I make no secret of the fact that, before I crossed the threshold of the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo (on January 4, 2019), I had high expectations for the Antonello da Messina exhibition, curated by Giovanni Carlo Federico Villa, which opened on December 14, 2018, and runs until February 10, 2019. Expectations had risen over the past few months: it was projected to be second to the 2006 major exhibition at the Scuderie del Quirinale and the 2013 exhibition at the Mart in Rovereto, “exhibition of the year,” “flagship event of the Palermo Capital of Culture 2018 calendar,” “almost half of Antonello da Messina’s works on display.” At the exhibition of the autograph works of Antonello da Messina (Messina, 1430 - 1479), I would have expected an iconographic, stylistic reflection and pictorial relations with the language of the Flemish and Venetians, or better yet, with contemporary sculpture and portraiture, well represented in the permanent collection of Abatellis (at no cost): one among all, Francesco Laurana. A study perspective that could take its cue from the unrepeatable, pioneering 1953 exhibition at Palazzo Zanca in Messina(Antonello da Messina e la pittura del ’400 in Sicilia, catalog edited by Giorgio Vigni and Giovanni Carandente with an introduction by Giuseppe Fiocco and layout by Carlo Scarpa), which presented 18 works by the master in connection with the works of painters active between the 14th and 15th centuries. An exhibition, with Salvatore Pugliatti as chairman of the executive committee, involved scholars of the caliber of Ferdinando Bologna, Federico Zeri, Stefano Bottari, Cesare Brandi and Giulio Carlo Argan. Not only exhibition of masterpieces, but reflections and reconstructions of the artist’s pertinent context and cultural milieu: another further example might have been the 1982 Messina exhibition La cultura in Sicilia nel Quattrocento (from February 20 to March 7, 1982) and the Antonello da Messina exhibition (from October 22, 1981 to January 31, 1982) at the Museo Regionale, curated by Alessandro Marabottini and Fiorella Sricchia Santoro, as part of the Antonellian events. We can say it: the Palermo exhibition is a missed opportunity.

Announced as early as the first days of 2018, declaimed with great publicity and journalistic resonance, in reality the exhibition proves to be a “mo(n)stra event” that encapsulates many doubts. At the end of this reflection of mine, we will probably have a bath of reality and realize that such an exhibition has some flaws both from the organizational and the scientific point of view: factors influenced and linked together, the absence (or rather: deficiency) of one has generated a subsidence of the other, a chain effect. One aspect that denotes the primordial disorganization is the announcement, in January 2018, of the exhibition venue and duration: the former was the Salinas Archaeological Museum, the latter planned to open from October 26, 2018 to February 24, 2019, a full four months. It all evaporated in the more consonant Abatellis venue and in the two-month postponement and halving of the opening period, from December 14, 2018 to February 10, 2019, a decision that probably hides deeper motivations.

|

| Entrance of Palazzo Abatellis for the exhibition on Antonello da Messina |

|

| Exhibition hall |

To substantiate the scientific and exceptional nature of the “event,” several statements and news footage appeared during the autumn months announcing the presence of works from Como(Annunciata “Advocata virgo” from the Museo Civico), Rome(Ritratto d’uomo, Villa Borghese), and Turin(Ritratto d’uomo from Palazzo Madama): only the latter two sharp profiles would certainly have helped the reading and contextualization of the Cefalù Portrait, relegated alone to a small room in the exhibition itinerary without any relationship and dialogue with the other portrait in the exhibition(Portrait of a Man from the Museo Civico di Pavia). International loans were also announced, such as Christ at the Column from the Louvre and St. Jerome in the Study from the National Gallery in London, the latter already granted in 2006 to the Regional Museum of Messina in exchange for the two Caravaggios. Only these two masterpieces, if they really came to Palermo, would have given a pregnant significance to the exhibition, especially the St . Jerome. It is worth mentioning that the 2006 Messina exhibition related and dialogued the London panel with the Polyptych of St. Gregory (signed and dated 1473) and the opisthograph panel with the Madonna and Child and a Franciscan in Adoration and Christ in Pity, purchased by the Region of Sicily at Christie’s auction, in the presence, in addition, of theAnnunciation from the Regional Museum of Palazzo Bellomo in Syracuse, which was closed at the time for restoration work. An operation, that, of high scientific value, whose catalog, edited by Gioacchino Barbera, contained texts by Fiorella Sricchia Santoro, Lionello Puppi, Francesca Campagna Cicala and Giovanni Molonia.

