All the humanity of the poor by Giacomo Ceruti. What the Miseria&Nobiltà exhibition in Brescia looks like.

To think of eighteenth-century art, images of vast heavenly expanses, frivolous worldly amusements, large airy and terse halls, mirrors, gardens, wigs, feathers, and swings immediately come to mind. One tends to think less of an art that depicted the poor, an art of the last, the wretched, the slums, the dirty, smelly streets, populated with beggars, peasants, cobblers, spinners, pilgrims. These are the characters that recur in the art of Giacomo Ceruti, an exceptional painter who lived in early 18th-century Lombardy, a successful artist during his lifetime, forgotten when he died, rediscovered in the mid-20th century, and yet never quite able to escape from the little fortune he enjoys among the general public. His is an art of earth and dust, the exact counterbalance to that made of air and sky that usually populated the homes of the nobility. Although Ceruti’s paintings still managed to enter their dwellings. And this is one of the themes, if not the most engaging theme, of the major exhibition Brescia is dedicating to Ceruti: it is entitled Miseria & Nobiltà. Giacomo Ceruti in Eighteenth-Century Europe, and it has been set up at the Museo di Santa Giulia, in the year in which the city where the painter spent most of his life was given the honor of being the Italian Capital of Culture. The main objective of the three curators, Roberto D’Adda, Francesco Frangi and Alessandro Morandotti, is to make a complete reconnaissance of Ceruti’s art, also to show that Giacomo Ceruti was indeed a painter of the poor, but also something else: a portrait painter of boundless talent, a respectable naturamortist, a masterful director of sacred compositions (on the sacred Ceruti insists, moreover, a special exhibition, independent of the Santa Giulia one, that Angelo Loda curated at the Museo Diocesano in Brescia).

Giacomo Ceruti, then, and no longer “Pitocchetto,” that reductive nickname that has contributed to the artist’s fortunes since time immemorial. The theme of the painting of the last is nevertheless inescapable, partly because the exhibition itself is composed, for at least a good half, of his portraits of poor people begging for alms, his porters toiling under the weight of their baskets, his humble artisans busied in their daily activities, peasants caught in front of miserable meals. And in part because we still wonder not only why Ceruti’s production abounds with similar subjects, but also why he was able to be successful with a clientele that one can hardly imagine buying paintings like those on display in Brescia. Already Roberto Longhi had framed the problem: Ceruti’s poor are not “diminished and zeroed in within small telucce that the Rococo frame would have easily disguised as cheerful hall ornaments, but, dangerously, as large as the real thing, as large as the altar pictures in the churches of ancient religion once were, and painted with the same, ancient faith.” Here, then, Ceruti’s appearance returned “sociologically almost inexplicable in those days.” Of course, after Longhi the issue was better circumscribed: it was insisted, for example, that Ceruti was not an isolated case (seventeenth-century France had seen the Le Nain brothers, while in Italy the tradition of the poor as protagonists of works of art can be can be traced back to Caravaggio, but in Merisi’s case the revolution lies above all in having re-discussed the hierarchies of artistic genres), and on the fact that the apparently empathetic pathos of the Milanese can also be found, for example, in certain touching paintings by Georges de la Tour, although these are rather isolated events, while Ceruti’s continuity is a case in itself. The problem of trying to identify the origin of these paintings that seem to us so heartfelt, however, remains, and indeed widens: for the Le Nain brothers, for example, interpretations of a religious nature have been given (their proximity to the circles of the charitable institutions of mid-seventeenth-century Paris), for Ceruti the idea of a pre-Enlightenment sensibility has also been advanced. Hypotheses that at the moment, however, seem little viable.

