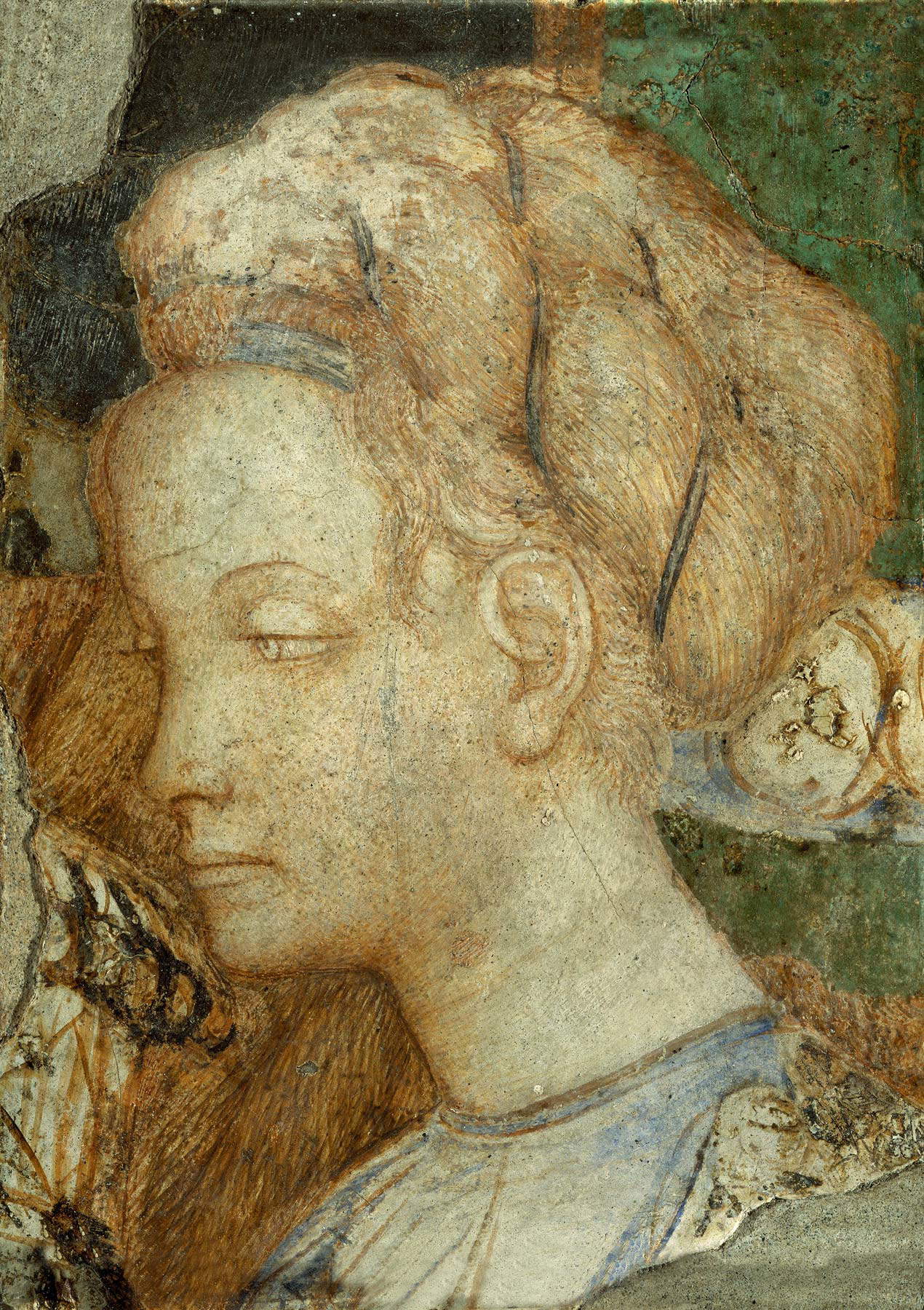

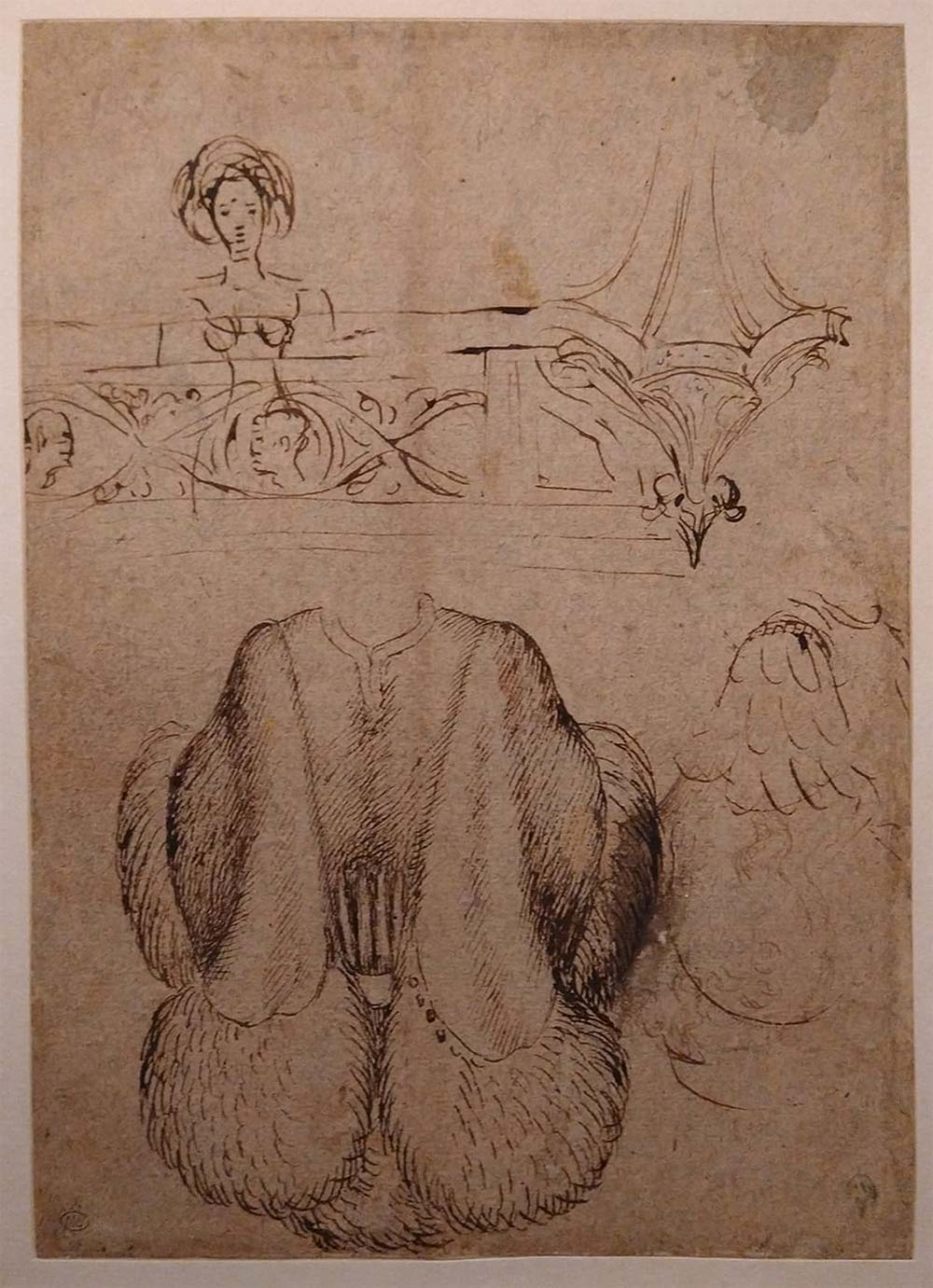

The exhibition begins right in the Pisanello room, with a nucleus of works (including drawings, paintings and medals) related to the intervention that the artist performed on the wall of the room: one of the most remarkable pieces of the exhibition stands out in the original setting designed by Archiplan Studio, the Head of a Woman on loan from the Museum of Palazzo Venezia in Rome, whose, moreover, curious coincidence, we celebrate this year the centenary of its entry into the state collections (it was 1922 when this fragment of a fresco was acquired by the state). We do not know the original location of this fragment (it has been speculated, in particular, that it came from the Stories of the Baptist begun in San Giovanni in Laterano by Gentile da Fabriano and then continued by Pisanello), nor do we know for certain who it represents: the most probable idea, also reiterated at the Palazzo Ducale exhibition, is that this lady was part of a more or less crowded group, of those sometimes encountered in Pisanello’s paintings. It is displayed in the exhibition because of the close resemblance it bears to the lady in profile painted by Pisanello in the box that can be admired in the upper left-hand corner of the room in the Doge’s Palace, so much so that some scholars have advanced the supposition that they were taken from a single preparatory drawing: they are silent and vivid witnesses to Pisanello’s fairy-tale world, to the courtly