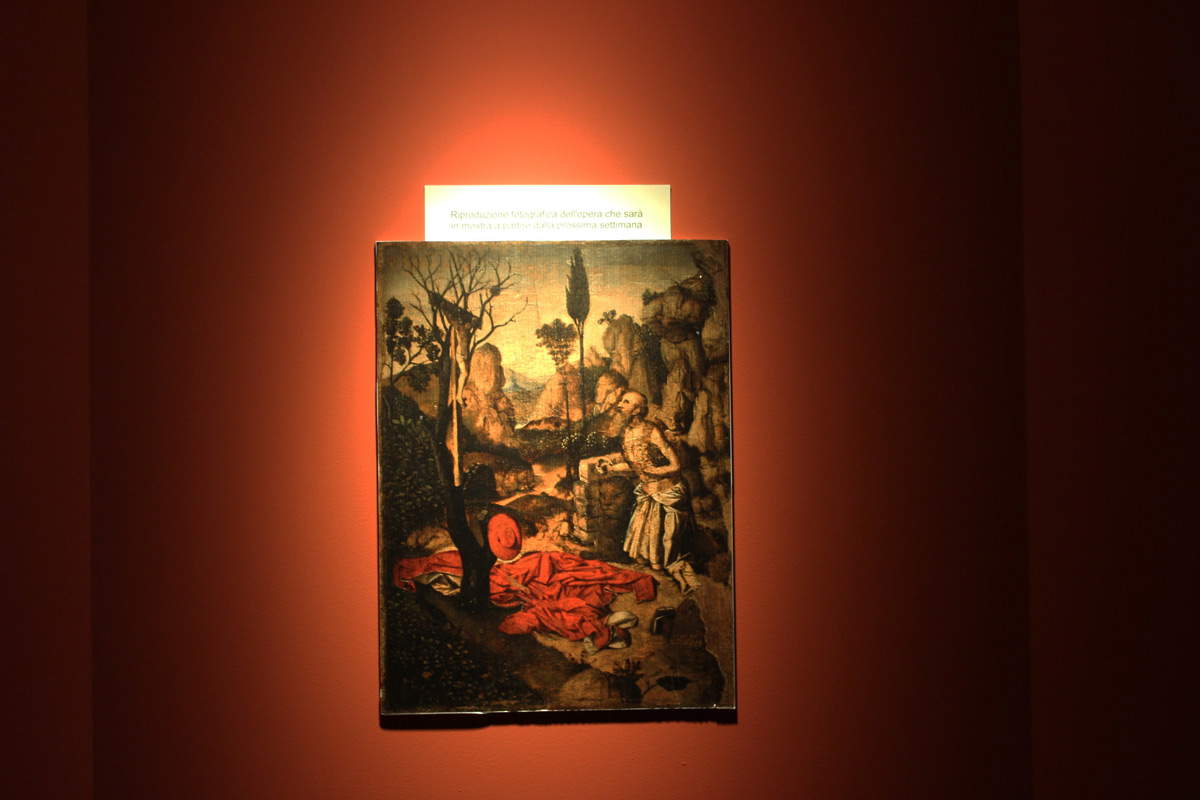

But going back to the acclaimed loans, where did they go? Walking through the exhibition halls, there is no trace of them. In the first room set up to start the exhibition (because theAnnunciation and the Three Doctors of the Church are always in their permanent location, lacking any significant critical and exhibition-related relationship with the display), one immediately notices the ’presence/absence’ of two masterpieces by Antonello: San Girolamo penitente and Visita dei tre angeli ad Abramo (1465-68) from the Museo Civico di Reggio Calabria. Their absence is anticipated by a scotch-taped ’notice’ prominently displayed on a totem before the ticket office that reads “Mr. and Mrs. Antonello are hereby informed. Visitors that the following works are not present in the exhibition itinerary,” and inside the ’monumental vitrine-windows’ the two panels are replaced by the message “Photographic reproduction of the work that will be on display starting next week,” a wording, this, that has been present since the day of the opening (December 14, 2018) and persistent again on the day of my visit (January 4, 2019), when among other things the exhibition catalog (€19) was also absent.