One anticipation can already be given: the exhibition does not give a definitive answer to the problem. It is, however, one of the most exciting exhibitions recently seen in Italy (accompanied by an excellent catalog: difficult to find others as thorough and as enjoyable to read), and above all it is the first review on Ceruti to be organized since the 1987 exhibition, the first (and last) monographic exhibition dedicated to the artist, Milanese by origin but Brescian by adoption, curated by Mina Gregori, to whom we owe much of the rediscovery of this extraordinary painter, and who, five years earlier, published the first systematic study on him, at the height of a season that had begun with the studies by Roberto Longhi and had continued with those of Giovanni Testori, and would then see as further protagonists, starting in the 1980s, scholars such as the curators of the current exhibition, or like the art historian Francesco Porzio, who signed one of the essays in the catalog. Miseria & Nobiltà starts from there to put in place, reads the presentation by Morandotti, Frangi and D’Adda, a “necessary revision activity” that takes into account the research of the last thirty-five years: what has resulted is an itinerary divided into seven sections that reconstruct, in the light of the most up-to-date studies, Ceruti’s entire career, contextualized in his era, among his certain patrons, in a complete itinerary, where there is no lack of major works, and that despite its length proceeds at a brisk pace and arouses the desire to return.

The tour itinerary begins with the first chapter, dedicated to Ceruti’s twentieth-century rediscovery, and built around perhaps the Lombard painter’s most famous image, the Laundress that became part of the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo’s collection in 1914, a work that rekindled the spotlight on the artist since was exhibited at the exhibition on Italian painting of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries held in Florence in 1922, causing the painter to attract the attentions of critics and the beginning of the critical reconstruction of his story, with the first studies by Roberto Longhi. Accompanying La Lavandaia are, in fact, some works that figure among the first Cerutian “discoveries,” starting with the four canvases (the two “porters,” young boys assigned to the transport of baskets, and two interior scenes) exhibited at the 1953 exhibition of I pittori della realtà in Lombardia, fundamental for the critical arrangement of Giacomo Ceruti. In the same section we then observe the Portrait of a Young Woman with Fan first attributed to Ceruti by Roberto Longhi and never again questioned. It is precisely from portraiture that the journey into Ceruti’s art begins: the artist’s beginnings are under the banner of this genre, although we have no information on his training. However, the quality of his portraits suggests, with reasonable margins of certainty, that he had become familiar with portraits, since the first phase of his career, as Francesco Frangi explains, is “marked by a constant predilection for that artistic genre that can be reconstructed today through a series of testimonies certainly referable to those years.” The exhibition does not include what is supposed to be the first work that can be dated with certainty, the portrait of Giovanni Maria Fenaroli, but it is possible to admire some significant essays by Ceruti as a young portraitist, such as the Portrait of Abbot Angelo Lechi or the Portrait of a Capuchin Friar, both referable to the years of the artist’s documented stay in Brescia between 1721 and 1733, and both able to effectively embody the characters of Ceruti’s early portraiture: serious poses and gestures reduced to a minimum, earthy realism, somber backgrounds, in contrast to coeval international portraiture, the dominance of "the strictest understatement,“ as Francesco Frangi well explains, ”moreover seconded by the lowered tone of the coloristic register and the restrained poses of the characters."