atmospheres of his paintings. The Palazzo Venezia fragment is surrounded by a selection of drawings in some cases directly related to the Torneo dei Cavalieri. This is the case, for example, with folio 2275 in the Louvre, where we see a female figure similar to those we find in the ladies’ box on the wall. It has no direct connections, but is of supreme utility, folio 2278, considered, writes Margherita Zibordi in the catalog, “among the most important for shedding light on the chronology” of Pisanello’s works. In fact, a coat of arms appears on the sheet, that of the Gonzaga family framed with the two Bohemian lions that were granted in 1394 by Emperor Wenceslas IV: Pisanello saw it reproduced in marble at the Ducal Palace, and since the coat of arms in question was in use until September 1433, the sheet could only have been executed before that year, which is why we are almost certain that these studies belong to Pisanello’s Mantuan period.

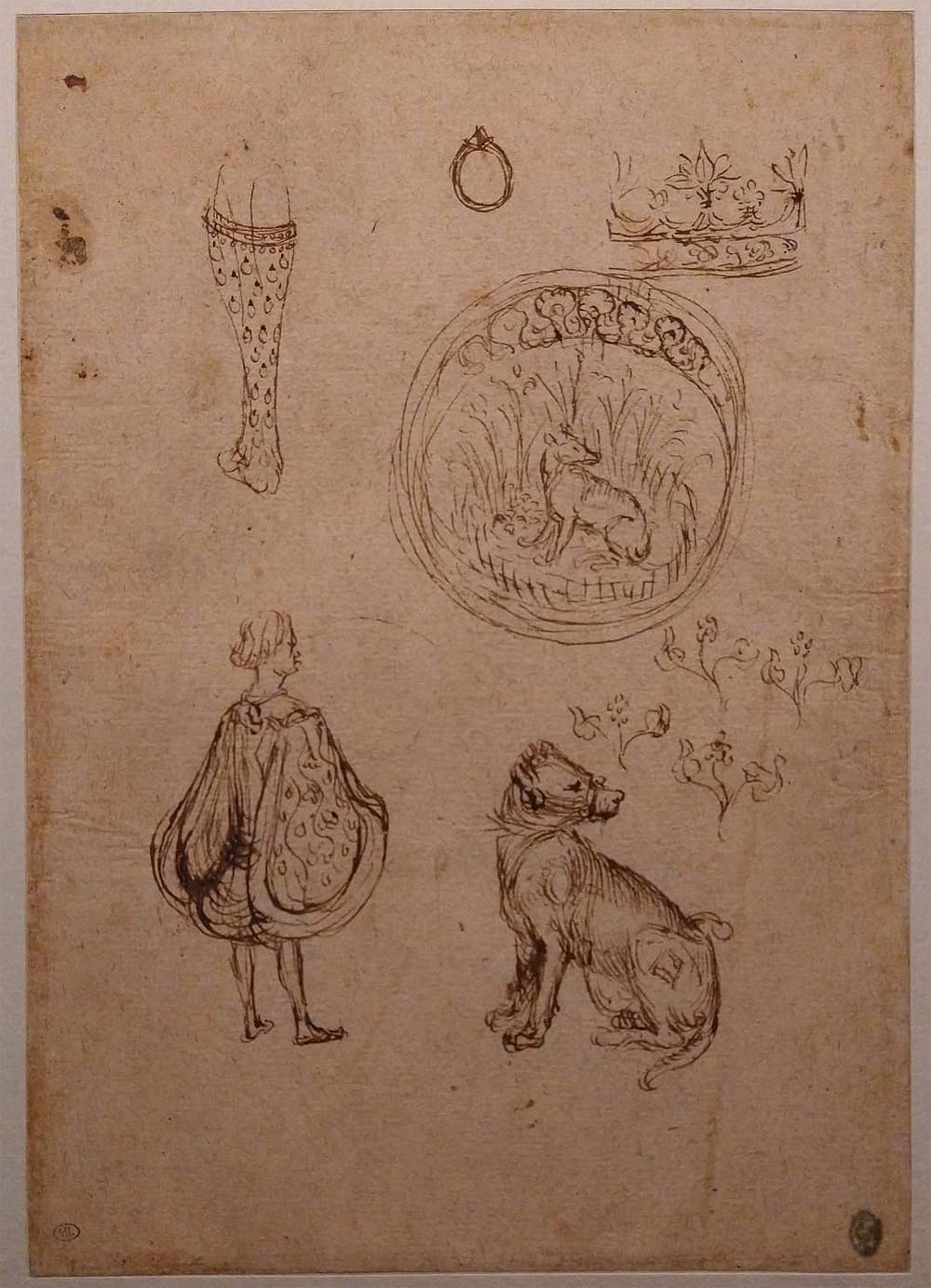

Looking again at the sheets that Pisanello drew in preparation for the Tournament of Knights, we can appreciate with some curiosity the 2300 in the Louvre, dominated by the figure of a man blowing to play a trumpet, and which we find again precise on the wall paintings: note the realism, almost grotesque, with which Pisanello, who was in all likelihood the most observant and inquisitive of the painters of his time, studies the appearance the character’s face takes on during the action. They are often chaotic sheets: evidence of this