|

| Antonello da Messina, Annunciation (c. 1476; oil on panel, 45 x 34.5 cm; Palermo, Palazzo Abatellis, Regional Gallery) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Madonna with Blessing Child and a Franciscan in Adoration, recto (1463; tempera grassa on panel, 16 x 11.9 cm; Messina, Museo Regionale) |

|

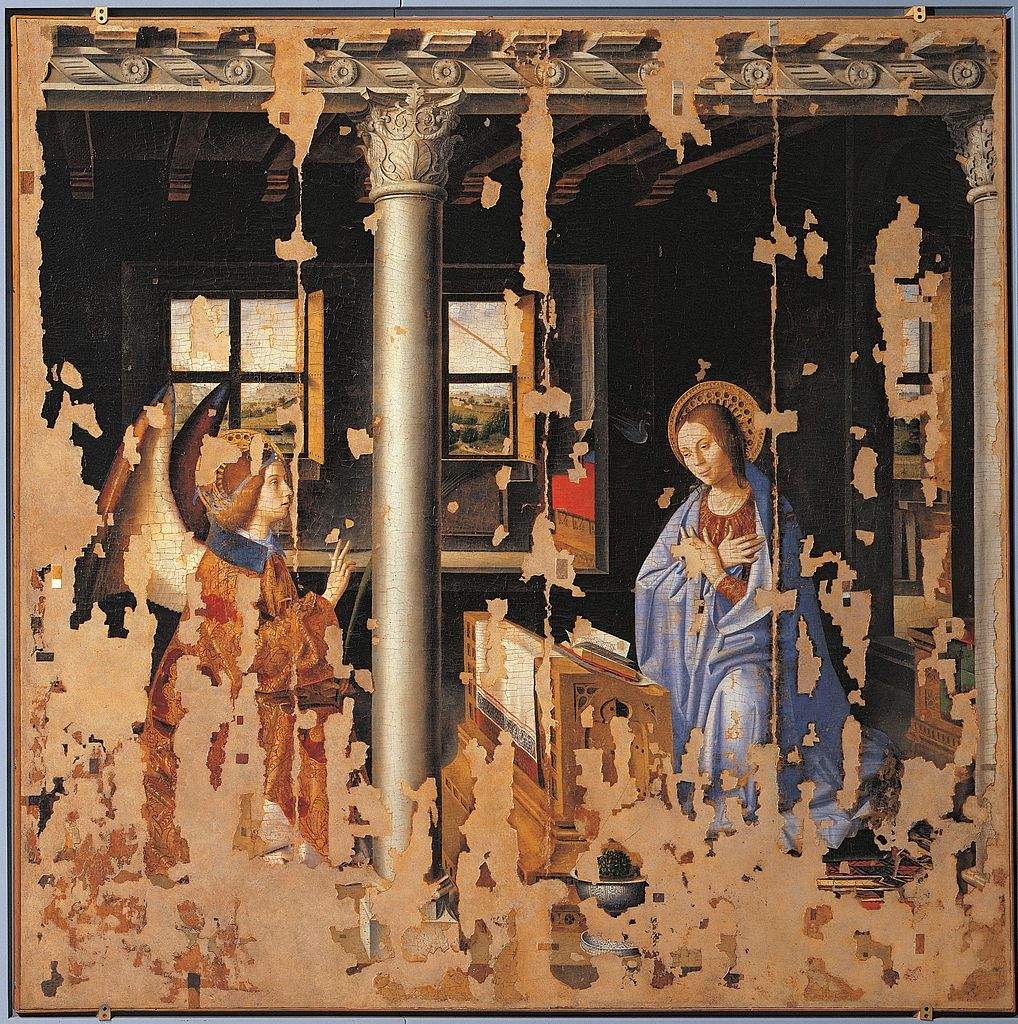

| Antonello da Messina, Annunciation (1474; oil on panel transported on canvas, 180 x 180 cm; Syracuse, Palazzo Bellomo) |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Annunciation, detail |

|

| Antonello da Messina, Annunciation, detail |

I went to the direct source: I made telephone contact with the person in charge of the Pinacoteca Civica of Reggio Calabria, Dr. Amodeo, who has a clear understanding of the whole affair and confirms to me that there were technical-administrative difficulties and delays regarding the too tight timeline of the request for the loan of the two works. A request that, yes, had the approval of the City’s Culture Department, however, there are and remain difficulties with the handling and transportation of the two works for such a short period of time and with the timing of the application that came, it seems, too close to start the bureaucratic machine of the Superintendence, which must screen and supervise this procedure. At this point, by the Pinacoteca director’s own admission, the two panels will never reach Palermo, as it is now four weeks away from closing and almost a month has passed since its inauguration. It is therefore to be assumed that the shifting of the intial opening dates, from October to December, is motivated by delays in the response of some loans, which were not granted, such as those of the Louvre and the National Gallery, and by organizational swerves such as the case of the Reggio Calabria plates.