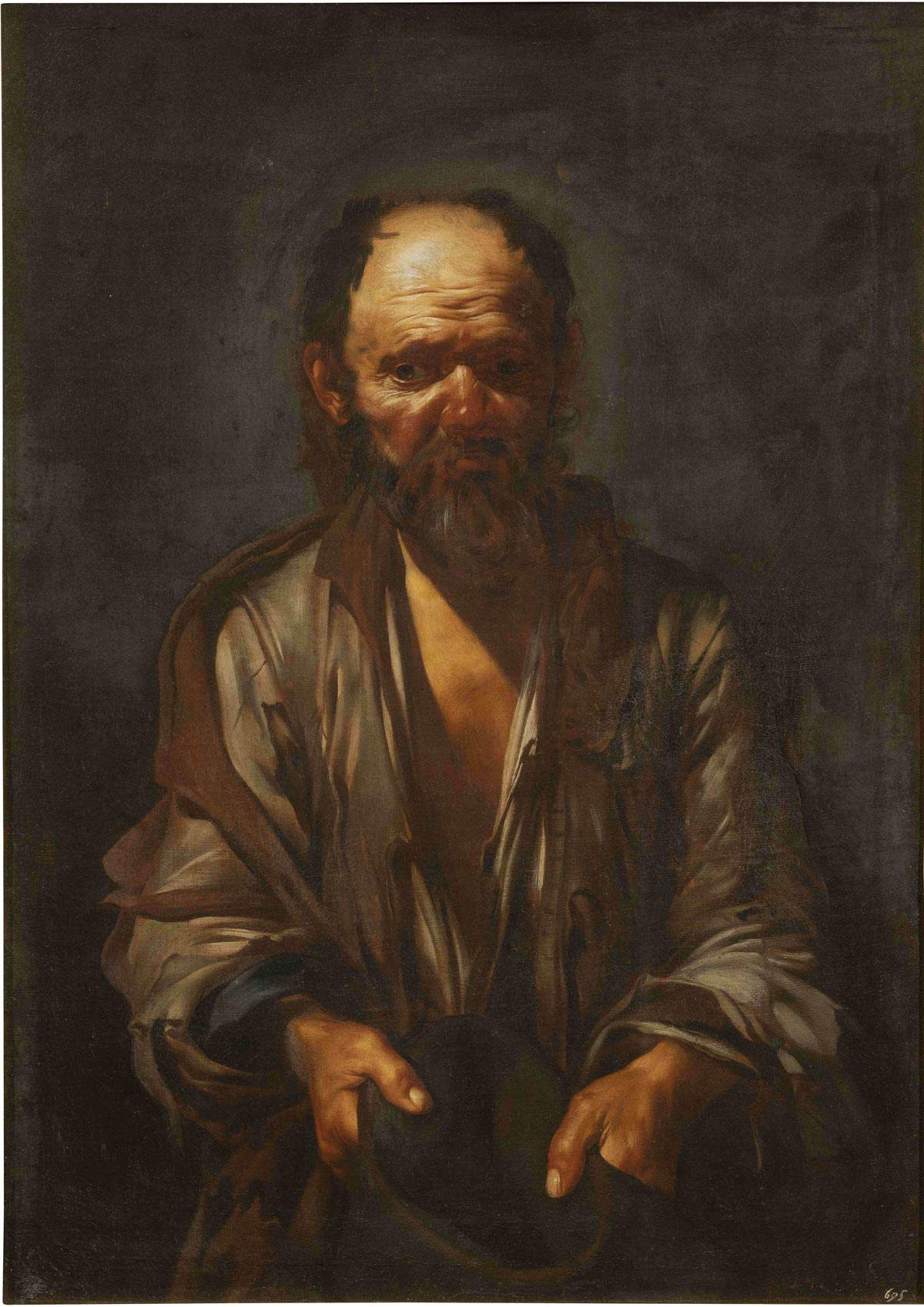

The most typical subjects of Cerutian production appear in the exhibition in the third section, The Scenes of Popular Life. Precedents and companions, which despite its title contains most of the paintings with which Ceruti’s art is most commonly associated, as well as illustrious precedents and painters who, at the time of the Milanese artist, practiced his same genre. It opens with a large, impressive canvas of Popolani in the open air, which is striking for the sullen, stern expression of his mother, who casts a fiery glance at the viewer, distracting herself for a moment from her paltry sewing work. The work, for which the critics have not yet been able to formulate with certainty the name of an author (in the past, that of Ceruti himself has also been proposed, an attribution that had a certain fortune counting among its supporters even Federico Zeri, until was contested by Mina Gregori, and even today it is still difficult to find a candidate that everyone agrees on), and which has at most been likened to the environment of Pietro Bellotti from Lake Garda (a painter, however, who is elusive and of whom few hours are known), summarizes the characters that will be characteristic of Ceruti’s art of the poor: commoners intent on their daily activities, but painted without macchietistic or satirical connotations, without moralistic intonations, without a desire to compose a pleasing or amusing genre scene, and captured with supreme dignity, almost as if we might think that the artist wanted to make himself somewhat of a participant, to manifest a spirit of solidarity, or that he wanted, if not to break down, at least to blunt the barriers between himself and his subjects. Pietro Bellotti is also present in the exhibition, with one of the most important works in his catalog, namely, the commoner elevated to a mythological figure (the Parca Lachesi of 1660-1665: a humble old woman becomes one of the three deities who unravel the thread of human existence). And the section on precedents is complemented by a Beggar by José de Ribera, to find in a specific strand of Caravaggism one of the origins of Ceruti’s painting (the work, Morandotti explains, “is a touching image in its brutal truth and restores well to us the idea that it is only from Caravaggio and his close circle that artistic researches interpreted heartfeltly the social reality, even the humblest”), from some of the common people of Michel Sweerts, a Flemish painter responsible for the diffusion of a vast repertoire of pitocchi figures presented without the slightest derisive intent, to then continue with an artist such as the Master of the Denim Cloth (because of the recurring use of characters dressed in garments made of this fabric), author of “moving popular scenes whose ancient fortune is documented early fortune in Lombardy” (so Morandotti), passing through a scene of Players of Bowls, possibly the work of a Slovenian