is the fact that Pisanello uses the character’s hat to sketch a horse, not to mention the tiny sketch we observe in the upper left corner, interpreted since the 1960s as a study for an altarpiece. Admiring Pisanello’s drawings thus allows us to become familiar with the painter, to see him at work, to know the effort he put into studying the details of each composition, into elaborating ideas, into proceeding by experimenting, as happens in folio 2280, a fantasy landscape with a castle in the foreground and some mountains in the background, which reveals some affinities with the sinopias of the Ducal Palace room, and as happens even more clearly in a workshop sheet that arrives on loan from the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, where we admire a man encased in a thick fur coat in the fashion of the early 15th century, depicted according to different poses and angles: these are most likely, Zibordi explains in the catalog, depictions of the Hungarians in the court of Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg, who came to visit Mantua in 1433. An event of fundamental importance, as much for its political implications (the emperor came to the banks of the Mincio River a first time in 1432 to grant the title of marquis to Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, and a second time in 1433 to renew the concession) as for its artistic and cultural ones (it is thought that the accuracy of the sinopites depended on the need to have to present the wall paintings in a state of such fineness that they could be considered worthy of welcoming the sovereign). Also on display in the exhibition are other objects related to Sigismondo’s visit and, more generally, to Pisanello’s illustrious commissions: we find, for example, a profile of the emperor executed by Pisanello on the occasion of the visit, displayed not far from a singular sheet from around 1440, on loan from the Fondation Custodia, featuring an Este knight with a very wide fur-lined headdress and a falcon on his glove. It is, in particular, a drawing marked by a very high degree of finish (there are also gildings on the spurs of the knight), and thus has “a presentational character,” as Andrea De Marchi writes, who points out that the knight represents not so much a realistic depiction (“one certainly did not go hunting so sumptuously harnessed and much less mounting a mule”), but rather a representation of an image pleasing to the knights, of a way in which they liked to appear. The visit to this section of the exhibition concludes with the display of a number of medals, including that of the commissioner of the wall paintings, Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, although, Giulia Zaccarotto points out, “the close iconographic assonance with the chivalric cycle of the Palace is not sufficient to consider the medal an early production by Pisanello, and it is precisely for stylistic reasons that it must be placed at least in the mid-1440s” (the paintings, on the other hand, most likely date from between 1430 and 1433).