One question arises: to whom does the revenue from the entire ticket sales revenue go, in addition to the revenue from the sale of the catalog (available only from January 6, 2019)? Is there an agreement, a memorandum of understanding between Vivaticket, which is in charge of ticketing, between MondoMostre, the exhibition’s organizing company, which “provides both the full service of financing, organizing and promoting the event, as well as a range of services such as ticketing, communication, promotion, creation of special evenings and sponsor search”? What percentages of the entire proceeds are to be donated to the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Abatellis? Is it always MondoMostre or the Scientific Management of Abatellis that sent the loan requests and decided on the admission fees? Tickets that, in light of the works’ absences, appear rather high in price: €13 full, €11 reduced, €11 groups, €13 weekend groups, with a pre-sale of €2 for groups and individuals.

|

| The photograph of the work that did not make it to the exhibition |

|

| The sign accompanying the photograph above |

|

| Left, the Annunciation on display (inside its case) at Palazzo Bellomo. Right, the work on display at the Palermo exhibition. |

These are legitimate questions, just as legitimate is knowing whether it was really worth uprooting theAnnunciation from its context from the Regional Gallery of Palazzo Bellomo in Syracuse, a work that has several conservation issues: damaged by the 1693 earthquake, it has suffered moisture and decay for centuries and in 1914 a tear of the paint film from its original wooden support to be glued on canvas. A work that at Palazzo Bellomo is placed inside a vitrine that maintains humidity and temperature indices and environmental microclimatic conditions unaltered. The work now on display at Abatellis is devoid of any protection and of any element that maintains stable environmental values, something that the Uffizi’s Polyptych with the Madonna and Child, St. John and St. Benedict presents instead, plausibly a constraint imposed by the Florentine museum and not adopted for the’Syracuse work, which, moreover, precisely for the reasons of its delicate status, is placed as a valuable work among the immovable assets “that constitute the main fund of Museums, Galleries, Libraries and Collections” according to Regional Council Resolution nos. 94 and 155 of 2013 by Assessoral Decree No. 1771 of June 27, 2013, along with the Abatellis’Annunciata and the San Gregorio Polyptych of Messina. There are prescriptions, albeit onerous, that must be guaranteed and enforced, elements and factors that are indispensable to ensure the safety of works of art: the handling of it from Palazzo Bellomo and its transport (as per video footage and journalistic documentation published on the web) probably did not benefit the work, its delicacy should have led to evaluations with more critical sense in order to avoid forcing and tensions between the glues and the support and the pictorial film. I do not resume the articles and the back-and-forth of statements between those who asserted the absolute scientific nature of the operation and of the necessary, almost obligatory, presence of the work and between those who, rightly, raised the questions of protection and preservation, elements that turned out to be well-founded.

Doing a quick count, of the fifteen works declaimed and publicized, the infamous “half of Antonello’s works,” four are missing from the roll call (i.e., the two from Reggio, the one from the Louvre and the National Gallery), while as many as four are from the Abatellis’ permanent collection(Annunciata and the three Doctors of the Church); the actual loans of Antonello’s works are only seven, in addition to these the panel Madonna and Child by Jacobello by Antonello from the Accademia Carrara in Bergamo.

In light of this reflection, a passage from Tomaso Montanari ’s pamphlet Against Exhibitions (Einaudi, 2017) seems illuminating and fitting: “Call them what you like: box office exhibitions, blockbuster exhibitions, all-inclusive exhibitions. The ingredients are always the same. Mostly the universally best-known and media-savvy masters are proposed. In most cases, generic, specious, superficial. Mediocre, picky, even useless, harmful and based on the exhibition of some ’trophy’ known by all, which is turned into idol void: into icon-symbol. Paintings that had once had the capacity to express precise meaning lose their semantic and symbolic depth: they are reduced to objects that can provide (at best) vague visual satisfaction. ”A nefarious epidemic,“ we might say, taking up an impassioned j’accuse by Cesare Brandi, We are besieged by [un’] infesting proliferation of exhibitions-events of little or no cultural value, devoted to an’ephemeral spectacularization as an end in itself, ’returnable empties’ that artificially induce fetishistic consumption, multicolored soap bubbles that leave behind practically nothing.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.