painter whose nickname we know only (Almanach), interesting in that it is believed, because of the composed truth with which the scene is described, to be one of the most immediate precedents for the paintings of Ceruti’s Padernello cycle (which the visitor sees in the section immediately following), to come to another artist of the generation that preceded Ceruti’s, namely Giacomo Cipper known as the Todeschini, who is present with an Old Spinner and Boy Eating.

The same room, as anticipated, brings together several of Ceruti’s works, intermixed with those of context artists: next to Bellotti’s Parca Lachesi, for example, the public will find one of the most intense paintings in the entire exhibition, the Beggar from the Konstmuseum in Gothenburg, a realistic and moving portrait of an old man dressed in rags, who implores us with his gaze and stretches his hat toward us with his hand. The beggar begging, Paolo Vanoli explains in the catalog, “is a leitmotif of painting on pauperistic subjects in the Lombard area between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the roots of which are to be found in the sampler of motifs and situations codified in the etchings of Jacques Callot - well known also to Ceruti - dedicated to the representation of the poor and marginalized,” yet rarely, even in Ceruti’s own painting, do we achieve such exciting and engaging results. It is paintings like these that question us about the motivations that led Ceruti to paint characters like his Beggar, and his customers to buy them. A common trait of Ceruti’s poor is their great dignity: there is never a thread of shame, nor of self-pity, much less of sass in their looks, in their poses. Even without attaining the sentimentality of the Gothenburg painting, certain paintings (such as the recently discovered private collection Beggar, or the Moorish Beggar, or even the Peasant leaning on a spade) stand out for their austere, almost magniloquent approach, capable of achieving, especially in the Moorish B eggar and the Peasant leaning on a spade, an unusual monumentality: the room paneling rightly speaks of “popular epic,” and paintings like these fully restore the sense of it. Completing the room are the two nonchalant porters from the Pinacoteca di Brera, caught in an “unforgettable still image, thanks to which Ceruti restores life to two monumental figures on the margins of society, yet worthy of an ennobling portrait,” as Morandotti points out, and the Two Pitocchi caught playing cards around a bench used as a small table: Ceruti lingers on the expressions of the two characters, stern the one of the poor man on the left bundled up in a long military coat (perhaps the character had been a soldier) and holding a tender kitten in his hands (an animal that could, however, allude to the character’s furfantish nature, since in ancient times the cat had negative symbolic connotations), and inebriated the one of the character on the right.