Descending to the Santa Croce apartment, one is greeted by a Madonna del Latte by an anonymous Cremonese artist, part of the collections of the Ducal Palace, and included at the start of the concluding section of the exhibition to provide the public with an eloquent example of the late Gothic language that characterized the Mantuan context in the years when Pisanello would have been working in the city: it is, in this case, the fragment of a fresco detached from a house in the historic center, which, moreover, had already been selected for the 1972 exhibition on Pisanello, the one organized by Paccagnini to present the discovery of the wall paintings. A work that has raised lively discussions about the area in which it might have been produced, it best exemplifies those atmospheres of detached refinement and courtly elegance (see not only the expression of the Virgin, with that gaze at once sweet and haughty, her ivory complexions brightened here and there by slight blushes or the slightly elongated proportions, but also certain details such as the fur-lined cuffs, or the decoration of the halo imitating punching) that are found in all the works of the period, beginning with those in the next room: arrives from the Pinacoteca di Brera, in fact, the splendid Adoration of the Magi by Stefano da Verona, almost coeval with Pisanello’s wall paintings. It is a painting that best sums up the characteristics of the International Gothic: the preciousness of the decorations, with even the use of gilded finishes, or the verism in the description of the botanical elements (typical, this, of the late Gothic of the Lombard area), the stylized landscapes that seem almost to have come out of a dream, the sinuous draperies that wrap bodies of elongated proportions almost to excess. Add to this, in theAdoration of Stefano da Verona, a naturalism in the investigation of the faces of the characters that cannot fail to recall Pisanello’s earlier trials in Verona. Some of the characters directly recall those in the small crowd of the St. George and the Princess in the church of Santa Anastasia, a work that Stephen evidently knew well, if we consider it plausible, given the presence of St. Anastasia next to St. Joseph in the Brera panel, that the work comes from the very same complex in which Pisanello painted his masterpiece.

Pisanello, moreover, is present in the same room with a pair of drawings related to the small room that houses them. Drawing 2277 in the Louvre presents some studies for the feat of the Great Dane dog (one of the symbols that made it possible to trace the wall paintings discovered by Paccagnini back to the commissioning of Gianfrancesco Gonzaga, and which we find not only in Pisanello’s sinopia, but also in the frieze in this room of the Santa Croce apartment), which appear in the sheet along with some sketches of blades of grass, the image of a leg wearing an elaborate, jewel-embellished footwear, and a study of a figure covered in a heavy, fashionable cloak. And turning one’s gaze to the ceiling, one cannot help but notice the resemblance of the painted loggia to the one drawn on sheet 2276: an architecture reminiscent of those of Venice, the city where Pisanello worked for a long time, employed in the decorations of the palace of the doges, and a city that also had some relationship with Mantua, as we are reminded by the Saint Benedict tempted in the desert near Subiaco by Niccolò di Pietro, a Venetian painter who executed this panel as part of a polyptych of which three other panels are known today, all in the Uffizi. The polyptych in question was almost certainly destined for a Benedictine monastery in the Mantuan area (perhaps the abbey of Sant’Andrea, or the monastery of Polirone in San Benedetto Po, explains Michela Zurla), and it bears witness to the liveliness of the Mantuan artistic environment in the turn of the years on which the exhibition focuses. The presence in the exhibition of the sumptuous Missal of Barbara of Brandenburg (actually commissioned by Gianlucido Gonzaga, Gianfrancesco’s son, and not by Ludovico II’s wife, as the insignia on the codex might lead one to think), a masterpiece by Giovanni Belbello da Pavia, is moreover functional in suggesting to the public all the floridity of artistic life in early fifteenth-century Mantua.