Giacomo Ceruti,

Giacomo Ceruti,

Giacomo Ceruti,

Giacomo Ceruti,

The next section displays almost the entirety of the so-called Padernello “cycle,” which cycle it may not actually be: the name is due to the fact that the works (one of which is signed) appear homogeneous in style and subject matter, and they were all found in the same place, but it is not certain that they were intended as canvases to be exhibited all together. The discovery, which dates back to 1931, was due to art historian Giuseppe De Logu, who that year discovered the existence of thirteen paintings with subjects of popular life that were kept at the castle of Padernello, in the lower Brescia area. With subsequent research, it was possible to juxtapose three more works with the cycle: a total of fourteen can be seen at the Brescia exhibition. We do not know their early history, nor do we know who the patrons were (we only know that at some point in their history they found themselves passing through the properties of the Fenaroli, one of the most important Brescian families, and we know that at least three of the paintings were made for another local family, the Avogadros). Stopping in front of the canvases of the Padernello cycle is tantamount to making a descent among the commoners of eighteenth-century Brescia, whom Ceruti, also on the strength of his stylistic maturity (the works have been dated to shortly before his move to the Veneto, which began in 1733), captures in their activities daily activities, restoring them with a less set realism, less severe and even less touching than that of the works seen in the previous room, but certainly more frank, brighter and with more cursive tones. There is no shortage of works with a portraiture bent (the Dwarf, for example, or the Porter with a Dog), but most of the canvases focus on weekday moments: so here is a brawl between porters, a spinner intent on her work who is approached by a small beggar woman who tends her saucer, or again two innkeepers who are busy tapping wine, a group of girls taking sewing lessons. This is the last time in the exhibition we get to appreciate such a harshly realistic Ceruti: from here on, his art will become decidedly lighter, elegant, in some ways even sophisticated.

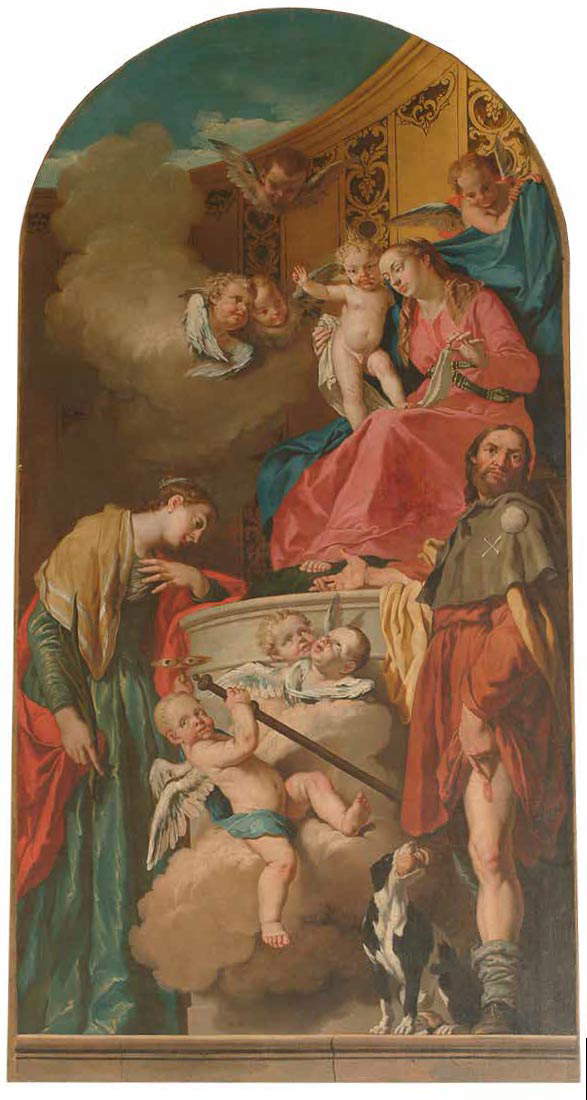

This stylistic shift is immediately apparent in the next section, dedicated to Ceruti’s stay in the Veneto: we find the artist first in some towns in the Bergamo area, and then, starting in 1735, in Venice, where he worked for Field Marshal Johann Matthias von der Schulenburg, appointed in 1715 commander-in-chief of the Serenissima’s land forces, and a passionate and refined collector of contemporary art. Schulenburg did not disdain paintings with subjects typical of Ceruti’s early production: at Santa Giulia one can thus admire the Three Pitochos on loan from the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid and identifiable with the “painting of the three Pitochos” mentioned in the inventories of the field marshal, a painting that “shows itself distinguished by a more meticulous and refined naturalism than the essential and standoffish approach that qualifies the pauperist interpretations made by theartist during the third decade of the 18th century” (thus Francesco Ceretti), due to a more studied lighting, to a greater refinement in the expressions of the characters who lose a little of the naturalness of Padernello’s figures in the direction of a more calibrated composition, more constructed, set so that the cross-references between the gazes of the characters give an almost lyrical connotation to the scene. And to get a glimpse of Cerutian luminism, one need only look at the two still lifes, also once in Schulenburg’s collection, displayed next to the Three Pythons: works with a Nordic flavor, they are striking for their apparent nonchalance when in fact they are paintings in which Ceruti’s natural propensity for realism is mixed with a compositional refinement that probably touches one of the pinnacles of his production (one need only look at the care with which the carrots in the privately collected canvas are arranged, placed next to the lobster’s claws because they recall their shape and size, or the chestnuts in the Kassel painting: they seem to be there by chance, but we can imagine the painter trying to place them one by one to fill an empty space while balancing, moreover, their tones with those of the hare’s innards). The section on the Venetian Ceruti is completed by one of his altarpieces, the Madonna with Saints Lucia and Rocco executed for the church of Santa Lucia in Padua, and placed in dialogue with one of the most direct references, the Madonna and Child with Saint Charles Borromeo painted for Santa Maria della Pace in Brescia by Giovanni Battista Pittoni, a Venetian artist but very active in the Mainland: Ceruti’s altarpiece, set on the diagonal cut inaugurated two centuries earlier by Titian (the same as Pittoni’s altarpiece to which Ceruti refers), is his only painting of a sacred subject in the exhibition, but it is a painting of very high quality that is well able to testify to the level that the artist was able to reach even in this genre.