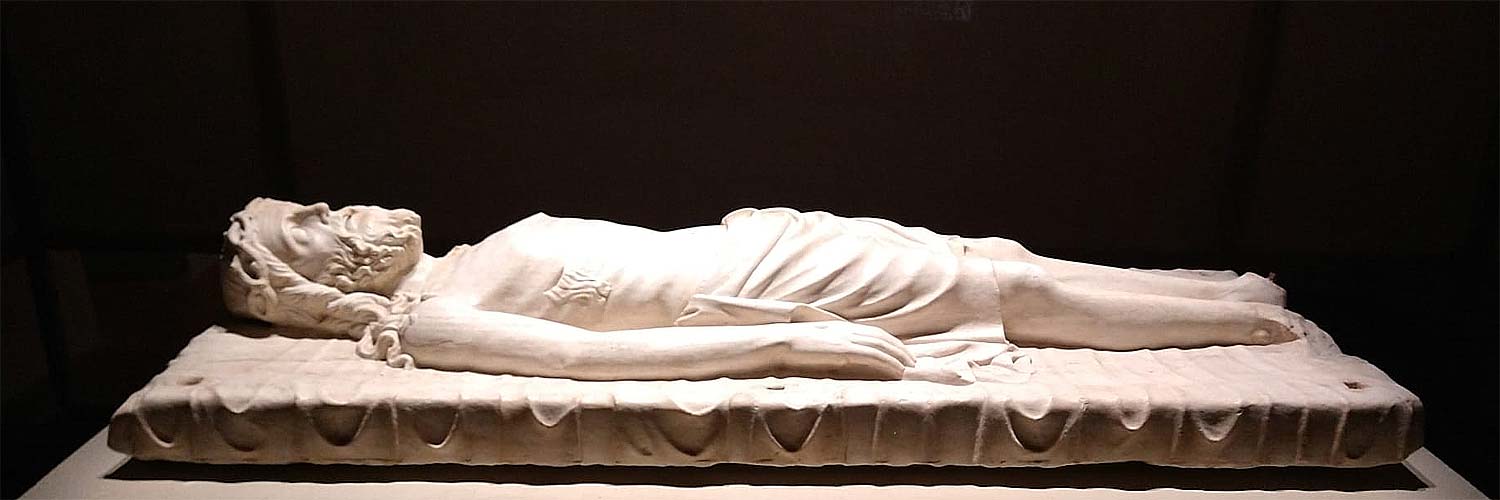

The same could be said for the brief but valuable focus on sculpture, which makes use of Archiplan’s original open arrangements, designed to encourage comparisons between sculpted and painted works, and to tighten the interweavings between the different rooms. The selection that curator L’Occaso has deployed in the rooms reserved for sculpture is of the highest level (as it is in the other rooms: one of the merits of the exhibition at the Ducal Palace is the absence of any lapse in quality): it begins with a St. George by Filippo di Domenico da Venezia, originally part of the decorative apparatus of Mantua cathedral and indebted in respect to the ideas of Pierpaolo dalle Masegne (the pose, moreover, recalls that of Tullio Lombardo’s Young Warrior, a work of about eighty years later); it continues with a hieratic Madonna and Child by the same author (his works, writes Vera Cutolo in the catalog, “compel a search for stylistic models that plumbs a very wide perimeter,” from late Gothic Venetian sculpture to the site of San Petronio in Bologna), also originally in the cathedral and then moved in the seventeenth century to the parish church of Villa Saviola, and ending with two works of vivid intensity such as Christ in Pity by Michele dello Scalcagna, a Florentine artist who trained in Tuscany and then moved to northern Italy, where he worked for a long time, executing, among other works, this Christ marked by tangible dramatic tension, and with Jacopino da Tradate’s Dead Christ from the church of San Francesco in Casalmaggiore, originally part of a larger Lamentation.