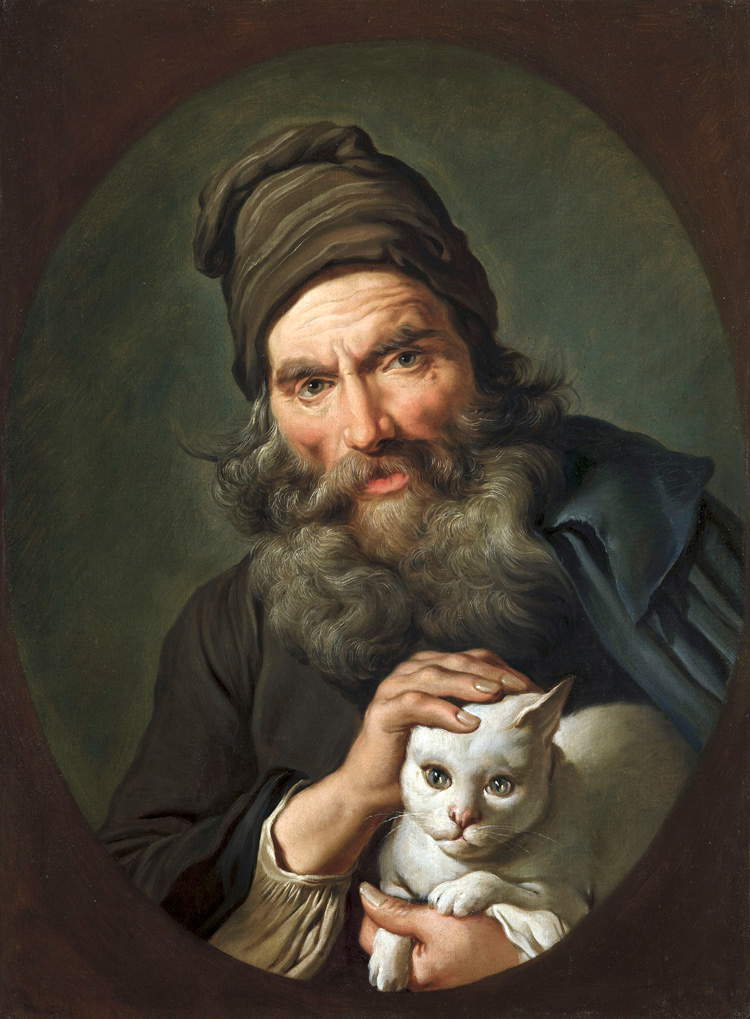

The section on mature portraiture shows a different Ceruti from his youthful trials: the portraits from the 1930s onwards certainly appear more rhetorical, more set, closer to international taste. Examples of this are the Portrait of a Young Gentleman at the Pinacoteca Tosio Martinengo, and perhaps even more so the Portrait of a Young Amazon Woman at the Fondazione Trivulzio, “institutional” portraits, one might say, that are certainly more similar to those of a Hyacinthe Rigaud, i.e., one of the portrait painters most in demand by the European ruling classes of the early 18th century (on display is his splendid Portrait of Anton Julius II Brignole Sale, lent by the National Gallery of Palazzo Spinola in Genoa). Closing the exhibition entrusted to the genre scenes of the last phase of Giacomo Ceruti’s career, completely different, however, from those of his early activity, or of the Padernello cycle: the distance, Francesco Frangi explains, lies above all in the fact that "the representations of popular themes become progressively more elegant and disengaged, their protagonists are almost always dressed in humble but decent clothes, sometimes smiling explicitly. The poor almost completely disappear from his art: there remain certain posed workers, such as the Boy with Basket of Fish and Spider Crab, who smiles aware of being captured by the artist, or like the spinner and the shepherd in the large painting of the Castello Sforzesco, also almost paluded (were it not for the ironic insertion of the cow caught while bellowing, or that of the dog sleeping in the foreground, it would almost have the air of an official portrait). The most likely explanation is that this final turn by Ceruti responded to changes in taste and orientations on the part of the patrons. His figures, however, do not lose the realism that had always distinguished them: it is enough to observe in this regard the exactness and acumen of the Old Man with Dog and the Old Man with Cat, with the two characters who retain in their eyes all the naturalness of the early Ceruti (and it might seem strange to us that in the ancient inventories they were recorded as figures “of Bernesque style,” that is, comic figures: at the time they were perceived as such). To find some evidence of the ancient spontaneity we need to dwell on the last work in the exhibition, the Evening on the Square, the result of a commission (one of the last for paintings of the pauperistic genre) from the Marquis Busseti of Avolasca for the decoration of a room in their palace in Tortona. Even if the composition is the result of meditations and borrowings from assorted engravings (a modus operandi typical of Ceruti, who takes several motifs, for example, from Jacques Callot: a small exhibition, again in Santa Giulia as an appendix, displays the prints from which the details of Ceruti’s works are taken), the artist still manages to produce a credible scene, one of the last flashes of a painter who spent most of his life painting the humble.

Giacomo Ceruti,

Giacomo Ceruti, Giacomo Ceruti,

Giacomo Ceruti,

Giacomo Ceruti,

Giacomo Ceruti, Giacomo Ceruti,

Giacomo Ceruti,

One therefore leaves with the same question as when one entered: for whom did Giacomo Ceruti paint? Why so much apparent sharing in his scenes of life on the margins of society? The question is a complex one. At first glance, one might assume that Ceruti felt sincerely about the subjects of his works. His poor, especially those of his younger years, appear so alive, so real, so believable, so dignified that we might think Ceruti wanted to express some sort of empathy toward them. To bring the problem into better focus, however, it is necessary, first of all, to widen our gaze: the experience of Giacomo Ceruti, however original in the context of the Lombard arts of the 18th century (but one could also safely speak of Italian and European arts), was not isolated. It became apparent, even as we walked through the rooms of the exhibition, that there was a large number of specialists, more or less well-known, more or less successful, who tried their hand at the same genre, a sign that there must have been an equally large collector base, at least between Lombardy and the Veneto, who asked painters for paintings with scenes of popular life. There are documented cases of collectors asking Ceruti’s colleagues for entire cycles with scenes of everyday life of the humble: a fashion had set in, one might say. A fashion whose roots lay in seventeenth-century art. It is therefore not strange that Ceruti painted commoners. There is, however, a substantial difference that separates Ceruti from the others: Morandotti, in comparing the Lombard to Cipper, rightly points out the “relevant gap in terms of poetic intensity and empathetic approach to the subjects” that clearly divides the two artists, to the point of risking “obscuring the often very close relations that run between the works of the two artists, on the front of both thematic choices and certain compositional solutions.” Ceruti’s originality lies in the way the artist approached his characters: the same intensity that the artist poured into his portraits is to be found in his porters, his poor, his beggars. “In Ceruti’s youthful canvases,” Morandotti again points out, “everything suddenly becomes serious.” And at the moment when the conditions of the poor become an element of serious reflection, Ceruti’s art seems to us to become almost subversive: hence the reason for the adverb “dangerously” used by Longhi.

There is to be considered, however, at the same time, that measuring paintings produced by an artist three centuries ago with the yardstick of the 2000s is an equally dangerous exercise. In other words: today we observe, for example, the beggar in the Konstmuseum in Gothenburg, and we feel compassion. Much more than by observing, for example, Ribera’s beggar, who emerges from a gloomy background, does not thrust his eyes into ours as Ceruti’s does, has his face partially in shadow: there are still elements that make us uncomfortable. For Ceruti’s is not so: we would feel like helping him, to have a word with him, to stretch something out to him. Or anyway, even if we wanted to keep our distance, that look touches us deeply. But was it like that even in Ceruti’s time? Was this feeling of compassion really so dominant that the Lombard painter became a rebel, an extremist?

It is a matter of times and codes, as Francesco Porzio warns: “while today Ceruti’s pitocchi solicit a protective reaction, back then they were perceived as types from a distant and curious world, and more often as negative types. A century before Courbet, naturalism did not radiate a democratic aura; it was still in the service of satire and ridicule.” It is true that Ceruti’s subjects are neither satirical nor ridiculous, but in his time their presence was enough to suggest an unbridgeable distance. It was enough for a work to depict a poor person, an outcast, to arouse disapproval, hilarity, amusement. It sounds cruel to us today, but the taste for scenes of popular life did not establish itself because there was compassion for the subjects depicted: it established itself because they were decorative, because they were thought to be pleasing, because often the genre scenes did not even lose their moralising intentions, and sometimes continued to make people laugh. And as seen above, Ceruti’s works are not even to be understood as photographs, given the fact that they were often constructed from engravings or ideas gathered from the productions of other artists. The idea that they might express social solidarity, Francesco Porzio rightly cuts to the quick, is anti-historical. These observations, however, risk failing to answer the underlying question: why so much humanity in Ceruti’s subjects? There is no certain answer, let alone an unambiguous answer. We do not know Ceruti’s intentions, and any ideological reading, however fascinating, runs the risk of misrepresenting the content of his paintings. It is plausible, for the writer, that the humanity of Ceruti’s subjects was a formal device. A way to make his subjects more authentic and sincere than those of his contemporaries. And thus a way to distinguish himself, a way to seek an originality actually found only in his production. In a market where artists abounded who were perfectly capable of offering buyers realistic paintings like Ceruti’s (think of Bellotti alone), the Milanese had invented a sort of trademark. Completely abandoned when tastes turned elsewhere. From an artist moved by genuine sensitivity to his subjects one would expect continuity: at the current state of research we know that instead, after the mid-thirties, the return to that painting would become very sporadic. Or was it a matter of a change of ideas on Ceruti’s part? Such a sudden abandonment and the coincidence with the different directions of artistic trends could lead us to answer this question in the negative. Of course, today it would be nicer to think of a Ceruti anticipating the Enlightenment, a painter who rebukes his wealthy patrons for situations that on the street they turn away from or do not even want to see, and instead appreciate on canvas. In the absence of news about the artist’s ideas, however, it is better to be cautious: exhibitions should also serve to demythologize. It means that they have done their work well. Miseria & Nobility is therefore also a very useful exhibition for understanding the picture of pauperistic art in the 18th century. Besides being one of the best Italian exhibitions in recent years.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.