Among the sculptures, two smaller rooms, set up to give the public the feeling of a sort of precious, surprising loop in the exhibition itinerary, house Pisanello’s two masterpieces, the Madonna of the Quail and the Madonna and Child with Saints Anthony Abbot and George. One work precedes and one follows the paintings in the Doge’s Palace: some 20 years separate the work arriving from Castelvecchio, circa 1420, and the one arriving instead from the National Gallery in London, painted around 1440. Refinement, refined luministic effects, abundance of details, luxurious gilding clash with some uncertainties typical of a young painter (the disproportionate Child, the imprecise nimbuses, “the routine rendering of plant elements,” as Luca Fabbri writes in the catalog) and which have provided arguments in the past to question the attribution of the painting to a “usually very controlled master” as Pisanello would later prove to be. Some elements discernible in other certain works, however, lead one not to doubt the authorship of a work of great quality. In the next room, enclosed by its nineteenth-century frame inspired by Pisanello’s medals, here instead is the Madonna from the National Gallery, an exceptional painting: it is the only moveable work signed by the artist (the signature “Pisanus” can be seen at the bottom), and it is exhibited for the first time in Italy. In fact, the panel reappeared on the market in the 1860s, when it was purchased by Sir Charles Eastlake in 1862 and then donated, five years later, to the London museum. A work that, L’Occaso explains in the catalog, "finds discrete affinities with the [...] San Giorgio veronese, whose execution may not be too far removed from 1438," may have been inspired, according to Anna Rosa Calderoni Masetti, by a jewel purchased in 1450 by Leonello d’Este (the panel is probably of Este origin), recalled by the tondo with golden rays in which the figure of the Madonna tenderly holding the Child to herself finds space. The originality of the solutions, from the gilded disk to the forest that serves as a backdrop for the characters, from Saint George’s back pose to his elegant and abundant armor, to the horse that invades the space with its muzzle as it enters from the right, combined with the possibility of admiring a Pisanello who evidently questions Renaissance innovations by completely renouncing the gold background and attempting to orchestrate a scientifically credible space, add to the reasons why the National Gallery panel is one of the pinnacles of Pisanello’s production. And its presence in the exhibition is one of the main reasons to go to Mantua to visit it.

The exhibition is completed by a rich catalog that concentrates especially on the wall paintings and on the related sinopites, which have undergone new investigations that are punctually accounted for in the many essays that line the pages of this valuable publication, as well as in an accurate photographic campaign returned to the public in the form of a remarkable atlas that allows one to appreciate even the most minute details of what has remained in Pisanello’s room. In addition, a section in the Hall of the Popes further illustrates the stages that led to the discovery of the paintings by recounting in detail the story of Giovanni Paccagnini and his fundamental discovery, which would also procure him the gold medal of the Presidency of the Republic for meritorious achievements in culture and art, the National Prize of the Accademia dei Lincei, and even a toponymic recognition, since the city of Mantua would dedicate to him the square located near Piazza Pallone.

Two years of work were needed to bring Pisanello to the public. The Tumult of the World, an exhibition of small size (about 30 works on display in all, but all of high quality) and therefore fast-paced, free of misplaced works, an event of international caliber, which enters fully into the most important history of studies on Pisanello and on late Gothic artistic culture (since the exhibition extends, as we have seen, also to the context, and the same assumption applies to the catalog), and which ranks among the most significant exhibition appointments of the year in Italy, but perhaps also outside. One of the very few, in short, for which a visit waiver might cause some regret.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.